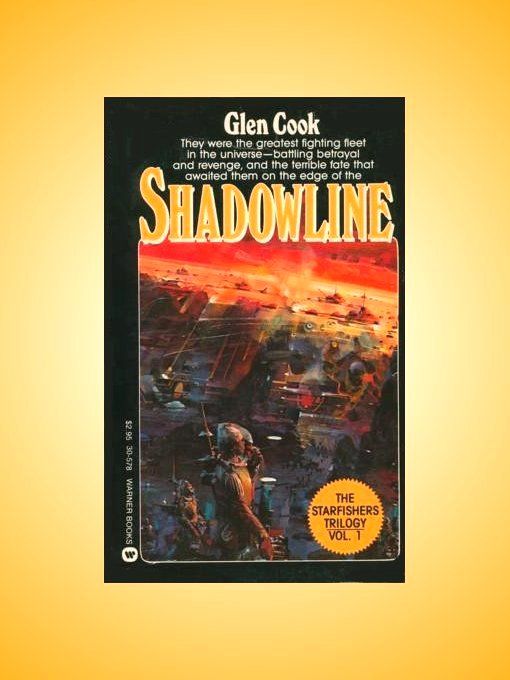

"Shadowline - Starfishers Triology - Book 1" - читать интересную книгу автора (Cook Glen)

|

Glen Cook Shadowline - Starfishers Triology - Book 1

Book One#8212;ROPE

One: 3052 AD

Who am I? What am I?

I am the bastard child of the Shadowline. That jagged rift of sun-broiled stone was my third parent.

You cannot begin to understand me, or the Shadowline, without knowing my father. And to know Gneaus Julius Storm you have to know our family, in all its convolute interpersonal relationships and history. To know our family...

There is no end to this. The ripples spread. And the story, which has the Shadowline and myself at one end, is an immensely long river. It received the waters of scores of apparently insignificant tributary events.

Focusing the lens at its narrowest, my father and Cassius (Colonel Walters) were the men who shaped me most. This is their story. It is also the story of the men whose stamp upon them ultimately shaped their stamp upon me.

#8212;Masato Igarashi Storm

Two: 3031 AD

Deep in the Fortress of Iron, in the iron gloom of his study, Gneaus Storm slouched in a fat, deep chair. His chin rested on his chest. His good eye was closed. Long grey hair cascaded down over his tired face.

The flames in the nearest fireplace leapt and swirled in an endless morisco. Light and shadow played out sinister dramas over priceless carpeting hand-loomed in Old Earth's ancient Orient. The shades of might-have-been played tag among the darkwood beams supporting the stone ceiling.

Storm's study was a stronghold within the greater Fortress. It was the citadel of his soul, the bastion of his heart. Its walls were lined with shelves of rare editions. A flotilla of tables bore both his collectibles and papers belonging to his staff. The occasional silent clerk came and went, updating a report before one of the chairs.

Two Shetland-sized mutant Alsatians prowled the room, sniffing shadows. One rumbled softly deep in its throat. The hunt for an enemy never ended.

Nor was it ever successful. Storm's enemies did not hazard his planetoid home.

A black creature of falcon size flapped into the study. It landed clumsily in front of Storm. Papers scattered, frightening it. An aura of shadow surrounded it momentarily, masking its toy pterodactyl body.

It was a ravenshrike, a nocturnal flying lizard from the swamps of The Broken Wings. Its dark umbra was a psionically generated form of protective coloration.

The ravenshrike cocked one red night eye at its mate, nesting in a rock fissure behind Storm. It stared at its master with the other.

Storm did not respond.

The ravenshrike waited.

Gneaus Julius Storm pictured himself as a man on the downhill side of life, coasting toward its end. He was nearly two hundred years old. The ultimate in medical and rejuvenation technology kept him physically forty-five, but doctors and machines could do nothing to refresh his spirit.

One finger marked his place in an old holy book. It had fallen shut when he had drifted off. "A time to be born and a time to die... "

A youth wearing Navy blacks slipped into the room. He was short and slight, and stood as stiff as a spear. Though he had visited the study countless times, his oriental inscrutability gave way to an expression of awe.

And of his father he thought,

They could not. Not while Richard Hawksblood lived. They did not dare. So someday, as all mercenaries seemed to do, Gneaus Storm would find his last battlefield and his death-without-resurrection.

Storm's tired face rose. It remained square-jawed and strong. Grey hair stirred in a vagrant current from an air vent.

Mouse left quietly, yielding to a moment of deep sadness. His feelings for his father bordered on reverence. He ached because his father was boxed in and hurting.

He went looking for Colonel Walters.

Storm's good eye opened. Grey as his hair, it surveyed the heart of his stateless kingdom. He did not see a golden death mask. He saw a mirror that reflected the secret Storm.

His study contained more than books. One wall boasted a weapons collection, Sumerian bronze standing beside the latest stressglass multi-purpose infantry small arms. Lighted cabinets contained rare china, cut crystal, and silver services. Others contained ancient Wedgwood. Still more held a fortune in old coins within their velvet-lined drawers.

He was intrigued by the ebb and flow of history. He took comfort in surrounding himself with the wrack it left in passing.

He could not himself escape into yesterday. Time slipped through the fingers like old water.

A gust from the cranky air system riffled papers. The banners overhead stirred with the passage of ghosts. Some were old. One had followed the Black Prince to Navarette. Another had fallen at the high-water mark of the charge up Little Round Top. But most represented milemarks in Storm's own career.

Six were identical titan-cloth squares hanging all in a line. Upon them a golden hawk struck left to right down a fall of scarlet raindrops, all on a field of sable. They were dull, unimaginative things compared to the Plantagenet, yet they celebrated the mountaintop days of Storm's Iron Legion.

He had wrested them from his own Henry of Trastamara, Richard Hawksblood, and each victory had given him as little satisfaction as Edward had extracted from Pedro the Cruel.

Richard Hawksblood was the acknowledged master of the mercenary art.

Hawksblood had five Legion banners in a collection of his own. Three times they had fought to a draw.

Storm and Hawksblood were the best of the mercenary captain-kings, the princes of private war the media called "The Robber Barons of the Thirty-First Century." For a decade they had been fighting one another exclusively.

Only Storm and his talented staff could beat Hawksblood. Only Hawksblood had the genius to withstand the Iron Legion.

Hawksblood had caused Storm's bleak mood. His Intelligence people said Richard was considering a commission on Blackworld.

"Let them roast," he muttered. "I'm tired."

But he would fight again. If not this time, then the next. Richard would accept a commission. His potential victim would know that his only chance of salvation was the Iron Legion. He would be a hard man who had clawed his way to the top among a hard breed. He would be accustomed to using mercenaries and assassins. He would look for ways to twist Storm's arm. And he would find them, and apply them relentlessly.

Storm had been through it all before.

He smelled it coming again.

A personal matter had taken him to Corporation Zone, on Old Earth, last month. He had made the party rounds, refreshing his contacts. A couple of middle-management types had approached him, plying him with tenuous hypotheses.

Blackworlders clearly lacked polish. Those apprentice Machiavellis had been obvious and unimpressive, except in their hardness. But their master? Their employer was Blake Mining and Metals Corporation of Edgeward City on Blackworld, they told him blandly.

Gneaus Julius Storm was a powerful man. His private army was better trained, motivated, and equipped than Confederation's remarkable Marines. But his Iron Legion was not just a band of freebooters. It was a diversified holding company with minority interests in scores of major corporations. It did not just fight and live high for a while on its take. Its investments were the long-term security of its people.

The Fortress of Iron stretched tentacles in a thousand directions, though in the world of business and finance it was not a major power. Its interests could be manipulated by anyone with the money and desire.

That was one lever the giants used to get their way.

In the past they had manipulated his personal conflicts with Richard Hawkblood, playing to his vanity and hatred. But he had outgrown his susceptibility to emotional extortion.

"It'll be something unique this time," he whispered.

Vainly, he strove to think of a way to outmaneuver someone he did not yet know, someone whose intentions were not yet clear.

He ignored the flying lizard. It waited patiently, accustomed to his brooding way.

Storm took an ancient clarinet from a case lying beside his chair. He examined the reed, wet it. He began playing a piece not five men alive could have recognized.

He had come across the sheet music in a junk shop during his Old Earth visit. The title, "Stranger on the Shore," had caught his imagination. It fit so well. He felt like a stranger on the shore of time, born a millennium and a half out of his natural era. He belonged more properly to the age of Knollys and Hawkwood.

The lonely, haunting melody set his spirit free. Even with his family, with friends, or in crowds, Gneaus Storm felt set apart, outside. He was comfortable only when sequestered here in his study, surrounded by the things with which he had constructed a stronghold of the soul.

Yet he could not be without people. He had to have them there, in the Fortress, potentially available, or he felt even more alone.

His clarinet never left his side. It was a fetish, an amulet with miraculous powers. He treasured it more than the closest member of his staff. Paired with the other talisman he always bore, an ancient handgun, it held the long night of the soul at bay.

Gloomy. Young-old. Devoted to the ancient, the rare, the forgotten. Cursed with a power he no longer wanted. That was a first approximation of Gneaus Julius Storm.

The power was like some mythological cloak that could not be shed. The more he tried to slough it, the tighter it clung and the heavier it grew. There were just two ways to shed it forever.

Each required a death. One was his own. The other was Richard Hawksblood's.

Once, Hawksblood's death had been his life's goal. A century of futility had passed. It no longer seemed to matter as much.

Storm's heaven, if ever he attained it, would be a quiet, scholarly place that had an opening for a knowledgeable amateur antiquarian.

The ravenshrike spread its wings momentarily.

Three: 3052 AD

Can we understand a man without knowing his enemies? Can we know yin without knowing yang? My father would say no. He would say if you want to see new vistas of Truth, go question the man who wants to kill you.

A man lives. When he is young he has more friends than he can count. He ages. The circle narrows. It turns inward, becoming more closed. We spend our middle and later years doing the same things with the same few friends. Seldom do we admit new faces to the clique.

But we never stop making enemies.

They are like dragon's teeth flung wildly about us as we trudge along the paths of our lives. They spring up everywhere, unwanted, unexpected, sometimes unseen and unknown. Sometimes we make or inherit them simply by being who or what we are.

My father was an old, old man. He was his father's son.

His enemies were legion. He never knew how many and who they were.

#8212;Masato Igarashi Storm

Four: 2844 AD

The building was high and huge and greenhouse-hot. The humidity and stench were punishing. The polarized glassteel roof had been set to allow the maximum passage of sunlight. The air conditioning was off. The buckets of night earth had not been removed from the breeding stalls.

Norbon w'Deeth leaned on a slick brass rail, scanning the enclosed acres below the observation platform.

Movable partitions divided the floor into hundreds of tiny cubicles rowed back to back and facing narrow passageways. Each cubicle contained an attractive female. There were so many of them that their breathing and little movements kept the air alive with a restless susurrus.

Deeth was frightened but curious. He had not expected the breeding pens to be so huge.

His father's hand touched his shoulder lightly, withdrew to flutter in his interrogation of his breeding master. The elder Norbon carried half a conversation with his hands.

"How can they refuse? Rhafu, they're just animals."

Deeth's thoughts echoed his father's. The Norbon Head could not be wrong. Rhafu had to be mistaken. Breeding and feeding were the only things that interested animals.

"You don't understand, sir." Old Rhafu's tone betrayed stress. Even Deeth sensed his frustration at his inability to impress the Norbon with the gravity of the situation. "It's not entirely that they're refusing, either. They're just not interested. It's the boars, sir. If it were just the sows the boars would take them whether or not they were willing."

Deeth looked up at Rhafu. He was fond of the old man. Rhafu was the kind of man he wished his father were. He was the old adventurer every boy hoped to become.

The responsibilities of a Family Head left little time for close relationships. Deeth's father was a remote, often harried man. He seldom gave his son the attention he craved.

Rhafu was a rogue full of stories about an exciting past. He proudly wore scars won on the human worlds. And he had time to share his stories with a boy.

Deeth was determined to emulate Rhafu. He would have his own adventures before his father passed the family into his hands. His raidships would plunder Terra, Toke, and Ulant. He would return with his own treasury of stories, wealth, and honorable scars.

It was just a daydream. At seven he already knew that heirs-apparent never risked themselves in the field. Adventures were for younger sons seeking an independent fortune, for daughters unable to make beneficial alliances, and for possessionless men like Rhafu. His own inescapable fate was to become a merchant prince like his father, far removed from the more brutal means of accumulating wealth. The only dangers he would face would be those of inter-Family intrigues over markets, resources, and power.

"Did you try drugs?" his father asked. Deeth yanked himself back to the here and now. He was supposed to be learning. His father would smack him a good one if his daydreaming became obvious.

"Of course. Brood sows are always drugged. It makes them receptive and keeps their intellection to a minimum."

Rhafu was exasperated. His employer had not visited Prefactlas Station for years. Moreover, the man confessed that he knew nothing about the practical aspects of slave breeding. Fate had brought him here in the midst of a crisis, and he persisted in asking questions which cast doubt on the competence of the professionals on the scene.

"We experimented with aphrodisiacs. We didn't have much luck. We got more response when we butchered a few boars for not performing, but when we watched them closer we saw they were withdrawing before ejaculation. Sir, you're looking in the wrong place for answers. Go poke around outside the station boundary. The animals wouldn't refuse if they weren't under some external influence."

"Wild ones?" The Norbon shrugged, dismissing the idea. "What about artificial insemination? We don't dare get behind. We've got contracts to meet."

This was why the Norbon was in an unreasonable mood. The crisis threatened the growth of the Norbon profit curve.

Deeth turned back to the pens. Funny. The animals looked so much like Sangaree. But they were filthy. They stank.

Rhafu said some of the wild ones were different, that they cared for themselves as well as did people. And the ones the Family kept at home, at the manor, were clean and efficient and indistinguishable from real people.

He spotted a sow that looked like his cousin Marjo. What would happen if a Sangaree woman got mixed in with the animals? Could anyone pick her out? Aliens like the Toke and Ulantonid were easy, but these humans could pass as people.

"Yes. Of course. But we're not set up to handle it on the necessary scale. We've never had to do it. I've had instruments and equipment on order since the trouble started."

"You haven't got anything you can make do with?" Deeth's father sounded peevish. He became irritable when the business ran rocky. "There's a fortune in the Osirian orders, and barely time to push them through the fast-growth labs. Rhafu, I can't default on a full-spectrum order. I won't. I refuse."

Deeth smiled at a dull-eyed sow who was watching him half-curiously. He made a small, barely understood obscene gesture he had picked up at school.

"Ouch!"

Having disciplined his son, the Norbon turned to Rhafu as though nothing had happened. Deeth rubbed the sting away. His father abhorred the thought of coupling with livestock. To him that was the ultimate perversion, though the practice was common. The Sexon Family maintained a harem of specially bred exotics.

"Thirty units for the first shipment," Rhafu said thoughtfully. "I think I can manage that. I might damage a few head forcing it, though."

"Do what you have to."

"I hate to injure prime stock, sir. But there'll be no production otherwise. We've had to be alert to prevent self-induced abortion."

"That bad? It's really that bad?" Pained surprise flashed across the usually expressionless features of the Norbon. "That does it. You have my complete sanction. Do what's necessary. These contracts are worth the risk. They're going to generate follow-ups. The Osirian market is wide open. Fresh. Untouched. The native princes are total despots. Completely sybaritic and self-indulgent. It's one of the human First Expansion worlds gone feral. They've devolved socially and technologically to a feudal level."

Rhafu nodded. Like most Sangaree with field experience, he had a solid background in human social and cultural history.

The elder Norbon stared into the pens that were the cornerstone of the Family wealth. "Rhafu, Osiris is the Norbon Wholar. Help me exploit it the way a Great House should."

Deeth was not sure he wanted an El Dorado for the Norbon. Too much work for him when he became Head. And he would have to socialize with those snobbish Krimnins and Sexons and Masons. Unless he could devour the dream and make the Norbon the richest Family of all. Then he would be First Family Head, could do as he pleased, and would not have to worry about getting along.

"It's outside trouble, I swear it," Rhafu said. "Sir, there's something coming on. Even the trainees in Isolation are infected. They've been complaining all week. Station master tells me it's the same everywhere. Agriculture caught some boar pickers trying to fire the sithlac fields."

"Omens and signs, Rhafu? You're superstitious? They are the ones who need the supernatural. It's got to be their water. Or feed."

"No. I've checked. Complete chemical analysis. Everything is exactly what it should be. I tell you, something's happening and they know it. I've seen it before, remember. On Copper Island."

Deeth became interested again. Rhafu had come to the Norbon from the Dathegon, whose station had been on Copper Island. No one had told him why. "What happened, Rhafu?"

The breeding master glanced at his employer. The Norbon frowned, but nodded.

"Slaves rising, Deeth. Because of sloppy security. The field animals came in contact with wild ones. Pretty soon they rebelled. Some of us saw it coming. We tried to warn the station master. He wouldn't listen. Those of us who survived work for your father now. The Dathegon never recovered."

"Oh."

"And you think that could happen here?" Deeth's father demanded.

"Not necessarily. Our security is better. Our station master served in human space. He knows what the animals can do when they work together. I'm just telling you what it looks like, hoping you'll take steps. We'll want to hold down our losses."

Rhafu was full of the curious ambivalence of Sangaree who had served in human space. Individuals and small groups he called animals. Larger bodies he elevated to slave status. When he mentioned humanity outside Sangaree dominion he simply called them humans, degrading them very little. His own discriminations reflected those of his species as to the race they exploited.

"If we let it go much longer we'll have to slaughter our best stock to stop it."

"Rhafu," Deeth asked, "what happened to the animals on Copper Island?"

"The Prefactlas Heads voted plagues."

"Oh." Deeth tried not to care about dead animals. Feeling came anyway. He was not old enough to have hardened. If only they did not look so much like real people...

"I'll think about what you've told me, Rhafu." The Norbon's hand settled onto Deeth's shoulder again. "Department Heads meeting in the morning. We'll determine a policy then. Come, Deeth."

They inspected the sithlac in its vast, hermetically sealed greenhouse. The crop was sprouting. In time the virally infected germ plasm of the grain would be refined to produce stardust, the most addictive and deadly narcotic ever to plague humankind.

Stardust addicts did not survive long, but while they did they provided their Sangaree suppliers with a guaranteed income.

Sithlac was the base of wealth for many of the smaller Families. It underpinned the economy of the race. And it was one of the roots of their belief in the essential animal-ness of humanity. No true sentient would willingly subject itself to such a degrading, slow, painful form of suicide.

Deeth fidgeted, bored, scarcely hearing his father's remarks. He was indifferent to the security that a sound, conservative agricultural program represented. He was too young to comprehend adult needs. He preferred the risk and romance of a Rhafu-like life to the security of drug production.

Rhafu had not been much older than he was now when he had served as a gunner's helper during a raid into the Ulant sphere.

Raiding was the only way possessionless Sangaree had to accumulate the wealth needed to establish a Family. Financially troubled Families sometimes raided when they needed a quick cash flow. Most Sangaree heroes and historical figures came out of the raiding.

A conservative, the Norbon possessed no raidships. His transports were lightly armed so his ships' masters would not be tempted to indulge in free-lance piracy.

The Norbon were a "made" Family. They were solid in pleasure slaves and stardust. That their original fortune had been made raiding was irrelevant. Money, as it aged, always became more conservative and respectable.

Deeth reaffirmed his intention of building raiders when he became Head. Everybody was saying that the human and Ulantonid spheres were going to collide soon. That might mean war. Alien races went to their guns when living space and resources were at stake. The period of adjustment and accommodation would be a raidmaster's godsend.

Norbon w'Deeth, Scourge of the Spaceways, was slammed back to reality by the impact of his father's hand. "Deeth! Wake up, boy! Time to go back to the greathouse. Your mother wants us to get ready."

Deeth took his father's hand and allowed himself to be led from the dome. He was not pleased about going. Even prosaic sithlac fields were preferable to parties.

His mother had one planned for that evening. Everyone who was anyone among the Prefactlas Families would be there#8212;including a few fellow heirs-apparent who could be counted on to start a squabble when their elders were not around. He might have to take a beating in defense of Family honor.

He understood that his mother felt obligated to have these affairs. They helped reduce friction between the Families. But why couldn't he stay in his suite and view his books about the great raiders and sales agents? Or even just study?

He was not going to marry a woman who threw parties. They were boring. The adults got staggering around drunk and bellicose, or syrupy, pulling him onto their laps and telling him what a wonderful little boy he was, repelling him with their alcohol-laden breath.

He would never drink, either. A raidmaster had to keep a clear head.

Five: 3052 AD

My father once said that people are a lot like billiard balls and gas molecules. They collide with one another randomly, imparting unexpected angles of momentum. A secondary impact can cause a tertiary, and so forth. With people it's usually impossible to determine an initiator because human relationships try to ignore the laws of thermodynamics. In the case of the Shadowline, though, we can trace everything to a man called Frog.

My father said Frog was like a screaming cue ball on the break. The people-balls were all on the table. Frog's impact set them flying from bank to bank.

My father never met Frog. It's doubtful that Frog ever heard of my father. So it goes sometimes.

#8212;Masato Igarashi Storm

Six: 3007 AD

BLACKWORLD (Reference:

Seven: 3020 AD

Blackworld as a reference-book entry was hardly an eyebrow-raiser. Nothing more than a note to make people wonder why anyone would live there.

It was a hell of a world. Even the natives sometimes wondered why anybody lived there.

Or so Frog thought as he cursed heaven and hell and slammed his portside tracks into reverse.

"Goddamned heat erosion in the friggin' Whitlandsund now," he muttered, and with his free hand returned the gesture of the obelisk/landmark he called Big Dick.

He had become lax. He had been daydreaming down a familiar route. He had aligned Big Dick wrong and drifted into terrain not recharted since last the sun had shoved a blazing finger into the pass.

Luckily, he had been in no hurry. The first sliding crunch under the starboard lead track had alerted him. Quick braking and a little rocking pulled the tractor out.

He heaved a sigh of relief.

There wasn't much real danger this side of the Edge of the World. Other tractors could reach him in the darkness.

He was sweating anyway. For him it did not matter where the accident happened. His finances allowed no margin for error. One screw-up and he was as good as dead.

There was no excuse for what had happened, Brightside or Dark. He was angry. "You don't get old making mistakes, idiot," he snarled at the image reflected in the visual plate in front of him.

Frog was old. Nobody knew just how old, and he wasn't telling, but there were men in Edgeward who had heard him spin tavern tales of his father's adventures with the Devil's Guard, and the Guard had folded a century ago, right after the Ulantonid War. The conservatives figured him for his early seventies. He had been the town character for as long as anyone could remember.

Frog was the last of a breed that had begun disappearing when postwar resumption of commerce had created a huge demand for Blackworld metals. The need for efficiency had made the appearance of big exploitation corporation inevitable. Frog was Edgeward City's only surviving independent prospector.

In the old days, while the Blakes had been on the rise, he had faced more danger in Edgeward itself than he had Brightside. The consolidation of Blake Mining and Metals had not been a gentle process. Now his competition was so insubstantial that the Corporation ignored it. Blake helped keep him rolling, in fact, the way historical societies keep old homes standing. He was a piece of yesterday to show off to out-of-towners.

Frog did not care. He just lived on, cursing everyone in general and Blake in particular, and kept doing what he knew best.

He was the finest tractor hog ever to work the Shadowline. And they damned well knew it.

Still, making it as a loner in a corporate age was difficult and dangerous. Blake had long since squatted on every easily reached pool and deposit Brightside. To make his hauls Frog had to do a long run up the Shadowline, three days or more out, then make little exploratory dashes into sunlight till he found something worthwhile. He would fill his tanks, turn around, and claw his way back home. Usually he brought in just enough to finance maintenance, a little beer, and his next trip out.

If asked he could not have explained why he went on. Life just seemed to pull him along, a ritual of repetitive days and nights that at least afforded him the security of null-change.

Frog eased around the heat erosion on ground that had never been out of shadow, moved a few kilometers forward, then turned into a side canyon where Brightside gases collected and froze into snows. He met an outbound Blake convoy. They greeted him with flashing running lights. He responded, and with no real feeling muttered, "Sons of bitches."

They were just tractor hogs themselves. They did not make policy.

He had to hand load the snow he would ionize in his heat-exchange system. He had to save credit where he could. So what if Corporation tractors used automatic loaders? He had his freedom. He had that little extra credit at boozing time. A loading fee would have creamed it off his narrow profit margin.

When he finished shoveling he decided to power down and sleep. He was not as young as he used to be. He could not do the Thunder Mountains and the sprints to the Shadowline in one haul anymore.

Day was a fiction Blackworlders adjusted to their personal rhythms. Frog's came quickly. He seldom wasted time meeting the demands of his flesh. He wanted that time to meet the demands of his soul, though he could not identify them as such. He knew when he was content. He knew when he was not. Getting things accomplished led to the former. Discontent and impatience arose when he had to waste time sleeping or eating. Or when he had to deal with other people.

He was a born misanthrope. He knew few people that he liked. Most were selfish, rude, and boring. That he might fit a similar mold himself he accepted. He did others the courtesy of not intruding on their lives.

In truth, though he could admit it only in the dark hours, when he could not sleep, he was frightened of people. He simply did not know how to relate.

Women terrified him. He did not comprehend them at all. But no matter. He was what he was, was too old to change, and was content with himself more often than not. To have made an accommodation with the universe, no matter how bizarre, seemed a worthy accomplishment.

His rig was small and antiquated. It was a flat, jointed monstrosity two hundred meters long. Every working arm, sensor housing, antenna, and field-projector grid had a mirror finish. There were scores. They made the machine look like some huge, fantastically complicated alien millipede. It was divided into articulated sections, each of which had its own engines. Power and control came from Frog's command section. All but that command unit were transport and working slaves that could be abandoned if necessary.

Once, Frog had been forced to drop a slave. His computer had erred. It had not kept the tracks of his tail slave locked into the path of those ahead. He had howled and cursed like a man who had just lost his first-born baby.

The abandoned section was now a slag-heap landmark far out the Shadowline. Blake respected it as the tacit benchmark delineating the frontier between its own and Frog's territory. Frog made a point of looking it over every trip out.

No dropped slave lasted long Brightside. That old devil sun rendered them down quick. He studied his lost child to remind himself what became of the careless.

His rig had been designed to operate in sustained temperatures which often exceeded 2000#176; K. Its cooling systems were the most ingenious ever devised. A thick skin of flexible molybdenum/ceramic sponge mounted on a honeycomb-network radiator frame of molybdenum-base alloy shielded the crawler's guts. High-pressure coolants circulated through the skin sponge.

Over the mirrored surface of the skin, when the crawler hit daylight, would lie the first line of protection, the magnetic screens. Ionized gases would circulate beneath them. A molecular sorter would vent a thin stream of the highest energy particles aft. The solar wind would blow the ions over Darkside where they would freeze out and maybe someday ride a crawler Brightside once again.

A crawler in sunlight, when viewed from sunward through the proper filters, looked like a long, low, coruscating comet. The rig itself remained completely concealed by its gaseous chrysalis.

The magnetic screens not only contained the ion shell, they deflected the gouts of charged particles erupting from Blackworld's pre-nova sun.

All that technology and still a tractor got godawful hot inside. Tractor hogs had to encase themselves in life-support suits as bulky and cumbersome as man's first primitive spacesuits.

Frog's heat-exchange systems were energy-expensive, powerful, and supremely effective#8212;and still inadequate against direct sunlight for any extended time. Blackworld's star-sun was just too close and overpoweringly hot.

Frog warmed his comm laser. Only high-energy beams could punch through the solar static. He tripped switches. His screens and heat evacuators powered up. His companion of decades grumbled and gurgled to itself. It was a soothing mix, a homey vibration, the wakening from sleep of an old friend. He felt better when it surrounded him.

In his crawler he was alive, he was real, as much a man as anyone on Blackworld. More. He had beaten Brightside more often than any five men alive.

A finger stabbed the comm board. His beam caressed a peak in the Shadowline, locked on an automatic transponder. "This here's Frog. I'm at the jump-off. Give me a shade crossing, you plastic bastards." He chuckled.

Signals pulsed along laser beams. Somewhere a machine examined his credit balance, made a transfer in favor of Blake Mining and Metals. A green okay flashed across Frog's comm screen.

"Damned right I be okay," he muttered. "Ain't going to get me that easy."

The little man would not pay Blake to load his ionization charge while his old muscles still worked. But he would not skimp on safety Brightside.

In the old days they had had to make the run from the Edge of the World to the Shadowline in sunlight. Frog had done it a thousand times. Then Blake had come up with a way to beat that strait of devil sun. Frog was not shy about using it. He was cheap and independent, but not foolhardy.

The tractor idled, grumbling to itself. Frog watched the sun-seared plain. Slowly, slowly, it darkened. He fed power to his tracks and cooling systems and eased into the shadow of a dust cloud being thrown kilometers high by blowers at the Blake outstation at the foot of the Shadowline. His computer maintained its communion with the Corporation navigator there, studying everything other rigs had reported since its last crossing, continuously reading back data from its own instruments.

The crossing would be a cakewalk. The regular route, highway hard and smooth with use, was open and safe.

Frog's little eyes darted. Banks of screens and lights and gauges surrounded him. He read them as if he were part of the computer himself.

A few screens showed exterior views in directions away from the low sun, the light of which was almost unalterable. The rest showed schematics of information retrieved by laser radar and sonic sensors in his track units. The big round screen directly before him represented a view from zenith of his rig and the terrain for a kilometer around. It was a lively, colorful display. Contour lines were blue. Inherent heats showed up in shades of red. Metal deposits came in green, though here, where the deposits were played out, there was little green to be seen.

The instruments advised him of the health of his slave sections, his reactor status, his gas stores level, and kept close watch on his life-support systems.

Frog's rig was old and relatively simple#8212;yet it was immensely complex. Corporation rigs carried crews of two or three, and backup personnel on longer journeys. But there was not a man alive with whom Frog would have, or could have, stood being sealed in a crawler.

Once certain his rig would take Brightside this one more time, Frog indulged in a grumble. "Should have tacked on to a convoy," he muttered. "Could have prorated the damned shade. Only who the hell has time to wait around till Blake decides to send his suckies out?"

His jointed leviathan grumbled like an earthquake in childbirth. He put on speed till he reached his maximum twelve kilometers per hour. The sonics reached out, listening for the return of ground-sound generated by the crawler's clawing tracks, giving the computer a detailed portrait of nearby terrain conditions. The crossing to the Shadowline was a minimum three-hour run, and with no atmosphere to hold the shadowing dust aloft every second of shade cost. He did not dawdle.

It was another eventless crossing. He hit the end of the Shadowline and instantly messaged Blake to secure shade, then idled down to rest. "Got away with it again, you old sumbitch," he muttered at himself as he leaned back and closed his eyes.

He had to do some hard thinking about this run.

Eight: 3031 AD

Storm placed the clarinet in its case. He faced the creature on his desk, slowly leaned till its forehead touched his own.

His movement was cautious. A ravenshrike could be as worshipful as a puppy one moment, all talons and temper the next. They were terribly sensitive to moods.

Storm never had been attacked by his "pets." Nor had his followers ever betrayed him though sometimes they stretched their loyalties in their devotion.

Storm had weighed the usefulness of ravenshrikes against their unpredictability with care. He had opted for the risk.

Their brains were eidetically retentive for an hour. He could tap that memory telepathically by touching foreheads. Memorization and telepathy seemed to be part of the creatures' shadow adaption.

The ravenshrikes prowled the Fortress constantly. Unaware of their abilities, Storm's people hid nothing from them. The creatures kept him informed more effectively than any system of bugs.

He had acquired them during his meeting with Richard Hawksblood on The Broken Wings. Since, his people had viewed his awareness with almost superstitious awe. He encouraged the reaction. The Legion was an extension of himself, his will in action. He wanted it to move like a part of him.

Aware though he might be, some of his people refused to stop doing the things that made the lizards necessary.

He never feared outright betrayal. His followers owed him their lives. They served with a loyalty so absolute it bordered on the fanatic. But they were wont to do things for his own good.

In two hundred years he had come to an armistice with the perversities of human nature. Every man considered himself the final authority on universe management. It was an inalterable consequence of anthropoid evolution.

Storm corrected them quietly. He was not a man of sound and fury. A hint of disapproval, he had found, achieved better results than the most bitter recrimination.

Images and dialogue flooded his mind as he discharged the ravenshrike's brain-store. From the maelstrom he selected the bits that interested him.

"Oh, damn! They're at it again."

He had suspected as much. He had recognized the signs. His sons Benjamin, Homer, and Lucifer, were forever conspiring to save the old man from his follies. Why couldn't they learn? Why couldn't they be like Thurston, his oldest? Thurston was not bright, but he stuck with the paternal program.

Better, why couldn't they be like Masato, his youngest? Mouse was not just bright, he understood. Probably better than anyone else in the family.

Today his boys were protecting him from what they believed was his biggest weakness. In his more bitter moments he was inclined to agree. His life would be safer, smoother, and richer if he were to assume a more pragmatic attitude toward Michael Dee.

"Michael, Michael, I've had enemies who were better brothers than you are."

He opened a desk drawer and stabbed a button. The summons traveled throughout the Fortress of Iron. While awaiting Cassius's response he returned to his clarinet and "Stranger on the Shore."

Nine: 3031 AD

Mouse stepped into Colonel Walters's office. "The Colonel in?" he asked the orderly.

"Yes, sir. You wanted to see him?"

"If he isn't busy."

The orderly spoke into a comm. "Masato Storm to see you, Colonel." To Mouse, "Go on in, sir."

Mouse stepped into the spartan room that served Thaddeus Immanuel Walters as office and refuge. It was almost as barren as his father's study was cluttered.

The Colonel was down on his knees with his back to the door, eyes at tabletop level, watching a little plastic dump truck scoot around a plastic track. The toy would dump a load of marbles, then scoot back and, through a complicated series of steps, reload the marbles and start over. The Colonel used a tiny screwdriver to probe the device that lifted the marbles for reloading. Two of the marbles had not gone up. "Mouse?"

"In the flesh."

"When did you get in?"

"Last night. Late."

"Seen your father yet?" Walters shimmed the lifter with the screwdriver blade. It did no good.

"I was just down there. Looked like he was in one of his moods. I didn't bother him."

"He is. Something's up. He smells it."

"What's that?"

"Not sure yet. Damn! You'd think they'd have built these things so you could fix them." He dropped the screwdriver and rose.

Walters was decades older than Gneaus Storm. He was thin, dark, cold of expression, aquiline, narrow of eye. He had been born Thaddeus Immanuel Walters, but his friends called him Cassius. He had received the nickname in his plebe year at Academy, for his supposed "lean and hungry look."

He was a disturbing man. He had an intense, snakelike stare. Mouse had known him all his life and still was not comfortable with him.

Cassius had only one hand, his left. The other he had lost long ago, to Fearchild Dee, the son of Michael Dee, when he and Gneaus had been involved in an operation on a world otherwise unmemorable. Like Storm, he refused to have his handicaps surgically rectified. He claimed they reminded him to be careful.

Cassius had been with the Legion since its inception, before Gneaus's birth, on a world called Prefactlas.

"Why did you want me to come home?" Mouse asked. "Your message scared the hell out of me. Then I get here and find out everything's almost normal."

"Normalcy is an illusion. Especially here. Especially now."

Mouse shuddered. Cassius spoke without inflection. He had lost his natural larynx to a Ulantonid bullet on Sierra. His prosthesis had just the one deep, burring tone, like that of a primitive talking computer.

"We feel the forces gathering. When you get as old as we are you can smell it in the ether."

Cassius did something with his toy, then turned to Mouse. His hand shot out.

The blow could have killed. Mouse slid away, crouched, prepared to defend himself.

Cassius's smile was a thin thing that looked alien on his narrow, pale lips. "You're good."

Mouse smiled back. "I keep in practice. I've put in for Intelligence. What do you think?"

"You'll do. You're your father's son. I'm sorry I missed you last time I was in Luna Command. I wanted to introduce you to some people."

"I was in the Crab Nebula. A sunjammer race. My partner and I won it. Even beat a Starfisher crew. And they know the starwinds like fish know their rivers. They'd won four regattas running." Mouse was justifiably proud of his accomplishment. Starfishers were all but invincible at their own games.

"I heard the talk. Congratulations."

Cassius was the Legion's theoretical tactician as well as its second in command and its master's confidant. Some said he knew more about the art of war than anyone living, Gneaus Storm and Richard Hawksblood notwithstanding. War College in Luna Command employed him occasionally, on a fee lecture basis, to chair seminars. Storm's weakest campaigns had been fought when Cassius had been unable to assist him. Hawksblood had beaten their combined talents only once.

A buzzer sounded. Cassius glanced at a winking light. "That's your father. Let's go."

Ten: 3020 AD

The Shadowline was Blackworld's best-known natural feature. It was a four-thousand-kilometer-long fault in the planet's Brightside crust, the sunward side of which had heaved itself up an average of two hundred meters above the burning plain. The rift wandered in a northwesterly direction. It cast a permanent wide band of shadow that Edgeward's miners used as a sun-free highway to the riches of Brightside. By extending its miners' scope of operations the Shadowline gave Edgeward a tremendous advantage over competitors.

No one had ever tried reaching the Shadowline's end. There was no need. Sufficient deposits lay within reach of the first few hundred kilometers of shade. The pragmatic miners shunned a risk that promised no reward but a sense of accomplishment.

On Blackworld a man did not break trail unless forced by a pressing survival need.

But that rickety little man called Frog, this time, was bound for the Shadowline's end.

Every tractor hog considered it. Every man at some time, off-handedly, contemplates suicide. Frog was no different. This was a way to make it into the histories. There were not many firsts to be claimed on Blackworld.

Frog had been thinking about it for a long time. He usually sniggered at himself when he did. Only a fool would try it, and old Frog was no fool.

Lately he had become all too aware of his age and mortality. He had begun to dwell on the fact that he had done nothing to scratch his immortality on the future. His passing would go virtually unnoticed. Few would mourn him.

He knew only one way of life, hogging, and there was only one way for a tractor hog to achieve immortality. By ending the Shadowline.

He still had not made up his mind. Not absolutely. The rational, experienced hog in him was fighting a vigorous rearguard action.

Though Torquemada himself could not have pried the truth loose, Frog wanted to impress someone.

Humanity in the whole meant nothing to Frog. He had been the butt of jests and cruelties and, worse, indifference all his life. People were irrelevant. There was only one person about whom he cared.

He had an adopted daughter named Moira. She was a white girl-child he had found wandering Edgeward's rudimentary spaceport. She had been abandoned by Sangaree slavers passing through hurriedly, hotly pursued by Navy and dumping evidence wherever they could. She had been about six, starving, and unable to cope with a non-slave environment. No one had cared. Not till the hard-shelled, bullheaded, misanthropic dwarf, Edgeward's involuntary clown laureate, had happened along and been touched.

Moira was not his first project. He was a sucker for strays.

He had cut up a candyman pervert, then had taken her home, as frightened as a newly weaned kitten, to his tiny apartment-lair behind the water plant down in Edgeward's Service Underground.

The child complicated his life no end, but he had invested his secret self in her. Now, obsessed with his own mortality, he wanted to leave her with memories of a man who had amounted to more than megaliters of suit-sweat and a stubborn pride five times too big for his retarded growth.

Frog wakened still unsure what he would do. The deepest route controls that he himself had set on previous penetrations ran only a thousand kilometers up the Shadowline.

That first quarter of the way would be the easy part. The markers would guide his computers and leave him free to work or loaf for the four full days needed to reach the last transponder. Then he would have to go on manual and begin breaking new ground, planting markers to guide his return. He would have to stop to sleep. He would use up time backing down to experiment with various routes. Three thousand kilometers might take forever.

They took him thirty-one days and a few hours. During that time Frog committed every sin known to the tractor hog but that of getting himself killed. And Death was back there in the shadows, grinning, playing a little waiting game, keeping him wondering when the meathook would lash out and yank him off the stage of life.

Frog knew he was not going to make it back.

No rig, not even the Corporation's newest, had been designed to stay out this long. His antique could not survive another four thousand clicks of punishment.

Even if he had perfect mechanical luck he would come up short on oxygen. His systems were not renewing properly.

He had paused when his tanks had dropped to half, and had thought hard. And then he had gone on, betting his life that he could get far enough back to be rescued with proof of his accomplishment.

Frog was a poker player. He made the big bets without batting an eye.

He celebrated success by breaking his own most inflexible rule. He shed his hotsuit.

A man out of suit stood zero chance of surviving even minor tractor damage. But he had been trapped in that damned thing, smelling himself, for what seemed half a lifetime. He had to get out or start screaming.

He reveled in the perilous, delicious freedom. He even wasted water scouring himself and the suit's interior. Then he went to work on the case of beer some damn fool part of him had compelled him to stash in his tool locker.

Halfway through the case he commed Blake and crowed his victory. He gave the boys at the shade station several choruses of his finest shower-rattlers. They did not have much to say. He fell asleep before he could finish the case.

Sanity returned with his awakening.

"Goddamn, you stupid old man. What the hell you doing, hey? Nine kinds of fool in one, that what you are." He scrambled into his suit. "Oh, Frog, Frog. You don't got to prove you crazy. Man, they already know."

He settled into his control couch. It was time to resume his daily argument, via the transponder-markers, with the controller at the Blake outstation. "Sumbitch," he muttered. "Bastard going to eat crow today. Made a liar of him, you did, Frog."

Was anybody else listening? Anybody in Edgeward? It seemed likely. The whole town would know by now. The old man had finally gone and proved that he was as crazy as they always thought.

It would be a big vicarious adventure for them, especially while he was clawing his way back with his telemetry reporting his sinking oxygen levels. How much would get bet on his making it? How much more would be put down the other way?

"Yeah," he murmured. "They be watching." That made him feel taller, handsomer, richer, more macho. For once he was a little more than the town character.

But Moira... His spirits sank. The poor girl would be going through hell.

He did not open comm right away. Instead, he stared at displays for which he had had no time the night before. He had become trapped in a spider's web of fantasy come true.

From the root of the Shadowline hither he had seen little but ebony cliffs on his left and flaming Brightside on his right. Every kilometer had been exactly like the last and next. He had not found the El Dorado they had all believed in back in the old days, when they had all been entrepreneur prospectors racing one another to the better deposits. After the first thousand virgin kilometers he had stopped watching for the mother lode.

Even here the immediate perception remained the same, except that the contour lines of the rift spread out till they became lost in those of the hell plain beyond the Shadowline's end. But there was one eye-catcher on his main display, a yellowness that grew more intense as the eye moved to examine the feedback on the territory ahead.

Near his equipment's reliable sensory limits it became a flaming intense orange.

Yellow. Radioactivity. Shading to orange meant there was so much of it that it was generating heat. He glared at the big screen. He was over the edge of the stain, taking an exposure through the floor of his rig.

He started pounding on his computer terminal, demanding answers.

The idiot box had had hours to play with the data. It had a hypothesis ready.

"What the hell?" Frog did not like it. "Try again."

The machine refused. It knew it was right.

The computer said there was a thin place in the planetary mantle here. A finger of magma reached toward the surface. Convection currents from the deep interior had carried warmer radioactives into the pocket. Over the ages a fabulous lode had formed.

Frog fought it, but believed. He wanted to believe. He had to believe. This was what he had given his life to find. He was rich...

The practicalities began to occur to him when the euphoria wore off. Radioactivity would have to be overcome. Six kilometers of mantle would have to be penetrated. A way to beat the sun would have to be found because the lode was centered beyond the Shadowline's end... Mining it would require nuclear explosives, masses of equipment, legions of shadow generators, logistics on a military scale. Whole divisions of men would have to be assembled and trained. New technologies would have to be invented to draw the molten magma from the earth...

His dreams, like smoke, wafted away along the long, still corridors of eternity. He was Frog. He was one little man. Even Blake did not have the resources to handle this. It would take a decade of outrageous capitalization, with no return, just to develop the needed technologies.

"Damn!" he snarled. Then he laughed. "Well, you was rich for one minute there, Frog. And it felt goddamned good while it lasted." He had a thought. "File a claim anyway. Maybe someday somebody'll want to buy an exploitation franchise."

No, he thought. No way. Blake was the only plausible franchisee. He was not going to make those people any richer. He would keep the whole damned thing behind his chin.

But it was something to think about. It really was.

Piqued by the futility of it all, he ordered his computer to lock out any memories relating to the lode.

Eleven: 3031 AD

Cassius stepped into the study. Mouse remained behind him.

"You wanted me?"

Storm cased the clarinet, adjusted his eyepatch, nodded. "Yes. My sons are protecting me again, Cassius."

"Uhm?" Cassius was a curiosity in the family. Not only was he second in command, he was both Storm's father-in-law and son-in-law. Storm had married his daughter Frieda. Cassius's second wife was Storm's oldest daughter, by a woman long dead. The Storms and their captains were bound together by convolute, almost incestuous relationships.

"There's a yacht coming in," Storm said. "A cruiser is chasing her. Both ships show Richard's IFF. The boys have activated the mine fields against them."

Cassius's cold face turned colder still. He met Storm's gaze, frowned, rose on his toes, said, "Michael Dee. Again."

"And my boys are determined to keep him away from me."

Cassius kept his counsel as to the wisdom of their effort. He asked, "He's coming back? After kidnapping Pollyanna? He has more gall than I thought."

Storm chuckled. He killed it when Cassius frowned. "Right. It's no laughing matter."

Pollyanna Eight was the wife of his son Lucifer. They had not been married long. The match was a disaster. To understate, the girl was not Lucifer's type.

Lucifer was one of Storm's favorite children, despite his efforts to complicate his father's life. Lucifer's talents were musical and poetic. He did not have the good sense to pursue them. He wanted to be a soldier.

Storm did not want his children to follow in his footsteps. His profession was a dead end, an historical/social anomaly that would soon correct itself. He saw no future or glamour in his trade. But he could not deny the boys if they chose to remain with the Legion.

Several had become key members of his staff.

Of the men who had created the Legion only a handful survived. Grim old Cassius. The spooky brothers Wulf and Helmut Darksword. A few sergeants. His father, Boris, and his father's brothers and brothers of his own#8212;William, Howard. Verge, and so many more#8212;all had found their deaths-without-resurrection.

The family aged and grew weaker. And the enemy behind the night grew stronger... Storm grunted. Enough of this. He was becoming the plaything of his own obsession with fate.

"He's bringing her back, Cassius." Storm, smiled secretively.

Pollyanna was an adventuress. She had married Lucifer more to get close to men like Storm than out of any affection for the poet. Michael had had no trouble manipulating her unsatisfied lust for action.

"But, you see, when he added it all up he was more scared of me than he thought. I caught up with him on The Big Rock Candy Mountain three weeks ago. We had a long talk, just him and me. I think the knife did the trick. He's vain about his face. And he still worries about Fearchild."

Mouse did his best to remain small. His father's gaze had passed over him several times, a little frown clicking on and off each time. There would be an explosion eventually.

"You? Tortured? Dee?" Cassius could not express his incredulity as a sentence. "You're sure this isn't something he's cooked up to boost his ratings?"

Storm smiled. His smile was a cruel thing. Mouse did not like it. It reminded him that his father had a side that was almost inhuman.

"Centuries together, Cassius. And still you don't understand me. Of course Michael has an angle. That's his nature. And why do you think torture is out of character for me? I promised Michael I would protect him. All that means, and he knows it, is that I won't kill him myself. And I won't let him be killed with my knowledge."

"But... "

"When he crosses me I still have options. I showed him that on The Mountain."

Mouse shuddered as a narrow, wicked smile of understanding captured Cassius's lips. Cassius could not fathom the bond between the half-brothers. It pleased him that Storm had circumvented its limitations.

Cassius was amused whenever a Dee came to grief. He had his grievances. Fearchild was still paying for the hand.

He had been gone too long. He had forgotten their dark sides.

"To business," Cassius said. "If Michael has Pollyanna, and Richard is after him, there'll be shooting. We belong down in Combat."

"I was about to suggest that we go there." Storm rose. "Before my idiot sons rid me of this plague called Michael Dee." He laughed. He had paraphrased Lucifer, who had stolen the line from Henry II, speaking of Becket. "And poor pretty Pollyanna along with him."

Storm whistled. "Geri! Freki! Here!" The dogs ceased their restless pacing, crowded him expectantly. They were free to range the Fortress, but did so only in the company of their master.

Storm donned the long grey uniform cloak he affected, took a ravenshrike on one arm, strode off. Cassius trailed him by a half-step. Mouse hurried along behind them. The dogs ranged ahead, searching for the trouble they would never find.

"Mouse," Storm growled, stopping suddenly. "What the hell are you doing here?"

"I sent for him," Cassius replied in that cold metallic voice. Mouse shuddered. He was imagining it, of course, but Cassius sounded so deadly unemotional and lifeless... "I contacted my friends in Luna Command. They arranged it. The situation... "

"The situation is such that I don't want him here, Cassius. He has a chance to go his own direction. For God's sake, let him grab it. Too many of my children are caught in this trap already."

Cassius turned as Storm resumed walking. "Wait in my office. Mouse. I'll bring him around."

"Yes, sir."

Mouse began to feel what his father felt. An air of doom permeated the Fortress. A sense that great things were about to happen hung over them all. His father did not want him involved. Cassius thought he belonged. Mouse was shaken. A clash of wills between the two was inconceivable, yet his presence might precipitate one.

How could the Fortress be in danger? Combat simulation models suggested that only Confederation Navy had the strength to crack it. His father and Cassius got along well with the distant government.

Alone in the Colonel's inner office he began to brood. He realized he was mimicking his father. And he could not stop.

Was it Michael Dee?

The foreboding was almost palpable.

Twelve: 2844 AD

Costumed to the ears, wearing the heavy, silly square felt hat of a Family heir, Deeth stood beside his mother. Guests filed past the receiving line. The men touched his hands. The women bowed slightly. Pugh, the twelve-year-old heir of the Dharvon, honored him with a look that promised trouble later. In response Deeth intimidated the-ten-year-old sickly heir of the Sexon. The boy burst into tears. His parents became stiff with embarrassment.

The Sexon were the only First Family with a presence on Prefactlas. They had the most image to uphold.

Deeth recognized his error as his father gave him a look more promising than that of Dharvon w'Pugh.

He was not contrite. Hanged for a penny, hanged for a pound. The Sexon kid would have a miserable visit.

The evening followed a predictable course. The adults began drinking immediately. By suppertime they would be too far gone to appreciate the subtleties of his mother's kitchen.

The children were herded into an isolated wing of the greathouse where they could be kept out of the way and closely supervised. As always, the supervision broke down.

The children shed their chaperones and got busy establishing a pecking order. Deeth was the youngest. He could intimidate no one but the Sexon heir.

Sexon fortunes would decline when the boy assumed his patrimony.

The Dharvon boy had a special hatred for Deeth. Pugh was strong but not bright. Only by malign perseverance did he corner his prey.

Deeth refused to show it, but he was terrified. Pugh was not smart enough to know when to quit. He might do something that would force the adults to take official notice. Relations between the Dharvon and Norbon were strained enough. Further provocation could escalate into vendetta.

The call to supper, like a god out of a machine, saved the situation.

Why did his mother invite people with grudges against the Family? Why was a social slight less easily forgiven than a business beating?

He decided to become the richest Sangaree of all time. Wealth made its own rules. He would change things around so they became sensible.

Deeth found the meal unbearably formal and ritualistic.

It was a dismal affair. The alcohol had had its effect. Instead of raising spirits and stirring camaraderie, it had eased restraints on the envy, jealousy, and tempers of the Families the Norbon were excluding from the Osirian market.

Deeth struggled to keep smiling down that long table of sullen faces. The meal progressed lugubriously. The faces grew more antagonistic.

During the desserts the senior Dharvon,

The man was falling-down drunk, and had a reputation for verbal incontinence even when sober. He might say something that would push the Norbon into a corner of honor whence there was no exit save a duel.

The Dharvon was little brighter than his son. He did not have sense enough to avoid offending a better man. And the stupid pride of his heir would, of course, lead the Dharvon into vendetta. The Norbon Family would strike like a lion at a kitten and swallow the Dharvon whole.

But the mouth of a fool knows no restraint. The Dharvon kept pressing.

His neighbors edged away, dissociating themselves from his remarks. They shared his jealousies without sharing his stupidity. Sullenly neutral, they hovered like eager vultures.

Sangaree found feuds entertaining when they were not themselves involved.

Fate interceded just seconds before challenge became inescapable.

Rhafu burst into the hall. His face was red, frightened, and sweaty. He ignored the proprieties as he interrupted his employer.

"Sir," he said, puffing into the Norbon's face, "it's started. The field hands and breeders are attacking their overseers. Some of them are armed. With weapons from the wild ones. We're trying to get them under control in case there's an attack from the forest."

Guests buzzed excitedly. Heads and station masters shouted requests for permission to contact their own establishments. A general rising could not have been better timed. Prefactlas's decision-makers were far from their respective territories.

A few mumbled apologies for leaving ran from the table. What began as a babble of uncertainty escalated into a frightened clamor.

An officer of the Norbon Family forces compounded it. He galloped in, shouted over the uproar, "Sir! Everyone! A signal from

The silence died. Everybody tried to leave at once, to escape, to flee to his own station. The great terror of the Sangaree had befallen Prefactlas. The humans had located their tormentors.

A gleeful wild devil spun circles of terror around the hall. Children wept. Women screamed and wailed. Men cursed and shoved, trying to be first to escape.

There had been other station raids. The humans had been merciless. They never settled for less than total obliteration.

Prefactlas was an entire world, of course, and a world cannot be attacked and occupied like some pitiful little island in an ocean. Not without overpoweringly vast numbers of ships and men. And, though sparsely settled, Prefactlas had a well-developed defense net. Sangaree guarded their assets. Normally a flotilla could have done little but blockade the world.

But conditions were not normal. The decision-makers were concentrated far from the forces responsible for turning attacks. No one had yet found a way around Family pride and stubbornness and formed a centralized command structure. The various Family forces, because their masters were far away, would be loafing far from their battle stations. Or, if the slave rising were general, they would be preoccupied. Attacking quickly, the humans could be down before defenses could be manned and effective interception barrages launched.

Even Deeth saw it. And he saw what most of the adults did not. Attack and uprising were coordinated, and timed for the height of this party.

The humans were working with someone on Prefactlas.

Their commander need only take the Norbon station to seize control of the planet. Having eliminated the decision-makers and gotten their ships inside the defensive umbrella, they could deal with the other holdings piecemeal. They could conquer an entire world with an inferior force.

The whole thing smacked of raider daring. Nurtured by treachery, of course.

Some laughing human commander, smarter than most animals, was about to make himself a fortune.

Over the years since their discovery of the Sangaree, and the fact that they were considered animals, the humans had created scores of laws designed to encourage one another to respond savagely. Billions in bounties and prize moneys would go to the conquerors of a world. Even the meanest shipboard rating would be able to retire and live on his interest. A developed world was a prize with a value almost beyond calculation.

The fighting would be grim. Human hatred would be reinforced by greed.

Deeth's father was as quick as his son. Defeat and destruction, he saw, were inevitable. He told his wife, "Take the boy and dress him in slave garb. Rhafu, go with her. See that he's turned loose in the training area. They don't know each other. He'll pass."

Deeth's mother and the old breeding master understood. The Head was grasping at his only chance to save his line.

"Deeth," his father said, kneeling, "you understand what's happening, don't you?"

Deeth nodded. He did not trust himself to speak. Once he had examined and thought out the possibilities he had become afraid. He did not want to shame himself.

"You know what to do? Hide with the animals. It shouldn't be hard. You're a smart boy. They won't be expecting you. Stay out of trouble. When you get the chance, go back to Homeworld. Reclaim the Family and undertake a vendetta against those who betrayed us. For your mother and me. And all our people who will die here. Understand? You'll do that?"

Again Deeth dared only nod. His gaze flicked around the hall. Who were the guilty? Which few would see the sun rise?

"All right." His father enfolded him in a hug that hurt. He had never done that before. The Norbon was not a demonstrative man. "Before you go."

The Norbon took a small knife from his pocket. He opened a blade and scraped the skin on Deeth's left wrist till a mist of blood droplets oozed up. Then he used a pen to ink a long series of numbers. "That's where you'll find your Wholar, Deeth. That's Osiris. The only place those numbers exist is in my head and on your wrist. Take care. You'll need that wealth to make your return."

Deeth forced a weak smile. His father was brilliant, disguising the most valuable secret of the day as a field hand's serial.

The Norbon hugged him again. "You'd better go. And hurry. They'll come down fast once they're into their run."

A raggedy string of roars sounded out front. Deeth smiled. Someone had activated the station defenses. Missiles were launching.

Answering explosions killed his pleasure. He hurried after his mother and Rhafu. White glare poured through the windows. The atmosphere above the station protested its torment. Guests kept shrieking.

The preparatory barrages had begun. The station's defenders were trying to fend them off.

The slave pens were utter chaos. Deeth heard the fighting and screaming long before he and Rhafu arrived on the observation balcony.

Household troops were helping the slave handlers, and still the animals were not under control. Corpses littered the breeding dome. Most were field hands, but a sickening number wore Norbon blue. The troops and handlers were handicapped. They had to avoid damaging valuable property.

"I don't see any wild ones, Rhafu."

"That is curious. Why provide weapons without support?"

"Tell them not to worry about saving the stock. They won't matter if the human ships break through."

"Of course." After an introspective moment, Rhafu said, "It's time you went." He gave Deeth a hug as powerful as his father's had been. "Be careful, Deeth. Always think before you do anything. Always take the long view. Don't ever forget that you're the Family now." He ran the back of a wrist across his eyes. "Now, then. I've enjoyed having you here, young master. Don't forget old Rhafu. Kill one for me when you get back to Homeworld."

Deeth saw death in Rhafu's watery eyes. The old adventurer did not expect to survive the night. "I will, Rhafu. I promise."

Deeth gripped one leathery old hand. Rhafu was still a fighter. He would not run. He would die rather than let animals shatter his courage and the confidence of his own superiority.

Deeth started to ask why he had to run away when everyone else was going to stand. Rhafu forestalled him.

"Listen closely, Deeth. Go down the stairs at the end of the balcony. All the way down. There'll be two doors at the bottom. Use the one on your right. It opens into the corridor that passes the training area. There shouldn't be anyone in it. Go to the end of the hall. You'll find two more doors. Use the one marked Exit. It'll put you outside in one of the vegetable fields. Go to the sithlac dome and follow its long side. Keep going in a straight line out from its end. You should reach the forest in an hour. Keep on going and you'll run into an animal village. Stay with them till you find a way off planet. And for Sant's sake make sure you pretend you're one of them and they're equals. If you don't, you're dead. Never trust one of them, and never get close to any of them. Understand?"

Deeth nodded. He knew what had to be done. But he did not want to go.

"Go on. Scoot," Rhafu said, swatting him on the behind and pushing him toward the stair. "And be careful."

Deeth walked to the stairwell slowly. He glanced back several times. Rhafu waved a last farewell, then turned away, hiding tears.

"He'll die well," Deeth whispered.

He reached the emergency exit. Cautiously, he peeped outside. The fields were not as dark as he had expected. Someone had left the lights on in the sithlac dome. And the slave barracks were burning. Had the animals fired them? Or had the bombardment done it?

Little short-lived suns kept flaring between the stars overhead. A long, rolling thunder of chemical explosions came from the far side of the station. The launch pits had been hit. The shriek of rising missiles was replaced by secondary explosions.

The humans were getting close. Deeth looked up into the heart of the constellation Rhafu had dubbed the Krath, after a rapacious bird of Homeworld. The human birthstar lay there somewhere.

He could not distinguish the constellation. There were scores of new stars up there, all of them too bright, and visibly brightening.

The humans were on the downward leg of their penetration run. He would have to hurry to clear the perimeter they would establish with their assault craft.

He sprinted for the side of the sithlac dome.

By the time he reached the dome's far end the new stars had swollen into small, bright suns. Missile exhausts rayed from them in angry swarms. He could hear the craft rumbling over the explosions stalking through the station.

They were just a few thousand feet up now, and braking in. His escape would be close. If he made it at all.

A flight of missiles darted toward the bright target of the dome. Deeth ran again, sprinting straight out into the darkness. Explosions tattooed behind him. Blasts hurled him forward, tumbled him over and over. The dome lights died. He rose, stumbled ahead, fell, rose, and went on. His nose was bleeding. He could not hear.

He could not see where he was going. The flashing of explosions kept his eyes from adapting as quickly as they should.

The assault craft touched down.

The nearest landed so close Deeth was singed by the hot wash spreading beneath it. He kept shambling toward the forest, ignoring the treacherous ground. When he was safe he paused to watch the humans tumble off their boat and link up with the craft that had landed to either side. The burning station splashed them with eerie light.

Deeth recognized them. They were Force Recon, the cream of the Confederation Marines, the humans' best and meanest. Nothing would escape their circle.

He cried for his parents, and Rhafu, then wiped the tears away with the backs of his fists. He trudged toward the forest, indifferent to the fact that the humans might spot him on anti-personnel radar. Each hundred steps he paused to look back.

Dawn was near when he passed the first trees. They rose like a sudden palisade, crowding a straight line decreed by the station's planners. He felt as though he had stepped behind a bulwark against doom.

Once his ears had recovered he had heard stealthy movements around him. He was not alone in his flight. He avoided contact. He was too shaken, and had too poor a command of the slave tongue, to handle questions from animals. The wild ones used a different language. He expected to have less trouble passing with them. If he could find them.

One found him.

He was a quarter-mile into the forest when a raggedy, smelly old man with a crippled leg pounced on him. The attack was so sudden and unexpected that Deeth had no chance. His struggles earned him nothing but a fist in the face. The blow calmed him. He bit down on a tongue that had been damning the old man in High Sangaree.

"What are you doing, please?" he ventured in the animal language.

The old man hit him again. Before he could do more than groan, a sack had been flung over his head, skinned down to his ankles, and tied shut. A moment later, head downward and miserable, he was hoisted onto a bony shoulder.

He had become booty.

Thirteen: 3052 AD

My father had an unusual philosophy. It was oblique, pessimistic, fatalistic. Judge its tenor by the fact that he read Ecclesiastes every day.

He believed all existence was a rigged game. Good strove with Evil in vain. Good could achieve occasional localized tactical victories, but only because Evil was toying with it, certain of final victory. Evil knew no limits. In the end, when the scores were tallied, Evil would be the big winner. All a man could do was face it with courage, fight though defeat was inevitable, and delay the hour of defeat as long as possible.

He did not see Good and Evil in standard terms. The Good and Evil most of us see he simply considered matters of viewpoint. The "I" is always on the side of the angels. The "They" are always wicked. He thought an absolute Islamic-Judeo-Christian Evil a weak, irrational joke.

Entropy is an approximate cognate for what Gneaus Julius Storm called Evil. An anthropomorphic, diabolic sort of entropy with a malign lust for devouring love and creativity, which, I think, he considered to be the main constituents of Good.

It was an unusual outlook, but you have to accept that it was valid for him before you can follow him through the maze called the Shadowline.

#8212;Masato Igarashi Storm

Fourteen: 3031 AD

Storm, Cassius, and the dogs crowded into an elevator. It dropped away toward the Traffic Control and Combat Information Center at the planetoid's heart.

Benjamin, Homer, and Lucifer whirled when their father entered the Center. Storm surveyed their faces grimly. The glow of the spatial display globes, overplayed by the changing light keys of the tactical computer's situation boards, splashed them with ever-changing color. No one spoke.

Storm's sons stared at their feet like shamed boys caught playing with matches. Storm half turned to Cassius, eye on the senior watchstander. Cassius inclined his head. The officer would have to explain his failure to report ships in detection. He would be reminded of his debt to Gneaus Storm. It would be a tempestuous admonition.

The officer's failure was beyond Cassius's comprehension. He never let his hatred of the Dees impair his trust. The Dees were a raggedy-assed gaggle of hypocritical thieves, boosters, and news managers. They were a waste of life-energy. But... Cassius suppressed his feelings because he had faith in Storm's judgment. This watch officer had not been with the Legion long enough to have developed that faith.