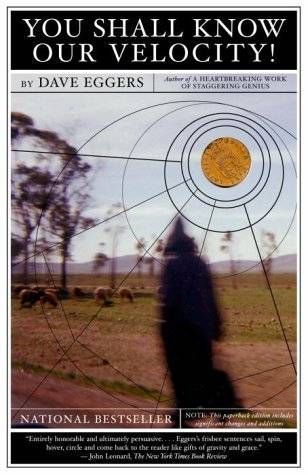

"You Shall Know Our Velocity" - читать интересную книгу автора (Eggers Dave)

|

Dave Eggers

You Shall Know Our Velocity

Thank you Flagg, Marnie, Sam, Jenny, Chris, Brie, John, Cressida, Andrew, Michael and Eli

Thank you Sarah, Barb, Julie, Scott, Yosh and everyone at McSwys and 826 Valencia

Thank you Toph and Bill

This book owes a tremendous amount to Brent Hoff

Everything within takes place after Jack died, and before my mom and I drowned in a burning ferry in the cool tannin-tinted Guaviare River, in east-central Columbia, with forty-two locals we hadn't yet met. It was a clear and eyeblue day, that day, as was the first day of this story, a few years ago in January, on Chicago's north side, in the opulent shadow of Wrigley and with the wind coming low and searching off the jagged half-frozen lake. I was inside, very warm, walking from door to door.

I was talking to Hand, one of my two best friends, the one still alive, and we were planning to leave. At this point there were good days, good weeks, when we pretended that it was acceptable that Jack had lived at all, that his life had been, in its truncated way, complete. This wasn't one of those days. I was pacing and Hand knew I was pacing and knew what it meant. I paced like this when figuring or planning, and rolled my knuckles, and snapped my fingers softly and without rhythm, and walked from the western edge of the apartment, where I would lock and unlock the front door, and then east, to the back deck's glass sliding door, which I opened quickly, thrust my head through and shut again. Hand could hear the quiet roar of the door moving back and forth on its rail, but said nothing. The air was arctic and it was Friday afternoon and I was home, in the new blue flannel pajama pants I wore most days then, indoors or out. A stupid and nervous bird the color of feces fluttered to the feeder over the deck and ate the ugly mixed seeds I'd put in there for no reason and lately regretted – these birds would die in days and I didn't want to watch their flight or demise. This building warmed itself without regularity or equitable distribution to its corners, and my apartment, on the rear left upper edge, got its heat rarely and in bursts. Jack was twenty-six and died five months before and now Hand and I would leave for a while. I had my ass beaten two weeks ago by three shadows in a storage unit in Oconomowoc – it had nothing to do with Jack or anything else, really, or maybe it did, maybe it was distantly Jack's fault and immediately Hand's – and we had to leave for a while. I had scabs on my face and back and a rough pear-shaped bump on the crown of my head and I had this money that had to be disseminated and so Hand and I would leave. My head was a condemned church with a ceiling of bats but I swung from this dark mood to euphoria when I thought about leaving.

"When?" said Hand.

"A week from now," I said.

"The seventeenth?"

"Right."

"This seventeenth."

"Right."

"Jesus."

"Can you get the week off?"

"I don't know," Hand asked. "Can I ask a dumb question?"

"What?"

"Why not this summer?"

"Because."

"Or next fall?"

"Come on."

"What?"

"I'll pay for it if we go now," I said. I knew Hand would say yes because for five months we hadn't said no. There had been some difficult requests but we hadn't said no.

"And you owe me," I added.

"What? For – Oh Jesus. Fine."

"Good."

"For how long again?" he asked.

"How long can you get off?" I asked.

"Probably a week." I knew he would do it. Hand would have quit his job if they refused the time off. He had a decent arrangement now, as a security supervisor on a casino on the river under the Arch, but for a while, in high school, he'd been the Number Two-ranked swimmer in all of Wisconsin, and he expected that kind of glory going forward. He'd never focused again like he'd focused then, and now he was a dabbler, with some experience as a recording engineer, some in car alarms, some in weather futures (true, long story), some as a carpenter – we'd actually worked on one summer gig together, a porch on an enormous place – a gingerbread-looking place on Lake Geneva – but he left any job where he wasn't learning or when his dignity was anywhere compromised. Or so he claimed.

"Then a week," I said. "We'll do what we can in a week."

I lived in Chicago, Hand in St. Louis, though we were both from Milwaukee, or just outside. We were born there, three months apart, and our dads bowled together, before mine was gone the first time, before his started playing drums and wearing leather vests. We didn't talk about our fathers.

We called the airlines that offered single-fare tickets with unlimited travel. The tickets allowed unrestricted flying as long as you kept going one direction, once around the globe without turning back. You usually have twelve months to complete the circuit, but we'd have to do it in a week. They cost $3,000 each, a number out of the reach of people like us under normal circumstances, in rational times, but I had gotten some money about a year before, in a windfall kind of way, and had been both grateful and constantly confused by it. My confusion knew no limits. And now I would get rid of it, or most of it, and believed purging would provide clarity, and that doing this in a quick global flurry would make it – I actually don't know why we combined these two ideas. We just figured we would go all the way around, once, in a week, starting in Chicago, ideally hitting Saskatchewan first, then Mongolia, then Yemen, then Rwanda, then Madagascar – maybe those last two switched around – then Siberia, then Greenland, then home.

"This'll be good," said Hand.

"It will," I said.

"How much are we getting rid of again?"

"I think $38,000."

"Is that including the tickets?"

"Yeah."

"So we're actually giving away what – $32,000?"

"Something like that," I said.

"How are you going to bring it? Cash?"

"Traveler's checks."

"And then we give it to who?" he asked.

"I don't know yet. I think it'll be obvious when we get there."

And if we kept traveling west, we'd lose very little time. We could easily make our way around the world in a week, with maybe five stops along the way – the hours elapsed would in part be voided by the crossing, always westerly, of time zones. From Saskatchewan we'd get to Mongolia, we figured, having lost only two or three hours riding the Arctic Circle. We would oppose the turning of the planet and refuse the setting of the sun.

The itinerary changed on each of the four days we had to decide, on the phone, with me consulting a laminated pocket atlas and Hand in St. Louis with his globe, a huge thing, the size of a beach ball, which spun wildly between poles – he'd bumped into it one late night and it was no longer smooth – and which dominated his living room.

So first:

Chicago to Saskatchewan to Mongolia

Mongolia to Qatar

Qatar to Yemen

Yemen to Madagascar

Madagascar to Rwanda

Rwanda to San Francisco to Chicago.

We liked that one. But it was too warm, too concentrated in one latitude. The next one, with adjustments:

Chicago to San Francisco to Mongolia

Mongolia to Yemen

Yemen to Madagascar

Madagascar to Greenland

Greenland to Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan to San Francisco to Chicago.

We'd solved the warmth problem, but went too far the other way. We needed better contrast, more back and forth, more up and down, while always heading west. The third itinerary:

Chicago to San Francisco to Micronesia

Micronesia to Mongolia

Mongolia to Madagascar

Madagascar to Rwanda

Rwanda to Greenland

Greenland to San Francisco to Chicago.

That one had everything. Political intrigue, a climactical buffet. We began, separately at home, plugging the locations into various websites listing fares and timetables.

Hand called.

"What?"

"We're fucked."

There was something wrong with the timetable. He'd entered in the destinations, but every time we left San Francisco – we had to stop there en route from Chicago – we'd end up in Mongolia not a few hours later, but two

"How can that be?"

"I figured it out," Hand said.

"What?"

"You know what it is?"

"What?"

"I'm going to lay it on you."

"Tell me."

"Ready?"

"Fuck yourself."

"The international date line," he said.

"No."

"Yes."

"The international date line!"

"Yes."

"Fuck the international date line!" I said.

"Can we do that?" he asked.

"I don't know. How does it work again?"

"Well, New Zealand is the farthest point, time-wise, in the world. They see the new year first. Which means that if we're traveling west from Chicago, we're doing pretty well in terms of saving time all the way until New Zealand. But once we get past there, we're a day ahead.

"We lose a whole day."

"If we leave Wednesday, we land Friday."

"So it won't help to be going west," I said.

"Not much. Not at all, really."

We called an airline representative. She thought we were assholes. If we wanted to get around the world in a week, she said, we'd be in the air seventy percent of the trip. Even if we followed the sun, we'd still be hemorrhaging hours all over the Pacific. "We have to go east," said Hand. "Maybe we go east, then west," I said.

"We can't. We have to keep going the same direction to get the fare."

The next itinerary:

Chicago to New York to Greenland

Greenland to Rwanda

Rwanda to Madagascar

Madagascar to Mongolia

Mongolia to Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan to New York to Chicago.

"But we're losing time each flight," I said. "Each flight is basically double the time this way."

"Hell. You're right."

"We have to drop the destinations down to four maybe. Or make them shorter."

"This blows," Hand said. "We have a whole week and we have to drop Mongolia. These planes are too fucking slow. When did planes get so slow?"

Next:

Chicago to New York to Greenland

Greenland to Rwanda

Rwanda to Madagascar

Madagascar to Qatar

Qatar to Yemen

Yemen to Los Angeles to Chicago.

But there were no flights from Greenland to Rwanda. Or Rwanda to Madagascar.

"Bullshit," I said.

"I know, I know."

Or Madagascar to Qatar. There was one from Saskatchewan to New York. And one from Mongolia to Saskatchewan. But nothing from Greenland to Rwanda. We were bent. Why wouldn't there be a flight from Greenland to Rwanda? Almost everything, even Rwanda to Madagascar, had to go through some place like Paris or London. We didn't want to be in Paris or London. Or Beijing, which is where they wanted us to stop en route to Mongolia.

"This is like the Middle Ages," Hand said.

"I had no idea," I said.

We had to scale back again. We started over.

"Let's just go," said Hand. "We get the big ticket and then make it up as we go. We don't have to plan it all out."

"Good," I said.

But no. The airline insisted on knowing the exact airports we'd visit along the way. We didn't need to provide precise dates or times, but they needed the destinations so they could calculate the taxes.

"The taxes?" Hand said.

"I didn't know they could do that."

We decided to skip the pre-planned round-the-world tickets. We'd start in Mongolia and just go from there. We'd land and then just hit the airports when we were ready to leave. Or better yet, we'd land, and while still at the airport, get our tickets out. The new plan felt good – it was more in keeping with the overall idea, anyway – that of unmitigated movement, of serving any or maybe every impulse. Once in Mongolia, we'd see what was flying out and go. It couldn't cost all that much more, we figured. How much could it cost? We had no idea. All I needed was to get around the world in a week, get to Mongolia at some point, and be in Mexico City in eight days, for a wedding – Jeff, a friend of ours from high school, was marrying Lupe, who only Jeff called Guad, whose family lived in Cuernevaca. Huge wedding, I was told.

"You were invited?" Hand said.

"You weren't?" I said.

I don't know why Hand wasn't invited. Could I bring him? Probably not. We'd done that once before, at another friend's wedding, in Columbus – we figured maybe they just didn't have his address – and only once we arrived did we realize why Hand hadn't been given the nod in the first place. Hand was blond and tall and dark-eyed, I guess you'd say doe-eyed, was well-liked by women and for better and worse had a ceaseless curiosity that swung its net liberally over everything from science to even the most sensitive and trusting women. So he'd slept with too many people, including the bride's sister Sheila, soft-shouldered and romantic – and it hadn't ended well, and Hand, being Hand, had forgotten it all, the connection between Sheila and the bride and so it was awkward, that wedding, so awkward and wrong. It was my fault, then and as it always is, in some uncanny way, every time Hand's combination of lust – for women, for arcana and conspiracy and space travel, for the world at large – and plain raw animal stupidity brings us, inevitably, in the path of harm and ruin.

But did we really have to get around the world? We decided that we didn't. We'd see what we could see in six, six and a half days, and then go home. We didn't know yet where exactly to start – we were leaning toward Qatar – but Hand knew where to end.

"Cairo," he said, sending the second syllable through a thin long tunnel of breath, the

"Why?"

"We finish the trip on the top of Cheops," he said.

"They still let you climb the pyramids?"

"We bribe a guard early in the morning or at sunset. I read about this. Everyone in Giza is bribable."

"Okay," I said. "That's it then. We end at the pyramids."

"Oh man," Hand said, almost in a whisper. "I always wanted to go to Cheops. I can't believe it."

I called Cathy Wambat, my mom's high school friend, a travel agent with a name that spawned a hundred crank calls. They'd been raised in Colorado, she and my mom, in Fort Collins, which I'd never seen but always pictured with the actual fort, hewn from area lumber and still walling the pioneers from the natives. Now Cathy Wambat lived in Hawaii, where apparently all the travel agents who matter now lived. After hearing the plan, she thought we were assholes too, though in a cheerful way, and made the reservations – two one-way flights from Cairo, Hand's continuing from New York to St. Louis and mine to Mexico City.

We had to figure out where to start. Hand called again.

"We're idiots."

"What?"

"Visas," he said.

"Oh."

"Visas," he said again, now with venom.

"Fuck."

Half the destinations were thrown out. Saskatchewan was fine but Rwanda and Yemen wanted them. What was the difference between a passport and a visa? I didn't know exactly but knew there was a wait involved – three days, a week – and this was time we didn't have. Mongolia needed a visa. Qatar, in a ludicrous show of hubris for a country the shape and size of a thumb, wanted a visa that would take a week to process. We were only three days away from the time Hand had taken off work.

He called again. "Greenland doesn't want a visa."

"Okay," I said. "That's where we start."

The tickets were deadly cheap, about $400 each from O'Hare. Winter rates, said the GreenlandAir woman. We signed on and got ready. Hand would drive up from St. Louis Friday and we'd leave Sunday, for a city that we couldn't find in a dictionary or atlas. The flight stopped first in Ottawa, then at Iqaluit – on Baffin Island – before landing at Kangerlussuaq sometime around midnight. We agreed to limit the bags to one each – nothing checked, nothing awaited or lost. We'd both bring small backpacks – not backpacker backpacks, just standard ones, meant for books and beach towels.

"Coats?" asked Hand.

"No," I said. "Layers."

The cold in Chicago that January was three-dimensional, alive, predatory, so we'd head to the airport in everything we were bringing. We'd pack cheap disposable clothes so if we ever made it to Madagascar we could just dump the heavier stuff there. Then up to Cairo in T-shirts and empty bags.

"Okay," said Hand. "You sure you want to pay for all this?"

"Yes. I need it gone."

"You're sure."

"I am."

"Because I don't want you doing this because of some weird purging bullshit thing. This doesn't have anything to do with anything -"

"No."

"Good."

"See you tomorrow."

I hung up the phone, jubilant, and threw myself into a wall, then pretended to be getting electrocuted. I do this when I'm very happy.

On Saturday I had to babysit my cousin Jerry's twins, Mo and Thor, eight-year-old girls. Jerry was the only relative I had in Chicago. My mom had left Colorado to marry my father, leaving her parents, now dead, and three sisters and four brothers, all of whom stayed in or around Fort Collins. And now that Tommy – my six-years-older brother, with his own garage and mustache – was grown, my mom had moved to Memphis, to be near some old friends and take classes in anthropology. Jerry, my Aunt Terry's son, the third of five, was the family's first lawyer, with his picture in the yellow pages, and had married Melora, whose severity – she spoke only in hisses – was confounded by her small frame, that of a fourteen-year-old boy.

Jerry and Melora knew I was pretty much always around and available, so I got the nod and Hand and I brought Mo and Thor with us to get clothes and sundries. Jerry's delicate wife hated my names for her girls but I wasn't about to call two eight year-olds, hyper kids who talked a lot, who liked to run ahead on the sidewalks and didn't mind being thrown around, goddamned Persephone and Penelope.

They were dropped off, with a honk from Melora. We met them at the door to my building. They'd met Hand three times before but didn't remember him.

"You don't look as bad," Mo said to me, her puffy pink coat swallowing her. I pulled the zipper down a few inches and she exhaled.

"It's getting better," I said.

"Now your eyes are blue," Thor added, though my eyes were always brown and were still brown. She stepped toward me and I knelt before her. "And this is new," she said, touching my nose, the red crooked stripe running down the bone.

"That was already there, idiot!" Mo said.

"Was not," Thor said.

"It was there," I said, trying to settle things, "but it's darker now. You're both right."

We walked to a nouveau-outdoors store humid with nylon and velcro, energy bars and carabiners and a climbing wall no one used. Hand and I needed pants, pants to end all pants – warm and cool, breathing and trapping in, full of pockets. I got a standard pair of khakis, though with multiple pockets – the safari-photographer kind with the big rectangular compartments with zippers and velcro, two on each leg. Hand burst from the dressing room loudly swishing – his pants were wide, shiny and synthetic, in a grey that looked silver.

"You look like a jogger," I said.

"They're comfortable," he said.

"Like a jogger with a dump in his pants!" Mo said.

"Yeah," Hand said, soaking his thumb in saliva and jamming it in Mo's ear, "but I feel

The twins ran free and everything in the store looked essential. A tiny lightweight flashlight to attach to a keychain. Beef jerky. A first-aid kit. Secret pouches for money and passports. Bandannas. Mini-fans. Insect repellent. I avoided eyes, tried to save everyone the trouble of seeing me. My face wasn't as bad as it had been a few weeks ago, but it was still busted in places, and the bridge of my nose dropped blue shadows into my eye sockets, lending me a crosseyed or cycloptic look. I appeared as I was: a guy who'd been given an ass whipping by three guys in a steel box.

"You're limping still," Hand said.

"Yes," I said.

"It's not that bad," he said. "Just a little creepy is all."

Hand had ten bandannas, five for each of us. Bandannas, he said, were what every traveler came back wishing they'd had more of. "You'll thank me," he said. He said this a lot,

Mo and Thor returned from their explorations, hair matted, sweaters tied around their waists. They wanted to leave.

"Who wants to leave?" I asked Thor. "You, Mo?"

"I'm Thor," Thor said.

"Who's Thor?" I asked.

"I am!" she said.

"I'm sorry," I said. "I can't tell you people apart."

"But we're fraternal twins!" she said.

"You're what?"

Mo rolled her eyes. "Fraternal twins! You know that, stupid."

I stroked my chin, thinking. "Well, I guess I had heard something about this, but I didn't think it was true. I guess I didn't want to believe it."

"What are you talking about?" said Mo. She was so easily annoyed, her face pinched like the tip of a tomato.

"Listen," I said, crouching down in front of them both. "Do me a favor. Don't let anyone tell you there's something wrong with you. Don't let any scientists or government researchers pull you aside and make you feel like freaks just because you're twins and you don't look alike. God made a mistake, and yes it was a very big one, because what kinds of twins don't look alike? And worse, what kind of twins look like you two, like monkeys dunked in acid -"

Thor slapped me square in the forehead.

"You were talking too fast," she said.

We took them to Walgreen's. We needed provisions for the trip. The truth is, they were easily the least identical twins I'd ever seen, and only Thor looked like the product of their parents, who were both blond and fair. Thor was Aryan and thin-boned, but Mo looked more like me, with dark straight hair, dark eyes, long black lashes. I have the sort of eyelashes, black and shaped like bats' wings, that imply I'm wearing eyeliner, and the good fortune this has occasionally wrought is nothing compared to the grief, the stares, the constant Robert Smith comparisons. Mo has been mistaken for my own kid and hates this.

I bought travel-sized toothpaste and a collapsible cup, sunglasses and two $7 sweatshirts, maroon and black. Hand had a large column of deodorant and we were at the cash register, waiting for the girls and watching the woman ahead of us assemble a small stack of coupons on the counter. Each coupon had been cut with care and the woman, tiny but with a wide purple burn scar on her thin fragile neck, had them all bundled within a wide plastic clip intended to keep chips fresh.

I hated coupons. The need for coupons. I wanted to pay this woman's difference. Two dollars she'd save and I wanted to give it to her so she could spend her time some other better way.

"Is that it?" Hand asked.

Mo and Thor were at the Walgreen's counter now. They'd brought Valentine's cards, a package of twelve.

"Yep," Mo said.

"Do you sell stamps?" Thor asked the clerk.

"No," said the clerk.

"You should," she said.

"$23.80, please sir," the clerk said.

"You getting any sunblock?" Hand asked.

I was not there.

"Will."

I heard my name but couldn't find my way to my mouth. I'd been hearing everyone talk but was not at all present.

"Will."

I crawled back into my head.

"What?" I said.

People say I talk slowly. I talk in a way sometimes called

"Sunblock," Hand said.

"No," I said. He added a tube to my pile.

|

In the parking lot we watched a trio of milk-white Broncos drive by – - we all stopped momentarily to watch. It was bad enough that they still made them in that color, and to see three at once seemed to bode ill. The girls were unimpressed, and I was not surprised. I'd given up trying to predict what would impress them. Just a few months before, we'd seen a grown man, older and babbling in what sounded like Russian, jogging down the street in a great blue butterfly costume, and they thought that was great. But the Broncos did nothing for them.

We passed a teenage couple in leather and studs, she with a mohawk and he with shaved head, his dented bruise-blue skull covered in messages rendered in ink the color of raw meat.

Mo got a running start and – "HiYA!" she yelled – kicked the man in the thigh. He was shocked. Hand and I were less shocked. The girls were learning karate at school, and liked to try it out on people who looked combative.

"Daaaaamn… freak," the skull man said, wiping the footprint off his jeans. I apologized. I gave Hand a look, making sure he didn't start talking.

"They're not well," Hand explained.

The skull man looked at me and blinked meaningfully, suggesting potential aggression. I had him by ten pounds; his outfit was apparently giving him strength. I couldn't decide if I wanted this confrontation, if I wanted to leap from it, to make something explosive and open-ended – where would it end? I could ratchet this to true conflict and find some kind of deliverance – half of me was boiling, had been boiling for weeks or months or more -

Skull-boy and his friend pretended they thought Mo's attack was funny – they didn't – and kept walking. I exhaled and we did a serpentine Chinese dragon sort of run to the next block, all four of us yelling the chorus of "Froggie Went A-Courtin'."

We dropped the twins back at Jerry's, limiting conversation with Melora to our grunts and her squinting hisses, and we sped to the UIC hospital to get shots. The nurse, Glenda, about seventy with skin like redwood, pretended to be mad at us.

"You're leaving when?" A coarse but lilting voice, half Chicago, half country.

"Tomorrow," we said.

"You're going where?"

"Greenland."

"Greenland? There's no malaria in Greenland! Why you want a malaria shot? And what happened to your face, honey?"

"Car accident," I said.

"We might go to Rwanda," Hand said.

"What? Which is it?"

"What do you mean?"

"You just said you was going to Greenland."

"Well, maybe both."

"It can't be both. Are you relief workers or something?"

Hand nodded.

"No," I said.

"You two are confused. How old are you people?"

"Twenty-seven," I said.

"And you don't have health insurance?"

"He does," I said.

"No I don't," Hand said. I thought he did.

"Well you can't get Larium today. You haven't had a consultation. What's the rush?"

"We only have a week," Hand said. "Can't you consult with us? We're all here. Let's consult."

"No, with a doctor, honey. It takes an hour. If you came back tomorrow I could arrange it."

"What can you give us without the consultation?" I asked.

"Typhoid and Hep A, B and C."

"No malaria, though."

"No. You need a consult. If you get malaria you're gonna be regretting your big rush."

"Is it fatal? Malaria?" I asked.

"Always," said Hand, junior scientist. "It's bad-ass."

"Sometimes," Glenda corrected.

"When is it not fatal?" I asked.

"You'll live, if you get to a hospital."

"Good," I said. "We'll get there."

"We can drive. We're fast," Hand said.

"Stay in at night," she said as we rubbed our arms. "You in Rwanda, any mosquito might have it."

We thanked Glenda. She sat on her steel stool, waving goodbye with both hands, like a child popping bubbles from the air.

Through the hospital lobby I was following Hand and came around a corner to find him talking to a woman in a lab coat.

It was Pilar.

"Hey," I said. She looked so slight.

"Hi," she said. We hugged and she smelled, as always, of dogs and some kind of mint. She felt weightless. In high school she was robust, an athlete with broad tennis shoulders, but now she was rangy, her eyes bigger, cheekbones shooting angrily forward from her ears like dowels bowed. She'd dated Jack years ago but I bucked against the assumption –

"What're you guys doing here?" she asked. "What happened to your face?"

We told her about the inoculations, the trip.

"You don't need that stuff for Greenland," she said.

We tried to explain – the destinations beyond, everything.

"What about your face?" she asked again.

"I fell," I said.

"Liar."

"What are you here for?" Hand asked.

"I work here. In the lab," she said, sweeping her hands down her coat, bringing Hand's attention to the obvious.

"Oh," he said.

"So why a week?" she asked. "Why not really do the trip right, like take a summer or something? You won't see anything this way."

I opened my mouth but couldn't think of any way to answer. Someone was using my head to power a coffeemaker.

Hand was looking, thoughtfully, at the ceiling, while whistling soundlessly. Pilar, olive-toned and in high school dazzling and much-coveted, had given me one night, after she and Jack were no more, though it was obvious then that it was Jack who she cared for and I was a consolation, an approximation. Between Jack and Hand, both with easier smiles and better facial structures – beaten or not – it was a feeling I'd come to know well.

"We only have a week," I said.

Pilar brought her fingers to her temples in a way one would if attempting to keep a flood within.

"Migraine?" Hand asked.

"No," she said. "I mean, yes."

"It's good to see you," he said, putting his arms around her. After a second he stepped back and I stepped forward and held her and then we all stood for a moment, waiting for someone to tell us what to do. A voice on the intercom was looking for someone. It sounded like

"That's really his name," Pilar said, then sobered. The man's name knocked the wind out of her.

"Well," Hand said.

Pilar made a V of her hands and set her chin between her palms. Her eyes darted between us and quickly welled.

"It's awful to see you two."

We stayed up until four, in my kitchen, trying new itineraries and reading the Greenland website. The flight was eight hours away.

"Biggest island," Hand said.

"Official language is Greenlandic," I noted.

"Not just Greenlandic -West Greenlandic.

"Total population is 53,000."

"Ice covers eighty-five percent of the landmass."

"They're desperate for tourists. They get about 8,000 a year, but they're shooting for 60,000."

"They name their winds. Listen:

"What's katabatic?"

"Technical hitches. Are they talking about the weather?"

"I think so."

We fell asleep in the living room, Hand on the couch and me on the recliner, and at eight woke with two hours to gather everything and go. We had agreed not to pack before the morning, and this turned out to be easy to honor, the actual packing involving the stuffing in of two shirts, underwear, toiletries and a miniature atlas, which took three minutes. Passports, tickets, the $32,000 in traveler's checks, the bandannas. Hand brought some discs, his walkman, a handful of tapes for the rental cars, some State Department traveler's advisories, and a sheaf of papers he'd printed from the Center for Disease Control website, almost entirely about ebola. He could talk forever about ebola. I threw in a Churchill biography I was reading, but after swinging the pack over my shoulders and feeling the weight of the 1,200 pages, I unpacked the book, ripped out the first 200 and last 300, and shoved it back in.

We fell back asleep on the couch. At ten-thirty, with a spasm we woke again -

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |