"You Shall Know Our Velocity" - читать интересную книгу автора (Eggers Dave)

THURSDAY

We woke up late. It was 9 A.M. already.

"What a waste," Hand said. "We could have slept in the car on our way somewhere."

"We'll be fine."

"We really have to move."

We were throwing our stuff in our backpacks.

"Did you get up last night?" I asked. "I woke up at 2:30 or something and you were gone."

"Yeah, I woke up. You were talking in your sleep."

"What'd I say?"

"Nothing sensical."

"So you left?"

"I went down to Raymond's."

"No."

"I did. Man, that guy -"

Someone knocked on the door. I opened it; a very small woman gestured that she'd like to clean the room. I apologized and said we'd be leaving soon. She smiled and bowed and backed out.

"Wait," I said. "What's that smell?"

"It's you. You smell."

"It's us. We smell."

I inhaled from my underarm. The smell was very strong. "We'll have to wash these things. We'll soak through everything today." We'd figured out long ago that it wasn't the first-time sweat that created odor. It was the second time sweat came through once-exposed skin or cloth. It was the

I showered with great joy. In the shower, swallowing water, the water broke and hissed on my head, while heavy drops, after loving my abdomen, touched, rhythmically, my insteps. I said to myself, actually whispering out loud, that it was the greatest shower I'd ever known.

We drove to the airport and made for the Air Afrique desk. Behind the counter were three queens – grand, dressed in the most florid and glorious wares, skin luminous like lanterns polished.

We asked what they had flying out.

"Where are you going?" they asked.

"What do you have flying out?" I asked.

"You do not know where you are going."

"Well, yes and no."

They had a flight to Mauritania, but Mauritania wanted a visa.

"Anything else?"

"There is a flight tomorrow to Casablanca."

Morocco required no visa. But we'd have to stay in Senegal one more night. Which meant more waste, and the diminished likelihood of us making it around the world. We were failing in every way at the same time.

We made sure there was room on the flight and decided to decide later. We left the airport, heading for the coast, for Saly, where there were beaches. First we had to swim. Then we'd see the crocodiles and the monkeys. Then to Gambia and back. We could make it, we figured, but we'd have to speed.

We were lost before we left the airport complex. In front of an abandoned hangar we stopped for directions. There were about thirty men there, half in suits, standing in the parking lot adjoining the airport. A contingent of five approached the car. We explained where we needed to go, Saly, and instead of directing us, two of them began arguing, each with his hands on the back door handle. We asked again for directions. Directions only, we said.

Then a young man was in the back seat.

"I take you there," he said.

"What?" Hand said. Hand was driving.

"I show you the way, then you pay me, no problem."

Hand looked at me, I looked at Hand.

"I show you you pay me no problem," he said again.

His name was Abass. He was younger than us, wearing a nylon sweatsuit; he sat where the officer had sat, and I surprised myself by being glad he was there. It was good to be three.

But in a few minutes he had us on the road to Saly and had rendered himself redundant. I checked the map and noted that there were no turns for the remainder of the hour-long drive.

"Shouldntwejustdrophimoffnow?" I asked.

"Ithinkthat'dberude.Maybewetalktohim,pickhisbrain -"

He stayed. We liked him. He liked Otis Redding and Hand had an Otis Redding tape so we played James Brown. He liked, most of all, Wu-Tang Clan, but we didn't have any Wu-Tang Clan. We had Dolly Parton.

The road was an endless marketplace; the kind of road bearing strip malls and fast-food outlets in the U.S. but here tire shops, refrigerator outlets and open-air fruit stands. Three gangly boys playing foosball at a table five feet from the road. Small buses, bright blue and painted with joy by hand, overfilled with people. When passengers wanted to get off, the bus slowed and they jumped from the bus's back door. The bus never actually stopped. The children were filthy but the Mobils and Shells were pristine, as were the adults. Everywhere were people in dashikis, long enough to brush the unpaved shoulder but still unbesmirched.

The light was the familiar dusty white. I decided that when we got to Saly we'd give Abass half of what we had left on us – about $1,200.

"You have wife?" Hand asked.

"No, no. Soon," he said.

"Kids?"

"No, no. Soon."

"Girlfriend?"

"Yeah! Yeah!"

"Nice girlfriend?"

"Yeah!" he said, holding up three fingers. Three girlfriends.

What would he do with the money? Start a business? Buy his way out of Senegal? I didn't have the tools to imagine.

At a stoplight, a man was selling orange juice. We flagged him over. He came to the window. But it wasn't orange juice. It was brake fluid. He was selling brake fluid and cassette tapes. Behind him, an enormous pile offish, the shape of an anthill, lay rotting in the sun.

"We should let him get off here," I said.

Hand made the offer. Abass shook his head and smiled.

"He wants to go to Saly," Hand said.

We drove on. Hand and Abass were talking about something that prompted, from Hand, many expressions of surprise. He turned to me.

"I think he just said his father was the ambassador to Zaire."

"Tell him congratulations," I said, wondering why the son of an ambassador was in our car riding to Saly.

Hand and Abass exchanged words.

"He's dead ten years," Hand explained.

We expressed our condolences. I handed Abass a chocolate chip energy bar. He pointed out the front window, at a French army truck passing us going the other way.

"Ask him his last name," I said.

Hand asked.

"Diallo," Abass said.

"Really?" Hand said.

Another French troop truck.

"Tell him," I said, "we have a very famous Diallo in America."

Hand told him. Abass was very interested.

"Abass wants to know," Hand said, "what our Diallo did to become famous."

We drove in silence for a second. I knew we'd never be able to explain it, and we didn't want to spoil the mood.

"Tell him he's a singer," I said.

At Saly we turned off and drove under a series of canopied entranceways. This was a resort complex and the foliage quickly became more lush, the streetsides uncluttered – like entering a Floridian national park. We pulled into a hotel called Savana Saly and in the lot, stepped out and stretched.

I was getting the money ready – this particular wad drawn from my inner-waist pocket, under my belt – when he told us how much he wanted.

"What?" said Hand. Abass spoke quickly and sternly. They exchanged words. "I think he wants $80."

"Eighty dollars for getting us on the highway?"

"I guess so."

"That's too much," Hand told Abass.

He glared at Hand. Now he was not our friend. Eighty dollars for three turns and an hour on the highway.

He spit more words to Hand.

"He says he has to get a cab back to Dakar," Hand said.

There was no way he was getting a cab back to Dakar. He'd take the bus and pocket the $80. We didn't like him. He knew we'd feel awful paying him less than what he asked, but $80 was wrong. I looked up and the sky gave me no tether. We'd been driving too long and we hadn't eaten -

"Will."

I wanted a ceiling but it was too thin and porous and I went dizzy. I wanted something accountable above -

"Will."

"What? What?"

"Your pocket. The bills."

"Sorry."

I gave him the $80 but not the $1,200 I planned. He took the money and wrote his name and number on a piece of paper, urging us to call if we needed help getting back to Dakar. We said we'd be sure to call. The fucker.

He walked to the highway. Hand and I stood in the lot watching his back, my fingers tingling, my head in a half-swoon.

"That's too bad," Hand said.

In the hotel's reception desk, outside and under a thatched roof, an exhausted melange of French tourists sat on their suitcases, waiting for deliverance. They stared at us dismissively. We checked in, dropped our things in our dark cool room. The fan overhead spun crazily. It was missing a screw, and everywhere there were pictures of parrots and peanuts.

We went to swim. At the snackbar, we bought cold orange Fantas and carried them in our shoes, which hung by their heels from our fingers. We brought one backpack between us, stuffed with towels from the room and my Churchill pages.

The beach was slim and rocky, the water a vibrating cobalt blue. The bathers were old and white, flesh melting downward, the men in bikinis, the women, half of them, topless and drooping without caution. Hand ran, jumped on and from a huge grey gumdrop rock and into the sea.

"Fuck!" he yelled. He stood waist-deep, his hands shot to his face. "It's fucking cold!"

But he stayed.

I stepped in; it was brutal. The air was about 90° and we expected the water to match this, or come close. But it was crisp, bracing. The cold of an upper-Wisconsin lake, in June.

I wanted to be hotter before I jumped in, I wanted to be soaked. I spread my towel and I lay my head on the sand and listened. A bird, fifty feet above, fell from the sky like a plane. But in a second it rose, fish in beak, and flew toward the white shore.

I rested my head deeper into the terrycloth and closed my eyes. Only on sand like this did I ever feel like I could sleep forever, did I feel that sleep could be a destination, like a warm island full of food. The comfort was limitless and I knew I was mouthing the words

I came to the answer.

Hand had turned off the rental truck's ignition. I'd told him not to. Or were we low on gas? Couldn't be. I shouldn't have left the truck running. How long had I been in here? I had lost my sense of time. There was a gas station next door so it hardly mattered.

"Hand?"

Nothing.

I heard voices outside the unit, moving closer. I put the drawings back in the box. I stood up, my back to the door. The floorboards of the unit creaked, and as I turned, something struck my jaw. An airplane made of concrete. I dropped to my knees. Instantly the same thing, or something else like it, hit me in the back.

It had been years since I'd taken a punch. Had that been a fist or a club? A bat. A fist to the jaw then a bat to the back. Not a fist; too hard. A two-by-four, both times. I looked around for who but saw only floor. Then a pair of shoes so close, workboots, black, and behind them, a pair of white sneakers. Another pair of shoes maybe. Two guys, or three. I got on my knees and put my arms forward, bracing myself, and tried to lift my head. A corkscrew pain tore through my spine. I tried to speak but couldn't – lungs aflame. I fell forward, my hands catching me before my face hit the floor. "What the fuck?" I said. Cheek on the cool wood floor, I could make out three figures. There was blood in my mouth. It came down my chin as I spoke.

I tried to look up again but almost fainted from the pain. I sat up, head down, and wiped the blood with the butt of my hand. I looked around for a weapon. My back felt broken. It wasn't a dull pain; it was acute, almost sweet.

One of them laughed. A laugh like a cough.

The toe of a shoe ripped through my stomach. I lost my lungs. I spit a wad of blood on the threadbare Indian rug Jack used to have in his bedroom. I just needed a second to catch my breath. Goddamn, I just needed a second -

"Answer me!" a voice yelled. I hadn't heard the question. On my knees but upright, I swung wildly, connecting with the metal wall of the unit. It made a small sound, quick and weak. Skin from my knuckles remained on the wall, white with red streaks. The near one laughed. And then kicked me square in the chest. My head hit the floor this time. I couldn't break its fall. I tried to stop it but my hands felt so small. Then the end of the two-by-four came down on my right hand, like a shovel.

I blacked out. When I opened my eyes it felt like hours since I'd seen life. I felt like I was sucking air out of tiny crushed lungs. Lungs the size of thumbs. I didn't see an end to it. I just needed a breath, though. Just a second. But to die this way -

I wasn't recovering. My lungs were so small and burned when I tried to yank air into them. I wanted a gun. They had the wrong guy. I tried to say something but when I tried went blind with tears. My lungs had been doused with lighter fluid and set ablaze. What did they want? Everything spun beneath me.

My breath was coming back but my hands were crushed. And if I found something and used it on one of them, the other would be there. Only a gun would work here. Two guns. A knife. I would at least do some damage. I hated the odds. They'd blindsided me and there were two of them. I had almost no options. Where the fuck was Hand? Any second he'd show up with a bat and crack open heads. I longed for the sound.

One of them yelled something. I think it was "Answer me!" again. My hearing was filtered.

I started to stand up. The close one grabbed my hair. I slapped his hand away – I had more strength than I thought. A chunk of my hair went with his fingers. I took two steps back and tripped on fragments of a table. I was down again. The close one was still laughing. I tried to yell but it retched out in a whisper. My spine was a pole jamming into the base of my skull, a broom ramming into a ceiling.

"Fuck you!" the far one roared. It was so loud in the steel box I flinched. The far one stepped inside and turned off the light. The boot came from below and connected at the right side of my head and I was out.

I woke up alone. There were only my eyes. They felt as if they'd been removed, dipped in acid and then fastened to me with pins. The planks were oak, very old, rounded on their edges. My right palm met the wood and my cheek was set upon my hand, but the other hand I couldn't place. I felt nothing in the direction I assumed it would be. I opened my eyes again. There was no dog. I thought I had heard a dog.

I tried to sit up but my head was too heavy. I could lift my cheek but not my skull. I was afraid to pull it away from the floor, for fear I would tear something. I lowered my cheek again and slept. A crash woke me and I sat up quickly with the sound of ripping. I felt my head where it had been attached to the floor. I gagged and spit. I wiped my hand on a box behind me, not looking. I didn't want to see anything white, any bone on my hands. I felt my neck, to see if blood was coming steadily, which meant I was dying, but it was not. I looked to the floor, where my head had rested, but there was only a small black pool, the edges dry. I couldn't have lost much blood. A dog's face appeared at the door and then was gone.

I was using my right hand but couldn't feel my left. I realized I was not feeling my left. Where was my left arm? I looked to where it would be and found it, hanging from my shoulder like a windchime. It was dislocated or broken. My skull was something attached but so loosely. There was a pain so active and pulsating I was fascinated by it. It was unlike common head pain, which is dim and thudding; this was a constant cracking from within, a constant chopping of the inner walls of the cranium, by pickaxes. To see things hurt my eyes. I closed them. There were insects in my inner ear. Something rattled lightly. Then a high-pitched sound, like a whistle, though higher and more distant. I felt my face; the right side was numb. I shook my head slightly and the pain went stratospheric.

I slept for what seemed like hours. Finally I stood and immediately fell, as a flaming burst of glass shot up my left leg. The dog was there again. He was a collie, white and khaki, and stood in front of the door to the unit. I opened my mouth and closed it. The truck was in the same place. The windshield was cracked up the middle, one large split giving way to dozens of white tributaries. I was sitting down and had no idea how I could get there.

I heard his footsteps on the gravel. Hand.

"Jesus fucking Christ!" he said. "What the fuck happened?"

I hated him. This was for him. They were here for him.

"Tell me!" he said.

"Where were you?" I breathed.

"What the fuck happened?"

I gathered my voice. "Where were you Hand?"

I raised my head and sat up. The beach was the same. Hand was further out, swimming with his perfect stroke toward a small fishing boat. I stood and almost collapsed. I grabbed my knees and rested and rose again and waded in, still reeling, and the hands of the cold calm sea held my calves then seized my knees and wrapped its thick strong fingers around my thighs and its bony cold arms around my waist. I dunked my head and came back wet and stronger.

I pushed my hair from my face and smoothed it in back, letting the water exit my mouth and spread slowly down my neck. Hand lifted himself from the water so his head peeked into the empty boat. I couldn't see what was there. But he was often finding things. He swam back; the boat was empty.

On the shore we dried in the sun. Far away, a fishing boat with an old man pulling from its side a huge fish, or a part of it. It looked like a swordfish, huge chunks torn from its sides.

"Scavenger fish," Hand said. "They bite and disappear down."

"Poor man."

"Turn around," Hand said.

"Why?"

"You didn't show me that shit. Jesus."

"What?"

"Have you looked at your back?"

"No. Sort of."

"Fuck, man. You've got a huge bruise here -" he pushed his finger into the lower part of my left lat – "and right here" – he brushed his hand over my right shoulder – "it's all red and scratched. It's just nasty."

"Doesn't hurt back there."

"Well, good. It's nasty-looking."

– You act like it wasn't your fault.

– We've leapt over that.

– I'm not sure I have.

A strong-shouldered woman was playing with four small children by the water. They had buried the tallest of the kids and were giggling like henchmen. Their dog walked to us and waited for our attention. It was a small white thing with short legs, trailing a leash. This one was winking at us.

"He's only got one eye," said Hand. It was true. I scratched the dog's head. Half the animals in my life were missing an eye – growing up we'd fed nuts to a cycloptic squirrel, Terrence, that lived on our roof – and I couldn't figure out if this was good luck or bad. The dog's one eye was wide open and the other was closed tight around the vacancy. It was grinning, though – was accustomed to being appreciated.

As the tiny waves came to wet the sand with long hisses, I picked up my Churchill. Now he was at the Admiralty, whipping everything into shape, trying to increase the production of ships, honing his speechmaking skills, having the first of his children, writing beautiful letters to his Clementine. I'd never written a beautiful letter to anyone, and I had never fought the Boers, had never righted a derailed military train at Frere, never faced their artillery fire while loading wounded onto the cab and tender -

– Churchill what would you have done?

– When?

– In Oconomowoc.

– What? What are you talking about?

– I was beaten. They hit me with bats. I was in a storage unit, gathering Jack's stuff, just going through it, I guess I was lost a bit and Hand was gone -

– Where was Hand?

– He went off, up the hill.

– Hand should have been there.

– I know. But if I allow myself to know that I'll leave him, and I don't want that. I do want it, so often, but I'm stuck with him, worse off without him, if you can believe it.

– I can.

– So what would you have done?

– I can't say. The odds sound difficult.

– I would have fought next to you, Churchill. Anywhere. Did I tell you that? In India, I would have been there, leaping into musket fire. In Egypt, surveying the Dervish army at Surgham Hill, I would have been there. Cavalry, infantry, whatever -

"We should leave," I said.

"Right," Hand said.

We dressed quickly so we could drive through the countryside and tape money to donkeys. We'd been in Senegal for twenty hours and hadn't given away anything.

I drove. I drove fast. The road was dry, passing through scrubland and the occasional farm, the roadside spotted with small villages of huts and crooked toothpick fences. The terrain was dry, the grass amber. We passed more blue buses bursting with passengers, staring at us, at nothing.

The donkey plan was Hand's. As we drove, hair still wet, we looked for donkeys standing alone so we could tape money to their sides for their owners to find. We wondered what the donkey-owners would think. What would they think? We had no idea. Money taped to a donkey? It was a great idea, we knew this. The money would be within a pouch we'd make from the pad of graph paper we'd brought, bound with medical tape. On the paper Hand, getting Sharpie all over his fingers, wrote an note of greeting and explanation. That message:

|

We saw many donkeys. But each time we saw a donkey, there was someone standing nearby.

"We have to find one alone, so the owner will be surprised," Hand said.

"Right."

We drove.

"This looks like Arizona," Hand said.

"It was pretty lush in the resort, though."

"Watch it."

I had driven off the road for a second, with a whoosh of gravel and a tilt of the passenger side, then back on, level and straight.

"Dumbfuck," Hand said.

"I've got it. No problem."

"Stupid. Listen."

There was a flopping sound.

"Pull over," he said.

We had a flat.

We stopped. When we got out, all was very quiet. The earth was flat and the savannah was broken only by large leafless trees, bulbous at their trunks and muscled throughout. A bright blue crazily-painted bus, full, drove by; everyone stared. The sun was directly above.

We got the spare and the tools and jacked the car up. We started on the lugnuts, but they were rusted and weren't budging. We pounded them with the wrench with no results. We sat on the highway next to the car, suddenly both very tired. The pavement was so warm I wanted to rest my face on it. I imagined what lay ahead: hitchhiking to the next town, maybe catching the bus, then finding our way to some kind of garage, then negotiations with the mechanics, a towtruck back, then, hours later, the fixing of the flat. We'd waste the day. We'd already wasted too much.

A man appeared behind the car. In a purple-black dashiki, easily seventy, with a small square jaw and eyes small and black and set deep under his brows. He said nothing.

He inserted himself between me and Hand and, without a word, took over. He first placed a rock behind the back tire, to prevent rolling. We had forgotten that. Then, crouching, with hands that hadn't, it seemed, seen moisture in decades, wrinkles white like cobwebs, he lowered the jack so the wheel rested on the road. He stood and with his sandaled old foot he kicked the wrench; the lugnut turned. He kicked again for each nut, and in a minute the tire was off.

"Leverage," Hand said to the man, touching his shoulder. "You are very good man!" he said, now patting the man on the back.

I laughed at our incompetence. The man chuckled. He looked at my face and smiled.

I put the new tire on, and the man allowed me to tighten the lugnuts myself. When the job was done the old man turned and walked away. He still hadn't said anything.

"Give him something," Hand said.

"You think?"

"Of course."

The man was now across the street, heading down the embankment and into the tall grass.

"You think it's an insult?" I said.

"No. Go."

"In America that would be an insult."

"This is different."

I grabbed a bunch of bills from my thigh pocket.

I ran after the man and when I descended the embankment I realized I was barefoot. The rough earth scratched my soles but I caught him fifty feet into the opposite field.

"Excuse me!" I said, knowing he wouldn't understand the word, but knowing I had to say something, and then settling on the words I would have said had he been able to understand. He turned to me.

I smiled and handed him a stack of bills. He stared at my nose. I smiled harder and rolled my eyes.

"Long story," I said.

He waved the money off. I took his hand and put the bills in his palm and closed his fingers, dry and ringed like birch twigs, around them. I smiled and nodded in an eager and anxious way, like I was taking his money, not giving him mine.

He said nothing. He took the bills and walked off. I jogged back to the car, my feet slapping the pavement in a happy way; a boy was there, about six years old, though there wasn't a house or hut in sight.

"Where'd he come from?" I asked.

"He just showed up," said Hand.

The boy, barefoot and wearing Magnum P.I. shorts, was leaning against the side of the car, looking inside, his hands cupped around his eyes and set against the window, reflecting the endless fields, newly tilled and dry, behind him.

"What's he want?"

"I think he was here to help."

"We have anything for him?"

"Money."

"No. He'll get robbed."

We gave him a package of white cream cookies and a liter of water, full and in the sun seeming heavy, like mercury.

We got in the car but the car wouldn't move. The boy, at the side of the car, yelled something, waving his tiny bony arms.

"The rock," said Hand.

"Oh," I said.

While watching us, carefully, holding his hand up in a gesture begging us not to run him over, the boy bent down and removed the rock. We thanked him and waved and honked and drove away, down the coast.

There were beaches being used as dumps. The sand was white and duned, and the water clear beyond, but the beach overwhelmed with garbage, great heaps of it, and broken boats. Periodically we'd pass through a village, the buildings, squat and of clay, abutting the road, kids running out of open doorways. We drove around more blue buses, and a few carts driven by horses nodding, but no donkeys. We couldn't find a fucking donkey. Cows would be just as good, we thought, but every time we stopped and approached a cow on foot, a car would come down the road, or a bright blue bus, or a farmer or a cart or child, and we'd abort. At one point, when we really thought we were going to do it, had the money in a pouch and the tape all around it and a cow picked out and were only a few feet away, it wasn't a car that came but a whole caravan of men, French we guessed, on four-wheel ATVs, eleven of them, in a row, half with white girlfriends strapped around their waists, all with aviator glasses, a few with scarves.

"Good lord God no," Hand said.

The image was unsettling and indelible.

"Did the old man say anything to you?" Hand asked.

"No."

"Huh."

"I think he felt bad for me. Like I should be using the money to get my face fixed."

Hand laughed quickly, then stopped.

"Sorry," he said. "How much you give him?"

"About $800, I think."

"That's too much."

"Why?"

"I don't know. Don't you want to spread it out more?"

"Why?"

"It makes sense, doesn't it?"

"No."

"I guess not."

We gave up on taping money to animals. We were now looking for people. Anyone to unload the money on. But choosing just who was a strange kind of task. We found a group of boys working in a field, raking hay and throwing it into a large wooden wagon attached to a mule. Five boys -

"Brothers, probably," said Hand. We stopped and parked on the the side of the road.

"They're gonna see us," I said.

"Then get out and give em some money, idiot."

"Not yet. I gotta make sure."

"Here," Hand said, spreading a map between us. "This is like a fucking stakeout or something."

– working together, without pause. They were perfect. But I couldn't get my nerve up. All I had to do was get out of the car, walk a hundred feet and hand them part of the $1,400 we had left. We had to get rid of this money. Tomorrow we would cash more checks –

"That one guy looks like a dad," I said.

"No, he's just a little older than the others."

"I can't give it to them if the dad's there."

"Why?"

"Because the dad won't take it, or let them."

"Bullshit," Hand said. "Of course he'd take it."

"No he wouldn't. It's a pride thing. He won't take the money in front of his sons."

"Not here, stupid. These guys know they need it and that we can afford it. They're not taking it from a neighbor, they're taking it from people who it means, you know, next to nothing to. They know this."

"You do it."

"No, you. It's your money."

"No it's not. That's the point."

"Just go."

"I can't. Maybe we wait. The dad'll go get some water or something. Or you could create a diversion."

We sat, watching.

"This is predatory," I said.

"Yeah but it's okay."

"Let's go. We'll find someone better."

We drove, though I wasn't sure it would ever feel right. I would have given them $400, $500, but now we were gone. It was so wrong to stalk them, and even more wrong not to give them the money, a life-changing amount of money here, where the average yearly earnings were, we'd read, about $1,600. It was all so wrong and now we were a mile away and heading down the coast. To the right, beyond the fields and a thin row of trees, the Atlantic – wait; right, the Atlantic – shimmered like a dime.

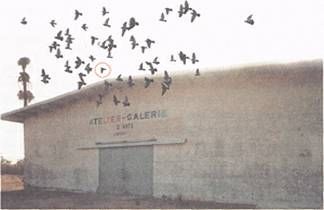

The sun was low in a white-blue sky and the air was cooling. We approached a huge warehouse in a field. The place, a gallery of some kind, was immense, and shuttered, the parking lot covered in grass. There were no other buildings for miles.

We parked. We'd look around.

A flock of small black birds came across the building in a desperate way. They weren't in any kind of formation, just fifty of them, all flying in the same direction, each with its own path. Not every one with its own path, I guess, but so many of them, which struck me. I don't know why it struck me then but had never struck me before. When we see birds flying in a flock, we expect them in formation. We expect neat V's of birds. But these, they were flying in more of a swooping swarm, a group fifty feet left to right, twenty feet top to bottom. Within that area they were swerving up and down, swinging to and fro, overlapping, like a group of sixth graders riding bikes home from school. Which would imply not only free will but a sense of fun, of caprice. I mean, I want to know what this bird:

|

is thinking. How does he feel his flight? Does he know the difference between stasis and swooping? Birds were so much better in flight. My bird feeder, now empty in Chicago, taught me how nervous and jittery birds were when they stood and hopped and ducked their heads into the glass for their miserable little seeds. But tearing in and out of formation, there was proof of -

And then they were gone.

"This is a good place to walk around," said Hand.

I agreed to walk around.

We parked the car behind the building, hiding it from the road. Though we had no evidence of anything like it, we imagined the possibility of roaming marauders who would stop, strip our car bare and move on. So the car was hidden; we could walk through the fields and head to the ocean, less than a mile west.

"You got some sun today," I said.

"You too," Hand said.

"Let's go that way," he said, vaguely indicating a small farm in the distance, three small huts and a fence of sticks. This would be the first walking we'd done. The field was quiet. We walked toward the huts, over rough savannah breached by the huge and common bulbous leafless trees – one is at right – their bark smooth and knotted. Closer now, there were figures under and around one of the farm's largest hut, and around the hut a fence and within the fence ten or twelve sheep, all a dirty grey. Four young kids ran from the fence and toward us, still very small in the distance.

"Bonjour!" one of them yelled, the word sailing to us through the thin late-afternoon air with the strong voice of a girl of eight or nine. Then another one, "Bonjour!" this time from a boy. Then they both said it as they skipped toward us: "Bonjour!"

Hand yelled back: "Bonjour!"

"Hello!" I yelled.

It had to be those kids. Only the most blessed of little people yells hello across an empty field to strangers with dirty clothes.

"We have to give them some," I said. A man emerged from another nearby hut and faced us. "Shit," Hand said. We only wanted the kids. This man would be suspicious.

"I liked it better when it was just the kids," I said.

"Who cares?"

"Look at him. He's carrying a scythe or something."

Hand squinted. "You're right."

"I am?" The man was standing now, hand shielding his eyes, and the kids had gone inside.

"We'll come back," Hand said. "We'll swim and come back."

We walked toward the ocean; we knew it wasn't far. We'd been watching the ocean peek between towns and trees the whole drive down. We tramped through a growing thicket and toward the weakening sun.

"Fuck," said Hand.

"What?"

"Mosquitos. That's how we get malaria."

He was right.

"You bring block?" he asked.

"No."

"Fuck. This is stupid. I don't want malaria."

"I wouldn't mind it," I said. I had a distant and untested fascination with sickness like that, that would bring you to the brink but not over, if you were strong.

We debated. Continuing on meant an unknown risk – the place could be swarmed with mosquitos any second – but going back to the car meant that we'd truly done nothing, and we would never do anything. If we couldn't pull off the road and walk through a field to the ocean then we were worth nothing.

We walked on. The ground was hard and brown and dotted with seashells. There were shells all the way back to the highway, the road lined with them, white and broken.

"You see all the shells?" Hand asked.

"I know."

"This whole area was underwater."

After a few minutes we could see the ocean. It was the lightest blue, a dry and sun-faded blue. We walked closer, a few hundred yards from the shore, and saw a group of small houses, all of the same design and standing in formation – some kind of development, between us and the water. About fifteen of them, cottage-sized and neatly arrayed, on a sort of plateau, separated from us and from the beach beyond by a moat, sixteen feet down and filled with what seemed to be -

"Sewage," I said.

"I know."

"Brutal."

The builders had run out of money. It was a resort-to-be, but without any sign of recent work. There were no vehicles or trailers. Only these small homes, well-built, windowless and sturdy. Each one big enough for one bedroom, a sitting room and a small porch. We got as close as we could before the moat asserted itself without solution. The water in the moat was too deep and dirty to wade through, and too wide to jump.

"There is no reason for this moat," said Hand. "Someone built this moat and even they don't know why."

There was a man. He walked into view on the other side of the moat, among the houses. He was Senegalese, bone-thin and holding in his hand some kind of electric device, black and with a long antenna. He stared our way.

"Security," Hand said. "They've got someone guarding the whole place."

"We should leave."

"No."

We were watching the man and he was watching us.

"Let's pretend we're leaving and see if he leaves," I said.

"Fine," Hand said.

We turned and shuffled away. Was he armed? He could shoot us if he wanted to and no one would ever know. We sat behind a pair of thick shrubs.

"Pilar looked thin," I said.

"She did?" Hand said, trying to balance a thin stick between his nose and upper lip. "I thought she looked normal."

"You're blind."

I dug a small hole and put a scallop-shaped shell inside, and buried it. Then I retrieved it, and set it back in the exact spot I'd found it.

"This is slower than I thought it would be," I said.

"It's good though," Hand said.

"We're still wasting time," I said. "We still have $1,400 or something."

"You're the one who's got to decide what he wants to do. I'm along to help, but for example what are we doing here?"

"I know what I want to do."

"Well which is it? What is this, for example? This isn't helping with the money thing. There's no one out here. And we've already been swimming today so -"

"We saw the water and wanted to walk. And now there's this moat and we have to – you know."

"I guess," he said.

Under the shadow of Hand's back, ants walking in a loose capillary line. Hand got up quickly, convinced they were red.

"I just like it out here," I said.

I did. I pictured myself in one of those half-built homes, squatting and on the water. I could have a car, park it behind the warehouse and live here, for free, under this sun and with this water, protected by this moat -

I stood and the man was gone.

"Let's go," Hand said.

We walked alongside the moat, hoping to find a narrow place to cross, to get closer to the homes and then to the beach beyond. We soon saw a clothesline threaded between one porch and its adjacent tree. Shirts and pants hung from it, and on the porch towels and an Indiana University umbrella.

"Jesus," I said. "Someone's living here."

"Makes sense."

"But why does the security guy let them?"

"We could plant some money in there," Hand said. "Put it in a pair of pants."

"Yeah, on the clothesline. That'd be good."

We went around the entire moat and at the far right end found an area where we could get down the bluff, about fifty feet, and over the water. There was a rocky sort of path sloping right and after taking off our shoes in case we landed somehow in the moat, we descended, sliding and jumping, and soon found ourselves jogging slightly, as if descending stairs in a hurry. The path was now dotted with large flat rocks, like overturned dinner plates, and we were jumping from rock to rock, and doing so at a speed that I should have found alarming but somehow didn't, and we were barefoot, which might have increased the alarm but instead made it easier, because the rocks were smooth, and cool, and my bare feet would land on the rock and kind of wrap around it, simian-like, in a way that a shoe or sneaker or sandal couldn't. I swear my toes were grabbing for me, and that my skin was attaching to the rock surface in a way that only meant collusion between natural things – in this case, feet and smooth green-grey rocks. There was no time to think, which was plenty of time – I had a few fractions of a second in mid-air, between rocks, to calculate the location of the next rock-landing options, the stability of each, the flattest surface among them. My brain and legs and feet all working at top speed, at the height of their respective games – it was thrilling and I was proud for them, for us. I had the thought, while running, without breaking stride, that I would like to be doing this forever, that thought occurring while I almost landed on a very sharp rock but adjusted quickly enough to avoid it in favor of a nearby and more rounded rock, and while I was congratulating myself on having made such a perfect rock-landing choice, I was also rethinking my thought about jumping on rocks forever, because that would probably not be all that fun after a while, involving as it did a certain amount of stress, probably too much – and then, I thought, how odd it was to be thinking about running forever along the rounded gray rocks of this corner of Senegal – was this Popenguine? Mbour? – while I was in fact running along them, and how strange it was that not only could I be calculating the placement of my feet in midrun, but also be thinking of my future as a career or eternal rock-runner, and noting the thinking about that at the same time. Then the rocks ended and the sand began and I jumped into the sand with a shhhht and my feet were thankful and I stood, watching the water and waiting for Hand.

We hopped from the middle to the side, into wet mud, the ground like wet velour. Then up the middle bluff, only twenty feet or so, and we were now amid the resort. The homes were unfinished inside, slate-grey adobe, dark and cool. We stood, turning in place, taking it in.

"I'm glad we did that," I said.

Hand nodded and stepped over a pile of plywood boards.

I tried to picture the complex as it was intended, in final form. The moat was an expansion of a stream that ran from the home next-door, a huge compound behind a high stone wall. There would be footbridges over the water, and lush gardens would be planted, narrow paths lighted by low tasteful fixtures rising from the tended lawns. But for now it was dry, with great piles of tubing and cinderblocks resting unused.

"We could stay here tonight." I said.

Hand looked around. "We could."

"We'd need some netting or something."

"Get some in Saly or Mbuu."

The man appeared again. He wasn't a man. He was about seventeen. In his hand wasn't a walkie talkie, or a gun. It was a transistor radio, fuzzily broadcasting the news.

"Bonjour," said Hand.

"Bonjour," said the teenager.

They shook hands, the man's grip limp and uninterested. He looked at me quickly, squinted and his eyes returned to Hand. In French, Hand asked if he was the guard. He shook his head. He was staying at a hotel nearby, he said, waving down the shore, and was just walking. He didn't speak much French, he said. He and Hand laughed. I laughed. We stood for a moment. The man looked at his radio and tuned the dial. I watched an ant hike over my shoe.

Hand said goodbye. The man waved goodbye and we walked on, toward the beach, while the man disappeared behind the cottages. But for us there was another moat, too, a much wider and more rancid one, separating us from the beach. We turned around. Hand had an idea.

"Let's skip the beach. I want to get back to that house and see who lives there."

"We'll do the clothesline."

We went to the house with the Indiana umbrella. It didn't look like anyone was home, so we could sneak in, dump the money in the pocket of the pants on the clothesline, and leave. That was almost better, we agreed, than taping it to the donkey. We crept around the house, past the line, our own skulking making the place seem more sinister. There was the dark and vacuumed smell of clay. This was the sort of place bodies were found. Bodies or guns. We peaked around, to the front porch.

Through the open front door we could see the corner of a bed, a calendar on the wall above it.

"You go," I said.

"You."

"You."

"You."

Hand stepped around until he was peering through the front porch of the house.

"Bonjour!" he said.

A man stepped through the door and into the light. It was same transistor radio teenager we'd just met. He wasn't happy.

Hand shook the man's hand again. The man was on his porch and we were below, grinning with shame. We said sorry a few times for intruding then Hand said:

"You live here?"

The man didn't understand.

"It's nice here," Hand said. "You're smart to stay here." He gestured to the house. "It's very nice."

The man stared at Hand. Hand turned to me and I understood. I took the money from my velcro pocket, slowly like a criminal would lay down a gun before a cop. I took the stack of bills and aimed them at the man. He didn't move.

"Sorry," I said, looking down.

"Can we -" said Hand, gesturing his arms like pistons, in a give-and-take sort of way.

"We want to -" I tried.

"Will you take?" Hand said, pointing to the money as you would to a broken toy offered to a skeptical child. But this money was new.

The man took the bills. We smiled. We both made gestures meaning:

The man glanced at the stack but didn't count the money. He held it, and smiled to us grimly. He turned and with two steps was back into his house.

The sun was setting slowly and the warm wind was good. We were giddy. There was a hole in my shirt, in the left underarm, and the air darted through on tiny wings. We were walking quickly back to the car, through the low brush. We still feared the mosquitos but hadn't yet seen any.

"There's nothing wrong with that," said Hand.

"There can't be," I said.

"We gave the guy money."

"How much was it, you figure?"

"It was most of what I had left. About $800."

"He took it, we left."

"Nothing wrong with that," said Hand.

"Not a thing. It was simple. It was good."

We believed it. We were happy. The absence of mosquitoes made us happy, as did the prospect of hearing from the kids again, running from their low fences to us.

We stood for a moment, squinting in the direction of their huts. We walked briefly toward their settlement, but the boy and girl were gone, or were being hidden from us and in a second the father appeared again, and he was holding something, a fireplace poker, a rod of some kind, a staffer walker or something more sinister.

We pressed on, retrieved the car from behind the warehouse and on the highway went the other way, Hand driving, back to the hotel. The day had been long, and soon we would stop moving and pushing and just rest. We needed to eat, and I wanted beer. I wanted four beers and many potatoes, then sleep.

And I wanted to stay in Senegal. It was the mix of sun in the air, mostly, but it was also the people, the pace, the sea.

"I want to marry this country," I said.

"It's a good country," Hand said.

"I want to spend a lifetime here."

"Yeah."

"I could do it."

"Right."

And my mind leaped ahead, skipping and whistling. In the first year I'd master French, the second year join some kind of traveling medical entourage, dressing wounds and disseminating medicine. We'd do inoculations. We'd do birth control. We'd hold the line on AIDS. After that I'd marry a Senegalese woman and we'd raise our kids while working shoulder to shoulder – all of us – at the clinic. The kids would check people in, maybe do some minimal filing – they'd do their homework in the waiting room. I'd visit America now and then, once every few years, in Senegal read the English-speaking papers once a month or so, slow my rhythm to one more in agreement with the landscape here, so slow and even, the water always nearby. We'd live on the coast.

"Sounds good," said Hand.

"But that's one lifetime."

"Yeah."

"But while doing that one I'd want to be able to have done other stuff. Whole other lives – the one where I sail -"

"I know, on a boat you made yourself."

"Yeah, for a couple years, through the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Caspian Sea."

"Do only seas. No oceans."

"Yeah but -"

"Can you sail? You can't sail. Your brother sails, right?"

"Yeah, Tommy sails. But that's the problem. It could take years to get good enough. And while doing that, I'm not out here with my Senegalese wife. And I'm definitely not running white-water tours in Alaska."

"So choose one."

"That's the problem, dumbshit."

We passed two more white people on ATVs.

"You know quantum theory, right?"

This is how he started; it was always friendly enough but -

"Sure," I lied.

"Well there's this guy named Deutsch who's taken quantum theory and applied it to everything. To all life. You know quantum theory, right? Max Planck?"

"Go on," I said. He was such a prick.

"Anyway," he continued. "Quantum physics is saying that atoms aren't so hard-and-fast, just sitting there like fake fruit or something, touchable and solid. They're mercurial, on a subatomic level. They come and go. They appear and disappear. They occupy different places at once. They can be teleported. Scientists have actually done this."

"They've teleported atoms."

"Yeah. Of course."

No one tells me anything.

"I can't believe I missed that," I said.

"They also slowed the speed of light."

"I did hear that."

"Slowed it to a Sunday crawl."

"That's what I heard."

We drove as the sky went pink then barn red, passing small villages emptying in the night, people standing around small fires.

Hand went on, gesturing, driving with his knees: "So if these atoms can exist in different places at once – and I don't think any physicists argue about that – this guy Deutsch argues that everything exists in a bunch of places at once. We're all made of the same electrons and protons, right, so if they exist in many places at once, and can be teleported, then there's gotta be multiple us's, and multiple worlds, simultaneously."

"Jesus."

"That's the multiverse."

"Oh. That's a nice name for it."

A man by the road was selling two enormous fish.

"Listen," Hand said, "if you're willing to believe that there are billions of other planets, and galaxies, even ones we can't see, what makes this so different?"

We passed a clearing where a basketball court stood, without net, the backboard bent forward like a priest granting communion. Two young boys, stringy at ten or eleven, healthy but rangy, one wearing red and one in blue, were scrapping under it, each ball-bounce beating a rugfull of dust.

"We have to stop," I said. We were already past the court.

"Why? To watch?"

"We have to play. Haven't you ever driven past a court and -"

"Will, those kids were about twelve."

"Then we won't keep score."

This could be something. This was something that could happen; we would stop and play against these boys. Hand slowed the car and turned around and on the gravel we crunched toward them. They stopped as they saw us approach. Hand got out and called for the ball.

Hand bounced the ball and it landed on a rock and ricocheted away. The boys laughed. Hand chased it down and returned and did some bizarre Bob Cousy layup, underhand and goofy; the ball dropped through the dented red rim. Hand shot the ball three times from the free-throw area, without luck. Now I laughed with the boys. I gave the boy in blue a handshake, making up an elaborate series of sub-shakes involving wrists and fingers and lots of snapping at the end. He thought I knew what I was doing.

I tried dribbling and lost it, like Hand, on a rock. I got the hang of the court, its concavities and dust, and soon it was a game, us against them. They weren't very good, these kids. One was barefoot and both were much shorter than us, and while I was trying to keep the game casual, Hand knocked the ball from the younger kid's hands and scored over him without apology. It was not cool.

The light kept leaking from the sky, blue ribboned by purple and then, below, thick rough strokes of rust and tangerine. Another boy showed up, bigger and more confident. He had newish sneakers and knee-length basketball shorts, a Puma T-shirt. He was serious. He smiled at first, shook our hands – another limp grip – but then he bore down and didn't look us in the eye. It was our two against their three and there was dust everywhere. The tall boy was determined to win. The game got closer. I tried to switch teams, to relieve the nationalistic tension, but the boys refused.

It was ridiculous for Hand and I to be playing like this; we weren't the players – Jack was, Jack was the best pure player our school had ever seen, rhythm and speed impossible, it seemed, in someone we knew, someone from Wisconsin whose father sold seeds. We played with Jack, were humored by him, but when he wanted to, or when we'd made his lead less comfortable and opened our mouths to make sure he knew, he turned it up and broke us like twigs.

Very soon there were ten kids watching, then twenty, all boys, half of them barefoot, most of them shirtless. Every time the ball bounced off the court and away toward the village, there were two more boys, emerging from the village and heading toward us, to reclaim it. We were holding our own, now against four of them.

Hand was posting up, Hand was boxing out. Hand is tall, but Hand cannot play, and now Hand was out of control.

It went dark. We were passing the ball and it was hitting our chests before we could see it. No one could see anything. We called the game.

We walked back to the car and brought out the water we had left, took pulls and handed it to the boy in red. Red handed it to the tall one, who sipped and gave it to the blue boy, who finished it. Another boy of about thirteen pushed through the crowd around the car, arced his back and said with clarity and force: "My father is in the Army. My name is Steven."

And then he walked away, off the court and back to the village. Other than that, there hadn't been much talking.

Now the tall Puma boy spoke. He spoke some English; his name, he said, was Denis.

"Where do you live?" he asked.

"Chicago," I said.

"The Bulls!" he said. "You see Bulls?"

Hand told him we'd been to games, even while Jordan was still active. And this was almost true. We'd been to one game, with Jordan playing the first half of a blowout.

Denis's mouth formed an exaggerated oval. Was he that good? he asked. Hand grinned: Yes. Denis said he'd love to come to America, see basketball, see his cousin, who lived in New Mexico. I told him New Mexico was very pretty.

"But," said Hand, "Pippen is the more elegant player."

Denis smiled but said nothing. Hand said this all the time: "Pippen is the more elegant player." The rest of it: "His movements are more fluid. Pippen is McEnroe to Jordan's Lendl." It was Hand's favorite thing to say, partly, surely, because it enraged anyone in Chicago who heard it.

Denis shook his head and smiled. He didn't agree, but kept mum. Hand asked for their names. He found paper in the car and a pen and had them write their names. They all wrote them on one piece of paper:

I lost this piece of paper. I am so sorry. I can't believe I lost it.

We didn't know if we would give them money. We got in the car and debated. The kids had seemed to be expecting something. They hadn't asked, none of them had, but it seemed they knew the possibility existed, that gifts of some kind could be forthcoming. They knew we could spare it. I still had some American hundreds in my shoes, but would that spoil everything? Would it pollute something pure – a simple game between travelers and hosts – by afterward throwing money at them? But maybe they did expect money; otherwise, why would they all gather by the car after the game? Maybe this was a common occurrence: Americans pull up, grab the ball, show them what's what, drop cash on them and head back to the Saly hotels -

"Let's not," Hand said.

"Okay." The boys surrounded us, waving. We began to roll away, driving the twenty yards back to the highway, as the boys went their separate ways. I stopped the car, alongside the Bulls fan who wanted to go to New Mexico. He and two friends were crossing the highway.

I rolled down my window and said Hey to the boy. He approached the window. I reached into my sock and grabbed what I could. I handed him $300 in three American bills.

"See you in Chicago," I said.

The boy thanked us. "If I get to Chicago it is because of you," he said.

"See you there," Hand said to Denis. To me: "We should get going." We didn't have enough for everyone, and there were a lot of kids.

We said goodbye to Denis, and his eyes were liquid with feeling and we loved him but there was a man in our backseat.

"This is my brother," said Denis. "He needs a ride to Mbuu."

I looked at Hand. Hand was supposed to lock the back doors. Denis's brother was in the car and it was too late; we had no choice. Mbuu was on our way. We said hello to Denis's brother. His name might have been Pierre.

We joined the highway with Denis's brother in our backseat and his chatter neverending. We didn't like him. Mbuu was twenty minutes away, and Pierre did not stop talking, in a language Hand couldn't grasp completely and could not at first confirm was French. We got the impression, immediately, that Denis's brother had seen his brother's receipt of cash, and wanted some of his own.

Pierre used Abass's line, that he needed cab fare to get back. Hand explained his demands to me. We laughed.

"So," said Hand, turning toward him, "you want

Denis's brother nodded emphatically. Denis's brother was not very good at this. He didn't know what Hand was saying. Hand laughed. "You are not such the clever guy," said Hand. "Your brother he got all the brains, eh?" Hand was getting overconfident; the man knew no English, but continued nodding eagerly. "But you know why," Hand continued, "we gave to your brother three hundred of the dollars American? Because he didn't ask for it. You, you are crass – you know of this word, crass? – so no money you have coming."

With that, the man began chattering again. We had no idea what he was saying, but his voice was impossible to bear – an uninterrupted belligerence to it that was sending me over the edge.

Like the police officer before him, this man had his hand in my backpack, which was still on the backseat. I reached back for it, telling him, with a tight grin, that I needed something inside. I brought it into the front seat, fished through it, found a comb and ran it through my hair in an elaborate way, demonstrating how badly I missed it, how badly in need of grooming I'd been, this night, driving in the black to Mbuu.

The man began talking again, but he had changed tacks: now he needed the money to go to Zaire. He had gleaned that we had donated to his brother's designs on Chicago, and he assumed we were providing grants to all travelers.

– You should not demand our money so coarsely.

– You freely handed it to my brother.

– That is the point. Freely. Of our volition.

– You want me to wait to be given it.

– Yes.

– You want docility. You want me to appear indifferent to the money.

– Yes.

– And as a reward I am given my share.

– Yes.

– This is shameful.

– You know it is not shameful.

He and Hand barked back and forth for a while, making little headway. When Hand had talked him away from the Zaire plan, the brother became hungry. He thrust his palm between us.

"We have any food?" Hand asked me. From my backpack I produced a granola bar. The brother accepted it, didn't open it, and did not stop talking, talking loudly, at us; he was a machine. We were approaching Mbuu, and he was getting desperate.

"Jesus," I said, "is there any way we can ask him to stop talking?"

Hand turned to him, paused, and held up his hands in a

– You throw me, Denis's brother. You make us sad.

– My job is not to make you happy.

– Your job is to be human. First, be human.

– There is no time for being gentle.

– We disagree.

– You do more harm than good by choosing recipients this way. It cannot be fair.

– How ever is it fair?

– You want the control money provides.

– We want the opposite. We are giving up our control.

– While giving it up you are exercising power. The money is not yours.

– I know this.

– You want its power. However exercised, you want its power.

We were in Mbuu, a dark adobe village. There were no constant lines – everything was moving. The walls were moving, they were human. There were people everywhere and everyone was shifting. The homes were open storefronts. Our headlights flashed over hundreds of people, walking, watching TV – large groups or families visible through glassless windows, all in the open-air storefronts, eating their dinners, drinking at a streetside bar, everyone so close.

We stopped and said goodbye to Denis's brother. He paused in the car, waiting. We stared at him. His eyes spoke.

– You owe me.

– We don't.

– This is wrong.

– It's not wrong.

– You're not sure. You're confused.

– Yes I am confused.

– It's all wrong.

He stepped out and closed the door. We got back on the road, on our way back to Saly for dinner. We hadn't eaten all day.

"I don't feel bad about that," Hand said.

"I hated that fucker."

But nothing else in the world had changed.

It was early evening when we got back to the hotel. A hundred yards from the dining room we could hear the clinking of glasses and forks, the murmur of scores of people. Everything inside was white – the tablecloths, the flowers, the people. Chandeliers.

"Holy shit," said Hand. There were two hundred people seated inside, a just slightly upper-middle-class sort of crowd, older, retirees, the kind you might see at the Orlando Ramada.

We were still in our travel clothes, everywhere stained, and a good portion of the diners were staring. We were dirty and Hand looked like a snowboarder too old for the outfit. His bandanna was now around his neck like a retriever's.

We walked to the buffet and built ziggurats of chicken, rice and fruit on our clean white plates. The spread was impressive: one long table for salads, one for breads, one (particularly spectacular) table for fruits and cakes, and a meat, poultry and fish wing, staffed by three Senegalese men in chef's hats. We sat down next to an older couple, who muttered to each other while glancing our way, and in ten minutes they left, amidst more muttering. A man in white took our drink orders. Desperate and unsure of the rules, we ordered six beers for the table.

"So about the multiverse," I said.

"Oh."

"It's irrelevant. Who cares how many universes or planes there are when they don't intersect?"

Hand had a whole drumstick in his mouth. He removed the bone and it was clean, plasticine. The place was pastel-pink and devoid of joy. There was no laughter, very little movement, countless sunburns. It had more the feel of a Florida nursing home cafeteria, on a Monday.

"Who said they don't intersect?" he asked.

"Do they?"

"I don't know. I haven't read anything about that. But the thing you'd like is that with the multiverse, you have basically every option you want – really, every option you'll ever see or imagine – and one of your selves somewhere has taken that option. Pretty much every life you could lead would conceivably be lived by one of your shadow selves. Maybe even after you die."

He took another drumstick and removed all the meat, the veins, the gristle. He was fucking wretched.

"But it's useless," I said, "if you don't share any consciousness."

"Sure. I know. But then again, maybe we're not dying. If you combine the quantum physics paradigm with the idea of the subjectivity of time, we're basically all alive in a thousand places at once, for a neverending present."

There was one black person eating – he was French, it seemed, sitting with a white woman, apparently his wife. But otherwise the dining room was entirely white and of a strikingly similar caste and appearance.

"Looks like a family reunion," I said.

"The tacky side of the family."

"The thing is, it's basically immortality for atheists," Hand said, "and we don't need to wait for any sort of technology catch-up."

It did sound appealing. Consciousness or not, to be alive, always, somewhere. And what about dreams? That's got to figure in – but what I wanted, really, was every option, simultaneously. Not in some parallel and irrelevant universe, but

A group of six walked in, three men and three women, all white but for one woman, who was black, tall, probably Senegalese.

"Wow," said Hand, staring. She was shocking. Incredible posture, wearing a snug white dress over her astounding skin, lines drawn by the most optimistic and even hand – like the finest machines covered in polished leather. Hand had stopped eating. I stopped eating. Almost every Senegalese woman we'd seen looked like this: genetically flawless, robust, with regal bearing and skin like the smoothest stone.

"Stop staring," I said.

"I won't," Hand said.

Half the dining room was watching. It was too obvious. We were thrown back to some other time or place. Was I imagining this? Everyone was watching this woman, either because she had crossed some understood racial line or simply because – I hoped – she made the rest of us look like trolls.

"She's outstanding," said Hand.,

"She's with them."

"Yeah, but why?"

I had an idea but didn't say it. The people she was with were too unimpressive for her. She was slumming. I could only imagine she'd have some other incentive, and hoped she hadn't been bought.

– What are you doing with these men?

– I have my reasons.

– You need not be with these men. We will help you.

– Your help is not welcome.

– Our help is free of obligation. You must choose us.

"Let's go," I said. "I'm done."

We left, getting a better look at her on the way out – demure but with a smile like the thrusting open of curtains – and we dodged the white spray of the sprinklers on the way back to the room. Hand showered; I called my mom.

"Hello?" It was her on the first ring.

I swallowed my gum. I didn't expect the phone to work, to reach Memphis without an operator. She was in the garden. She'd just come back from a cooking class.

"What day is it there?" I asked.

"Monday, dummy. We're only seven hours behind you."

"Eight, I think."

"Greenland is more like seven, I think."

"Oh, we're not in Greenland."

"You didn't go?"

"We're in Senegal."

"That's right. You told me that."

"Mom. Are you getting too much sun?"

"I'm fine. How is it there? You caught anything yet?"

"Like what? Fish?"

"Just make sure you wear condoms. Six condoms."

"Thanks."

"So how is it?"

"It's good," I said. "So good." I told her what we'd been doing. I went on for a while. She had to stop me.

"I don't need every last minute, hon."

– You do.

"But that's sort of the point," I said.

"What is?"

"The every last minute part. We want you to care."

"I care. I care. How much have you given away so far?"

"I guess about $1,000."

"You're going to have to quicken your pace."

I told her about the basketball game.

"You give any to them?"

"One kid. $300 to him. He was a Bulls fan."

"What about the other kids?" she asked.

"We gave them some water."

"But what about money for them?"

"We couldn't," I said. "We couldn't really spread it out evenly. There were at least fifteen of them." I told her about Denis's brother, who got in the car and who wouldn't stop talking.

"You didn't give him money, I don't suppose."

"No."

"Honey."

"Yes."

"Why not just bring it back here and give it to a charity? There's a place Cathy Wambat works with – they help poor kids get their cleft palates fixed. She would love to -"

"There's a whole charity for cleft palates?"

"Of course."

"But what makes that better than this?"

She sighed and left the line quiet for a minute.

"Don't you think it's all a little condescending?" she said.

"What?"

"You swooping in and -"

"Giving them cash. This is condescending."

"Don't get so angry."

– It's just such a stupid fucking word to use. There's not one morsel of logic to that word, here. It's a defense you use to defend your own inaction.

I sighed an angry sigh.

"Will, who says they want it?"

"They look like they could use it."

"And if not?"

"Then they can give it to someone else."

"Well, see -"

"The point is I don't want it. And we like giving it. It's a way to meet people, if nothing else."

"Well I'm sure you could meet some nice ladies -"

I started whistling, loudly.

"So," she said finally, "how do you decide who gets the money?"

"I don't know. It's random. It's obvious. I don't know."

She laughed loudly, hugely amused. Then sighed. "That's not really fair, is it, Will?"

"Denis's brother was a dick."

She laughed again, at me, without kindness. I couldn't believe I was paying for this kind of aggravation.

"But it's so subjective, dear," she said.

"Of course it's subjective!"

She sighed. I sighed. We waited.

– Tell me there's a better way, Mom.

– I can't. I don't know of one.

"Why are you doing this to me now?" I said.

"I'm only asking questions, hon."

– What are you saying? That we're not allowed to see their faces? You're saying that. You're the type that won't give to a street person; you'll think you're doing them harm. But who's condescending then? You withhold and you run counter to your instincts. There is disparity and our instinct is to create parity, immediately. Our instinct is to split our bank account with the person who has nothing. But you're talking behind seven layers of denial and justification. If it feels good it

"Well," I said, "your questions aren't interesting to me."

"Well, for that I apologize."

"I just think you're overthinking it, Mom."

"I am prone to that sort of thing."

"Oh really? I'd never noti -"

"Bye bye, smart mouth."

She hung up.

Hand dressed and we scuffled back up the road. The sky was a planetarium's half-dome ceiling, full of stars but not dark enough. The trees stood black underneath and against the grey sky, shadowing the dirt road with mean quick scratches. I was pissed. For every good deed there is someone, who is not doing a good deed, who is, for instance, gardening, questioning exactly how you're doing that good deed. For every secretary giving her uneaten half-sandwich to a haggard unwashed homeless vet, there is someone to claim that act is only, somehow,

"What are you muttering about?" Hand asked.

"Nothing." I didn't know I'd been muttering.

"Between that and the talking in your sleep -"

At a snack bar we bought ice cream. The woman at the counter had hair like a backup dancer and was watching dolphins on TV. Hand had an orange push-up approximation and I had a thick tongue of vanilla ice cream covered in chocolate, on a stick. I tore the thin shiny plastic and ate the chocolate first, then the white cold ice cream, so soft in the humid and darkening air, and it ran down my hand and throat at the same time.

As we walked under the infrequent streetlights we had two and three shadows, as one light cast our shadow up and the other down, sometimes overlapping. The lights didn't know what they were doing. The lights knew nothing.

The moon was yellow and ringed with a pale white halo. There were small stones in my shoes. I stopped to empty them, leaning against Hand. When we began walking my shoes filled again.

The area around the resort was crowded with discos and casinos. We went to the main casino first, a small, though plush, one-room affair with two card tables and about thirty slot machines. We recognized about a dozen people from dinner; my face parted the crowd, and they looked at us with tired eyes.

"Check it out," Hand said, pointing a finger at the clientele and casting an infinity symbol over them. "You notice anything about the men here?"

"The sweaters."

"Yeah."

"Jesus."

Every man in the room, almost – there were about twenty men in this casino, most of them young, and twelve of them qualified – was wearing a cotton sweater over his shoulders, tied loosely at the collarbone. Twelve men, and the sweaters were each and all yellow or sky-blue, and always the tying was done with the utmost delicacy. You couldn't, apparently, actually

It hit me, again, that we were here. I'd never been farther than Nevada – with Jack and his family, for fourth-grade spring break, by car. We drove twenty-two hours, each way, leaving about seven in between, spent atop of horses that wanted us dead or in chains. Hand had been to Toronto, which was closer, actually, to Milwaukee, but he didn't see it that way.

There were postcards near the door, not of the ocean but of the resorts on the ocean, and I bought one – the first postcard I'd ever even pretended to plan on sending. If I had someone to write to, a Clementine, I could document this, could shape it into some sense. If I wrote to the twins, even on this napkin here and with this ballpoint pen borrowed from the Senegalese bartender with the birthmark like an Ash Wednesday smudge, they would keep the letters and always know I thought of them -

"That's good so far."

Hand was over my shoulder.

"You really captured it, Will. All those blank spaces, too -"

"Fuck you."

We stood outside in the cooling black night, and wondered if we could do anything extraordinary. If we could live up to our responsibility here: We had traveled 4,200 miles or whatever and thus were obligated to create something. We had to take the available materials and make something worthy.

"You call home yet?" I asked Hand.

"No. You?"

"Yeah."

"Mine won't care. You know them."

I did and I didn't. Hand's father was a tall man who bent over, had been bending to talk to his much-shorter wife for so long that his head seemed permanently tilted, chin in his sternum. With the face of a shovel and the eyes of a wolf, he worked for a law firm but I'm not sure he was a lawyer; he might have been a lawyer but somehow I suspect he was not; he was one of those distant small-eyed men about whom anything could have been possible – molestation, murder, tax evasion, bigamy. Hand's mom was a nurse who worked, for most of our growing up, at the hospital, though later just in one dying man's house, for two years – a grand marble-laden house that became more or less hers, with her own bedroom, her own parking space in the garage, everything.

Which was fine but also wrong, because then Hand had to be jealous of this new home and his mother's effortless way of seeming its matriarch. Hand had two older brothers, much older. I had seen them only a few times each, knew them more from their graduation pictures; for some reason they had graduated on the same day, even though one, I think Steve, the one who was almost crosseyed, was a year older than Eddie, who had Shawn Cassidy hair and eyes that didn't blink and had come up with Hand's nickname – first it was

We decided we'd head into town and find someone's home and walk into it with flowers. It was something we'd talked about doing in the last few years – I have no idea when the idea originated or why. We would knock, we imagined, or maybe come through a back door, the porch, and either way we would bring wine or flowers. It was our firm belief that we could walk into any office or home, anywhere in the world, with flowers, and be taken in. Shock would be softened by blind confusion then affectionate bewilderment, and soon we'd be family.

The road was busy with vacationers walking to Saly's main strip, about three blocks of restaurants, clubs and bars, and the occasional car weaving slowly around the potholes, looking for parking. We bought a small loud bouquet of daisies and violets and something local, red and wet like meat.

Two young girls, barefoot and without saddles, road by on horses the color of gravel. Hand made a gesture indicating he was going to run after them, jump onto a car and from there onto the back of one of the horses. I shook my head vigorously. He pouted.

From a right-leaning building with a second-story balcony, a cat spoke, and we stopped. There were two mailboxes by the doorway and we, with me holding the flowers, gripping too tightly, took it as a sign.

"This is it," I said. "We have to go up."

"And we ring the bell, or what?"

"What time is it?"

"Ten maybe," Hand said. "Is that too late?"

We decided to go up first and survey. The steps took our footsteps, knocks of knuckles against wood, and we were soon at the upper landing, between doors.

"Which one?" Hand asked.

One was ajar. "This one," I said.

With a handle in place of a knob, it looked like a door to another hallway, so we pushed through. But it wasn't a hallway. We were in an apartment. We gave each other looks of alarm. We were in someone's apartment already.

But neither of us made a move to leave.

We took off our shoes, and I set the flowers down atop them. We stepped into the home and closed the door behind us, so quiet it confused me. A large portrait of a man in uniform, a political portrait, hung over the doorway. A table, a dinner table, stood on tip-toes in the middle of the small main room. Four place-settings, the remains of dinner. No sounds yet. The painted walls a faded olive, stained with fingerprints. Pictures torn from magazines pinned to the walls – three or four of professional motorcross riders, and next to them a series of postcards of women in ornate and bulbous Easter outfits. Above them, a large studio picture of a family of four, the family who lived here, we guessed, all wearing soccer uniforms. Hand raised his eyebrows at me as if to say:

The apartment was tight, tidy and empty of anything of objective value. The kitchen was just off the main room, a cramped nook with a blue tile counter. The kitchen gave way to another room, a kind of den, with a couch and a small, upright lawn chair on either side. There was a small mountain of stuffed animals in one corner – Yosemite Sam on top – and a neat row of four plastic soccer balls. A TV pulsed, but without sound.

There was no movement in the house, no noise, but I expected something at any second. A man in a robe with a shotgun. It would almost be a relief.

Hand was across the room already, looking for the bedrooms. There were two doors. He opened one, a closet. His head was then in the other, and quickly he jerked it back. He tiptoed back to me – I was hiding in the kitchen by now – and opened his mouth to speak. I made the angriest face I could, as quickly as I could, to thwart his attempt to talk. He stopped in time, making an elaborate gesture of surrender.