"Anathem" - читать интересную книгу автора (Stephenson Neal)

Part 5

VOCO

Whatever you might say of his rich descendants, Fraa Shuf had had little wealth and no plan. That became obvious as soon as you descended the flagstone stairs into the cellar of the place that he had started and his heirs had finished. I write

Anyway, by the time that the Reformed Old Faanians had begun sneaking back to the ruin of Shuf’s Dowment, hundreds of years after the Third Sack, the earth had reclaimed much of the cellars. I wasn’t sure how the dirt got into those places and covered the floor so deep. Some process humans couldn’t fathom because it went on so gradually. The ROF, who had been so diligent about fixing up the above-ground part, had almost completely ignored the cellars. To your right as you reached the bottom of the stairs there was one chamber where they stored wine and some silver table-service that was hauled out for special occasions. Beyond that, the cellars were a wilderness.

Arsibalt, contrary to his reputation, had become its intrepid explorer. His maps were ancient floor-plans that he found in the Library and his tools were a pickaxe and a shovel. The mystical object of his quest was a vaulted sub-basement that according to legend was where Shuf’s Lineage had stored its gold. If any such place had ever existed, it had been found and cleaned out during the Third Sack. But to rediscover it would be interesting. It would also be a boon for the ROF since, in recent years, avout of other orders had entertained themselves by circulating rumors to the effect that the ROF had found or were accumulating treasure down there. Arsibalt could put such rumors to rest by finding the sub-basement and then inviting people to go and see it for themselves.

But there was no hurry—there never was, with him—and no one was expecting results before Arsibalt’s hair had turned white. From time to time he would come tromping back over the bridge covered with dirt and fill our bath with silt, and we would know he had gone on another expedition.

So I was surprised when he took me down those stairs, turned left instead of right, led me through a few twists and turns that looked too narrow for him, and showed me a rusty plate in the floor of a dirty, wet-smelling room. He hauled it up to expose a cavity below, and an aluminum step-ladder that he had pilfered from somewhere else in the concent. “I was obliged to saw the legs off—a little,” he confessed, “as the ceiling is quite low. After you.”

The legendary treasure-vault turned out to be approximately one arm-span wide and high. The floor was dirt. Arsibalt had spread out a poly tarp so that perishable things—“such as your bony arse, Raz”—could exist here without continually drawing up moisture from the earth. Oh, and there wasn’t any treasure. Just a lot of graffiti carved into the walls by disappointed slines.

It was just about the nastiest place imaginable to work. But we had almost no choices. It wasn’t as if I could sit up on my pallet at night and throw my bolt over my head like a tent and stare at the forbidden tablet.

We employed the oldest trick in the book—literally. In the Old Library, Tulia found a great big fat book that no one had pulled down from the shelf in eleven hundred years: a compendium of papers about a kind of elementary particle theorics that had been all the rage from 2300 to 2600, when Saunt Fenabrast had proved it was wrong. We cut a circle from each page until we had formed a cavity in the heart of this tome that was large enough to swallow the photomnemonic tablet. Lio carried it up to the Fendant court in a stack of other books and brought it back down at suppertime, much heavier, and handed it over to me. The next day I gave it to Arsibalt at breakfast. When I saw him at supper he told me that the tablet was now in place. “I looked at it, a little,” he said.

“What did you learn?” I asked him.

“That the Ita have been diligent about keeping Clesthyra’s Eye spotless,” he said. “One of them comes every day to dust it. Sometimes he eats his lunch up there.”

“Nice place for it,” I said. “But I was thinking of night-time observations.”

“I’ll leave those to you, Fraa Erasmas.”

Now I only wanted an excuse to go to Shuf’s Dowment a lot. Here at last politics worked in my favor. Those who looked askance at the ROF’s fixing up the Dowment did so because it seemed like a sneaky way of getting something for nothing. If asked, the ROF would always insist that anyone was welcome to go there and work. But New Circles and especially Edharians rarely did so. Partly this was the usual inter-Order rivalry. Partly it was current events.

“How have your brothers and sisters been treating you lately?” Tulia asked me one day as we were walking back from Provener. The shape of her voice was not warm-fuzzy. More curious-analytical. I turned around to walk backwards in front of her so that I could look at her face. She got annoyed and raised her eyebrows. She was coming of age in a month. After that, she could take part in liaisons without violating the Discipline. Things between us had become awkward.

“Why do you ask? Just curious,” I said.

“Stop making a spectacle of yourself and I’ll tell you.”

I hadn’t realized I was making a spectacle of myself but I turned back around and fell in step beside her.

“There is a new strain of thought,” Tulia said, “that Orolo was actually Thrown Back as retribution for the politicking that took place during the Eliger season.”

“Whew!” was the most eloquent thing I could say about that. I walked on in silence for a while. It was the most ridiculous thing I’d ever heard. If you couldn’t be Thrown Back for stealing mead and selling it on the black market to buy forbidden consumer goods, then what

“Ideas like that are evil,” I said, “because some creepy-crawly part of your brain wants to believe in them even while your logical mind is blasting them to pieces.”

“Well, some among the Edharians have been letting their creepy-crawly brains get the better of them,” Tulia said. “They don’t want to believe in the mead and the speelycaptor. Apparently, Orolo brokered a three-way deal that sent Arsibalt to the ROF in exchange for—”

“Stop,” I said, “I don’t want to hear it.”

“You know what Orolo did and so it’s easier for you to accept,” she said. “Others are having trouble with it—they want to make it into a political conspiracy and say that the thing with the mead never happened.”

“Not even I am that cynical about Suur Trestanas,” I said. In the corner of my eye I saw Tulia turn her head to look at me.

“Okay,” I admitted, “Let me put it differently. I don’t think she’s a conspiracist. I think she’s just plain evil.”

That seemed to satisfy Tulia.

“Look,” I said, “Fraa Orolo used to say that the concent was just like the outside world, except with fewer shiny objects. I had no idea what he was getting at. Now that he’s gone, I see it. Our knowledge doesn’t make us better or wiser. We can be just as nasty as those slines that beat up Lio and Arsibalt for the fun of it.”

“Did Orolo have an answer?”

“I think he did,” I said, “he was trying to explain it to me during Apert. Look for things that have beauty—it tells you that a ray is shining in from—well—”

“A true place? The Hylaean Theoric World?” Again her face was hard to read. She wanted to know whether I believed in all that stuff. And I wanted to know if

“Well,” she said, after giving it a few moments’ thought, “it’s better than spending your life swapping conspiracy theories.”

Anyway I now had an excuse to hang around at Shuf’s Dowment: I was trying to act as a peacemaker among the orders by accepting the ROF’s standing invitation.

After breakfast each morning I would attend a lecture, typically with Barb, and work with him on proofs and problems until Provener and the midday meal. After that I would go out to the back part of the meadow where Lio and I were getting ready for the weed war, and work, or pretend to, for a while. I kept an eye on the bay window of Shuf’s Dowment, up on the hill on the other side of the river. Arsibalt kept a stack of books on the windowsill next to his big chair. If someone else was there, he would turn these so that their spines were toward the window. I could see their dark brown bindings from the meadow. But if he found himself alone, he would turn them so that their white page-edges were visible. When I noticed this I would stop work, go to a niche-gallery, fetch my theorics notes, and carry them over the bridge and through the page-tree-coppice to Shuf’s Dowment, as if I were going there to study. A few minutes later I’d be down in the sub-cellar, sitting crosslegged on that tarp and working with the tablet. When I was finished I would come back up through the cellars. Before ascending the flagstone steps I would look for another signal: if someone else was in the building, Arsibalt would close the door at the top of the stairs, but if he were alone, he’d leave it ajar.

One of the many advantages that photomnemonic tablets held over ordinary phototypes was that they made their own light, so you could work with them in the dark. This tablet began and ended with daylight. If I ran it back to the very beginning, it became a featureless pool of white light with a faint bluish tinge: the unfocused light of sun and sky that had washed over the tablet after I had activated it on top of the Pinnacle during Fraa Paphlagon’s Voco. If I put the tablet into play mode I could then watch a brief funny-looking transition as it had been slid into Clesthyra’s Eye, and then, suddenly, an image, perfectly crisp and clear but geometrically distorted.

Most of the disk was a picture of the sky. The sun was a neat white circle, off-center. Around the tablet’s rim was a dark, uneven fringe, like a moldy rind on a wheel of cheese: the horizon, all of it, in every direction. In this fisheye geometry, “down” for us humans—i.e., toward the ground—was always outward toward the rim of the tablet. Up was always inward toward the center. If several people had stood in a circle around Clesthyra’s eye, their waists would have appeared around the circumference of the image and their heads would have projected inward like spokes of a wheel.

So much information was crammed into the tablet’s outer fringe that I had to use its pan and zoom functions to make sense of it. The bright sky-disk seemed to have a deep dark notch cut into it at one place. On closer examination, this was the pedestal of the zenith mirror, which stood right next to Clesthyra’s Eye. Like the north arrow on a map, this gave me a reference point that I could use to get my bearings and find other things. About halfway around the rim from it was a wider, shallower notch in the sky-disk, difficult to make sense of. But if I turned it about the right way and gave my eye a moment to get used to the distortion, I could understand it as a human figure, wrapped in a bolt that covered everything except one hand and forearm. These were reaching radially outward (which meant down) and became grotesquely oversized before being cropped by the edge of the tablet. This monstrosity was me reaching toward the base of the Eye, having just inserted the tablet and secured the dust cover. The first time I saw this I laughed out loud because it made my elbow look as big as the moon, and by zooming in on it I could see a mole and count the hairs and freckles. My attempt to hide my identity by hooding myself had been a joke! If Suur Trestanas had found this tablet she could have found the culprit by going around and examining everyone’s right elbow.

When I let the tablet play forward, I could see the notch-that-was-me melt into the dark horizon-rim as I departed. A few moments later, a dark mote streaked around the tablet in a long arc, close to the rim: the aerocraft that had taken Fraa Paphlagon away to the Panjandrums. By freezing this and zooming in I could see the aerocraft clearly, not quite so badly distorted because it was farther away: the rotors and the streams of exhaust from its engines frozen, the pilot’s face, mostly covered by a dark visor, caught in sunlight shining through the windscreen, his lips parted as if he were speaking into the microphone that curved alongside his cheek. When I ran the time point forward a few minutes I was able to see the aerocraft flying back in the other direction, this time with the face of Fraa Paphlagon framed in a side-window, gazing back at the concent as if he’d never seen it before.

Then, by sliding my finger up along the side of the tablet for a short distance, I was able to make the sun commit its arc across the sky-disk and sink into the horizon. The tablet went dark. Stars must be recorded on it, but my eyes couldn’t see them very well because they hadn’t adjusted to the dark yet. A few red comets flashed across it—the lights of aerocraft. Then the disk brightened again and the sun exploded from the edge and launched itself across the sky the next morning.

If I ran my finger all the way up the side of the tablet in one continuous motion, it flashed like a strobe light: seventy-eight flashes in all, one for each day that the tablet had lodged in Clesthyra’s Eye. Coming to the last few seconds and slowing down the playback, I was able to watch myself emerging from the top of the stairs and approaching the Eye to remove the tablet during Fraa Orolo’s Anathem. But I hated to see this part of it because of the way my face looked. I only checked it once, just to be sure that the tablet had continued recording all the way until the moment I’d retrieved it.

I erased the first and last few seconds of the recording, so that if the tablet were confiscated it would not contain any images of me. Then I began reviewing it in greater detail. Arsibalt had mentioned seeing the Ita in this thing. Sure enough, on the second day, a little after noon, a dark bulge reached in from the rim and blotted out most of the sky for a minute. I ran it back and played it at normal speed. It was one of the Ita. He approached from the top of the stairs carrying a squirt-bottle and a rag. He spent a minute cleaning the zenith mirror, then approached Clesthyra’s Eye—which was when his image really became huge—and sprayed cleaning fluid on it. I flinched as if the stuff were being sprayed into my face. He gave it a good polish. I could see all the way up into his nostrils and count the hairs; I could see the tiny veins in his eyeballs and the striations in his iris. So there was no doubt that this was Sammann, the Ita whom Jesry and I had stumbled upon in Cord’s machine-hall. In a moment he became much smaller as he backed away from the Eye. But he did not depart from the top of the Pinnacle immediately. He stood there for several moments, bobbed out of view, re-appeared, approached and loomed in Clesthyra’s Eye for a little bit, then finally went away.

I zoomed in and watched that last bit again. After he polished the lens, he looked down, as if he had dropped something. He stooped over, which made all but his backside disappear beyond the rim of the tablet. When he stood up, bulging back into the picture again, he had something new in his hand: a rectangular object about the size of a book. I didn’t have to zoom in on this to know what it was: the dust jacket that, a day previously, I had torn off this very tablet. The wind had snatched it from my hand, and in my haste to leave, I had, like an idiot, left it lying where it had fallen.

Sammann examined it for a minute, turning it this way and that. After a while he seemed to get an idea of what it was. His head snapped around to look at me—at Clesthyra’s Eye, rather. He approached and peered into the lens, then cocked his head, reached down, and (I guessed, though I couldn’t see) prodded the little door that covered the tablet-slot. His face registered something. If I’d wanted, I could have zoomed in on his eyeballs and seen what was reflected in them. But I didn’t need to because the look on his face told all.

Less than twenty-four hours after I had slipped that tablet into Clesthyra’s Eye, someone else in this concent had known about it.

Sammann stood there for another minute, pondering. Then he folded up the dust jacket, inserted it into a breast-pocket of his cloak, turned his back on me, and walked away.

I moved the tablet forward to a cloudy night, thereby plunging myself into almost total blackness, and I sat there in that hole in the ground and tried to get over this.

I was remembering the other evening, standing around the campfire, when I had criticized Orolo for being incautious, and told my friends that I’d be much more careful. What an idiot I was!

Watching Sammann pick up that dust jacket and put two and two together, my face had flushed and my heart had thumped as if I were actually there on top of the Pinnacle with him. But this was just a recording of something that had happened months ago. And nothing had come of it. Granted, Sammann could spill the beans any time he chose.

That was unnerving. But I could do nothing about it. Feeling embarrassed by a mistake I’d made months ago was a waste of time. Better to think about what I was going to do now. Sit here in the dark worrying? Or keep investigating the contents of this tablet? Put that way, it wasn’t a very difficult question. The fury that had taken up residence in my gut was a kind of anger that had to be acted upon. The action didn’t need to be sudden or dramatic. If I’d joined one of the other orders, I might have made acting upon it into a sort of career. Using it as fuel, I could have spent the next ten or twenty years working my way up the hierarch ranks, looking for ways to make life nasty for those who had wronged Orolo. But the fact of the matter was that I’d joined the Edharians and thereby made myself powerless as far as the internal politics of the concent were concerned. So I tended to think in terms of murdering Fraa Spelikon. Such was my anger that for a little while this actually made sense, and from time to time I’d find myself musing about how to carry it off. There were a lot of big knives in the kitchen.

So how fortunate it was that I had this tablet, and a place in which to view it. It gave me something to act on—something, that is, besides Fraa Spelikon’s throat. If I worked on it hard enough and were lucky, perhaps I could come up with some result that I could announce one evening in the Refectory to the humiliation of Spelikon, Trestanas, and Statho. Then I could storm out of the concent in disgust before they had time to Throw me Back.

And in the meantime, studying this thing answered that need in my gut to take some kind of action in response to what had been inflicted on Orolo. And I’d found that taking such action was the only way to transmute my anger back into grief. And when I was grieving—instead of angry—young fids no longer shied away from me, and my mind was no longer filled with images of blood pumping from Fraa Spelikon’s severed arteries.

So I had no choice but to put Sammann and the dust cover out of my mind, and concentrate instead on what Clesthyra’s Eye had seen during the night-time. I had kept track of the weather those seventy-seven nights. More than half had been cloudy. There had only been seventeen nights of really clear seeing.

Once I allowed my eyes to adjust to the darkness, it was easy to find north on this thing, because it was the pole around which all the stars revolved. If the image was frozen, or playing back at something like normal speed, the stars appeared as stationary points of light. But if I sped up the playback, each star, with the exception of the pole star, traced an arc centered on the pole as Arbre rotated beneath it. Our fancier telescopes had polar axis systems, driven by the clock, that eliminated this problem. These telescopes rotated “backwards” at the same speed as Arbre rotated “forwards” so that the stars remained stationary above them. Clesthyra’s Eye was not so equipped.

The tablet could be commanded to tell what it had seen in several different ways. To this point I’d been using it like a speelycaptor with its play, pause, and fast-forward buttons. But it could do things that speelycaptors couldn’t, such as integrate an image over a span of time. This was an echo of the Praxic Age when, instead of tablets like this one, cosmographers had used plates coated with chemicals sensitive to light. Because many of the things they looked at were so faint, they had often needed to expose those plates for hours at a time. A photomnemonic tablet worked both ways. If you were to “play back” such a record in speelycaptor mode, you might see nothing more than a few stars and a bit of haze, but if you configured the tablet to show the still image integrated over time, a spiral galaxy or nebula might pop out.

So my first experiment was to select a night that had been clear, and configure the tablet to integrate all the light that Clesthyra’s Eye had taken in that night into a single still image. The first results weren’t very good because I set the start time too early and the stop time too late, so everything was washed out by the brightness in the sky after dusk and before dawn. But after making some adjustments I was able to get the image I wanted.

It was a black disk etched with thousands of fine concentric arcs, each of which was the track made by a particular star or planet as Arbre spun beneath it. This image was crisscrossed by several red dotted lines and brilliant white streaks: the traces made by the lights of aerocraft passing across our sky. The ones in the center, made by high-flying craft, ran nearly straight. Over toward one edge the star-field was all but obliterated by a sheaf of fat white curves: craft coming in to land at the local aerodrome, all following more or less the same glide path.

Only one thing in this whole firmament did not move: the pole star. If our hypothesis was correct as to what Fraa Orolo had been looking for—namely, something in a polar orbit—then, assuming it was bright enough to be seen on this thing, it ought to register as a streak passing near the pole star. It would be straight or nearly so, and oriented at right angles to the myriad arcs made by the stars—it would move north-south as they moved east-west.

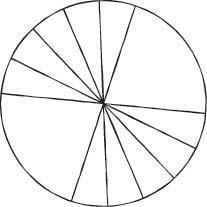

Not only that, but such a satellite should make more than one such streak on a given night. Jesry and I had worked it out. A satellite in a low orbit should make a complete pass around Arbre in about an hour and a half. If it made a streak on the tablet as it passed over the pole at, say, midnight, then at about one-thirty it should make another streak, and another at three, and another at four-thirty. It should always stay in the same plane with respect to the fixed stars. But during each of those ninety-minute intervals Arbre would rotate through twenty-two and a half degrees of longitude. And so the successive streaks that a given satellite made should not be drawn on top of each other. Instead they should be separated by angles of about twenty-two and a half degrees (or pi/8 as theoricians measured angles). They should look like cuts on a pie.

|

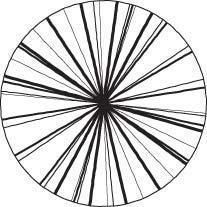

My work on that first day in the sub-cellar consisted of making the tablet produce a time exposure for the first clear night, then zooming in on the vicinity of the pole star and looking for something that resembled a pie-cutting diagram. I succeeded in this so easily that I was almost disappointed. Because there was more than one such satellite, what it looked like was more complex:

|

But if I looked at it long enough I could see it as several different pie-cut diagrams piled on top of each other.

“It’s an anticlimax,” I told Jesry at supper. We had somehow managed to avoid Barb and sit together in a corner of the Refectory.

“Again?”

“I’d sort of thought that if I could see anything at all in a polar orbit, that’d be the end of it. Mystery solved, case closed. But it is not so. There are several satellites in polar orbits. Probably have been ever since the Praxic Age. Old ones wear out and fall down. The Panjandrums launch new ones.”

“That is not a new result,” he pointed out. “If you go out at night and stand facing north and wait long enough, you can see those things hurtling over the pole with the naked eye.”

I chewed a bit of food as I struggled to master the urge to punch him in the nose. But this was how things were done in theorics. It wasn’t only the Lorites who said

“I don’t claim it is a new result,” I told him, with elaborate patience. “I’m only letting you know what happened the first time I was able to spend a couple of hours with the tablet. And I guess I am posing a question.”

“All right. What is the question?”

“Fraa Orolo must have known that there were several satellites in polar orbits and that this wasn’t a big deal. To a cosmographer, it’s no more remarkable than aerocraft flying overhead.”

“An annoyance. A distraction,” Jesry said, nodding.

“So what was it that he risked Anathem to see?”

“He didn’t just

I waved him off. “You know what I mean. This is no time to go Kefedokhles.”

Jesry gazed into space above my left shoulder. Most others would have been embarrassed or irritated by my remark. Not him! He couldn’t care less. How I envied him! “We know that he needed a speelycaptor to see it,” Jesry said. “The naked eye wasn’t good enough.”

“He had to see all of this in a different way. He couldn’t make time exposures on a tablet,” I put in.

“The best he could do, once the starhenge had been locked, was to stand out in that vineyard, freezing his arse off, looking at the pole star through the speelycaptor. Waiting for something to streak across.”

“When it showed up, it would zoom across the viewfinder in a few moments,” I said. We were completing each other’s sentences now. “But then what? What would he have learned?”

“The time,” Jesry said. “He would know what time it was.” He shifted his gaze to the tabletop, as if it were a speely of Orolo. “He makes a note of it. Ninety minutes later he looks again. He sees the same bird making its next pass over the pole.” Lio referred to satellites as birds—this was military slang he’d picked up from books—and the rest of us had adopted the term.

“That sounds about as interesting as watching the hour hand on a clock,” I said.

“Well, but remember, there’s more than one of these birds,” he said.

“I don’t

But Jesry was on the trail of an idea and had no time for me and my petty annoyance. “They can’t all be orbiting at the same altitude,” he said. “Some must be higher than others—those would have longer periods. Instead of ninety minutes they might take ninety-one or a hundred three minutes to go around. By timing their orbits, Fraa Orolo could, by making enough observations, compile sort of—”

“A census,” I said. “A list of all the birds that were up there.”

“Once he had that in hand, if there was any change—any anomaly—he’d be able to detect it. But until such time as he had completed that census, as you call it—”

“He’d be working in the dark, in more ways than one, wouldn’t he?” I said. “He’d see a bird pass over the pole but he wouldn’t know which bird it was, or if there was anything unusual about it.”

“So if that’s true we have to follow in his footsteps,” Jesry said. “Your first objective should be to compile such a census.”

“That is much easier for me than it was for Orolo,” I said. “Just looking at the tracks on the tablet you can see that some are more widely spread—bigger slices of the pie—than others. Those must be the high flyers.”

“Once you get used to looking at these images, you might be able to notice anomalies just by their general appearance,” Jesry speculated.

Which was easy for him to say, since he wasn’t the one doing it!

For the last little while he had seemed restless and bored. Now he broke eye contact, gazed around the Refectory as if seeking someone more interesting—but then turned his attention back to me. “New topic,” he announced.

“Affirmative. State name of topic,” I answered, but if he knew I was making fun of him, he didn’t show it.

“Fraa Paphlagon.”

“The Hundreder who was Evoked.”

“Yes.”

“Orolo’s mentor.”

“Yes. The Steelyard says that his Evocation, and the trouble Orolo got into, must be connected.”

“Seems reasonable,” I said. “I guess I’ve sort of been assuming that.”

“Normally we’d have no way of knowing what a Hundreder was working on—not until the next Centennial Apert, anyway. But before Paphlagon went into the Upper Labyrinth, twenty-two years ago, he wrote some treatises that got sent out into the world at the Decennial Apert of 3670. Ten years later, and again just a few months ago, our Library got its usual Decennial deliveries. So, I’ve been going through all that stuff looking for anything that references Paphlagon’s work.”

“Seems really indirect,” I pointed out. “We’ve got all of Paphlagon’s work right here, don’t we?”

“Yeah. But that’s not what I’m looking for,” Jesry said. “I’m more interested in knowing who, out there, was paying attention to Paphlagon. Who read his works of 3670, and thought he had an interesting mind? Because—”

“Because

“Exactly.”

“So what have you found?”

“Well, that’s the thing,” Jesry said. “Turns out Paphlagon had two careers, in a way.”

“What do you mean—like an avocation?”

“You could say his avocation was philosophy. Metatheorics. Procians might even call it a sort of religion. On the one hand, he’s a proper cosmographer, doing the same sort of stuff as Orolo. But in his spare time he’s thinking big ideas, and writing it down—and people on the outside noticed.”

“What kind of ideas?”

“I don’t want to go there now,” Jesry said.

“Well, damn it—”

He held up a hand to settle me. “Read it yourself! That’s not what I’m about. I’m about trying to reckon who picked him and why. There’s lots of cosmographers, right?”

“Sure.”

“So if he was Evoked to answer cosmography questions, you have to ask—”

“Why him in particular?”

“Yeah. But it’s rare to work on the metatheorical stuff he was interested in.”

“I see where you’re going,” I said. “The Steelyard tells us he must have been Evoked for

“Yeah,” Jesry said. “Anyway, not that many people paid attention to Paphlagon’s metatheorics, at least, judging from the stuff we got in the deliveries of 3680 and 3690. But there’s one suur at Baritoe, name of Aculoa, who really seems to admire him. Has written two books about Paphlagon’s work.”

“Tenner or—”

“No, that’s just it. She’s a Unarian. Thirty-four years straight.”

So she was a teacher. There was no other reason to spend more than a few years in a Unarian math.

“Latter Evenedrician,” Jesry said, answering my next question before I’d asked it.

“I don’t know much about that order.”

“Well, remember when Orolo told us that Saunt Evenedric worked on different stuff during the second half of his career?”

“Actually, I think Arsibalt’s the one who told us that, but—”

Jesry shrugged off my correction. “The Latter Evenedricians are interested in exactly that stuff.”

“All right,” I said, “so you reckon Suur Aculoa fingered Paphlagon?”

“No way. She’s a philosophy teacher, a One-off…”

“Yeah, but at one of the Big Three!”

“That’s my point,” Jesry said, a little testy, “a lot of important S#230;culars did a few years at Big Three maths when they were younger—before they went out and started their careers.”

“You think this suur had a fid, ten or fifteen years ago maybe, who’s gone on to become a Panjandrum. Aculoa taught the fid all about how great and wise Fraa Paphlagon was. And now, something’s happened—”

“Something,” Jesry said, nodding confidently, “that made that ex-fid say, ‘that tears it, we need Paphlagon here yesterday!’”

“But what could that something be?”

Jesry shrugged. “That’s the whole question, isn’t it?”

“Maybe we could get a clue by investigating Paphlagon’s writings.”

“That is obvious,” Jesry said. “But it’s rather difficult when Arsibalt’s using them as a semaphore.”

It took me a moment to make sense of this. “That stack of books in the window—”

Jesry nodded. “Arsibalt took everything Paphlagon ever wrote to Shuf’s Dowment.”

I laughed. “Well then, what about Suur Aculoa?”

“Tulia’s going through her works now,” Jesry said, “trying to figure out if she had any fids who amounted to anything.”

Working in a hole in the ground had made me ignorant of all these goings-on. But now that Jesry had let me know that my fraas and suurs were working so hard, I redoubled my efforts with the tablet. Stored on that thing I had all of seventeen clear nights. Once I got the knack, it took me about half an hour’s work to configure the tablet to give me the time exposure for a given night. Then, using a protractor, I would spend another half hour or so measuring the angles between streaks. As Jesry had predicted, some birds made slightly larger angles than others, reflecting their longer periods, but the angle for a given bird was always the same, every orbit, every night. So in a sense it only took a single night’s observations to make a rough draft of the census. But I went ahead and did it for all seventeen of the clear nights anyway, just to be thorough, and because frankly I had no idea what to do next. I could polish off one, sometimes two nights’ observations every time I got a chance to go down into that sub-cellar, but I didn’t get that chance every day.

By the time I finished, I had been at it for about three weeks. Buds were out on the page trees. Birds were flying north. Fraas and suurs were poking around in their tangles, arguing about whether it was time to plant. The barbarian weed-horde was marshaling on the riverbank and getting ready to invade the fertile Plains of Thrania. Arsibalt was two-thirds of the way through his pile of Paphlagon. The vernal equinox was only a few days away. Apert had begun on the morning of the autumnal equinox—half a year ago! I could not understand where the time had gone.

It had gone the same place as all the thousands of years before it. I had spent it working. It didn’t matter that my work was secret, illicit, and could have got me Thrown Back. The concent didn’t care about that. Certain persons would have cared a lot. But this was a place for the avout to spend their lives working on such projects. And now that I

Since Arsibalt, Jesry, and Tulia had their minds on other projects, I didn’t tell them about Sammann. That was a topic reserved for Lio when we were out in the meadow coaxing the starblossom to grow in the right direction. Or, since it was Lio, doing whatever else had most recently jumped into his mind.

We had reacted in different ways to the loss of Orolo. In my case, it was bloody revenge fantasies that I kept to myself. Lio, on the other hand, had become entranced by ever weirder varieties of vlor. Two weeks ago, he had tried to get me interested in rake vlor, which I guessed was inspired by the story of Diax casting out the Enthusiasts. I had declined on grounds of not wanting to get a blood infection—a weaponized rake could give you mass-produced puncture wounds. Last week he had developed a keen interest in shovel vlor, and we had spent a lot of time squatting on the riverbank sharpening spades with rocks.

When he led me down to the river again one day, I assumed it was for more of the same. But he kept looking back over his shoulder and leading me in deeper. I’d been on enough furtive expeditions as a fid to know that he was checking the sight-lines to the Warden Regulant’s windows. Old habits kicked in; I became silent, and moved from one shady place to another until we had reached a place where the bending river had cut away the bank to form an overhang, sheltered from view. Fortunately no one was there having a liaison just now. It would have been a bad place for it anyway: mucky ground, lots of bugs, high probability of being interrupted by avout messing around on the river in boats.

Lio turned to face me. I was almost worried that he was going to make a pass at me.

But no. This was Lio we were talking about.

“I’d like you to punch me in the face,” he said. As if he were asking me to scratch his back.

“Not that I haven’t always dreamed of it,” I said, “but why would

“Hand-to-hand combat has been a common element of military training down through the ages,” he proclaimed, as if I were a fid. “Long ago it was learned that recruits—no matter how much training they had received—tended to forget everything they knew the first time they got punched in the face.”

“The first time

“Yeah. In peaceful, affluent societies where brawling is frowned on, this is a common problem.”

“Not being punched in the face a lot is a

“It is,” Lio said, “if you join the military and find yourself in hand-to-hand combat with someone who is actually trying to kill you.”

“But Lio,” I said, “you

“Yes,” he said, “and I have been trying to learn from that experience.”

“So why do you want me to punch you in the face

“As a way to find out whether I

“Why me? Why not Jesry? He seems more the type.”

“That is the problem.”

“I see your point. Why not Arsibalt, then?”

“He wouldn’t do it for real—and then he’d complain that he’d hurt his hand.”

“What are you going to tell people if you show up for dinner with a busted face?”

“That I was battling evildoers.”

“Try again.”

“That I was practicing falls, and landed wrong.”

“What if I don’t want to mess up my hand?”

He smiled and produced a pair of heavy leather work gloves. “Stuff some rags under the knuckles,” he suggested, as I was pulling them on, “if you’re that worried about it.”

Grandsuurs Tamura and Ylma drifted by on a punt. We pretended to pull weeds until they were out of sight.

“Okay,” Lio said, “my objective is to perform a simple takedown on you—”

“Oh,

“Nothing we haven’t done a hundred times,” he said, as if I would find this reassuring. “That’s why we came here.” He stomped the damp sand of the riverbank. “Soft ground.”

“Why—?”

“If I put up my hands to defend my face, I won’t be able to complete my objective.”

“I get it.”

Suddenly he came at me and took me down. “You lose,” he proclaimed, getting up.

“Okay.” I sighed, and clambered to my feet. Immediately he wheeled around and took me down again. I threw a playful blow at his head, way too late. This time he took me down a lot harder. Every one of the small muscles in my head felt as if it had been strained. He planted a dirty hand on top of my face and shoved off while getting back to his feet. The message was clear.

The next time I tried for real, but I didn’t have my feet planted and wasn’t able to hit very hard. And he was coming in too low.

The time after that, I got my center of gravity low, planted my feet in the mud, made a bone connection from hip to fist, and drilled him right on the cheekbone. “Good!” he moaned, as he was climbing off me. “See if you can actually slow me down though—that’s the whole point, remember?”

I think we did it about ten more times. Since I was suffering a lot more abuse than he was, I sort of lost track. On my best go, I was able to throw him off stride for a moment—but he still took me down.

“How much longer are we going to do this?” I asked, lying in the mud, in the bottom of an Erasmas-shaped crater. If I refused to get up, he couldn’t take me down.

He scooped up a double handful of river water and splashed it on his face, rinsing away blood from nostrils and eyebrows. “That should do,” he said. “I’ve learned what I wanted.”

“Which is?” I asked, daring to sit up.

“That I’ve adjusted, since what happened at Apert.”

“We did all that to obtain a

“If you want to think of it that way,” he said, and scooped up more water.

I’d never get such a fine opportunity again, so I rolled up, put a foot in his backside, and sent him headlong into the river.

Later, as Lio was engrossed in the comparatively normal and sane activity of shovel-sharpening, I got us back on the topic of what I’d been seeing in the tablet: specifically, Sammann’s behavior during his noon visits.

Once I’d gotten over that sick feeling of having been found out, I’d begun to brood over some other questions. Was it merely a coincidence that the Ita who had discovered the dust jacket was the same one who had visited Cord in the machine hall? I reckoned that either it

“Has dis Ita tried to cobbudicade wid you?” Lio asked through puffy lips.

“You mean, like, sneaking into the math at night to slip me notes?”

Lio was baffled by my answer. He showed this in his usual way: by correcting his posture. The scrape of the rock on the shovel paused for a moment. Then he got it. “No, I don’t mean

“No, Thistlehead, I have to confess I haven’t the faintest idea—”

“If anyone understands surveillance, it’s those guys,” Lio pointed out. “If you buy into Saunt Patagar’s Assertion, sure.”

Lio seemed disappointed that I was so naive as not to believe this. He went back to work on that rock. The scraping really set my teeth on edge but I reckoned it must be putting the hurt on any spies who might be eavesdropping.

Apparently my new role at the Concent of Saunt Edhar was to be the sheltered innocent. I said, “Well, answer me this. If they have us under total surveillance, they must know everything about me and the tablet, right?”

“Well, yeah, you’d think so.”

“So why hasn’t anything happened?” I asked him. “It’s not like Spelikon and Trestanas have soft spots for me.”

“That doesn’t surprise me,” he insisted. “I don’t think there’s anything strange about that.”

“How do you figure?”

He paused long enough to give me the idea he was making up an answer on the spot. He dipped his sharpening-rock into the river. “The Ita can’t be telling the Warden Regulant everything they know. Trestanas would have to spend every minute of every day with them, to take in so much intelligence. The Ita must make decisions as to what they will pass on and what they will withhold.”

What Lio was saying opened up all sorts of interesting scenarios that would take me some time to sort out. I didn’t want to stand there with my mouth hanging open any longer than I already had, so I bent down and grabbed the handle of the shovel. It wasn’t going to get any sharper. I looked around for a stand of slashberry that needed to be massacred. It didn’t take long to find one. I made for it and Lio followed me.

“That’s giving the Ita a lot of responsibility,” I said, raising the shovel, then driving it down and forward into the roots of the slashberry canes. Several of them toppled. Most satisfying.

“Assume that they are as intelligent as we are,” Lio said. “Come on! They operate complicated syntactic devices for a living. They created the Reticulum. No one knows better than they do that knowledge is power. By employing strategy and tactics in what they say and what they don’t, they must be able to get things they want.”

I took down a square yard of slashberry while thinking about what he said.

“You’re saying there’s a whole world of Ita/hierarch politics going on over there that we know nothing about.”

“Has to be. Or else they wouldn’t be human,” Lio said.

Then he used Hypotrochian Transquaestiation on me: he changed the subject in such a way as to imply that the question had just been settled—that he had won the point and I had lost. “So, back to my question: does Sammann do anything else on the tablet that sends you a message—or at least indicates he knows that his image is being recorded?” He chucked his sharpening-rock into the river.

The correct response to Hypotrochian Transquaestiation was

After that I couldn’t get into the cellar for almost a week. The concent was getting ready for some equinox celebrations and so I had chant rehearsals. The weed war was entering a stage that demanded I draw at least one sketch of it. I had to get my tangle planted. When I was free, there always seemed to be other people at Shuf’s Dowment. The place was becoming hip!

“Be careful what you wish for,” Arsibalt moaned to me, one afternoon. I was helping him carry a stack of beehive frames into a wood shop. “I invited one and all to use the Dowment—now they are doing so—and I can’t work there!”

“Nor I,” I pointed out.

“And now this!” He picked up a putty knife, which I was pretty sure was the wrong tool for the job, and began to pick absent-mindedly at a patch of rotten wood on the corner of a frame. “Disaster!”

“Do you know anything about woodworking?” I asked.

“No,” he admitted.

“How about the metatheorical works of Fraa Paphlagon?”

“That I know a few things about,” he said. “And what is more, I think Orolo wanted us to learn about them.”

“How so?”

“Remember our last dialog with him?”

“Pink nerve-gas-farting dragons. Of course.”

“We must come up with a more dignified name for it before we commit it to ink,” Arsibalt said with a grimace. “Anyway, I believe that Orolo was pushing us to think about some of the ideas that were—

“Funny he didn’t mention Paphlagon, in that case,” I pointed out. “I remember talking about the later works of Saunt Evenedric, but—”

“One leads to the other. We would have found our way to Paphlagon in due course.”

“You would’ve, maybe,” I said. “What’s it all about?” This seemed a reasonable question. But Arsibalt flinched.

“The sort of stuff Procians hate us for.”

“Like, the Hylaean Theoric World?” I asked.

“That’s what they would call it, as a backhanded way of suggesting we are naive. But, starting at least as early as Protas, the idea of the HTW was developed into a more sophisticated metatheorics. So you could say that Paphlagon’s work is to classical Protan thought what modern group theory is to counting on one’s fingers.”

“But still related to it?”

“Certainly.”

“I’m just thinking back to my conversation with that Inquisitor.”

“Varax?”

“Yeah. I’m wondering whether his interest in the topic—”

“Correction: he was interested in

“Yeah, exactly—whether that might be further evidence for the existence of the Hypothetical Important Fid of Suur Aculoa.”

“I think we should be careful speculating about the HIFOSA until Suur Tulia has actually found evidence of his or her existence,” Arsibalt said. “Otherwise we’ll be coming up with all manner of speculations that would never make it past the Rake.”

“Well, without telling me everything you know about it,” I said, “can you give me a clue as to why anyone in the S#230;cular world would think Paphlagon’s work might be of practical importance?”

“Yes,” he said, “if you fix this beehive for me.”

“You know about atom smashers? Particle accelerators?”

“Sure,” I said. “Praxic Age installations. Huge and expensive. Used to test theories about elementary particles and forces.”

“Yes,” Arsibalt said. “If you can’t test it, it’s not theorics—it’s metatheorics. A branch of philosophy. So, if you want to think of it this way, our test equipment is what defines the boundary separating theorics from philosophy.”

“Wow,” I said, “I’ll bet a philosopher would really jump down your throat for talking that way. It’s like saying that philosophy is nothing more than bad theorics.”

“There are some theors who would say so,” Arsibalt admitted. “But those people aren’t really talking about philosophy

“What kind of stuff are you talking about?”

“Well, they speculate as to what the next theory might look like. They develop the theory and try to use it to make predictions that might be testable. In the late Praxic Age, that usually meant constructing an even bigger and more expensive particle accelerator.”

“And then came the Terrible Events,” I said.

“Yes, no more expensive toys for theors after that,” Arsibalt said. “But it’s not clear that it actually made that much of a difference. The biggest machines, in those days, were already pushing the limits of what could be constructed on Arbre with reasonable amounts of money.”

“I hadn’t known that,” I said. “I always tend to assume there’s an infinite amount of money out there.”

“There might as well be,” Arsibalt said, “but most of it gets spent on pornography, sugar water, and bombs. There is only so much that can be scraped together for particle accelerators.”

“So the Turn to Cosmography might have happened even without the Reconstitution.”

“It was already happening,” Arsibalt said, “as the theors of the very late Praxic Age were coming to terms with the fact that no machine would be constructed during their lifetimes that would be capable of testing the theorics to which they were devoting their careers.”

“So those theors had no alternative but to look to the cosmos for givens.”

“Yes,” Arsibalt said. “And in the meantime we have people like Fraa Paphlagon.”

“Meaning what? Both theors and philosophers?”

He thought about it. “I’m trying to respect your earlier request that I not simply bury you in Paphlagon,” he explained, when he caught me looking, “but this forces me to work harder.”

“Fair is fair,” I pointed out, brandishing a crosscut saw that I had been putting to use.

“You could think of Paphlagon—and presumably Orolo—as

“Theors,” I said, “who turned to philosophy when theorics stopped.”

“Slowed down,” Arsibalt corrected me, “waiting for results from places like Saunt Bunjo’s.”

Bunjo was a Millenarian math built around an empty salt mine two miles underground. Its fraas and suurs worked in shifts, sitting in total darkness waiting to see flashes of light from a vast array of crystalline particle detectors. Every thousand years they published their results. During the First Millennium they were pretty sure they had seen flashes on three separate occasions, but since then they had come up empty.

“So, in the meantime, they’ve been fooling around with ideas that people like Evenedric came up with when they reached the edge of theorics?”

“Yes,” Arsibalt said. “There was a profusion of them, right around the time of the Reconstitution, all variations on the theme of the polycosm.”

“The idea that our cosmos is not the only one.”

“Yes. And that’s what Paphlagon writes about when he isn’t studying

“Now I’m a little confused,” I said, “because I thought you told me just a minute ago that he was working on the HTW.”

“Well, but you could think of Protism—the belief that there is another realm of existence populated by pure theorical forms—as the earliest and simplest polycosmic theory,” he pointed out.

“Because it posits two cosmi,” I said, trying to keep up, “one for us, and one for isosceles triangles.”

“Yes.”

“But the polycosmic theories I’ve heard about—the circa-Reconstitution ones—are a whole different kettle of fish. In those theories, there are multiple cosmi separate from our own—but similar. Full of matter and energy and fields. Always changing. Not eternal triangles.”

“Not always as similar as you think,” Arsibalt said. “Paphlagon is part of a tradition that believed that classical Protism was just another polycosmic theory.”

“How could you possibly—”

“I can’t tell you without telling you everything,” Arsibalt said, holding up his fleshy hands. “The point I’m getting at is that he believes in some form of the Hylaean Theoric World.

“So if the HIFOSA really exists—” I said.

“He or she summoned Paphlagon because the polycosm somehow became a hot topic.”

“And we are guessing that whatever made it hot, also triggered the closure of the starhenge.”

Arsibalt shrugged.

“Well, what could that possibly be?”

He shrugged again. “That’s one for you and Jesry. But don’t forget that the Panjandrums might simply be confused.”

Finally one day I made it down into the sub-cellar of Shuf’s Dowment and spent three hours watching Sammann eat lunches. He made the trip almost every day, but not always at the same time. If the weather was fine and the time of day was right, he would sit on the parapet, spread out some food on a little cloth, and enjoy the view while he ate. Sometimes he read a book. I couldn’t identify all of his little morsels and delicacies, but they looked better than what we had for lunch. Sometimes, if the wind blew out of the northeast, we could smell the Ita cooking. It always seemed as if they were taunting us.

“Results!” I proclaimed to Lio the next time I was alone with him in the meadow. “Sort of.”

“Yeah?”

“You were right, I think.”

“Right about what?” For so much time had passed that he had forgotten our earlier talk about Sammann. I had to remind him. Then, he was taken aback. “Wow,” he said, “this is big.”

“Could be. I still don’t know what to make of it,” I said.

“What does he do? Hold up a sign in front of the Eye? Use sign language?”

“Sammann’s too clever for that,” I said.

“What? It sounds like you’re speaking of an old friend.”

“I almost feel that way about him by this point. He and I have had a lot of lunches together.”

“So, how does he—

“For the first sixty-eight days, he’s a real bore,” I said. “Then on Day Sixty-nine, something happens.”

“Day Sixty-nine? What does that mean to the rest of us?”

“Well, it’s about two weeks after the solstice and nine days before Orolo got Thrown Back.”

“Okay. So what does Sammann do on Day Sixty-nine?”

“Well, normally, when he gets to the top of the stair, he unslings a bag from his shoulder and hangs it around a stone knob that sticks up from the parapet there. He cleans the optics. Then he goes over and sits on the parapet—it has a flat top about a foot wide—and takes his lunch out of that bag and spreads it out there and eats it.”

“Okay. What happens on Day Sixty-nine?”

“In addition to the shoulder bag, he is carrying something cradled in one arm like a book. The first thing he does is set this down on the parapet. Then he goes about his usual routine.”

“So it’s sitting there in plain view of the Eye.”

“Exactly.”

“Can you zoom in on it?”

“Of course.”

“Can you read its title?”

“Turns out it’s not a book at all, Lio. It is another dust jacket—just like the one Sammann found up there the first day. Except this one is big and heavy because it contains—”

“Another tablet!” Lio exclaimed, then paused to consider it. “I wonder what that means.”

“Well, we have to assume he had just picked it up elsewhere in the starhenge.”

“He doesn’t leave it there, I assume.”

“No, when he’s finished eating he takes it with him.”

“I wonder why he’d choose that day of all days to snatch a tablet.”

“Well, I’m thinking it must have been around Day Sixty-nine that Fraa Spelikon’s investigation of Orolo really began to pick up steam. Now, you might remember that when I sneaked up there during the Anathem, on Day Seventy-eight, I checked the M amp; M—”

“And found it empty,” Lio said with a nod. “So. On Day Sixty-nine, Spelikon probably ordered Sammann to fetch the tablet that Orolo had left in the M amp; M. Which Sammann did. But Spelikon didn’t know about the one you’d put in Clesthyra’s Eye, so he didn’t ask for it.”

“But

“And had made up his mind not to tell Spelikon. But on Day Sixty-nine he didn’t try to hide the fact that he’d just grabbed Orolo’s tablet.” Lio shook his head. “I don’t get it. Why would he risk letting you know that?”

I threw up my hands. “Maybe it’s not such a risk for him. He’s already Ita. What can they do to him?”

“Good point. They can’t be nearly as afraid of the Warden Regulant as we are.”

I was a little bit irritated to be reminded that we were afraid, but, considering all of the skulking around I’d been doing lately, I couldn’t argue.

I’d been getting better, I realized. Recovering from the loss of Fraa Orolo. Forgetting how sad and angry I was. And when Lio mentioned the Warden Regulant, it reminded me.

Anyway, there was a long silence now as Lio assimilated all of this. We actually got some work done. On the weeds I mean.

“Well,” he finally said, “what happens after that?”

“Day Seventy, cloudy. Day Seventy-one, snowing. Day Seventy-two, snowing. Can’t see anything because the lens is covered. Day Seventy-three, it’s brilliant weather. Most of the snow has melted off by the time Sammann gets there. He cleans the place up and has lunch. He’s wearing goggles.”

“Like sunglasses?”

“Bigger and thicker.”

“Like what mountain climbers wear?”

“That’s what I thought at first,” I said. “Actually, I had to watch Day Seventy-three several times before I got it.”

“Got what?” Lio asked. “It was bright, there was snow, he wore dark goggles.”

“

“But why would Sammann suddenly start wearing such a getup to clean the lenses?”

“He doesn’t actually have them on while he’s cleaning. They’re dangling around his neck on a strap,” I said. “Then he puts them on and eats his lunch as usual. But the entire time that he’s eating, he’s staring directly into the sun.

“And he never did this before Day Sixty-nine?”

“Nope. Never.”

“So do you think that he learned something—?”

“Something from Fraa Orolo’s tablet, maybe?” I said. “Or something Spelikon told him? Or perhaps scuttlebutt from other Ita in other concents, talking, or whatever they do, over the Reticulum?”

“Why watch the sun? That is completely off the track of what you have been doing, isn’t it?”

“

“So, have you started looking at the sun too?”

“I don’t have goggles,” I reminded him, “but I do have twenty-odd clear sunny days recorded on that tablet. So starting tomorrow I can at least look at what the sun was doing three and four months ago.”

The next morning, after a theorics lecture, Jesry and Tulia and I went talking in the meadow. It was the first really fine spring day and everyone was out walking around, so it felt as though we could do this without being conspicuous.

“I think I found the IFOSA,” Tulia announced.

“You mean the HIFOSA,” Jesry corrected her.

“No,” I said, “if Tulia has found such a person, it is no longer Hypothetical.”

“I stand corrected,” Jesry said. “Who is the Important Fid?”

“Ignetha Foral,” Tulia said.

“The surname sounds vaguely familiar,” Jesry said.

“The family has been wealthy for a few hundred years, which makes them old and well-established by S#230;cular standards. They have a lot of ties to the mathic world—especially Baritoe.”

Saunt Baritoe was adjacent to landforms that made a huge and excellent harbor when the sea level was behaving itself, when it wasn’t buried in pack ice, and when the river that emptied into it had not dried up or been diverted. For about a third of the time since the Reconstitution, a large city had existed around Baritoe’s walls—not always the same city, of course—and so it had the reputation of being urban and worldly, with many ties to families such as, apparently, the Forals. The Procians were powerful there, and in their Unarian math they trained many young S#230;culars who later went into law, politics, and commerce.

“What are we allowed to know of her?” Jesry asked.

The question was aptly phrased. Once a year, at Annual Apert, our Unarians reviewed summaries of the S#230;cular news of the year just ended. Then, once every ten years, just before Decennial Apert, they reviewed the previous ten annual summaries and compiled a decennial summary, which became part of our library delivery. The only criterion for a news item to make it into a summary was that it still had to seem interesting. This filtered out essentially all of the news that made up the S#230;cular world’s daily papers and casts. Jesry was asking Tulia what Ignetha Foral had done that was interesting enough to have made it into the most recent Decennial summary.

“She had an important post in the government—she was one of the dozen or so highest-ranking people—and she took a stand against the Warden of Heaven, and he got rid of her.”

“Killed her?”

“No.”

“Threw her into a dungeon?”

“No, just fired her. I speculate that she has some other job now where she still has enough pull to Evoke someone like Paphlagon.”

“So, she was a fid of Suur Aculoa?”

“Ignetha Foral spent six years in the Unarian math at Baritoe and wrote a treatise comparing Paphlagon’s work to that of some other, er…”

“People like Paphlagon,” Jesry said impatiently.

“Yeah, of previous centuries.”

“Did you read it?”

“We didn’t get a copy. Maybe in another ten years. I already went into the Lower Labyrinth and shoved a request through the grille.”

Someone at Baritoe—presumably a Unarian fid—would have to copy Foral’s treatise by hand and send it to us. If a book were very popular, fids would do this without being asked, and copies would circulate to other maths.

“You’d think a rich family would have had copies machine-printed,” Jesry said.

“Too vulgar,” Tulia said. “But I know the title:

“Hmm. Makes me feel like a bug under the Procians’ magnifying glass,” I said.

“Baritoe

“So, she was interested in the polycosm,” Jesry said before this could flourish into a spat. “What could have happened that would be observable from the starhenge and that would make the polycosm relevant?” It was the sort of question Jesry would never ask unless he already knew the answer, which he now supplied: “Something’s gone wrong with the sun, I’ll bet.”

I was poised to scoff, but held back, reflecting that Sammann had, after all, been looking at the sun. “Something visible with the naked eye?”

“Sunspots. Solar flares. These can affect our weather and so on. And ever since the Praxic Age, the atmosphere doesn’t protect us from certain things.”

“Well, if that’s where the action is, why was Orolo looking at the North Pole?”

“The aurora,” Jesry said, as if he actually knew what he was talking about. “It responds to solar flares.”

“But we haven’t had a single decent aurora this whole time,” Tulia pointed out, with a catlike look of satisfaction on her face.

“That we could see with the naked eye,” Jesry returned. “This tablet of ours could be the perfect instrument for observing not only auroras but the disk of the sun itself.”

“I notice it’s ‘our’ tablet now that it’s got something good on it,” I pointed out.

“If Suur Trestanas finds it, it’ll go back to being ‘your’ tablet,” Tulia said. She and I laughed but Jesry was determined not to be amused.

“Seriously,” Tulia continued, “that hypothesis doesn’t explain why they Evoked Paphlagon. Any cosmographer can look at solar flares.”

“What’s the connection to the polycosm, you’re asking?” Jesry said.

“Exactly.”

“Maybe there

“Maybe she’s being persecuted as a heretic, and they yanked Paphlagon so that they could burn him too,” Jesry suggested. And we chatted about such ideas for a few minutes before discarding all of them in favor of the proposition that Paphlagon must have been chosen for some good reason.

“Well,” Jesry said, “the way that the theors of old found themselves talking about the polycosm in the first place was by thinking about stars: how they formed, and what went on inside them.”

“Formation of nuclei and so on,” Tulia said.

“And not only that but, when the stars die, how do those nuclei get blown out into space so that they can form planets and—”

“And us,” I said.

“Yeah,” Jesry said. “It leads to the question, why are all of those processes so fine-tuned to produce life? A sticky question. Deolaters would say, ‘Ah, see, God made the cosmos just for us.’ But the polycosmic answer is, ‘No, there must be lots of cosmi, some good for life, most not—we only see one cosmos in which we are capable of existing.’ And

“I think I see where you’re going now when you guess something’s gone wrong with the sun,” I said. “Maybe there are some new solar observations that contradict what we thought we knew about the theorics of what goes on in the cores of stars. And maybe this has ramifications that extend all the way to those polycosmic theories that Paphlagon’s interested in.”

“Or—more likely—Ignetha Foral mistakenly

“I think she’s pretty smart,” Tulia demurred, but Jesry didn’t hear her because a resolution was forming in his head. He turned toward me. “I want to go down there and view this with you,” he said. “Or without you, if you are busy.”

For about twelve different reasons I hated this idea, but I couldn’t say so without making it look like I was trying to be a pig and monopolize the tablet. “Fine,” I said.

“Are you sure that’s a good idea?” Tulia said—sounding as if she were pretty sure it wasn’t. But before this could develop into a proper fight, we all took notice of the approach of Suur Ala, who was heading straight for us across the meadow. “Uh-oh,” Jesry said.

Suur Ala was unusual-looking in a way I’d never been able to pin down; sometimes I found myself staring at her during lectures or at Provener trying to make sense of her face. She had a round head on a slender neck, lately accentuated by a short haircut she had gotten during Apert; since then, one of the other suurs had been maintaining this for her. She had huge eyes, a delicate sharp nose, and a wide mouth. She was small and bony where Tulia was generous. Anyway there was something about her physical form that matched her soul.

She didn’t waste time greeting us. “For the eight-hundredth time in the last three months, Fraa Erasmas is at the center of a heated conversation. Carefully out of earshot of others. Complete with significant glances at the sky and at Shuf’s Dowment,” she began. “Don’t bother trying to explain it away, I know you guys are up to something. Have been for weeks and weeks.”

We all stood there for a long moment. My heart was pounding. Ala was squared off against the three of us, scanning our faces with those searchlight eyes.

“All right,” Jesry said, “we won’t bother.” But that was all he said. There followed another long silence. I was expecting a look of fury to come over Ala’s face. For her to make a threat to bring down the Inquisition on us. Instead of which her face slowly collapsed. For a moment I thought she might show some other emotion—I couldn’t guess what. But she passed from there to a blank resolute look, turned her back on us, and began walking away. After she’d gone a few paces, Tulia went after her, leaving Jesry and me alone. “That was weird,” he observed.

I could hardly respond. The miserable feeling that had kept me awake in my cell on the night that Ala had joined the New Circle had come over me again.

“You think she’ll rat us out?” I asked him.

I tried to put it in an incredulous tone of voice, as in

“But she was careful to approach us when no one else was around,” I pointed out.

“Maybe in hopes of negotiating some kind of deal with us?”

“What do we have to offer in the way of a deal!?” I snorted.

Jesry thought about it and shrugged. “Our bodies?”

“Now you’re just being obnoxious. Why don’t you say ‘our affections’ if you’re going to make such jokes.”

“Because I don’t think I have any affection for Ala,” Jesry said, “and I don’t think she has any for me.”

“Come on, she’s not that bad.”

“How can you say that after the little performance she just put on?”

“Maybe she was trying to warn us that we’re being too obvious.”

“Well, she might have a point there,” Jesry admitted. “We should stop talking out in the open where the whole math can observe us.”

“You have a better idea?”

“Yeah. The sub-cellar of Shuf’s Dowment, next time Arsibalt sends us the signal.”

As it turned out, this was only about four hours later. It all worked fine—superficially. Arsibalt sent the signal. Jesry and I noticed it from different places and converged on Shuf’s Dowment. No one was there except for Arsibalt. Jesry and I went below and got to work.

But in every other way it was wrong from the start. Whenever I went to Shuf’s Dowment, I took a circuitous route through the back of the page-tree-coppice. I never went the same way twice. Jesry, on the other hand, just crossed the bridge and made a beeline for it. But I couldn’t say his way was any worse than mine, because that day I encountered no fewer than four different people, or groups of people, out strolling around to enjoy the weather. Within a stone’s throw of the Dowment I almost tripped over Suur Tary and Fraa Branch who were enjoying a private moment together, all wrapped up in each other’s bolts.

When I finally reached the building, it was with the intent of calling the thing off. But Jesry wasn’t about to walk away. He talked me into going down there as Arsibalt looked on, growingly horrified, eyes jumping from door to window to door. So down we went, and crammed ourselves into that tiny place where I had spent so many hours by myself. But it wasn’t the same with him there. I’d grown used to the geometric distortion wreaked by the lens; he hadn’t, and spent a lot of time zooming in on different things just to see what they looked like. It was no different from what I had done on my first few sessions with it, but it made me want to scream. He didn’t seem to understand that we did not have time for this. When he got really interested in something, he would talk much too loudly. Both of us had to go out and urinate; I had to teach him about the “all clear” signal involving the door.

It seemed like two or three hours went by before we actually got around to observing the sun. The tablet worked as well for this as it did for looking at distant stars. It could only generate so much light, and so the sun appeared, not as a blinding thermonuclear fireball, but as a crisp-edged disk—the brightest thing on the tablet, certainly, but not so bright you couldn’t look at it. If you zoomed in on it and turned down the brightness, you could observe sunspots. I couldn’t really say whether there was an exceptional number of these. Neither could Jesry. By blacking out the sun’s disk and observing the space around it, we could look for solar flares, but there was nothing unusual going on that we could see. Not that either of us was an expert on such things. We’d never paid much attention to the sun before, considering it an obnoxious, wayward star that interfered with our observations of all the other stars.

After we became discouraged, and convinced ourselves that the hypothesis about Sammann and the goggles was wrong, and that we’d wasted the whole afternoon, we attempted to leave, and found the door at the top of the stairs closed. Someone else was in the building; it wasn’t safe to go out.

We waited for half an hour. Maybe Arsibalt had closed the door in error. I crept up and put my ear to it. He was carrying on a conversation with someone there, and the longer I listened to their muffled voices the more certain I became that the other person was Suur Ala. She had tracked us here!

Jesry had uncomplimentary things to say about her when I came back down to report this news. Half an hour later she was still there. Both of us were starving. Arsibalt must be in a state of animalistic terror.

Clearly our secret was out, or soon to be out, to at least one person. Squatting there in the darkness, trapped like rats, we had more than enough time to think through the implications. To go on as if this had not happened would be senseless. So, having nothing else to do, we pulled the poly tarp up off the floor and wrapped the tablet in it. Then we maneuvered and squirmed into the remotest place we could find—the utmost frontier of Arsibalt’s explorations—and used his shovel to bury the tablet four feet deep. When we were finished with that project, and nicely covered with dirt, I went up and put my ear to the door again. This time I heard no conversation. But the door was still closed.

“I think Arsibalt has abandoned us in favor of supper,” I told Jesry. “But I’ll bet she’s still up there.”

“It’s not in her character to leave at this point,” Jesry said.

“Say, that’s the nicest thing you’ve ever said about her.”

“What do you think we should do, Raz?”

It was strange to hear Jesry asking for my views on any topic. I savored this novel experience for a few moments before saying, “If she intends to rat us out, I’m dead no matter what. But you have a chance. So, let’s go out together. You hood yourself and go straight out the back door and make yourself scarce. I’ll approach Ala and talk to her—she’ll be distracted long enough for you to melt into the darkness.”

“It’s a deal,” Jesry said. “Thanks, Raz. And remember: if it’s your body that she wants—”

“Shut up.”

“Okay, let’s do it,” Jesry said, pulling his bolt over his head. But I could see him shaking his head at the same time. “Can you believe this is what passes for excitement around this place?”

“Maybe someday your wish will be granted and something will happen in the world.”

“I thought this might be it,” he said, nodding toward the sub-cellar. “But, so far, there’s nothing but sunspots.”

The door opened and a light shone on us.

“Hello, boys,” said Suur Ala, “lose your way?”

Jesry was hooded; she couldn’t see his face. He bounded up the stairs, pushed his way past Ala, and headed for the back door. I was right behind him. I came face to face with Suur Ala just in time to hear a terrible thud from down the hall. Jesry was sprawled over the threshold, covered by a mess of bolt—from the waist up.

“No point hiding, Jesry. I’d know your smile anywhere,” Ala called.

Jesry got his legs under him, let his bolt drop back down over his arse, and ran off. Now that my eyes had adjusted to the light I could see that Ala had stretched her chord across the doorway at ankle level and tied it off between a couple of chairs flanking the exit. Lacking any other way to keep her bolt on, she had thrown it over herself loosely and was holding it up with one arm. She turned her back on me and shuffled over to retrieve the chord.

“Arsibalt left an hour ago,” she said. “I think he lost half his weight in perspiration.”

I couldn’t muster a lot of amusement, since I knew she was in a position to say equally funny things about me or Jesry if she wanted.

“Cat got your tongue?” she asked, after a good long while.

“How many other people know?”

“You mean, how many have I told? Or how many have figured it out on their own?”

“I guess…both.”

“I’ve told no one. As to the other question, I guess the answer would be, anyone who pays as much attention to you as I do, which probably means…no one.”

“Why would you pay attention to me?”

She rolled her eyes. “Good question!”

“Look, what do you want, Ala? What are you after?”

“It’s part of the rules of the game that I mustn’t tell you.”

“If this is about you trying to be some sort of junior Warden Regulant—her little protegee—then get it over with! Go and tell her. I’ll march out of the Day Gate at sunrise and go find Orolo.”

She was winding her chord about herself as I said this. Suddenly the bolt seemed to grow twice as large as all of the breath went out of her. Her chest collapsed and her head drooped. The big eyes closed for a few moments. Here was where any other girl would have gone to pieces.

It is hard to say just how monstrous I felt. I leaned back against the wall and let my head thud back as if attempting to escape from my own, hideously guilty skin. But there was no way out of it.

She had opened her eyes. They were gleaming, but they saw everything.

In a voice almost too quiet to hear, she said, “You need to take a bath.”

For once in my life I actually managed to see the double meaning. But Ala was already gone.

I’d have become a Deolater and gone on a pilgrimage of any length to find a magic bath that would wash away the mess I’d just made. The hardships of the journey would have been pleasant compared to my next week or so in the math. Not that Ala told anyone. She was too proud for that. But all the other suurs, beginning with Tulia, could tell she was suffering. And by breakfast the next morning, everyone had decided it must be my fault. I wondered how this worked. My first hypothesis was wrong on the face of it: that Ala had run home and narrated the story to a chalk hall full of appalled suurs. My second hypothesis was that she had been seen coming home miserable after having missed supper; I had been seen skulking home a little while later; ergo, I had done a bad thing to her. It wasn’t until later that I understood the much simpler truth: others had noticed that Ala had her eye on me, and so if Ala were miserable, it could only be because I had done something—it didn’t matter what—bad.

In a stroke I had been Thrown Back by every young female in the math. All the girls seemed to be aghast, all the time, because that was the look that would come over every girl’s face when she saw me.

The thing grew over time. If Ala had simply written up an account of what I’d done and stapled it to my chest, it wouldn’t have been so bad; but because the amount of information about what I had done was exactly zero, people’s imaginations went crazy. Young suurs cringed away from me. Older ones glared at me through supper. It doesn’t matter what you did, young man…we know you did

I did not see Ala again for four days, which was statistically improbable. It suggested that other suurs were acting as lookouts, tracking my movements so that they could tell Ala where not to be.

Arsibalt was so rattled that he could hardly speak until three days later, when he came to supper all dirty, and told me in a whisper that he had dug up the tablet from where Jesry and I had buried it (“ridiculously easy to find”) and hid it in a much better place (“safe and sound”).

Jesry and I knew better than to try to find any object that Arsibalt considered to be safe and sound. All we could do was wait for him to calm down.

I figured out why I never saw Ala: she and Tulia were spending an inordinate amount of time at the Mynster, doing some maintenance on the bells, practicing weird changes, and passing their knowledge down to the younger girls who would eventually replace them.