"1633" - читать интересную книгу автора (Weber David, Flint Eric)

PS3573.E217 A615 2002

813'.5-dc21 2002023215 Distributed by Simon Schuster 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Production by Windhaven Press, Auburn, NH Printed in the United States of America

To Sharon and Lucille,

for putting up with us while

we disappeared into this book

Other Books in This Series:

BAEN BOOKS by DAVID WEBER

Honor Harrington:

edited by David Weber:

with Steve White:

Baen Books by Eric Flint

Joe's World series:

The Belisarius series, with David Drake:

Part I

|

|

|

Chapter 1

"How utterly delightful!" exclaimed Richelieu. "I've never seen a cat with such delicate features. The coloration is marvelous, as well."

For a moment, the aristocratic and intellectual face of France's effective ruler dissolved into something much more youthful. Richelieu ignored Rebecca Stearns entirely, for a few seconds, as his forefinger played with the little paws of the kitten in his lap. Rebecca had just presented it to Richelieu as a diplomatic gift.

He raised his head, smiling. "A 'Siamese,' you call it? Surely you have not managed to establish trade relations with southeast Asia in such a short time? Even given your mechanical genius, that would seem almost another miracle."

Rebecca pondered that smile, for a moment, while she marshaled her answer. One thing, if nothing else, had become quite clear to her in the few short minutes since she had been ushered in to a private audience with the cardinal. Whatever else he was, Richelieu was possibly the most intelligent man she had ever met in her life. Or, at least, the shrewdest.

And quite charming, in person-that she had not expected. The combination of that keen intellect and the personal warmth and grace was disarming to someone like Rebecca, with her own basically intellectual temperament.

She reminded herself, very firmly, that being disarmed in the presence of Richelieu was the one thing she could least afford. For all his brains and his charm, the cardinal was almost certainly the most dangerous enemy her nation faced at the moment. And while she did not think Richelieu was cruel by nature, he had demonstrated before that he was quite prepared to be utterly ruthless when advancing what he considered the interests of his own nation.

She decided to pursue the double meaning implicit in the cardinal's last sentence.

" 'Another' miracle?" she asked, raising an eyebrow. "An interesting term, Your Eminence. As I recall, the most recent characterization you gave the Ring of Fire was 'witchcraft.' "

Richelieu's gentle smile remained as steady as it had been since she entered his private audience chamber. "A misunderstanding," he insisted, wiggling his fingers dismissively. Then, paused for a moment to admire the kitten batting at the long digits. "My error, and I take full responsibility for it. Always a mistake, you know, to jump to conclusions based on scant evidence. And I fear I was perhaps too influenced at the time by the views of Father Joseph. You met him yesterday, I believe, during your audience with the king?"

Another double meaning was buried in that sentence as well. Subtly, Richelieu was reminding Rebecca that her alternative to dealing with

Rebecca controlled the natural impulse of an intellectual to

"Let the other side do most of the talking," he'd told her. "On average, I'd say anyone's twice as likely to screw up with their mouth open than closed."

The cardinal, of course, was quite familiar with the ploy himself. Silence lengthened in the room.

For an intellectual, silence is the ultimate sin. So, again, Rebecca found herself forced to

She took refuge in memories of her husband. Mike, standing in the doorway to their house in Grantville, his face somewhat drawn and unhappy, as he bid her farewell on her diplomatic journey to France and Holland. The same face-she found this memory far more comforting-the night before, in their bed.

Something in the smile which came to her face at

"The 'Ring of Fire,' as you call it-which brought your 'Americans' and their bizarre technology into our world-was enough to confuse anyone, madame. But further reflection, especially with further evidence to base it upon, has led me to the conclusion that I was quite in error to label your… ah, if you will forgive the term, bizarre new country the product of 'witchcraft.' "

Richelieu paused for a moment, running his fingers down his rich robes. "Quite inexcusable on my part, really. Once I had time to ponder the matter, I realized that I had veered perilously close to Manicheanism." With a little chuckle: "And how long has it been since

Rebecca decided it was safe enough to respond to the witticism with a little chuckle of her own. Nothing more than that, though. She could practically

And that thought, too, reinforced her own serene smile. In truth, Mike Stearns was very far removed from a "patriarch." He would be amused, Rebecca knew, when she told him of her self-admonition. ("I will be good God-damned. You mean that

It was another little defeat for Richelieu. Something in the set of his smile-a trace of stiffness-told her so. Again, the cardinal ran fingers down his robe, and resumed speaking.

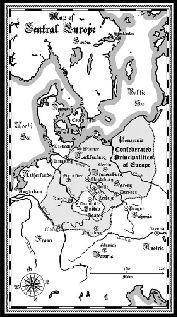

"No, only God could have caused such an incredible transposition of Time and Space. And your term 'the Ring of Fire' seems appropriate." Very serene, now, his smile. "As I'm sure you are aware, I have long had my agents investigating your 'United States' in Thuringia. Several of them have interviewed local inhabitants who witnessed the event. And, indeed, they too-simple peasants-saw the heavens open up and a halo of heatless flame create a new little world in a small part of central Germany.

"Still-" he said, abruptly, holding up a hand as if to forestall Rebecca's next words. (Which, in fact, she'd had no intention of speaking.) "Still, the fact that the

And here it comes, thought Rebecca. The new and official party line.

She was privileged, she realized. Her conversations with the courtiers at the royal audience the night before had made clear to her that France's elite was still groping for a coherent ideological explanation for the appearance of Grantville in the German province of Thuringia. Having now survived for two years-not to mention defeating several attacking armies in the process, at least one of them funded and instigated by France-the Americans and the new society they were forging could no longer be dismissed as hearsay. And the term "witchcraft" was… petty, ultimately.

Richelieu, she was certain, had constructed such an ideological explanation-and she would be the first one to hear it.

"Have you considered the history of the world which created your Americans?" asked Richelieu. "As I'm sure you also know, I've obtained"-here came another dismissive wiggle of the finger-"through various means, several of the historical accounts which your Americans brought with them. And I've studied them all, very thoroughly."

In retrospect, of course, the thing was obvious. Any ruler or political figure in the world, in the summer of the year 1633, would eagerly want to see what lay in store for them in the immediate years to come. And the consequences of that knowledge would be truly incalculable. If a king knows what will happen a year or two from now, after all, he will take measures to make sure that it either happens more quickly-if he likes the development-or doesn't happen at all, if otherwise.

And in so doing, of course, will rapidly scramble the sequence of historical events which led to that original history in the first place. It was the old quandary of time travel, which Rebecca herself had studied in the science fiction novels which the town of Grantville had brought with it also. And, like her husband, she had come to the conclusion that the Ring of Fire had created a new and parallel universe to the one from which Grantville-and the history which produced it-had originally come.

As she ruminated, Richelieu had been studying her. The intelligent dark brown eyes brought their own glum feeling. And do not think for a moment that the cardinal is too foolish not to understand that. He, too, understands that the history which was will now never be-but also understands that he can still discern broad patterns in those events. And guide France accordingly.

His next words confirmed it. "Of course, the

The wiggling fingers, this time, were not so much dismissive as demonstrative. "All the rest follows. The massacre of six million of your own fellow Jews, to name just one instance. The atrocities committed by such obvious monsters as Stalin and those Asian fellows. Mao and Pol Pot, if I recall the names correctly. And-let us not forget-the destruction of entire cities and regions by regimes which, though perhaps not as despotic, were no less prepared to wreak havoc upon the world. I will remind you, madame, that the United States of America which you seem determined to emulate in this universe did not shrink for an instant from incinerating the cities of Japan-or cities in Germany, for that matter, who are now your neighbors. Half a million people-more likely a million, all told-exterminated like so many insects."

Rebecca practically clamped her jaws shut. Her instincts were to shriek argument in response. Yes? And the current devastation which you have unleashed on Germany? The Thirty Years War will kill more Germans than either world war of the 20th century! Not to mention the millions of children who die in your precious aristocratic world every year from hunger, disease and deprivation-even during peacetime-all of which can be quickly remedied!

But she remained true to her husband's advice. There was no point in arguing with Richelieu. He was not advancing a hypothesis to be tested, here. He was simply letting the envoy from the United States know that the conflict was not over, and would not be over, until one or the other side triumphed. For all the charm, and civility, and the serenity of the smile, Richelieu was issuing a declaration of war.

And, indeed, his next words: "So it all now seems clear to me. Yes, God created the Ring of Fire. Absurd to label such a miraculous event a thing of petty 'witchcraft.' But he did so in order to warn us of the perils of the future, that we might be armed to avoid them. That we might be steeled in our resolve to create a world based on the sure principles of monarchy, aristocracy, and an established church. Perils of which, my dear Madame Stearns, you and your people-meaning no personal disrespect, and implying no

The cardinal rose gracefully to his feet and gave Rebecca a polite bow. "And now, I'm afraid, I must attend to the king's business. I hope you enjoy your stay in Paris, and if I may be of any assistance please call upon me. How soon do you plan to depart for Holland? And by what means?"

Richelieu's charm was back in full force, as he escorted her to the door. "I strongly urge you to take the land route. The Channel-even the North Sea-is plagued with piracy. I can provide you with an escort to the border of the Spanish Netherlands, and I'm quite sure I can arrange a safe passage through to Holland. Yes, yes, France and Spain are antagonists at the moment. But despite what you may have heard, my personal relations with Archduchess Isabella are quite good. I am certain the Spaniards will not place any obstacles in the way."

The statement was ridiculous, of course. The very

"Perhaps," was all she said. Smiling serenely, as she passed through the door.

Chapter 2

After the door closed, Richelieu turned away and resumed his seat. A moment later, Etienne Servien came through a narrow door at the rear of the room. To all appearances, the door to a closet; in reality, the door which connected to the chamber from which Servien could spy upon the cardinal's audiences whenever Richelieu so desired. Servien was one of the cardinal's handpicked special agents called

"You heard?" grunted Richelieu. Servien nodded.

Richelieu threw up his hands, as much with humor as exasperation.

"What a

"I never would have thought it possible, Etienne. A Sephardic Jewess-Doctor Balthazar Abrabanel's daughter, no less! That breed can talk for hours on end, ignoring hunger all the while. Philosophers and theologians, the lot. I'd expected to simply smile and let her fill my ears with information. Instead-"

He chuckled ruefully. "Not often

Servien shrugged. "The Sephardic Jews also provide Europe and the Ottoman Empire with most of its bankers, Your Eminence-not a profession known for being loose-lipped. Moreover, while he may be a doctor and a philosopher, Balthazar Abrabanel, as well as his brother Uriel, are both experienced spies.

" 'Grand strategy,' " echoed Richelieu. "

"Either of them, or both. I assure you, not even Satan himself could have deduced our plans from anything you spoke. The woman is intelligent, yes. But, as you said, not a witch."

The cardinal pondered silently for a moment, his lean face growing leaner still.

"Still, she is too intelligent," he pronounced at length. "I hope she will accept my offer to provide her with an escort for a journey overland to the Spanish Low Countries. That would enable us-in a dozen different ways-to delay her travel long enough for our purposes. But…"

He shook his head. "I doubt it. She will almost certainly deduce as much, and choose to make her own arrangements for traveling by sea to Holland. And we simply

Servien pursed his lips. "I could certainly keep her away from Le Havre, Your Eminence. Not

Richelieu interrupted him with a gesture which was almost angry. "Desist, Etienne! I realize that you are trying to spare me the necessity of making this decision. Which, the Lord knows, I find distasteful in the extreme. But reasons of state have never been forgiving of the kindlier sentiments." He sighed heavily. "Necessity remains what it is. Do keep her from Le Havre, of course. One of the smaller ports would be far better anyway, for… what is needed."

The cardinal looked down at the kitten, still playing with his long forefinger. "And, who knows? Perhaps fortune will smile on us-and her-and she will make a bad decision."

The gentle smile returned. "There are few enough of God's marvelous creatures in this world. Let us hope we will not have to destroy yet another one. On your way out, Etienne, be so kind as to summon my servant."

The dismissal was polite, but firm. Servien nodded and left the room.

A moment later, Desbournais entered the room. Desbournais was the cardinal's

The cardinal lifted the kitten and held it out to Desbournais. "Isn't he gorgeous? See to providing for him, Desbournais-and well, mind you."

After Desbournais left, Richelieu rose from the chair and went to the window in his chamber. The residence the cardinal used whenever he was in Paris-a palace in all but name-was a former hotel which he had purchased on the Rue St. Honorй near the Louvre. He'd also purchased the adjoining hotel in order, after having it razed, to provide him with a better view of the city.

As he stared out the window, all the kindliness and gentleness left his face. The cold, stern-even haughty-visage which stared down at the great city of Paris was the one that his enemies knew. For all his charm and grace, Richelieu could also be intimidating in the extreme. He was a tall man, whose slenderness was offset by the heavy and rich robes of office he always wore. His long face, with its high forehead, arched brows, and large brown eyes, was that of an intellectual, yes. But there was also the slightly curved nose and the strong chin, set off by the pointed and neatly barbered beard-those, the features of a very different sort of man.

Hernan Cortez would have understood that face. So would the duke of Alba. Any of the world's conquerors would have understood a face which had been shaped, for years, by iron resolve.

"So be it," murmured the cardinal. "God, in his mercy, creates enough marvelous creatures that we can afford to destroy those we must. Necessity remains."

"Well, how'd it go?" asked Jeff Higgins cheerfully. Then, seeing the tight look on Rebecca's face, his smile thinned. "That bad? I thought the guy had a reputation for being-"

Rebecca shook her head. "He was gracious and polite. Which didn't stop him-not for a second-from issuing what amounted to a declaration of total war."

Sighing, she removed the scarf she had been wearing to fend off a typical Paris drizzle. Seeing it was merely a bit damp, she spread it out to dry over the back of one of the chairs in the sitting room of the house which the delegation from the United States had rented in Paris. Then, seeing Heinrich Schmidt entering the room from the kitchen, Rebecca smiled ruefully.

"I'm afraid-very much afraid-that you gentlemen may soon be earning your pay."

Heinrich shrugged. So did Jeff, who, although he had a special assignment on this mission, was-along with his friend Jimmy-also a soldier in the U.S. Army.

The next person to enter the room was Jeff's wife. "So what's happening?" she demanded, her German accent still there beneath the fluent and colloquial English.

Rebecca's smile widened. She always found the contrast between Jeff and Gretchen somewhat amusing, in an affectionate sort of way. What the Americans called an "odd couple," based on one of those electronic dramas which Rebecca still found fascinating, for all the hours she'd spent watching television-even hosting a TV show of her own.

Jeff Higgins, though he had been toughened considerably in the two years since his small American town had been deposited into the middle of war-torn central Europe in the year 1631, still exuded a certain air of what the Americans called a "geek" or a "nerd." He was tall, yes; but also overweight-still, for all the exercise he now got. Although Jeff had recently celebrated his twentieth birthday, his pudgy face looked like that of a teenager. A pug nose between an intellectual's eyes, peering near-sightedly through thick glasses. About as unromantic a figure as one could imagine.

His wife, on the other hand…

Gretchen, nee Richter, was two years older than Jeff. She was not precisely "beautiful," not with that strong nose and that firm jaw, even leaving aside her tall stature and shoulders broader than those of most women. But, still, so good-looking that men's eyes invariably followed her wherever she went. The fact that Gretchen was, as the Americans put it, "well built," only added to the effect-as did the long blond hair which cascaded over those square shoulders.

Gretchen, unlike Jeff, was native-born. Like Rebecca herself, she was one of the many 17 th -century Europeans who had been swept up by the Ring of Fire and cast their lot with the newly arrived Americans. Including, as was true of Rebecca herself, marriage to an American husband.

Regardless of her native origins, Gretchen had adopted the attitudes and ideology of the Americans with the fervor and zeal of a new convert. If almost all the Americans were devoted to their concepts of democracy and social equality, Gretchen's devotion-not surprisingly, given the horrors of her own life-tended to frighten even them.

Rebecca was reminded of that again, as Gretchen idly played with the edge of her vest. The blond woman's impressive bosom disguised the thing perfectly, but Rebecca knew full well that Gretchen was carrying her beloved 9mm automatic in a shoulder holster. She had sometimes been tempted to ask Jeff if his wife

For the most part, however, Rebecca's smile was simply due to the fact that she both liked and-very deeply-

Gretchen might frighten others, but she never frightened Mike Stearns. He did not always agree with her, true enough-and, even when he did, often found her tactics deplorably crude. But, no matter how high he had risen in this new world, Rebecca's husband was still the same man he had always been-the leader of a trade union of Appalachian coal miners, a folk which had its own long and bitter memories of the abuses of the powerful and mighty.

"Don't kid yourself," Mike had once growled to Rebecca, on the one occasion where she had expressed some exasperation with Gretchen's zeal and disregard for the complexities of the political situation. They had just finished breakfast, and Mike was helping Rebecca with the dishes. For all that she had grown accustomed to it, Rebecca still thought there was something charming about having such a very masculine sort of husband working alongside her in kitchen chores.

"When push comes to shove, the only people I can

Staring out the kitchen window of their house in Grantville, he shook his head firmly. "As regretful as he might find the necessity, Gustav II Adolf will cut our throats in a heartbeat, under the right circumstances. Whereas without us, Gretchen and her radical democratic Committees of Correspondence are so much dog food-and she knows it perfectly well, don't think she doesn't. However often I may piss her off by my 'compromises with principle,' she knows she needs me as much as I need her."

When he turned away from the window, his blue eyes had been dancing with humor. "Besides, she's

Rebecca nodded. She'd devoured books on American history-

Mike smiled. "Well, there's a little anecdote that illustrates my point. Malcolm X once made the wisecrack that the reason the white establishment was willing to talk to the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., was because they

A motion outside the window must have caught his eye, because Mike turned away from her for a moment. Whatever he saw caused his smile to broaden into a grin.

"Speak of the devil… Come here, love-I'll show you another example of what I'm talking about."

When Rebecca had come to the window, she'd seen the figure of Harry Lefferts sauntering past on the street below. It was early in the morning, and from the somewhat self-satisfied look on his face, Rebecca suspected that Harry had spent the night with one of the girlfriends he seemed to attract like a magnet. Harry was a handsome young man, with the kind of daredevil self-confidence and easy humor which attracted a large number of young women.

She was a little puzzled. Harry's amatory prowess hardly seemed relevant to the discussion she was having with Mike. But then, seeing the little swagger in Harry's stride-nothing extravagant, just the subtle cockiness of a young man who was

Whatever women might find attractive about Harry Lefferts, not all men did. Many, yes-those who hadn't chosen to cross him. Those who did cross him tended to discover very rapidly what the Americans meant by their expression "hard-ass." Harry was a muscular man, and his mind was every bit as "hard-ass" as his body. When he wanted to be, Harry Lefferts could be rather frightening.

"Did I ever tell you how I'd always use Harry in negotiations?" Mike murmured in her ear. "Back in my trade-union days?"

Rebecca shook her head-then, laughed, as Mike's murmur turned into a more intimate gesture involving a tongue and an ear.

"Stop it!" She pushed him away playfully. "Didn't you get enough last night?"

Mike grinned and sidled toward her. "Well, I'd always make sure that Harry was on the negotiating team when we met with the company representatives. His job was to sit in the corner and, whenever I'd start making noises about maybe agreeing to a compromise, start glaring at me and growling. Worked like a charm, nine times out of ten."

Rebecca laughed again, avoiding the sidle. Oddly, perhaps, by moving into a corner of the kitchen.

"I pretty much think of Gretchen the same way," Mike murmured. Sidling, sidling. The murmur was becoming a bit husky. "The nobility of Europe hates my guts. But then they see Gretchen sitting in the corner… growling, growling…"

She was boxed in, now, trapped. Mike, never a stranger to tactics, swooped immediately.

"No," he said. "As it happens, I

The memory of what had followed warmed Rebecca, at the same time as it brought its own frustrations. She envied Jeff and Gretchen for having been able to take this long journey together-never more so than when she heard the noises they made in an adjoining bedroom, and Rebecca found herself pining for her own bed back in Grantville. With Mike, and his warm and lovely body, in it.

But… there had been no way for Mike to come. He was the President of the United States, and his duties did not allow him to be absent for more than a few days.

Something in her face must have registered, for she saw Gretchen smiling in a way which was both self-satisfied and a little serene. However much they might seem like an "odd couple" to others, Rebecca knew, Gretchen and Jeff were every bit as devoted to each other as were she and Mike. And, judging from the noises they made in the night-

But perhaps she was reading the wrong thing into that smile. If nothing else, Gretchen's fervent ideological beliefs often made her a bit self-satisfied and serene.

"What did you expect?" demanded the young German woman. "A cardinal! And the same stinking pig who tried to have our children massacred at the school last year, don't forget that either."

Rebecca hadn't forgotten. That memory, in fact, had been as much of a help as her husband's advice, during her interview with Richelieu. Charming and gracious the man might be. But Rebecca did not allow herself to forget that he was also perfectly capable of being as deadly as a viper-and just as cold-bloodedly merciless.

Still…

There would always be a certain difference in the way Rebecca Stearns, nee Abrabanel, would look at the world compared to Gretchen. For Rebecca, for the most part, the atrocities committed by Europe's rulers had always remained at arm's length. Not so, for Gretchen. Her father murdered before her eyes; she herself gang-raped by mercenaries and then dragooned into becoming their camp follower; her mother taken away years before by other mercenaries, to an unknown fate; half her family dead or otherwise destroyed-and all of it, all that horror, simply because Europe's nobility and princes had chosen to quarrel over their competing privileges. The fact that they would shatter Germany and slaughter a fourth of its population in the process did not bother them in the least.

Rebecca was an opponent of that aristocratic regime, true enough, and, along with her husband, had set herself the task of replacing it with a better one. But she simply never felt the sheer

"Which," Rebecca muttered to herself, "is not perhaps such a bad idea, everything considered."

"What was that?" asked Heinrich.

The major's face exhibited its own serenity. For all his youth-Heinrich was only twenty-four-the former mercenary had already seen more of bloodshed and war's ruin than most soldiers, in most of history's eras, ever saw in a lifetime. Rebecca liked Heinrich, to be sure. But the man's indifference to suffering sometimes appalled her. Not the indifference itself, so much as the cause of it. Heinrich Schmidt was a rather warm-hearted man, by temperament. But the years he had spent in Tilly's army after being forcibly "recruited" at the age of fifteen had left him with a shell of iron. He had enrolled readily enough in the American army, when given the chance. And Rebecca was quite sure that, in his own way, Heinrich was as devoted to his new nation as she was. Still, when all was said and done, the man retained a mercenary's callous attitudes in most respects.

"Never mind," responded Rebecca. "I was just reminding myself"-here, a little nod to Gretchen-"that Richelieu is capable of anything."

She pulled out the chair over which she'd spread the scarf and sat down. "Which brings us directly to the subject at hand. There's no point in remaining in Paris any longer. So the question posed is: by what route do we try to reach Holland?"

A motion in the doorway drew her eyes. Jeff's young friend Jimmy Andersen had entered from the kitchen. Behind him, Rebecca could see the other five soldiers in Heinrich's detachment.

She waited until all of them had come into the room and were either perched somewhere or leaning against the walls. Rebecca suspected that her very nondictatorial habits would have astonished most ambassadors of history. She dealt with her entourage as colleagues, not as subordinates. But she didn't care. She was an intellectual herself, by temperament, and enjoyed the process of debate and discussion.

"Here's the choice," she explained, once all of them were listening. "We can take the land route or try to hire a coastal lugger. If the first, Richelieu has offered to provide us an escort to Spanish territory and assures me he can obtain the agreement of the Spanish to pass us along to the United Provinces."

Gretchen and Jeff were already shaking their heads. "It's a trap," snarled Gretchen. "He'll set up an ambush along the way."

Heinrich was also shaking his head, but the gesture was aimed immediately at Gretchen.

"Not a chance of that," he said firmly. "Richelieu's a

Gretchen was glaring at him, but Heinrich was unfazed. "Yes, he

"I agree with Heinrich," interjected Rebecca. "Not the least of the reasons for Richelieu's success is that people trust him. His word is his bond, and all that. It's

She reached back and pulled the scarf off the seat's backrest. It was dry enough, so she began folding it. "I have no doubt at all that our

Heinrich was chuckling softly. "We'd be 'enjoying' the longest damn trip anyone ever took to Holland from Paris. Not more than a few hundred miles-and I'll wager anything you want to bet it would take us

Now that Gretchen's animosity had been given a new target, the woman's usual quick intelligence returned. "Yeah, easy enough. Broken axles every five miles. Lamed horses. Unexpected detours due to unexpected floods. Every other bridge washed out-and, how strange, nobody seems to know where the fords are. At least two weeks at the border, squabbling with Spanish officials. You name it, we'll get it."

Jeff, throughout, had been studying Rebecca. "So what's the problem with the alternative?"

Rebecca grimaced. "There's something happening in the ports of northern France that Richelieu doesn't want us to see. I don't know what it might be, but it's more than simply this alliance with the Dutch. I'm almost sure of it. That means"-she smiled at Heinrich-"and

"You're right," agreed Heinrich. "We'll have to take ship in one of the smaller and more distant ports."

The major, clearly enough, was thinking ahead. The man had a good and experienced soldier's instinctive grasp for terrain, to begin with. And, where Rebecca had spent the past two years devouring the books which Grantville had brought with it, Heinrich had been just as passionately devoted to the marvelous maps and atlases which the Americans possessed. By now, his knowledge of Europe's geography was well-nigh encyclopedic.

"I still don't see the problem," said Jeff. "So what if we add another two or three days to the trip? We'd still be able to make it to Holland within two weeks."

"Pirates," replied Heinrich and Rebecca, almost simultaneously. Rebecca smiled; then, nodding toward Heinrich, urged him to explain.

"The English Channel is infested with the bastards," growled the major. "Has been for centuries-and maybe never as badly as now, what with the French and Spanish preoccupied with their affairs on the Continent and that sorry-ass Charles on the throne in England."

Five of the six soldiers in the kitchen nodded. The sixth, Jimmy Andersen-who, except for Jeff, was the only native-born American in the group-was practically goggling.

"Pirates? In the English Channel?"

Rebecca found it hard not to laugh aloud. For all that they had been somewhat acclimatized in the two years since their arrival in 17 th -century Europe, she had often found that Americans still tended to unconsciously lapse into old ways of thinking. For Americans, she knew, anything associated with "England" carried with it the connotations of "safe, secure, even stodgy." The idea of

"Where do they come from?" demanded Jimmy.

"North Africa is where a lot of them are based," replied Heinrich. With a shrug: "Of course, they're not all Moors, by any means. The Spanish license 'privateers' operating out of Dunkirk and Ostend against Dutch shipping, and the Dunkirkers are none too picky about their targets. And even for the Moors, probably half the crews, at least, are from somewhere in Europe. The world's scavengers."

Jimmy was still shaking his head with bemusement. But Jeff, always quicker than his friend to adjust to reality, was giving Rebecca a knowing look.

"So what you're suggesting, in short, is that if we take the sea route… how hard would it be for Richelieu to

Rebecca wasn't sure herself. Neither, judging from his expression, was Heinrich.

Gretchen, of course, was.

"Of course he will!" she snapped. "The man's a spider. He has his web everywhere."

With Gretchen, as always, response was as certain as analysis. Sure enough, just as Rebecca had thought, the 9mm was in its place. A moment later, Gretchen had it in hand and was laying it firmly down on the table in front of her.

"Pirates it is," she pronounced, sweeping the room with a hard gaze. "Let's give them a taste of

A harsh-and approving-laugh came from the soldiers. Rebecca looked at Heinrich.

He shrugged. "Seems as good a plan as any."

Rebecca now looked to Jeff and Jimmy. Jeff, not to her surprise, had a stubborn expression which showed clearly that he was standing with his wife. Jimmy…

This time she

"Oh, how cool! We can try out the grenade launchers!"

Chapter 3

Dr. James Nichols finished washing off his hands and turned away from the sink, fluttering his hands in the air in order to dry them. Even in the hospital, Mike knew, towels were in such short supply that James had decreed that medical personnel should use them as little as possible.

He braced himself for the inevitable complaint. But, other than scowling slightly, the doctor simply shook his head and walked over to the door.

"Let's get out of here and let the poor woman get some sleep."

Mike opened the door for the doctor, whose hands were still damp, and followed him out into the corridor. Wondering, a bit, how the sick woman was going to get much sleep with her entire family crowded around the bed.

A bit, not much. Mike himself would never get used to it personally, but he knew that Germans of the 17 th century were accustomed to a level of population density in their living arrangements that would drive most Americans half-crazy. A good bed was valuable-why waste it on two people, when four would fit?

Once the door was closed, he cocked an eyebrow at Nichols. Trying, probably with not much success, to keep his worry hidden.

No success at all, apparently:

"It's not plague, if that's what you're worrying about." James' voice was more gravelly than usual. Nichols worked long hours as a matter of routine. But Mike knew that since Melissa had left Grantville, he practically lived at the hospital. Insofar as a black man's face could look gray with fatigue, James' did. His hard and rough features seemed a bit softer, not from warmth but simply from weariness.

"You need to get some sleep yourself," said Mike sternly.

James gave him a smile which was half-mocking. "Oh, really? And exactly how much sleep have

As they continued moving down the corridor toward Nichols' office, weaving their way through the packed halls of Grantville's only hospital, James' scowl returned in full force.

"What in God's name possessed us to send our womenfolk off into that howling wilderness?" he demanded. Indicating, with a sweep of the hand, everything in the world.

Mike snorted. "Paris and London hardly qualify as 'howling wilderness,' James. I'm sure James Fenimore Cooper would agree with me on that, once he gets born. So would George Armstrong Custer."

"Bullshit," came the immediate retort. "I'm not an 'injun-fighter,' dammit, I'm a doctor. Cities in this day and age are a microbe's paradise. It's bad enough even here in Grantville, with our-ha! what a joke!-so-called 'sanitary practices.' "

They'd reached the doctor's office and, once again, Mike opened for James. "Forget 'gay Paree,' Mike. In the year of our Lord 1633, the sophisticated Parisian's idea of 'sanitation' is to look out the window first before emptying the chamber pot."

The image made Mike grimace a little, but he didn't argue the point. He'd be arguing soon enough, anyway, he knew. James' wisecrack about Grantville's sanitation was bound to be the prelude to another of the doctor's frequent tirades on the subject of the lunacy of political leaders in general, and those of the Confederated Principalities of Europe in particular. Which, of course, included Mike himself.

Once they'd taken their seats-James behind the desk and Mike in front of it-he decided to intersect the tirade before it even started.

"Don't bother with the usual rant," he growled. His own voice sounded pretty gravelly itself, and he reminded himself firmly not to take his own grouchiness at Rebecca's absence out on Nichols. For all that the doctor's near-monomania on the subject of epidemics sometimes irritated Mike, he respected and admired Nichols as much as he did anyone he'd ever met. Even leaving aside the fact that James had become one of his best friends since the Ring of Fire, the doctor's skill and energy was all that had kept hundreds of people alive. Probably thousands, when you figured in the indirect effects of his work.

"What's she got?" he asked gruffly. "Another case of the flu?"

Nichols nodded. "Most likely. Could be something else-more precisely,

"Any luck with-"

James shrugged. "Jeff Adams thinks we'll have a vaccine ready to go within a month or so, in large enough quantities to make a difference. I just hope he's right that using cowpox will work. Me, I'm a little skeptical. But…"

Suddenly, he grinned. The expression came more naturally to James Nichols' face than did the scowl which usually graced it these days. "You'd think, wouldn't you, that a boy from the ghetto would be less fastidious than you white folks! But, I ain't. God, Mike, talk about the irony of life. I can remember the days when I used to complain, back in my ghetto clinic, that I was mired in the Dark Ages. And here I am-mired in the

"Don't ever let Melissa hear you say that," responded Mike, grinning himself. "Talk about a tirade!"

James sniffed. "Fine for her to lecture everybody on the upstanding qualities of people in all times and places. She was brought up a Boston Brahmin. Probably got fed political correctness with her formula. Me, I grew up in the streets of south Chicago, and I know the truth. Some people are just plain rotten, and most people are lazy. Careless, anyway."

He heaved himself erect from his weary sprawl in the chair, and leaned over the desk, supporting his weight on his arms. "Mike, I'm really

He jerked a thumb toward the window. Beyond it lay the town of Grantville.

"What's the point of lecturing people every night on the TV programs about the need for personal sanitation-when most of them can't afford a change of clothes? What are they supposed to do-in the middle of Germany, in winter-walk around naked while they stand in line at the town's one and only public laundry worth talking about?"

There wasn't any trace of the grin left, now. "While we devote our precious resources to building more toys for that fucking king, instead of a textile and garment industry, the lice are having a field day. And I will

Mike sat up himself. The argument was back, and there was no point in trying to evade it. James Nichols was as stubborn and tenacious as he was intelligent and dedicated. The fact that Mike was at least half in agreement with the doctor just made him all the more stubborn in defending Gustavus Adolphus-and, of course, his own policies. The United States of which Mike Stearns was President was, on one level, just another of the many principalities which formed the Confederated Principalities of Europe under the rule of the king of Sweden. Even if, in practice, it enjoyed a status of near-sovereignty.

"James, you can't reduce this to simple arithmetic. I

He leaned back, sighing heavily. "What do you want me to do, James? For all his prejudices and quirks and godawful attitudes on a lot of questions, Gustavus Adolphus is the best ruler of the times. You don't doubt that any more than I do. Nor do you think, any more than I do, that Grantville could make it on its own-without devoting even

He lurched to his feet and took three strides to the window. There, he glowered down at the scene. Nichols' office was on the top floor of the three-story hospital, giving him a good view of the sprawling little city below.

And "sprawling" it was. Sprawling, and teeming with people. The sleepy little Appalachian town which had come through the Ring of Fire two years earlier was long gone, now. Mike could still see the relics of it, of course. Like most small towns in West Virginia, Grantville had suffered a population loss over the decades before the Ring of Fire. Downtown Grantville had some large and multi-story buildings left over from its salad days as a center of the gas and coal industry. On the day before the mysterious and still-unexplained cosmic disaster which had transplanted the town into 17 th -century Europe, those buildings had been half vacant. Today, they were packed with people-and new buildings, well if crudely built, were rising up all over the place.

The sight caused him to relax some. Whatever else he had done, whatever mistakes he might have made, Mike Stearns and his policies had turned Grantville and the country surrounding it into one of the few areas in central Europe which were economically booming and had a growing population. A rapidly growing one, in fact. If Mike's insistence on supporting Gustav Adolf's armaments campaign would result in the death of many people-which it would; he didn't doubt that any more than Nichols did-it would keep many more alive. Alive, and prospering.

Such, at least, was his hope.

"What am I supposed to do, James?" he repeated, softly rather than angrily. "We're caught in a three-way vise-and only have two hands to fend off the jaws."

Without turning away from the window, he held up a finger.

"Jaw number one. Whether we like it or not, we're in the middle of one of the worst wars in European history. Worse, in a lot of ways, than either of the world wars of the twentieth century. With no sign that any of the great powers that surround us intend to make peace."

He heard a little throat-clearing sound behind him, and shook his head. "No, sorry, we haven't heard anything from Rita and Melissa yet. I'd be surprised if we had, since they and Julie and Alex were planning to sail from Hamburg. But I did get a radio message from Becky yesterday. She arrived in Paris a few days ago and is already leaving for Holland."

He heard James sigh. "Yeah, you got it. Richelieu was polite as could be, but hasn't budged an inch. In fact, Becky thinks he's planning some kind of new campaign. If she's right, knowing that canny son-of-a-bitch, it's going to be a doozy."

He looked toward the south. "Then, of course, we've still got the charming Austrian Habsburgs to deal with. Not to mention Maximilian of Bavaria. Not to mention that Wallenstein survived his wounds at the Alte Veste and God only knows what that man is really cooking up on his great estates in Bohemia. Not to mention that King Christian of Denmark-Protestant or not-is still determined to bring down the Swedes. Not to mention that most of Gustav's 'loyal princes'-Protestant or not-are the sorriest pack of treacherous scumbags you'll ever hope to meet in your life."

Mike started tapping his fingers on the pane. "So that's the first jaw. We're in a war, whether we like it or not. If anything, I think the war is starting to heat up again.

"Which brings us to 'jaw number two.' How should we fight it? The same way Gustav's been doing since he landed in northern Germany three years ago? With huge mercenary armies draining the countryside? Even leaving aside any outrages they commit on the civilian population-and they do, even with Gustav's disciplinary policies, don't think they don't-it's the stupidest waste of economic resources imaginable. It's already bled Sweden of too many able-bodied men, and left Gustav's treasury dry as a bone."

His fingers moved. Tap, tap, tap; like a drummer beating the march. "We can't keep borrowing money forever, James. The Abrabanels and the other Jewish financiers in Europe and Turkey who are backing us aren't really all

He turned his head and returned James' glare with one of his own. "They won't be able to afford another change of clothes either

Nichols looked away, his face sagging a little. James was by no means stupid, however strongly he felt about his own concerns.

Mike drove on relentlessly. "So what's the alternative-besides John Simpson's 'new military policy'?"

The mention of Simpson brought a fierce scowl to Nichols' face. Mike barked a laugh-even though, as a rule, the name "John Simpson" usually brought a scowl to his own face.

"Yeah, sure. The man is an unmitigated ass. Arrogant, supercilious, about as caring as a stone, you name it. What's that paraphrase from Gilbert and Sullivan that Melissa uses? 'The very picture of a modern CEO?' "

James nodded, chuckling. The doctor's lover despised John Simpson even more than he and Mike did.

Mike shrugged. "But whatever else he is, John Simpson is also the only experienced military officer in Grantville. On that level of experience, anyway. He

Mike planted his hands on the windowsill and pushed himself away. Then, went back and sat down again.

"Look, James, on this subject Simpson is right

He sighed, and rubbed his face. "And that, of course, brings us right up against 'jaw number three.' Because those same resources being used to build Gustav's 'toys,' as you call them, aren't being used to develop other things. Such as really pushing a textile industry, or throwing the weight we ought to be throwing behind the small motor industry-farmers need a lot of little ten-horsepower engines, not a handful of diesel monsters driving a few ironclads-or damn near anything else you can think of."

For a moment, he and James stared at each other. Then, shrugging again, Mike added: "What the hell, look on the bright side. If nothing else, the economic and technical crunch is making everybody think

The word "organize," inevitably for a man brought up in the trade-union movement, brought the first genuine smile to Mike's face. "Don't underestimate that, James, not for a minute. We may be a sorry lot of filthy disease-carriers, but I can guarantee

He waved his hand in a gesture which was as broadly encompassing as the one James had used earlier. But vigorous, where the doctor's had been despairing.

"You name it, we've got it. Trade unions spreading all over the place, farmers' granges, Willie Ray's kids in his Future Farmers of Europe spending as much time arguing politics as they do seeds, Gretchen's fireballs in the Committees of Correspondence. Damned if even the old boys' clubs aren't alive and kicking and talking about something other than their silly rituals. Henry Dreeson told me that his Lions club voted last week to start making a regular donation to the Freedom Arches Foundation."

James' eyes practically bulged. Somehow-to this day nobody knew exactly how she'd managed it-Gretchen had gotten the former McDonald's franchise hamburger stand in Grantville turned over to her Committees of Correspondence. (The manager of the restaurant, Andy Yost, swore he knew nothing about it-but he'd stayed on as manager, nonetheless, and-pure coincidence, perhaps-was on the Steering Committee of Gretchen's rapidly growing band of radicals.)

Gretchen had promptly renamed it the "Freedom Arches," and the former McDonald's had instantly become the 17 th -century's equivalent of the famous bistros and coffee houses of the revolutionary Paris of a later era. Moving with their usual speed and energy, the Committees of Correspondence had begun creating other franchises patterned after it in every town in the United States-and beyond. A new "Freedom Arches" had been erected just outside the boundaries of Leipzig, the nearest big city in Saxony. Much to the displeasure of John George, the prince of Saxony, who had immediately complained to Gustav Adolf. But the king of Sweden, who was also the emperor of the Confederated Principalities of Europe, had refused to direct its dismantling. Gustav had his own reservations-to put it mildly-about the Committees of Correspondence. But he was no fool, and had learned the principle of keeping aristocrats under a tight rein from his own Vasa dynasty's history. The Committees made him nervous, true; but they terrified such men as John George of Saxony, which was even better.

The buildings in which the new "Freedom Arches" sprang up were themselves 17 th -century construction, of course. But the two arches which prominently advertised them, even if they were painted wood instead of fancy modern construction, would have been recognized by any resident of the United States in the America which had been left behind. Granted, once they went through the doors, the average 21 st -century American would have been puzzled by what they saw. The food served was more likely to be simple bread than anything else, with tea and beer for beverages instead of coffee. And they'd

"The

Mike grinned. "Yup. They're keeping it quiet, of course. Give them some credit, James. Sure, Gretchen and her firebrands make them twitchy, but even the town's stodgiest businessman knows we're in a fight for our lives. The Knights of Columbus aren't even trying to keep quiet about their own donations. As Catholics, they're determined to prove as publicly as possible that they're the most loyal citizens around."

James grunted. In the sometimes bizarre way that history works, the officially Protestant Confederated Principalities of Europe-in that portion of it under U.S. jurisdiction, with its rigorously applied principles of freedom of religion-had become a haven for central Europe's Catholics. By now, between the influx of immigrants and the incorporation of western Franconia after the victory of Gustav and his American allies over the Habsburgs at the battle of the Alte Veste, the majority of the population of the United States might well be Catholic. Catholics were certainly approaching parity with the Protestant population-and, typically, were even more devoted to its (by European standards of the day) radical political principles.

Mike spread his hands. "So, like I said, look on the bright side. We're buying time, James. I know as well as you do that we could get struck by an epidemic. But, if we do, we'll at least be able to deal with the crisis with a population that's alert, getting better organized by the day, and is probably already better educated than any other in Europe outside of maybe Holland."

"I still don't see the logic of devoting so much of our resources-military ones, I'm talking about-to those ironclads Simpson is gung-ho about," said James sourly. "Those things are a damn 'resource sink.' Leaving aside all the good steel we had to turn over-I can think of better things to do with miles of steel rails left over from the Ring of Fire than just using them for armor-we had to cannibalize several big diesel engines, the best pumps in the mine…"

He trailed off. "Okay, I grant you, I wasn't at the cabinet meeting where the decision was made, since I was in Weimar dealing with that little outbreak of dysentery-at least

Mike pursed his lips and stared out the window. He wasn't surprised his synopsis of the logic hadn't made a lot of sense to James, at the time. That was because it really

Mike hesitated. He was reluctant to get into the subject, because the

Nichols, as a doctor-even leaving aside his romantic involvement with Melissa-would be just as likely to choke. Especially given that, unlike many doctors Mike had known in his life, James Nichols took his profession as a

On the other hand…

Mike studied James for a moment. The rough-featured, very dark-skinned black man returned his gaze stonily, his hands clasped on the desk in front of him. There were scars on those hands which hadn't come from medical practice. Before Nichols turned his life around, he'd grown up as a street kid in one of the toughest ghettoes in Chicago. Blackstone Rangers territory that had been, in his youth.

"All right, James, I'll give it to you straight. The reason Gustav Adolf wants those ironclads is in order to secure his logistics routes in case the CPE is attacked from without. In this day and age, military supplies can be transported by water far more easily than any other way. If he can control the rivers-the Elbe, first and foremost, but also the smaller ones and the canals, especially as we keep improving them-then he's got a big edge against anyone trying to invade. But that's only part of it, and not the most important part."

He sat up straight. Harshly: "The more important reason is because he needs them-or, at least, thinks he might-in order to hold the CPE together in the first place."

Nichols' eyes widened slightly. Slightly, but… not much.

"Think about it, for Pete's sake," Mike continued. He waved his hand at the window. "The Confederated Principalities of Europe is the most ramshackle, patched-together, jury-rigged so-called

Nichols snorted. "Would take bets on how deep the stab wound went. And then start quarreling over who got to hold the money."

"Exactly. The whole thing could fly apart in an instant. So. Consider how the situation looks from the

He smiled wolfishly. "Consider, for instance, the Finow canal which connects the Elbe and the Havel and the Oder-which, as you may know, is one of the ones Gustav has prioritized for rebuilding and upgrading. Second only, in fact, to the canals connecting the Elbe to the Baltic ports of Luebeck and Wismar. Consider what things will look like

"They could wreck the canals," protested James. "Destroy the locks, at least." But the protest was half-hearted.

Mike shrugged. "Easier said than done, James, and you know it as well as I do. With a good engineering corps-and Gustav has the best-they can be rebuilt. Besides, that all presupposes a bold and daring and well-coordinated uprising on the part of several princes acting in unison. Which-"

James was already chuckling. "

Mike shared in the humor. Within a few seconds, though, James was no longer smiling. Instead, he was giving Mike a somewhat slit-eyed stare. "Are you

Mike shrugged. "Yeah, I am. Like I said, James, I'm buying us time. And buying it for Gustav Adolf, too, because-for quite a while, at least-our fortunes are tied to his."

Nichols lowered his clasped hands into his lap, rocked back his chair, and gave Mike a thin smile. "You'd have probably done pretty good, you know, down there around Sixty-Third and Cottage Grove. Of course, your skin color would have been a handicap. But, if I know you, you'd have figured out some way around that too."

Mike's smile didn't waver. "Under the circumstances, I think I'll take that as a compliment."

Nichols snorted. "Under the circumstances, it

Silence fell in the room. James' face was still tight with concern, but, after a moment, Mike realized that the man's concern had moved from general affairs to the point nearest to his heart.

"I'll send word as soon as I hear from her," Mike said softly. "She'll be all right, James. I gave Rita and Melissa enough money to hire a

James smiled. Julie Sims-Julie Mackay, now, since her marriage to a Scot cavalry officer in Gustav Adolf's army-was the best rifle shot anyone had ever met. And whatever James and Mike thought of John Simpson, both of them approved highly of Simpson's son Tom, who had married Mike's sister on the same day the Ring of Fire changed their entire world. Especially under these circumstances. Whatever other dangers James' lover Melissa and Mike's sister Rita would face in their diplomatic mission to England, they were hardly likely to be pestered by footpads. Tom Simpson was quite possibly one of the ten biggest men in the world. He'd been something of a giant even in 21 st -century America, with the shoulders and physique you'd expect from a lineman on a top college football team.

But the doctor's smile faded soon enough. Mike knew he wasn't really worried-not much, anyway-about pirates and footpads. Melissa and Rita would be dealing with people a lot more dangerous than that.

"Kings and princes and cardinals and God-help-me dukes and fucking earls," grumbled Nichols. "Oughta shoot the whole lot of 'em."

Mike's grin was probably a little on the merciless side. He certainly intended it to be, seeing as how the doctor needed to be cheered up. "We might yet. A fair number of them, anyway. Like I said, look on the bright side. Simpson may be an asshole, but he knows his big guns."

Chapter 4

The noise, as always, was appalling.

John Chandler Simpson had grown accustomed to it, although he doubted he was ever going to truly get used to it. Of course, there was a lot he wasn't going to get used to about the Year of Our Lord 1633.

He snorted sourly at the thought as he waded through another of the extensive mud puddles which made trips to the dockyard such an… adventure. There'd been a time when he would have walked around the obstacle, but that had been when he'd still had 21st-century shoes to worry about. And when he'd had the energy to waste on such concerns.

He snorted again, even more sourly. He supposed he ought to feel a certain satisfaction at the way that asshole Stearns had finally been forced to admit that he knew what he was talking about where

Not that Stearns was a complete idiot, he admitted grudgingly. At least he'd had the good sense to recognize that Simpson was right about the need to "downsize" Gustavus Adolphus' motley mercenary army. Oh, how the President had choked on that verb! It had almost been worth being forced to convince him of anything in the first place. And even though he'd accepted Simpson's argument, he hadn't wanted to accept the corollary-that if Gustavus Adolphus was going to downsize, it was up to the Americans to make up the difference in his combat power… even if that meant diverting resources from some of the President and his gang's pet industrialization projects.

Still, Simpson conceded, much as it irritated him to admit it, Stearns had been right about the need to increase their labor force if they were going to make it through that first winter. Which didn't mean he'd found the best way to do it, though, now did it?

Things had worked out better-so far, at least-than Simpson had feared they would when he realized where Stearns was headed with his new Constitution. There was no guarantee it would stay that way, of course. Under other circumstances, Simpson would probably have been amused watching Stearns trying to control the semi-anarchy he'd forged by bestowing the franchise over all of the local Germans and their immigrant cousins and in-laws as soon as they moved into the United States' territory. The locals simply didn't have the traditions and habits of thought to make the system work properly as it had back home. They thought they did, but the best of them were even more addicted to sprawling, pressure cooker bursts of unbridled enthusiasm than Stearns and his union blockheads. And the lunatic fringe among them-typified by Melissa Mailey's supporters and Gretchen Higgins' Committees of Correspondence-were even worse. There was no telling what kind of disaster they might still provoke. All of which could have been avoided if the hillbillies had just had the sense to limit the franchise to people who had demonstrated that they could handle it.

The familiar train of thought had carried him to the dockyard gate, and he looked up from picking his way through the mud as the double-barrel-shotgun-armed sentry came to attention and saluted. Like the vast majority of the United States Army's personnel, the sentry was a 17 th -century German. Which was all to the good, Simpson reflected, as he returned his salute. The casual attitude the original Grantville population-beginning with "General" Jackson himself-brought to all things military was one of the many things Simpson detested about them. None of them seemed to appreciate the critical importance of things like military discipline, or the way in which the outward forms of military courtesy helped build it. The local recruits hadn't had much use for the niceties of formal military protocol, either, but at least any man who had survived in the howling chaos of a 17 th -century battlefield understood the absolute necessity for iron discipline. Off the field, they might be rapists, murderers, and thieves; on the field was something else again entirely, and it was interesting how eagerly the 17 th -century officers and noncoms had accepted the point Simpson's up-time compatriots seemed unable to grasp, however hard he hammered away at it. The habit of discipline had to be acquired and nurtured off the field as much as on it if you wanted to create a truly professional, reliable military force. That, at least, was one point upon which he and Gustavus Adolphus saw completely eye to eye.

He returned the sentry's salute and continued onward into the dockyard, then paused.

Behind him lay the city of Magdeburg, rising from the rubble of its destruction in a shroud of dust, smoke, smells, shouts, and general bedlam. Some of that construction was traditional Fachwerk or brick construction on plots for which heirs had been located; intermixed with balloon frames and curtain walls on lots that had escheated into city ownership. Before him lay the River Elbe and another realm of swarming activity. It was just as frenetic and even noisier than the chaotic reconstruction efforts at his back, but he surveyed it with a sense of proprietary pride whose strength surprised even him just a bit. Crude and improvised as it was compared to the industrial enterprises he had overseen back home, it belonged to him. And given what he had to work with, what it was accomplishing was at least as impressive as the construction of one of the Navy's

An earsplitting racket, coal smoke, and clouds of sawdust spewed from the steam-powered sawmill Nat Davis had designed and built. The vertical saw slabbed off planks with mechanical precision, and the sawmill crew heaved each plank up into the bed of a waiting wagon as it fell away from the blade. The sawmill was a recent arrival, because they had decided not to waste scarce resources on intermediate construction of a water- or windmill that would just end up being dismantled again. Only two weeks ago, the men stacking those planks had been working hip deep in cascading sawdust in an old-fashioned saw pit, laboriously producing each board by raw muscle power.

Beyond the sawmill, another crew labored at the rolling mill powered by the same steam engine. The mill wasn't much to look at compared to the massive fabricating units of a 21 st -century steel plant, but it was enough to do what was needed. Simpson watched approvingly as the crew withdrew another salvaged railroad rail from the open furnace and fed it into the rollers. The steel, still smoking and red hot from its stay in the furnace, emerged from the jaws of the mill crushed down into a plank approximately one inch thick and a little over twelve inches wide. As it slid down another set of inclined rollers, clouds of steam began rising from the quenching sprays. More workmen were carrying cooled steel planks to yet another open-fronted shed, where one of the precious gasoline-powered portable generators drove a drill press. The soft whine of the drill bit making bolt holes in the steel was lost in the general racket.

Simpson stood for a moment, watching, then nodded in satisfaction and continued toward his dockside office. It was nestled between two of the slipways, in the very shadow of the gaunt, slab-sided structures looming above it. They were ugly, unfinished, and raw, and even when they were completed, no one would ever call them graceful. But that was fine with John Simpson. Because once they were finished, they were going to be something far more important than graceful.

Another sentry guarded the office door and came to attention at his approach. Simpson returned his salute and stepped through the door, closing it behind him. The noise level dropped immediately, and his senior clerk started to come to his feet, but Simpson waved him back into his chair.

"Morning, Dietrich," he said.

"Good morning, Herr Admiral," the clerk replied.

"Anything important come up overnight?" Simpson asked.

"No, sir. But Herr Davis and Lieutenant Cantrell are here."

The clerk's tone held an edge of sympathy and Simpson grimaced. It wasn't something he would have let most of his subordinates see, whatever he might personally think of a visitation from that particular pair. Demonstrating any reservations he might nurse about them openly could only undermine the chain of command he'd taken such pains to create in the first place.

But Dietrich Schwanhausser was a special case. He might be yet another German, but he was worth his weight in gold when it came to administration. He'd also taken to the precious computer sitting on his desk like one of those crazed 21 st -century teenagers… and without the attitude. That combination, especially with his added ability to intelligently anticipate what Simpson might need next, had made him an asset well worth cultivating and nurturing. Simpson had recognized that immediately, but he was a bit surprised by the comfort level of the relationship they had evolved.

"Thanks for the warning," he said wryly, and Schwanhausser's lips twitched on the edge of a smile. Simpson nodded to him and continued on into the inner office.

It was noisier than the outer office, because unlike Schwanhausser's space, it actually had a window, looking out over the river. The glass in that window wasn't very good, even by 17 th -century standards, but it still admitted natural daylight as well as allowing him a view of his domain. And the subtle emphasis of the status it lent the man whose wall it graced was another point in its favor.

Two people were waiting when he stepped through the door. Nat Davis was a man in his forties, with blunt, competent workman's hands, a steadily growing bald spot fringed in what had once been dark brown hair, and glasses. Prior to the Ring of Fire, he'd been a tobacco chewer, although he'd gone cold turkey-involuntarily-since Grantville's arrival in Thuringia. That habit, coupled with a strong West Virginia accent and his tendency to speak slowly, choosing his words with care, had caused Simpson to underestimate his intelligence at first. The Easterner had learned better since, and he greeted the machinist with a much more respectful nod than he might once have bestowed upon him.

The young man waiting with Davis was an entirely different proposition. Eddie Cantrell was still a few months shy of his twentieth birthday, and he might have been intentionally designed as Davis' physical antithesis.

The older man was stocky and moved the same way he talked, with a sort of thought-out precision which seemed to preclude any possibility of spontaneity. That ponderous appearance, Simpson had discovered, could be as deceiving as the way he chose his words, but there was nothing at all deceptive about the sureness with which Davis moved from one objective to another.

Spontaneity, on the other hand, might have been Eddie Cantrell's middle name. He was red-haired and wiry, with that unfinished look of hands and feet that were still too large for the rest of him, and the entire concept of discipline was alien to his very nature. Worse, he bubbled. No, he didn't just "bubble." He boiled. He

All of which made it even more surprising to Simpson that he'd actually come to

Not that he had any intention of telling him so.

"Good morning, gentlemen," he greeted them as he continued across the cramped office confines to his desk. He settled himself into his chair and tipped it back slightly, the better to regard them down the length of his nose. "To what do I owe the pleasure?"

Davis and Cantrell looked at one another for a moment. Then Davis shrugged, smiled faintly, and made a tiny waving motion with one hand.

"I guess I should go first… sir," the younger man said. The hesitation before the "sir" wasn't the deliberate pause it once might have been. Simpson was relatively confident of that. It was just one more indication of how foreign to Eddie's nature the ingrained habits of military courtesy truly were.

"Then I suggest you do so… Lieutenant." Simpson's pause

"Yes, sir." Eddie gave himself a little shake. "Matthias just reported in. He says that Freiherr von Bleckede is being, um, stubborn."

"I see." Simpson tipped his chair back a bit farther and frowned. Matthias Schaubach was one of the handful of Magdeburg's original burghers to have survived the massacre of the city's inhabitants by Tilly's mercenaries. Prior to that traumatic event, he'd been deeply involved in the salt trade up and down the Elbe from Hamburg, which had made him the Americans' logical point man on matters pertaining to transport along the river.

The Elbe, for all its size and importance to northern Germany, was little more than a third as long as the Mississippi. By the time it reached Magdeburg, over a hundred and sixty air-miles from Hamburg, whether or not it could truly be called "navigable" was a debatable point. Barge traffic was possible, but the barges in question averaged no more than forty feet in length, which was much smaller than anything the Americans would need to get downriver. Some improvements to navigation had been required even to get the barges through, and it was obvious to everyone that even more was going to be necessary shortly.

For the past several weeks, Schaubach had been traveling up and down the Elbe discussing that "even more" with the locals. The existing network of "

Most of the

Some of them, however, were more stubborn than others. Like the petty baron Freiherr von Bleckede. A part of Simpson actually sympathized with the man, not that it made him any happier about Eddie's news.

"I take it Mr. Schaubach wouldn't have reported it if he thought he was going to be able to change Bleckede's mind?" he said after a moment.

"It doesn't sound like he's going to be able to," Eddie agreed. He made a face. "Sounds to me like von Bleckede doesn't much care for us. Or the Swedes, either."

"I'm not surprised," Simpson observed. "Hard to blame him, really." He smiled blandly as an expression of outrage flickered across Eddie's face. He considered enlarging upon his theme. It wouldn't do a bit of harm to remind Eddie that the pre-Ring of Fire establishment had a huge number of reasons to resent and fear the upheavals in the process of tearing the

"Well," Cantrell said more than a little impatiently, as if to prove Simpson's point for him, "whether we blame him for it or not, we still need to get clearance for the crews to go to work on his

"No, it isn't," Simpson agreed. He was careful not to let it show, but privately he felt a small flicker of pleasure at Eddie's reference to the trim tanks. The entire ironclad project had originated with Eddie's war-gaming hobby interest. He was the one who'd piled his reference books up on the corner of Mike Stearns' desk and sold him on the notion of armed river steamboats to police their communications along the rivers. Of course, his original wildly enthusiastic notions had required the input of a more adult perspective, but the initial concept when authorization of the project was first discussed had reflected his ideas of how best to update a design from the American Civil War. By Simpson's most conservative estimate, there hadn't been more than two or three dozen things wrong with it… which was only to be expected when a hobby enthusiast set out to transform his war-gaming information into reality.

Eddie's design, once Simpson and Greg Ferrara finished their displacement calculations, would have drawn at least twelve feet at minimum load. That draft would have been too deep even for the Mississippi, much less the Elbe. It also would have been armored to resist 19 th -century artillery, like the Civil War's fifteen-inch smoothbores, rather than the much more anemic guns of the 17 th century. Worse than that, Eddie had called for a single-screw design. His otherwise praiseworthy objective had been to save the huge bulk of a paddle wheel housing, which would not only have cut down on places to mount armament but required an even bigger investment in armor. Given that they'd had to fight people like Quentin Underwood tooth and nail for every salvaged railroad rail dedicated to the project, that hadn't been an insignificant consideration.

Unfortunately, marine screw propellers were much more difficult to design properly than Eddie had imagined. Simpson knew that; his last assignment before the Pentagon had been as a member of the design group working on the propulsion systems for the

Which was why Simpson had bullied Stearns into letting him have the diesel power plants out of four of the huge coal trucks which had originally been used as armored personnel carriers. Fuel for the APC engines, though scarce, was still available, and once Underwood got the kinks out of his oil-field production, scarcity wouldn't be a problem. Not with the priority Stearns had agreed to assign to the Navy, at any rate.

With the engines figuratively speaking in hand, Simpson had created a highly modified version of Eddie's original concept-one which used powerful diesel-driven pumps scavenged from the Grantville coal mine to provide hydro-jet propulsion. The pumps were powerful enough to chew up most small debris without damage, and screens across the intakes protected them from anything larger. Using the diesels would increase the gunboats' logistic dependency on the Grantville industrial base, since it wouldn't be possible to fuel them with coal or wood in an emergency, as would have been possible with a steam-powered engineering plant. On the other hand, the diesel bunkers could be safely located below the water line, and at least if a freak hit managed somehow to penetrate to one of the ironclads' interiors, there would be no handy boiler full of live steam to boil a crew alive.

The other two things he'd done to Eddie's original design were to cut the armor thickness in half and add the trim tanks. Reducing the armor had let him squeeze an additional ship out of the rails allocated to the project, as well as saving displacement, but the tanks were at least as important. The original

At first, Eddie had been inclined to sulk when Simpson modified his basic design. To his credit, he'd recognized that the alterations were genuine improvements, and that was the reason Simpson (although he doubted that the young man was aware of it) had specifically requested that he be assigned to the Navy. Stearns had already sent him to Magdeburg to help oversee the project, after all, which meant Simpson couldn't have gotten rid of him, anyway. And the Navy was going to need officers who could actually

And if it had also let Simpson get the last laugh on Mike Stearns, so much the better.

"Fortunately," he went on after a moment, "convincing the freiherr to go along with our plans isn't really our concern. If Mr. Schaubach feels that he's unlikely to be able to get von Bleckede to see reason, refer him to Mr. Piazza." He smiled again, more blandly than ever, as Eddie frowned. Ed Piazza, the secretary of state, had been Stearns' choice to serve as his personal representative to all the various minor local potentates not worthy of the personal attention of the head of state.

"That will take time," Eddie began, "and-"

"That may be true," Simpson interrupted. "But it's the secretary of state's job to deal with things like this. Or let Gustav's chancellor Oxenstierna deal with it. We've got more to worry about than convincing one minor nobleman to see things our way. Besides, whether we like it or not, we've

Eddie looked rebellious, but Simpson was accustomed to that. What mattered more to him was the fact that the youngster actually thought his way through it, then subsided with nothing more than one last grimace.

"Now," Simpson went on, "was there anything else you needed, Lieutenant?"

"No, I guess not… sir."

"Good." Simpson turned to Davis. "And what can I do for you, Mr. Davis?" he asked.

"Actually," Davis replied, "I just wanted to let you know that Ollie says he should have the first half dozen gun tubes ready to ship to us by the end of the week."

"Good!"

Simpson was unaware of the way in which his genuine enthusiasm transfigured his own expression. The change was brief, but Davis recognized it. It was a pity, he often thought, that Simpson had such a completely tone deaf "ear" where minor things like interpersonal relations were concerned. Personally, Davis still thought the man was a prick, especially as far as politics went, and he didn't much care for the "admiral's" obsession with matters of rank-social, as well as military-and the perquisites which went with it. But he'd come to recognize that however unpleasant Simpson's personality might be, the man undeniably had a brain. Quite a good one, as a matter of fact, when it could be pried away from things like his political disagreements with Mike Stearns.