"Anathem" - читать интересную книгу автора (Stephenson Neal)

Part 6

PEREGRIN

We took turns going into the men’s and women’s toilet chambers to change. The shoes immediately drove me crazy. I kicked them off and parked them under a bench, then found a clear place on the narthex floor where I could spread out my bolt and fold it up. That involved stooping and squatting—tricky, in dungarees. I couldn’t believe people wore this stuff their whole lives!

Once I had my bolt reduced to a book-sized package, I wrapped my chord around it, put them into the department-store bag along with my balled-up sphere, and stuffed that into the bottom of the knapsack. Across the narthex, Lio was trying to perform some of his Vale-lore moves in his new clothes. He moved as if he’d just come down with a neurological disorder. Tulia’s clothes didn’t fit at all and she was negotiating a swap with one of the Centenarian suurs.

There had only been eight Convoxes. The first had coincided with the Reconstitution. After that, one had been held at each Millennium to compile the edition of the Dictionary that would be used for the next thousand years, and to take care of other business of concern to the Thousanders. There had been one for the Big Nugget and one at the end of each Sack.

Barb became jumpy, then unruly, and then wild. None of the hierarchs knew what to make of him.

“He doesn’t like change,” Tulia reminded me. The unspoken message: he’s your friend—he’s your problem.

Barb didn’t like being crowded either, so Lio and I crowded him. We crowded him into a corner where Arsibalt was encamped with his stack of books.

“Voco breaks the Discipline because the one Evoked goes forth alone, and from that point onward is immersed in the S#230;cular world,” Arsibalt intoned. “That’s why they can’t return. Convox is different. So many of us are taken at once that we can travel together and preserve the Discipline within our Peregrin group.”

“Peregrin begins and ends at a math,” Barb said, suddenly calm.

“Yes, Fraa Tavener.”

“When we get to Saunt Tredegarh’s—”

“We’ll celebrate the aut of Inbrase,” Arsibalt prompted him, “and—”

“And then we’ll be together with other avout in the Convox,” Barb guessed.

“And then—”

“And then when we’re done doing whatever it is they want us to do, we make Peregrin back to Saunt Edhar,” Barb went on.

“Yes, Fraa Tavener,” said Arsibalt. I could sense him fending off the temptation to add

Barb calmed down. It wouldn’t last. Once we left the Day Gate, we’d be contending with minor violations of the Discipline all the time. Barb would be certain to notice these and point them out. Why, oh why, had he been Evoked? He was just a brand-new fid! I was going to be babysitting him through the entire Convox.

As the small hours of the morning passed, though, and the lapis sphere that represented Arbre in the orrery ticked slowly around, I settled down a little bit and remembered that half of what I now knew about theorics was thanks to Barb. What would it say about me if I ditched him?

It was getting light outside. Half of the Evoked had already departed. The hierarchs were pairing Tenners with Hundreders because many of the latter would need help from the former in speaking Fluccish and coping with the S#230;culum in general. Lio was summoned and went out with a couple of Hundreders. Arsibalt and Tulia were told to get ready.

I couldn’t go out barefoot. My shoes were under a bench by the orrery. Fraa Jad had parked himself on that bench. Right above my shoes. His head was bent. His hands were folded in his lap. He must be doing some kind of profound Thousander meditation. If I disturbed him just so that I could fetch my shoes, he would turn me into a newt or something.

No one else wanted to disturb him either. Tulia, then Arsibalt, left with Hundreders in tow. There were only three Evoked left: Barb, Jad, and I. Jad was still in his bolt and chord.

Barb headed for Fraa Jad. I broke into a sprint, and caught up with him just as he arrived.

“Fraa Jad must change clothes,” Barb announced, stretching his first-year Orth until it cracked.

Fraa Jad looked up. Until now I had thought that his hands were folded together in his lap. Now I saw that he was holding a disposable razor, still encased in its colorful package. I had one just like it in my bag. It was a common brand. Fraa Jad was reading the label. The big characters were Kinagrams, which he would never have seen before, but the fine print was in the same alphabet that we used.

“What principle explains the powers imputed by this document to the Dynaglide lubri-strip?” he asked. “Is it permanent, or ablative?”

“Ablative,” I said.

“It is a violation of the Discipline for you to be reading that!” Barb complained.

“Shut up,” Fraa Jad said.

“I don’t mean in any way to be disrespectful,” I tried, after a somewhat awkward and lengthy pause, “but—”

“Is it time to leave?” Fraa Jad asked, and checked the orrery as if it were a wristwatch.

“Yes.”

Fraa Jad stood up and, in the same motion, stripped his bolt off over his head. Some of the hierarchs gasped and turned their backs. Nothing happened for a little while. I rummaged in his shopping bag and found a pair of drawers, which I handed to him.

“Do I need to explain this?” I asked, pointing out the fly.

Fraa Jad took the garment from me and discovered how the fly worked. “Topology is destiny,” he said, and put the drawers on. One leg at a time. It was hard to estimate his age. His skin was loose and mottled, but he balanced perfectly on one leg, then the other, as he put on the drawers.

The rest of getting Fraa Jad decent went by without notable incidents. I retrieved my shoes and tried once more to remember how to tie them. Barb seemed amazingly content to follow the command to shut up. I wondered why I had never tried this simple tactic with him before.

Stumbling and shuffling in our shoes, hitching our trousers up from time to time, we walked out the Day Gate. The plaza was empty. We crossed the causeway between the twin fountains and entered into the burgers’ town. An old market had stood there until I’d been about six years old, when the authorities had renamed it the Olde Market, destroyed it, and built a new market devoted to selling T-shirts and other objects with pictures of the old market. Meanwhile, the people who had operated the little stalls in the old market had gone elsewhere and set up a thing on the edge of town that was now called the New Market even though it was actually the old market. Some casinos had gone up around the Olde Market, hoping to cater to people who wanted to visit it or who had business of one kind or another linked to the concent. But no one wanted to visit an Olde Market that was surrounded by casinos, and frankly the concent wasn’t that much of an attraction, so the casinos were looking dirty and forlorn. Sometimes at night we could hear music playing from dance halls in their basements but they were awfully quiet at the moment.

“We can obtain breakfast in there,” Barb said.

“Casino restaurants are expensive,” I demurred.

“They have a breakfast buffet that you can go to for free. My father and I would eat there sometimes.”

This made me sad but I could not dispute the logic, so I followed Barb and Jad followed me. The casino was a labyrinth of corridors that all looked the same. They saved money by keeping the lights dim and not washing the carpets; the mildew made us sneeze. We ended up in a windowless room below ground. Fleshy men, smelling like soap, sat alone or in pairs at tables. There was nothing to read. A speely display was mounted to the wall, showing feeds of news, weather, and sports. It was the first moving picture praxis that Fraa Jad had ever seen, and it took him some getting used to. Barb and I let him stare at it while we got food from the buffet. We put our trays down on a table and then I returned to Fraa Jad who was watching highlights of a ball game. A man at a nearby table was trying to draw him into conversation about one of the teams. Fraa Jad’s T-shirt happened to be emblazoned with the logo of the same team and this had caused the man to jump to a whole set of wrong conclusions. I got between Fraa Jad’s face and the speely and managed to break his concentration, then led him over to the buffet. Thousanders didn’t eat much meat because there wasn’t room to raise livestock on their crag. He seemed eager to make up for lost time. I tried to steer him toward cereal products but he knew what he wanted.

While we were eating, a news feed came up on the speely showing a Mathic stone tower, seen from a distance, at night, lit from above by a grainy red glow. The scene was very much like what the Thousanders’ math had looked like last night. But the building on the feed was not one that I had ever seen.

“That is the Millenarians’ spire in the Concent of Saunt Rambalf,” Fraa Jad announced. “I have seen drawings of it.”

Saunt Rambalf’s was on another continent. We knew little of it because it had no orders in common with ours. I’d run across the name recently, but I could not remember exactly where—

“One of the three Inviolates,” Barb said.

“Is that what you call us?” Jad asked.

Barb was right. The Flying Wedge monument inside our Year Gate bore a plaque telling the story of the Third Sack and mentioning the three Thousander maths, in all the world, that had not been violated: Saunt Edhar, Saunt Rambalf, and—

“Saunt Tredegarh is the third,” Barb continued.

As if the speely were responding to his voice, we now saw an image of a math that seemed to have been carved into the face of a stone bluff. It too was illuminated from above by red light.

“That’s odd,” I said. “Why would the aliens shine the light on the Three Inviolates? That is ancient history.”

“They are telling us something,” said Fraa Jad.

“What are they telling us? That they’re really interested in the history of the Third Sack?”

“No,” said Fraa Jad, “they are probably telling us that they have figured out that Edhar, Rambalf, and Tredegarh are where the S#230;cular Power stored all of the nuclear waste.”

I was glad we were speaking Orth.

We walked to a fueling station on the main road out of town and I bought a cartabla. They had them in different sizes and styles. The one I bought was about the size of a book. Its corners and edges were decorated with thick knobby pads meant to look like the tires of off-road vehicles. That’s because this cartabla was meant for people who liked that kind of thing. It contained topographic maps. Ordinary cartablas had different decorations and they only showed roads and shopping centers.

When we got outside I turned it on. After a few seconds it flashed up an error message and then defaulted to a map of the whole continent. It didn’t indicate our position as it ought to have done.

“Hey,” I said to the attendant, back inside, “this thing’s busted.”

“No it’s not.”

“Yes it is. It can’t fix our position.”

“Oh, none of them can today. Believe me. Your cartabla works fine. Hey, it’s showing you the map, isn’t it?”

“Yeah, but…”

“He’s right,” said another customer, a driver who had just pulled into the station in a long-range drummon. “The satellites are on the blink. Mine can’t get a fix. No one’s can.” He chuckled. “You just picked the wrong morning to buy a new cartabla!”

“So, this started last night?”

“Yeah, ’bout three in the morning. Don’t worry. The Powers That Be depend on those things! Military. Can’t get by without ’em. They’ll get it all fixed in no time.”

“I wonder if it has anything to do with the red lights shining on the—on the clocks last night,” I said, just to see what they might say. “I saw it on the speely.”

“That’s one of their festivals—it’s a ritual or something they do,” said the attendant. “That’s what I heard.”

This was news to the other customer, and so I asked the attendant where he had heard it. He tapped a jeejah hanging on a lanyard around his neck. “Morning cast from my ark.”

The natural question would now have been:

“The aliens are jamming the nav satellites,” I announced.

“Or maybe they just shot them down!” said Barb.

“Let’s buy a sextant, then,” suggested Fraa Jad.

“Those have not been made in four thousand years,” I told him.

“Let’s build one then.”

“I have no idea of all the parts and whatnot that go into a sextant.”

He found this amusing. “Neither do I. I was assuming we would design it from first principles.”

“Yeah!” snorted Barb. “It’s just geometry, Raz!”

“In the present age, this continent is covered by a dense network of hard-surfaced roads replete with signs and other navigational aids,” I announced.

“Oh,” said Fraa Jad.

“Between that and this”—I waved the cartabla—“we can find our way to Saunt Tredegarh without having to design a sextant from first principles.”

Fraa Jad seemed a little put out by this. A minute later, though, we happened to pass an office supply store. I ran in and bought a protractor, then handed it to Fraa Jad to serve as the first component in his homemade sextant. He was deeply impressed. I realized that this was the first thing he’d seen extramuros that made sense to him. “Is that a Temple of Adrakhones?” he asked, gazing at the store.

“No,” I said, and turned my back on it and walked away. “It is praxic. They need primitive trigonometry to build things like wheelchair ramps and doorstops.”

“Nonetheless,” he said, falling behind me, and looking back longingly, “they must have some perception—”

“Fraa Jad,” I said, “they have no awareness of the Hylaean Theoric World.”

“Oh. Really?”

“Really. Anyone out here who begins to see into the HTW suppresses it, goes crazy, or ends up at Saunt Edhar.” I turned around and looked at him. “Where did you think Barb and I came from?”

Once we had gotten clear as to that, Barb and Jad were happy to follow me and discuss sextants as I led them on a wide arc around the west side of Saunt Edhar to the machine hall.

“You come and go at interesting times; I’ll give you that,” was how Cord greeted me.

We had interrupted her and her co-workers in the middle of some sort of convocation. Everyone was staring at us. One older man in particular. “Who’s that guy and why does he hate me?” I asked, staring back at him.

“That would be the boss,” Cord said. I noticed that her face was wet.

“Oh. Hmm. Sure. It didn’t occur to me that you’d have one of those.”

“Most people out here do, Raz,” she said. “When a boss gives you that look, it’s considered bad form to stare back the way you are doing.”

“Oh, is it some kind of social dominance gesture?”

“Yeah. Also, busting into a private meeting in someone’s place of employment is out of bounds.”

“Well, as long as I have your boss’s attention, maybe I should let him know that—”

“You called a big meeting here at midday?”

“Yeah.”

“Or, as he would think of it, you—a total stranger—invited a whole lot of other total strangers to gather on his property—an active industrial site with lots of dangerous equipment—without asking him first.”

“Well, this is really important, Cord. And it won’t last long. Is that why you and your co-workers were having a meeting?”

“That was the first agenda item.”

“Do you think he is going to physically assault me? Because I know a little vlor. Not as much as Lio but—”

“That would be an unusual way to handle it. Out here it would be a legal dispute. But you guys have your own separate law, so he can’t touch you. And it sounds like the Powers That Be are leaning on him to let this thing happen. He’ll negotiate with them for compensation. He’s also negotiating with the insurance company to make sure that none of this voids his policy.”

“Wow. Things are complicated out here.”

Cord looked in the direction of the Pr#230;sidium and sniffled. “And they’re not…in there?”

I thought about that for a while. “I guess my disappearance on Tenth Night probably looks as weird to you as your boss’s insurance policy looks to me.”

“Correct.”

“Well, it wasn’t personal. And it hurt me a lot. Maybe as much as this mess hurts you.”

“That is unlikely,” Cord said, “since ten seconds before you walked in here I got fired.”

“That is wildly irrational behavior!” I protested. “Even by extramuros standards.”

“Yes and no. Yes, it’s crazy for me to get fired because of a decision you made without my knowledge. But no, in a way it’s not, because I’m weird here. I’m a girl. I use the machines to make jewelry. I make parts for the Ita and get paid in jars of honey.”

“Well, I’m really sorry—”

“Just stop,” she suggested.

“If there’s anything I can do—if you’d like to join the math—”

“The math you just got thrown out of?”

“I’m just saying, if there’s anything I can do to make it up to you—”

“Give me an adventure.”

In the moment that followed, Cord realized that this sounded weird, and lost her nerve. She held up her hands. “I’m not talking about some massive adventure. Just something that would make getting fired seem small. Something that I might remember when I’m old.”

Now for the first time I reviewed everything that had happened in the last twelve hours. It made me a little dizzy.

“Raz?” she said, after a while.

“I can’t predict the future,” I said, “but based on what little I know so far, I’m afraid it has to be a massive adventure or nothing.”

“Great!”

“Probably the kind of adventure that ends in a mass burial.”

That quieted her down a little bit. But after a while, she said: “Do you need transportation? Tools? Stuff?”

“Our opponent is an alien starship packed with atomic bombs,” I said. “We have a protractor.”

“Okay, I’ll go home and see if I can scrounge up a ruler and a piece of string.”

“That’d be great.”

“See you here at noon. If they’ll let me back in, that is.”

“I’ll see to it that they do. Hey, Cord—”

“Yeah?”

“This is probably the wrong time to ask…but could you do me one favor?”

I went into the shade of the great roof over the canal and sat on a stack of wooden pallets, then took out the cartabla and figured out how to use its interface. This took longer than I’d expected because it wasn’t made for literate people. I couldn’t make any headway at all with its search functions, because of all its cack-handed efforts to assist me.

“Where the heck is Bly’s Butte?” I asked Arsibalt when he showed up. It was half an hour before midday. About half of the Evoked had arrived. A small fleet of fetches and mobes had begun to form up: stolen, borrowed, or donated, I had no idea.

“I anticipated this,” Arsibalt said.

“Bly’s relics are all at Saunt Edhar,” I reminded him.

“Excellent! What did you steal?”

“A rendering of the butte as it appeared thirteen hundred years ago.”

“And some of his cosmographical notes?” I pleaded.

No such luck: Arsibalt’s face was all curiosity. “Why would you want Saunt Bly’s cosmographical notes?”

“Because he ought to have noted the longitude and latitude of the place from which he was making the observations.”

Then I remembered we had no way to determine our longitude and latitude anyway. But perhaps that information was entombed in the cartabla’s user interface.

“Well, perhaps it’s all for the best,” Arsibalt sighed.

“We are supposed to go

“I don’t think it’s that far out of the way.”

“Didn’t you just tell me you don’t know where it is?”

“I have a rough idea.”

“You can’t even be certain that Orolo

“Arsibalt, I don’t understand you. Why did you bother stealing Bly’s relics if you had no intention of going to find Orolo?”

“At the time I stole them,” he pointed out, “I didn’t know it was a Convox.”

It took me a moment to follow the logic. “You didn’t know we’d be coming back.”

“Correct.”

“You reckoned, after we got finished doing whatever it is they wanted us to do—”

“We could find Orolo, and live as Ferals.”

That was all interesting. Sort of poignant too. It did nothing, however, to solve the problem at hand.

“Arsibalt, have you noticed any pattern in the lives of the Saunts?”

“Quite a few. Which pattern would you like to draw to my attention?”

“A lot of them get Thrown Back before everyone figures out that they are Saunts.”

“Supposing you’re right,” Arsibalt said, “Orolo’s canonization is not going to happen for a long time; he’s not a Saunt yet.”

“Beg pardon,” said a man who had lately been hovering nearby with his hands in his pockets, “are you the leader?”

He was looking at me. I naturally glanced around to see what fresh trouble Barb and Jad had gotten into. Barb was standing not far away, watching some birds that had built their nests up in the steel beams that supported the roof. He’d been doing this for a solid hour. Jad was squatting in a dusty patch, drawing diagrams using a broken tap as a stylus. Shortly after we’d arrived, Fraa Jad had wandered into the machine hall and figured out how to turn on a lathe. Cord’s ex-boss almost

I guessed that by

“Yes,” I said, “I am called Fraa Erasmas.”

“Oh, good to meet you. Ferman Beller,” he said, and extended his hand a little uncertainly—he wasn’t sure if we used that greeting. I shook his hand firmly and he relaxed. He was a stocky man in his fifth decade. “Nice cartabla you got there.”

This seemed like an incredibly strange thing for him to say until I remembered that extras were allowed to have more than three possessions and that these often served as starting-points for small talk.

“Thanks,” I tried. “Too bad it doesn’t work.”

He chuckled. “Don’t worry. We’ll get you there!” I guessed he was one of the locals who had volunteered to drive us. “Say, look, there’s a guy over there wants to talk to you. Didn’t know if we should, you know, let him approach.”

I looked over and saw a man with a black stovepipe on his head, standing in the sun, glaring at me.

“Please send Sammann over,” I said.

“You can’t be serious!” Arsibalt hissed when Ferman was out of range.

“I sent for him.”

“How would you go about sending for an Ita?”

“I asked Cord to do it for me.”

“Is she here?” he asked, in a new tone of voice.

“I’m expecting her

The bells of Provener flipped switches in my brain, as if I were one of those poor dogs that Saunts of old would wire up for psychological experiments. First I felt guilty: late again! Then my legs and arms ached for the labor of winding the clock. Next would be hunger for the midday meal. Finally, I felt wounded that they’d managed to wind the clock without us.

“We’re going to hold much of the discussion in Orth because many of us don’t really speak Fluccish,” I announced, from my pallet-stack podium, to the whole group: seventeen avout, one Ita, and a roster of extramuros people that grew and shrank according to their attention span and jeejah usage but averaged about a dozen. “Suur Tulia will translate some of what we say, but a lot of our conversation is going to be about stuff that is of interest only to avout. So you might want to have your own conversation about logistics—such as lunch.” I saw Arsibalt nodding.

Then I switched to Orth. I was a little slow to get going because I was waiting for someone to point out that I was not actually the leader. But I had called this meeting, and I was standing on the stack of pallets.

And I was a Tenner. Our leader would have to be a Tenner who would be able to speak Fluccish and deal with the extramuros world. Not that I was an expert on that. But a Hundreder would be even more inept. Fraa Jad and the Hundreders couldn’t very well choose which Tenner was going to be the leader, because they’d never met any of us until a few hours ago. For years, however, all of them had watched me and my team wind the clock, which gave me, Lio, and Arsibalt the advantage that our faces were familiar. Jesry, the natural leader, was gone. I had won Arsibalt’s loyalty by speaking of lunch. Lio was too goofy and weird. So through no rational process whatsoever I was the leader. And I had no idea what I was going to say.

“We have to divide up among several vehicles,” I said, stalling for time. “For now we’ll stick with the same mixed groups of Tenners and Hundreders that were assigned in the Narthex this morning. We’ll do that because it’s simple,” I added, because I could see Fraa Wyburt—a Tenner, older than me—getting ready to lodge an objection. “Swap things around later if you want. But each Tenner is responsible for making sure his Hundreders don’t end up stranded in a vehicle with non-Orth speakers. I think we can all happily accept that responsibility,” I said, looking Fraa Wyburt in the eye. He looked ready to plane me but decided to back down for reasons I could only guess at. “How will those groups be distributed among vehicles? My sib, Cord, the young woman in the vest with the tools, has offered to take some of us in her fetch. That’s a Fluccish word. It is that industrial-looking vehicle that seems like a box on wheels. She wants me and her liaison-partner Rosk—the big man with the long hair—in there with her. Fraa Jad and Fraa Barb are with me. I have invited Sammann of the Ita to join us. I know some of you will object”—they were already objecting—“but that’s why I’m putting him in the fetch with me.”

“It’s disrespectful to put an Ita in with a Thousander!” said Suur Rethlett—another Tenner.

“Fraa Jad,” I said, “I apologize that we are discussing you as if you were not present. It goes without saying that you may choose whichever vehicle you want.”

“We are supposed to maintain the Discipline during Peregrin!” Barb helpfully reminded us.

“Hey, you guys are scaring the extras,” I joked. Because looking over the heads of my fraas and suurs I could see the extramuros people looking unnerved by our arguing. Tulia translated my last remark. The extras laughed. None of the avout did. But they did settle down a little.

“Fraa Erasmas, if I may?” said Arsibalt. I nodded. Arsibalt faced Barb but spoke loudly enough for all to hear: “We have been given two mutually contradictory instructions. One, the ancient standing order to preserve the Discipline during Peregrin. Two, a fresh order to get to Saunt Tredegarh by any means necessary. They have not provided us with a sealed train-coach or any other such vehicle that might serve as a mobile cloister. It is to be small private vehicles or nothing. And we don’t know how to drive. I put it to you that the new order takes precedence over the old and that we must travel in the company of extras. And to travel with an Ita is certainly no worse than that. I say it is better, in that the Ita understand the Discipline as well as we do.”

“Sammann’s in Cord’s fetch with me,” I concluded, before Barb could let fly any of the objections that had been filling his quiver during Arsibalt’s statement. “Fraa Jad’s wherever he wants to be.”

“I’ll travel in the way you have suggested, and make a change if it is not satisfactory,” said Fraa Jad. This silenced the remainder of the seventeen for a moment, simply because it was the first time most of them had heard his voice.

“That might happen immediately,” I told him, “because the first destination of Cord’s fetch will be Bly’s Butte where I will try to find Orolo.”

Now the extras really did have something to worry about, for the avout became quite loud and angry and my short tenure as self-appointed leader looked to be at an end. But before they pulled me down and Anathematized me I nodded to Sammann, who strode forward. I reached down and grabbed his hand and pulled him up to stand alongside me. The novel sight of a fraa touching an Ita broke the others’ concentration for a moment. Then Sammann began to speak, which was so arresting that after the first few words he had a silent, almost rapt audience. A couple of Centenarian suurs plugged their ears and closed their eyes in silent protest; three others turned their backs on him.

“Fraa Spelikon told me to go to the Telescope of Saunts Mithra and Mylax and retrieve a photomnemonic tablet that Fraa Orolo had placed there hours before the starhenge was closed by the Warden Regulant,” Sammann announced in correct but strangely accented Orth. “I obeyed. He did not issue any command as to information security relating to this tablet. So, before I gave it to him, I made a copy.” And with that Sammann withdrew a photomnemonic tablet from a bag slung over his shoulder. “It contains a single image that Fraa Orolo created, but never got to see. I summon the image now,” he said, manipulating its controls. “Fraa Erasmas, here, saw it a few minutes ago. The rest of you may view it if you wish.” He handed it down to the nearest avout. Others clustered around, though some still refused even to acknowledge that Sammann was present.

“We need to be discreet and not show this to the extras,” I said, “because I don’t think they have any idea what we are up against.”

But no one heard me because by then they were all looking at the image on the tablet.

What the tablet showed did not force anyone to agree with me, but it was a huge distraction from the argument we’d been having. Those who were inclined to see things my way derived new confidence from it. The rest of them lost their nerve.

It took an hour to figure out who was going in which vehicle. I couldn’t believe it could be so complicated. People kept changing their minds. Alliances formed, frayed, and dissolved. Inter-alliance coalitions snapped in and out of existence like virtual particles. Cord’s big boxy fetch, which had three rows of seats, was to be occupied by her, Rosk, me, Barb, Jad, and Sammann. Ferman Beller had a large mobe that was made to travel on uneven surfaces. He would take Lio, Arsibalt, and three of the Hundreders who had decided to throw in with us. We thought we had pretty efficiently filled the two largest vehicles, but at the last minute another extra who had been making a lot of calls on his jeejah announced that he and his fetch were joining our caravan. The man’s name was Ganelial Crade and he was pretty clearly some kind of Deolater from a counter-Bazian ark—whether Warden of Heaven or not, we didn’t know yet. His vehicle was an open-back fetch whose bed was almost completely occupied by a motorized tricycle with fat, knobby tires. Only three people could fit into its cab. No one wanted to ride with Ganelial Crade. I was embarrassed on his behalf, though not so embarrassed that I was willing to climb into his vehicle. At the last minute, some younger associate of his stepped up, tossed a duffel bag into the back, and climbed into the cab with him. So that completed the Bly’s Butte contingent.

The direct-to-Tredegarh contingent comprised four mobes, each with one owner/driver and one Tenner: Tulia, Wyburt, Rethlett, and Ostabon. Other seats in these vehicles were taken up by Hundreders who wanted no part of an Orolo expedition or by other extras who had volunteered to come on the journey.

With the exception of Cord and Rosk, all of the extras appeared to be part of religious groups, which made all of the avout more or less uncomfortable. I reckoned that if there had been a military base in this area the S#230;cular Power might have ordered some soldiers to dress up as civilians and drive us around, but since there wasn’t, they’d hit on the idea of relying on organizations that people were willing to volunteer for on short notice, which in this time and place meant arks. When I explained it to people in those terms, it seemed to settle them down a little bit. The Tenners sort of understood it. The Hundreders found it quite difficult to fathom and kept wanting to know more about the deologies espoused by their would-be drivers, which in no way shortened the process of getting them into vehicles.

Ganelial Crade was probably in his fourth decade, but you could mistake him for a younger man because he was slender and whiskerless. He announced that he knew the location of Bly’s Butte and that he would lead us there and we should follow him. Then he got into his fetch and started the engine. Ferman Beller ambled over and grinned at him until he opened his window, then started talking to him. Pretty soon I could tell that they were disagreeing about something—mostly by watching Crade’s passenger, who was glaring at Beller.

I got that mud-on-the-head sense of embarrassment again. Ganelial Crade had spoken with such confidence that I’d assumed he’d already gone over this plan with Ferman Beller and that the two of them had agreed on it. Now it was obvious that no such thing had ever happened. I’d been prepared to follow Crade wherever he led us.

I could now see that this business of being the leader was going to be a pain in the neck because people would always be trying to get me to do the wrong things or get rid of me altogether.

“Some leader!” I said, referring to myself.

“Huh?” asked Lio.

“Don’t let me do stupid things any more,” I ordered Lio, who looked baffled. I started walking towards Crade’s fetch. Lio and Arsibalt followed at a distance. Crade and Beller were openly arguing now. I really wanted no part of this but I had been cornered into doing something.

The problem, I realized, was that Crade claimed to have knowledge we didn’t have as to the location of Bly’s Butte. That was my fault. I’d made the error of admitting that I didn’t know exactly where it was. Inside the concent it was fine to admit ignorance, because that was the first step on the road to truth. Out here, it just gave people like Crade an opening to seize power.

“Excuse me!” I called out. Beller and Crade stopped arguing and looked at me. “One of my brothers has brought with him ancient documents from the concent that tell us where to go. By combining this knowledge with the skills of our Ita and the topographic maps on the cartabla, we can find our own way to the place we are going.”

“I know exactly where your friend went,” Crade began.

“We don’t,” I said, “but as I mentioned we can figure it out long before we get there.”

“Just follow me and—”

“That is a brittle plan. If we lose you in traffic we will be in a bad way.”

“If you lose me in traffic you can call me on my jeejah.”

This hurt because Crade was being more rational than I was, but I couldn’t back down at this point. “Mr. Crade, you may go on ahead if you like, and have the satisfaction of beating us there, but if you look in your rearview and notice that we are no longer visible, it is because we have decided to keep our own counsel as to how we should get there.”

Crade and his passenger now hated me forever but at least this was over.

This plan, however, necessitated a shake-up that put me and Sammann in Ferman Beller’s vehicle with Arsibalt. The three of us would navigate. Lio and a Hundreder moved to Cord’s fetch to balance the load; they would follow. Ganelial Crade sprayed us with loose rocks as he gunned his fetch out into the open.

“That man behaves so much like the villain in a work of literature, it’s almost funny,” Arsibalt observed.

“Yes,” said one of the Hundreders, “it’s as if he’d never heard of foreshadowing.”

“He probably

“Go ahead,” said the Hundreder, “and I’ll see if I can parse it.”

Fraa Carmolathu, as this Hundreder was called, was a little bit of a dork, but he had volunteered to go fetch Orolo, so he couldn’t be all bad. He was five or ten years older than Orolo, and I speculated that he was a friend of Paphlagon.

“How many roads lead northeast, parallel to the mountains?” I asked Beller. I was hoping he’d say

“Several,” he said. “Which one do you want to take, boss?”

“By definition a butte is free-standing—not part of a range,” Arsibalt said in Orth, “so—”

“It rises from the plateau south of the mountains,” I announced in Fluccish. “We don’t need to take a mountain road.”

Beller put the vehicle into gear and pulled out. I waved goodbye to Tulia. She was watching us go, looking a little shocked. Our departure

Before leaving town we stopped, or rather slowed down, at a place where we could get food without spending a lot of time. I remembered this kind of restaurant from my childhood but it was new to the Hundreders. I couldn’t help seeing it as they did: the ambiguous conversation with the unseen serving-wench, the bags of hot-grease-scented food hurtling in through the window, condiments in packets, attempting to eat while lurching down a highway, volumes of messy litter that seemed to fill all the empty space in the mobe, a smell that outstayed its welcome.

By the time we’d finished eating, we’d passed out of view of the Pr#230;sidium. We had left most of the slines’ quarter behind us and were moving across a sort of tidal zone that was part of the city when the city was big and part of the country when it wasn’t. Where a tidal zone would have driftwood, dead fish, and uprooted seaweed, this had stands of scrawny trees, animals killed by vehicles, and tousled jumpweed. Where the tidal zone would be littered with empty bottles and wrecked boats, this had empty bottles and abandoned fetches. The only thing of consequence was a complex where fuel trees that had been barged down from the mountains were chewed up and processed. There we were caught for a few minutes in a traffic jam of tanker-drummons. But few of these were going our way, and soon we had got clear of them and passed into the district of vegetable gardens and orchards that stretched beyond.

In my vehicle, besides me and Ferman Beller, were Arsibalt, Sammann, and two Hundreder Fraas, Carmolathu and Harbret. The other vehicle contained Cord, Rosk, Lio, Barb, Jad, and another Edharian from the Hundreder math: Fraa Criscan. I noted a statistical oddity, which was that there was only one female, and that was my sib, who was pretty unconventional as females went. Intramuros, we didn’t often see the numbers get so skewed. Extramuros, of course, it depended on what religions and social mores prevailed at a given time. Naturally, I wondered how this had come about, and spent a little while reviewing my memories of the hour-long scramble to get people into vehicles. Of course, the biggest factor in determining who’d go in which group was how one thought about Orolo and the mission to go and find him. Perhaps there was something about this foray that smelled good to men and bad to women.

We numbered twelve, not counting Ganelial Crade. This was a common size for an athletic team or a small military unit. It had been speculated for a long time that this was a natural size for a hunting party of the Stone Age, and that men were predisposed to feel comfortable in a group of about that size. Anyway, whether it was a statistical anomaly or primitive behavior programmed into our sequences, this was what we’d ended up with. I spent a few minutes wondering whether Tulia and some of the other suurs in the straight-to-Tredegarh contingent hated me for letting it come out this way, then forgot about it, since we needed to think about navigation.

From the drawing that Arsibalt had supplied—which showed the profile of a range of mountains in the distance—and from certain clues in the story of Saunt Bly as recorded in the Chronicles, and from things that Sammann looked up on a kind of super-jeejah, we were able to identify three different isolated mountains on the cartabla, any one of which might have been Bly’s Butte. They formed a triangle about twenty miles on a side, a couple of hundred miles from where we were now. It didn’t seem that far away but when we showed it to Ferman he told us we shouldn’t expect to reach it until tomorrow; the roads in that area, he explained, were “new gravel,” and it would be slow going. We could get there today, but it would be dark and we wouldn’t be able to do anything. Better to find a place to stay nearby and get an early start tomorrow.

I didn’t understand “new gravel” until several hours later when we turned off the main highway and on to a road that had once been paved. It almost would have been faster to drive directly over the earth than to pick our way over this crazed puzzle of jagged slabs.

Arsibalt was uncomfortable being around Sammann, which I could tell because he was extremely polite when addressing him. Complaining of motion sickness, he moved up to the seat next to Ferman and talked to him in Fluccish. I sat behind him and tried to catch up on sleep. From time to time my eyelids would part as we caught air over a gap in the road and I’d get a dreamy glimpse of some religious fetish swinging from the control panel. I was no expert on arks, but I was pretty sure that Ferman was Bazian Orthodox. At some level this was just as crazy as believing in whatever Ganelial Crade believed, but it was a far more traditional and predictable form of crazy.

Still, if a group of religious fanatics had wanted to abduct a few carloads of avout, they couldn’t have done a slicker job of it. That’s why I snapped awake when I heard Ferman Beller mention God.

Until now he’d avoided it, which I could not understand. If you sincerely believed in God, how could you form one thought, speak one sentence, without mentioning Him? Instead of which Deolaters like Beller would go on for hours without bringing God into the conversation at all. Maybe his God was remote from our doings. Or—more likely—maybe the presence of God was so obvious to him that he felt no more need to speak of it than did I to point out, all the time, that I was breathing air.

Frustration was in Beller’s voice. Not angry or bitter. This was the gentle, genial frustration of an uncle who can’t get something through a nephew’s head. We seemed so smart. Why didn’t we believe in God?

“We’re observing the Sconic Discipline,” Arsibalt told him—happy, and a bit relieved, to’ve been given an opportunity to clear this up. He was too optimistic, I thought, too confident he could get Beller to see it our way. “It’s not the same thing as not believing in God. Though”—he hastily added—“I can see why it looks that way to one who’s never been exposed to Sconic thought.”

“I thought your Discipline came from Saunt Cartas,” said Beller.

“Indeed. One can trace a direct line from the Cartasian principles of the Old Mathic Age to many of our practices. But much has been added, and a few things have been taken away.”

“So, I guess Scone was another Saunt who added something?”

“No, a scone is a little cake.”

Beller chuckled in the forced, awkward way that extras did when someone told a joke that was not funny.

“I’m serious,” Arsibalt said. “Sconism is named after the little tea-cakes. It is a system of thought that was discovered about halfway between the Rebirth and the Terrible Events. The high-water mark of Praxic Age civilization, if you will. A couple of hundred years earlier, the gates of the Old Maths had been flung open, the avout had gone forth and mingled with the S#230;culars—mostly S#230;culars of wealth and status. Lords and ladies. The globe, by this point, had been explored and charted. The laws of dynamics had been worked out and were just beginning to come into praxic use.”

“The Mechanic Age,” Beller tried, dredging up a word he’d been forced to memorize in some suvin a long time ago.

“Yes. Clever people could make a living, in those days, just by hanging around in salons, discussing metatheorics, writing books, tutoring the children of nobles and industrialists. It was the most harmonious relationship between, er—”

“Us and you?” Beller suggested.

“Yes, that had existed since the Golden Age of Ethras. Anyway, there was one great lady, named Baritoe, whose husband was a philandering idiot, but never mind, she took advantage of his absence to run a salon in her house. All the best metatheoricians knew to gather there at a particular time of day, when the scones were coming out of her ovens. People came and went over the years, so Lady Baritoe was the only constant. She wrote books, but, as she herself is careful to say, the ideas in them can’t be attributed to any one person. Someone dubbed it Sconic thought and the name stuck.”

“And it all got incorporated into your Discipline, what, a couple of hundred years later?”

“Yes, not in a very formal way though. More as a set of habits. Thinking-habits that many of the new avout already shared when they came in the gates.”

“Such as not believing in God?” Beller asked.

And here—though we were driving on fair, level ground—I felt as I would’ve if we’d been on a mountain track with a thousand-foot cliff to one side, which Beller could have spilled us into with a twitch of the controls. Arsibalt was relaxed, though, which I marveled at, because he could be so high-strung about matters that were so much less dangerous.

“Studying this is sort of a pie-eating contest,” Arsibalt began.

This was a Fluccish expression that Lio, Jesry, Arsibalt, and I used to mean a long thankless trudge through a pile of books. It completely wrong-footed Beller, who thought we were talking of scones, and so here Arsibalt had to spend a minute or two disentangling these two baked-goods references.

“I’ll try to sketch it out,” Arsibalt continued, once they’d gotten back on track. “Sconic thought was a third way between two unacceptable alternatives. By then it was well understood that we do all of our thinking up here in our brains.” He tapped his head. “And that the brain gets its inputs from eyes, ears, and other sense organs. The naive attitude is that your brain works directly with the real world. I look at this button on your control panel, I reach out and feel it with my hand—”

“Don’t touch that!” Beller warned.

“I see

“That all seems pretty obvious,” Beller said.

Then there was an awkward silence, which Beller finally broke by saying—in good humor—“I guess that’s why you called it naive.”

“At the opposite extreme, there were those who argued that everything we think we know about the world outside of our skulls is an illusion.”

“Seems kind of smart-alecky more than anything else,” Beller said after considering it for a bit.

“The Sconics didn’t much care for it either. As I said, they developed a third attitude. ‘When we think about the world—or about almost

“Well, I guess I see the point. It doesn’t have that smart-aleckiness of the other one you mentioned. But it seems like a distinction without a difference,” Beller said.

“It’s not,” Arsibalt said. “And here is where the pie-eating contest would begin, if you wanted to understand

“There is no God?”

“No, something different, and harder to sum up, which is that certain topics are simply out of bounds. The existence of God is one of those.”

“What do you mean, out of bounds?”

“If you follow through the logical arguments of the Sconic system, you are led to the conclusion that our minds can’t think in a productive or useful way about God, if by God you mean the Bazian Orthodox God which is clearly not spatiotemporal—not existing in space and time, that is.”

“But God exists everywhere and in all times,” Beller said.

“But what does it really mean to say that? Your God is more than this road, and that mountain, and all the other physical objects in the universe put together, isn’t He?”

“Sure. Of course. Otherwise we’d just be nature-worshippers or something.”

“So it’s crucial to your definition of God that He is more than just a big pile of stuff.”

“Of course.”

“Well, that ‘more’ is by definition outside of space of time. And the Sconics demonstrated that we simply cannot think in a useful way about anything that, in principle, can’t be experienced through our senses. And I can already see from the look on your face that you don’t agree.”

“I don’t!” Beller affirmed.

“But that’s beside the point. The point is that, after the Sconics, the kinds of people who did theorics and metatheorics stopped talking about God and certain other topics such as free will and what existed before the universe. And that is what I mean by the Sconic Discipline. By the time of the Reconstitution it had become in-grained. It was incorporated into our Discipline without much discussion, or even conscious awareness.”

“Well, but with all the free time you’ve got—sitting there in your concents—couldn’t

“We have less free time than you imagine,” Arsibalt said gently, “but nevertheless, many people have devoted much thought to the matter, and founded Orders devoted to denying God, or believing in Him, and currents have surged back and forth in and among the maths. But none of it seems to have moved us away from the basic position of the Sconics.”

“Do you believe in God?” Beller asked flat-out.

I leaned forward, fascinated.

“I

“Doesn’t that go against the Sconic Discipline?” Beller asked.

“Yes,” Arsibalt said, “but that is perfectly all right, as long as one isn’t going about it in a naive way—as if Lady Baritoe had never written a word. A common complaint made about the Sconics is that they didn’t know much about pure theorics. Many theoricians, looking at Baritoe’s works, say ‘wait just a minute, there’s something missing here—we

“So you can see God by doing theorics?”

“Not God,” Arsibalt said, “not a God that any ark would recognize.”

After that he managed to change the subject. He—like I—had wondered what the Powers That Be might have told Ferman and the others when they had put out the call for volunteers.

The answer seemed to be: not much. The S#230;cular Power needed some sort of puzzle solved—the sort of thing that avout were good at. Some fraas and suurs would have to be moved from Point A to Point B so that they could work on this conundrum. People like Ferman Beller were naturally curious about us. They had all learned about the Reconstitution in their suvins, and they understood that we had an assigned role to play, however sporadically, in making their civilization work. They were fascinated to see the mechanism being invoked, at least once in their lives, and were proud to be a part of it even if they hadn’t a clue as to why it was being engaged.

In the hottest part of the afternoon we pulled off into the shade of a line of trees that had once served as wind-break for a farm compound, now collapsed. We hadn’t seen Crade in hours, but Cord’s fetch was right behind us. Some of us walked around and some dozed. The mountains darkened the northwestern sky, though if you didn’t know what they were you might mistake them for a storm front. On their opposite slope they caught most of the moisture blowing in from the ocean and funneled it into the river that ran through our concent. Consequently this side was arid. Only bunchgrass and low fragrant shrubs would grow here of their own accord. From age to age the S#230;cular Power would irrigate it and people would live here growing grain and legumes, but we were now on the wane of such a cycle, as was obvious from the condition of the roads, the farmsteads, and what were shown on the cartabla as towns. The old irrigation ditches were fouled by whatever would grow in them, which was mostly things with thorns, spines, and detachable burrs. Lio and I went for a brisk walk along one of these, but we didn’t say much as we were keeping an eye out for snakes.

Sammann kept looking as if he had something to say. We decided on a shake-up that put me and him in Cord’s fetch, while Lio and Barb went to Ferman’s mobe. Barb wanted to stay with Jad but we all knew that Jad must be getting a little weary of his company and so we insisted. Cord was tired of driving, so Rosk took the controls.

“Ferman Beller is communicating with a Bazian installation on one of those mountains,” Sammann told me.

This was an odd phrasing, since Baz had been sacked fifty-two hundred years ago. “As in Bazian Orthodox?” I asked.

Sammann rolled his eyes. “Yes.”

“A religious institution?”

“Or something.”

“How do you know this?”

“Never mind. I just thought you might want to know that Ganelial Crade isn’t the only one with an agenda.”

I considered asking Sammann what

My agenda was looking at the photomnenomic tablet, which I knew that everyone in this vehicle—except for Cord, who’d been driving—must have been studying. I’d only had a brief look at it before. Cord and I sat together in the back. The sun was shining in so we threw a blanket over our heads and huddled in the dark like a couple of kids playing campout.

This thing that Orolo had wanted so badly to take pictures of: would it be something that we would recognize as a ship? Until Sammann had showed me this tablet a few hours ago, all I had known was that it used bursts of plasma to change its velocity and that it could shine red lasers on things. For all I’d known, it could have been a hollowed-out asteroid. It could have been an alien life form, adapted to live in the vacuum of space, that shot bombs out of a sphincter. It could have been constructed out of things that we would not even recognize as matter; it could have been only half in this universe and half in some other. So I had made an effort to open my mind. I had been prepared to be confronted by some sort of image that I would not be able to understand at first. And it had, indeed, been a riddle. But not the kind of riddle I’d been expecting. I hadn’t had time to study it, to puzzle over it, at the time. Now I had a good long look.

The image was streaked in the direction of the ship’s motion. Fraa Orolo had probably set up the telescope to track it across the sky, but he’d had to make his best guess as to its direction and speed, and he hadn’t gotten it exactly right, hence the motion blur. I guessed that this was only the last in a series of such images that Orolo had been making during the weeks leading up to Apert, each slightly better than the last as he learned how to track the target and how to calibrate the exposure. Sammann had already applied some kind of syntactic process to the image to reduce the blur and bring out many details that would have been lost otherwise.

It was an icosahedron. Twenty faces, each of them an equilateral triangle. That much I’d seen when Sammann had first shown it to me. And therein lay the puzzle, because such a shape could be either natural or artificial. Geometers loved icosahedrons, but so did nature; viruses, spores, and pollens had all been known to take this shape. So perhaps it

“This thing can’t be pressurized,” I pointed out.

“Because the surfaces are all flat?” Cord said—more as statement than question. She dealt with compressed gases in her work, and knew in her bones that any vessel containing pressure must be rounded: a cylinder, a sphere, or a torus.

“Keep looking,” Sammann advised us.

“The corners,” Cord said, “the-what-do-you-call-’em—”

“Vertices,” I said. Those twenty triangular facets came together at twelve vertices; each vertex joined five triangles. These seemed to bulge outward a little. At first I’d mistaken this for blur. But on a closer look I convinced myself that each vertex was a little sphere. And this drew my eye to the edges. The twelve vertices were joined by a network of thirty straight edges. And those too had a rounded, bulging look to them—

“There they are!” said Cord.

I knew exactly what she meant. “The shock absorbers,” I said. For it was obvious, now: each of the thirty edges was a long slender shock absorber, just like the ones on the suspension of Cord’s fetch, except bigger. The frame of this ship was just a network of thirty shock absorbers that came together at a dozen spherical vertices. The entire thing was one big distributed shock absorption system.

“There must be ball-and-socket joints in the corners, to make that work,” Cord said.

“Yeah—otherwise the frame couldn’t flex,” I said. “But there’s a big part of this I’m not getting.”

“What are the flats made of? The triangles?” Cord said.

“Yeah. No point making a triangle out of things that can give, unless the stuff in the middle can give too—change its shape a little, when the shocks flex.” So we spent a while puzzling over the twenty flat, triangular surfaces that accounted for the ship’s surface area. These, I thought, looked a little funny. They looked rugged. Not smooth metal, but cobbled together.

“I could almost swear it’s stucco.”

“I was going to say concrete,” Cord said.

“Think gravel,” suggested Sammann.

“Okay,” Cord said, “gravel has some give to it where concrete doesn’t. But how’s it held together?”

“There are a lot of little rocks floating around up there,” I said. “In a way, gravel’s the most plentiful solid thing you can obtain in space.”

“Yeah, but—”

“But that doesn’t answer your question,” I admitted. “Who knows? Maybe they have woven some kind of mesh to hold them in place.”

“Erosion control,” Cord said, nodding.

“What?”

“You see it on the banks of rivers, where they’re trying to stop erosion. They’ll throw a bunch of rocks into a cube of wire mesh, then stack the cubes and wire ’em together.”

“It’s a good analogy,” I said. “You need erosion control in space too.”

“How do you figure?”

“Micrometeoroids and cosmic rays are always coming in from all directions. If you can surround your ship with a shell of cheap material—aka, gravel—you’ve cut down quite a bit on the problem.”

“Hey, wait a sec,” she said, “this one looks different.” She was pointing to one face that had a circle inscribed in it. We hadn’t noticed it at first, because it was around to one side, foreshortened, harder to make out. The circle was clearly made of different stuff: I had the feeling it was hard, smooth, and stiff.

“Not only that,” I pointed out, “but—”

She’d caught it too: “No shocks around this one.” The three edges outlining this face were sharp and simple.

“I’ve got it!” I said. “That one is the pusher plate.”

“The what?”

I explained about the atomic bombs and the pusher plate. She accepted this much more readily than any of us had. The ship that Lio had shown us in the book had been a stack: pusher plate, shocks, crew quarters. This one was an envelope: the outer shell was one large distributed shock absorber, as well as a shield. And, I was beginning to realize, a shroud. A veil to hide whatever was suspended in the middle.

Once we’d identified the pusher plate—the stern of the ship—our eyes were naturally drawn to the face on the opposite, or forward end: its prow. This was hidden from view. But one of the adjoining shock absorbers was visible. And something was written on it. Printed there neatly was a line of glyphs that had to be an inscription in some language. Some of the glyphs, like circles and simple combinations of strokes, could easily be mistaken for characters in our Bazian alphabet. But others belonged to no alphabet that I had ever seen.

And yet they were so close to our letters that this alphabet seemed almost like a sib of ours. Some of them were Bazian letters turned upside-down or reflected in a mirror.

I flung the blanket off.

“Hey!” Cord complained, and closed her eyes.

Fraa Jad turned around and looked me in the face. He seemed ever so slightly amused.

“These people”—I did not call them aliens—“are related to us.”

“We have started referring to them as the Cousins,” announced Fraa Criscan, the Hundreder sitting next to Fraa Jad.

“What could possibly explain that!?” I demanded—as if they could possibly know such a thing.

“These others have been speculating about it,” Fraa Jad said. “Wasting their time—as it is just a hypothesis.”

“How big is this thing—has anyone tried to estimate its dimensions?” I asked.

“I know that from the settings of the telescope and the tablet,” Sammann said “It is about three miles in diameter.”

“Let me spare you having to work it out in your head,” said Fraa Criscan, watching my face, mildly amused. “If you want to generate pseudogravity by spinning part of the ship—”

“Like those old doughnut-shaped space stations in spec-fic speelies?” I asked.

Criscan looked blank. “I’ve never seen a speely, but yes, I think we are talking about the same thing.”

“Sorry.”

“It’s okay. If you are playing that game, and you want to generate the same level of gravity we have here on Arbre—and if there is such a thing hidden inside of this icosahedron—”

“Which is kind of what I was imagining,” I allowed.

“Say it’s two miles across. The radius is one mile. It would have to spin about once every eighty seconds to provide Arbre gravity.”

“Seems reasonable. Doable,” I said.

“What are you talking about?” Cord asked.

“Could you live on a merry-go-round that spun once every minute and a half?”

She shrugged. “Sure.”

“Are you talking about where the Cousins came from?” shouted Rosk over his shoulder. He couldn’t understand Orth but he could pick out some words and he could read our tones of voice.

“We’re debating whether it is productive to have any such discussion at all,” I said, but that was a little too complicated, shouted from the back of the fetch over road noise.

“In books and speelies, sometimes you see a fictional universe where an ancient race seeded a bunch of different star systems with colonies that lost touch with each other afterwards,” Rosk volunteered.

The other avout in the vehicle looked as if they were biting their tongues.

“The problem is, Rosk, we have a fossil record—”

“That goes back billions of years, yeah, that is a problem with that idea,” Rosk admitted. From which I guessed that others had already torn this idea limb from limb before his eyes, but that Rosk liked it too much to let go of it—he’d never been taught Diax’s Rake.

Cord had put the blanket back over her head but she said, “Another idea that we were talking about earlier was, you know, the whole concept of parallel universes. Then Fraa Jad pointed out that this ship is quite clearly in

“What a killjoy,” I remarked—in Fluccish, obviously.

“Yeah,” she said. “It is a real drag hanging around with you people. So logical. Speaking of which—did you notice the geometry proof?”

“What?”

“They couldn’t stop talking about it, earlier.”

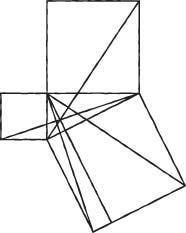

I ducked back under the blanket with her. She knew how to pan and zoom the image. She magnified one of the faces, then dragged it around until the screen was filled with something that looked like this, though a lot streakier and blurrier:

|

“That’s certainly a weird thing to put on your ship,” I said. I zoomed back out for a moment because I wanted to get a sense of where this diagram was located. It was centered on one of the icosahedron’s faces, adjoining, and just aft of, the one that we had identified as the bow. If the ship’s envelope was made of gravel, held in some kind of matrix, then this diagram had been built into this face as a sort of mosaic, by picking out darker pieces of gravel and setting them carefully into place. They’d put a lot of work into it.

“It’s their emblem,” I said. Only speculating. But no one spoke out against the idea. I zoomed back in and spent a while examining the network of lines. It was obviously a proof—almost certainly of the Adrakhonic Theorem. The sort of problem that fids worked all the time as an exercise. Just as if I were sitting in a chalk hall, trying to get the answer quicker than Jesry, I began to break it down into triangles and to look for right angles and other features that I could use to anchor a proof. Any fid from the Halls of Orithena probably would have gotten it by now, but my plane geometry was a little rusty—

I poked my head out from under the blanket, careful this time not to blind Cord.

“This is just plain creepy,” I said.

“That’s the same word Lio used!” Rosk shouted back.

“Why do you guys all think it’s creepy?” Cord wanted to know.

“Please supply a definition of the oft-used Fluccish word

I tried to explain it to the Thousander, but primitive emotional states were not what Orth was good at.

“An intuition of the numenous,” Fraa Jad hazarded, “combined with a sense of dread.”

“

Now I had to answer Cord’s question. I made a few false starts. Then I saw Sammann watching me and I got an idea. “Sammann here is an expert on information. Communication, to him, means transmitting a series of characters.”

“Like the letters on this shock absorber?” Cord asked.

“Exactly,” I said, “but since the Cousins use different letters, and have a different language, a message from them would look to us like something written in a secret code. We’d have to decipher it and translate it into our language. Instead of which the Cousins have decided here to—to—”

“To bypass language,” Sammann said, impatient with my floundering.

“Exactly! And instead they have gone directly to this picture.”

“You think they put it there for us to see?” Cord asked.

“Why else would you go to the trouble to put something on the

“I don’t understand it,” Cord protested.

“

With us who lived in concents, that is.

Roaming from star system to star system in a bomb-powered concent, making contact with their planet-bound brethren—

“Snap out of it, Raz!” I said to myself.

“Yes,” said Fraa Jad, who’d been watching my face, “please do.”

“They came,” I said, “the Cousins did, and the S#230;cular Power picked them up on radar. Tracked them. Worried about them. Took pictures of them. Saw that.” I pointed to the proof on Fraa Jad’s lap. “Recognized it as an avout thing. Got worried. Figured out that the ship had been detected—somehow—by at least one fraa: Orolo.”

“I told him about it,” Sammann said.

Sammann looked uncomfortable. But I had gotten it all so badly wrong that he couldn’t contain himself—he had to straighten me out. “A communication reached us from the S#230;cular Power,” he said.

“Us meaning the Ita?”

“A third-order reticule.”

“Huh?”

“Never mind. We were told to go in secret—bypassing the hierarchs—to the concent’s foremost cosmographer, and tell him of this thing.”

“And then what?”

“There were no further instructions,” Sammann said.

“So you chose Orolo.”

Sammann shrugged. “I went to his vineyard one night while he was alone, cursing at his grapes, and told him this—told him I had stumbled across it while reviewing logs of routine mail-protocol traffic.”

I didn’t understand a word of his Ita gibberish but I got the gist of it. “So, part of your orders from the S#230;cular Power were to make it seem that this was just you, acting on your own—”

“So that they could later deny that they had anything to do with it,” Sammann said, “when it came time to crack down.”

“I doubt that they were so premeditated,” Fraa Jad put in, using a mild tone of voice, as Sammann and I had become heated—conspiratorial. “Let us get out the Rake,” Jad went on. “The S#230;cular Power had radar, but not pictures. To get pictures they needed telescopes and people who knew how to use them. They did not want to involve the hierarchs. So they devised the strategy that Sammann has just explained to us. It was only a means of getting some pictures of the thing as quickly and quietly as possible. But when they

“And then they realized that they’d made a big mistake,” I said, in a much calmer tone than before. “They had divulged the existence and nature of the Cousins to the last people in the world they’d want to know about them.”

“Hence the closure of the starhenge and what happened to Orolo,” Sammann said, “and hence me in this fetch, as I have no idea what they’ll want to do to

I’d assumed until now that Sammann had obtained permission to go on this journey. This was my first hint that it was more complicated than that. I found it strange to hear an Ita voicing fear of getting in trouble, since usually it was

“So you made this copy of the tablet and kept it so that you would have—”

“And you showed yourself in Clesthyra’s Eye. Announcing, in a deniable way, that you knew something—that you had information.”

“Advertising,” Sammann said, and the shape of his face changed, whiskers shifting on whiskers—his way of hinting at a smile.

“Well, it worked,” I said, “and here you are, on the road to nowhere, being driven around by a bunch of Deolaters.”

Cord got fed up with hearing Orth and moved up to the front of the fetch to sit with Rosk. I felt sorry—but some things were nearly impossible to talk about in Fluccish.

I was dying to ask Fraa Jad about the nuclear waste, but was reluctant to broach this topic with Sammann listening. So I drew my own copy of the proof on the Cousins’ ship and began working it. Before long I got bogged down. Cord and Rosk started playing some music on the fetch’s sound system, softly at first, more loudly when no one objected. This had to be the first time Fraa Jad had ever heard popular music. I cringed so hard I thought I’d get internal injuries. But the Thousander accepted it as calmly as he had the Dynaglide lubri-strip. I gave up trying to work the proof, and just looked out the window and listened to the music. In spite of all of my prejudices against extramuros culture, I kept being surprised by moments of beauty in these songs. Most of them were forgettable but one in ten sheltered some turn or inflection that proved that the person who had made it had achieved some kind of upsight—had, for a moment, got it. I wondered if this was a representative sampling, or if Cord was just unusually good at finding songs with beauty in them and loading only those onto her jeejah.

The music, the heat of the afternoon, the jouncing of the fetch, my lack of sleep, and shock at leaving the concent—with all of these affecting me at once, it was no wonder I couldn’t work a proof. But as the day grew old and the sun came in more and more horizontally, as the dying towns and ruined irrigation systems came less and less frequently and the landscape was purified into high desert, spattered with stony ruins, I started thinking that something else was working on me.

I was used to Orolo being dead. Not literally dead and buried, of course, but dead to me. That was what Anathem did: killed an avout without damaging the body. Now, with only a few hours to get used to the idea, I was about to see Orolo again. At any moment, for all I knew, we might spy him hiking up one of these lonely crags to get ready for a night’s observations. Or perhaps his emaciated corpse was waiting for us under a cairn thrown up by slines descended from those who’d eaten Saunt Bly’s liver. Either way, it was impossible for me to think of anything else when I might be confronted by such a thing at any moment.

Cord’s face was shining on me. She reached for a control and turned down the music, then repeated something. I had gone into a sort of trance, which I shattered by moving.

“Ferman’s on the jeejah,” she explained. “He wants to stop. Pee and parley.”

Both sounded good to me. We pulled off at a wide place in the road along a curving grade, a third of the way into a descent that would, over the next half-hour, take us into a flat-bottomed valley that connected to the horizon. This was no valley of the wet and verdant type, but a failure in the land where withered creeks went to die and flash floods spent their rage on a supine waste. Spires and palisades of brown basalt hurled shadows much longer than they were tall. Two solitary mountains rose up perhaps twenty or thirty miles away. We gathered around the cartabla and convinced ourselves that those were two of the three candidates we’d chosen earlier. As for the third—well, it appeared that we had just driven around it and were now scouring its lower slopes.

Ferman wanted to talk to me in my capacity as leader. I shook off the last wisps of the near-coma I had sunk into, and drew myself up straight.

“I know you guys don’t believe in God,” he began, “but considering the way you live, well, I thought you might feel more at home staying with—”

“Bazian monks?” I hazarded.

“Yes, exactly.” He was a little taken aback that I knew this. It was only a lucky guess. When Sammann had mentioned earlier that Ferman was talking to a “Bazian installation,” I had imagined a cathedral or at any rate something opulent. But that was before I’d seen the landscape.

“A monastery,” I said, “is on one of those mountains?”

“The closer of the two. You can see it about halfway up, on the northern flank.”

With some hints from Ferman I was able to see a break in the mountain’s slope, a sort of natural terrace sheltered under a crescent of dark green: trees, I assumed.

“I’ve been there for retreats,” Ferman remarked. “Used to send my kids there every summer.”

The concept of a retreat didn’t make sense to me until I realized that it was how I lived my entire life.

Ferman misinterpreted my silence. He turned to face me and held up his hands, palms out. “Now, if you’re not comfortable, let me tell you we have enough water and food and bedrolls and so on that we can camp anywhere we like. But I was thinking—”

“It’s reasonable,” I said, “if they’ll accept women.”

“The monks have their own cloister, separate from the camp. But girls stay at the camp all the time—they have women on the staff.”

It had been a long day. The sun was going down. I was tired. I shrugged. “If nothing else,” I said, “it might make for a good story or two, for us to tell when we get to Saunt Tredegarh.”

Lio and Arsibalt had been hovering. They pounced on me as soon as Ferman Beller started to walk away. They both had the somewhat tense and frayed look of people who’d just spent several hours cooped up with Barb. “Fraa Erasmas,” Arsibalt began, “let’s be realistic. Look at this landscape! There’s no way anyone could live here on his own. How would one obtain food, water, medical care?”

“Trees are growing on one place on that mountain,” I said. “That probably means that there is fresh water. People like Ferman send their kids here for summer camp—how bad can it be?”

“It’s an oasis!” Lio said, having fun whipping out this exotic word.

“Yeah. And if the nearer butte has an

“That doesn’t solve the problem of getting food,” Arsibalt pointed out.

“Well, it’s an improvement on the picture that I’ve been carrying around in my head,” I said. I didn’t have to explain this to the others because they’d had it in their heads too: desperate men living on the top of a mountain, eating lichens.

“There must be a way,” I continued, “the Bazian monks do it.”

“They are a larger community, and they are supported by alms,” Arsibalt said.

“Orolo told me that Estemard had been sending him letters from Bly’s Butte for years. And Saunt Bly managed to live there for a while—”

“Only because slines worshipped him.” Lio pointed out.

“Well, maybe we’ll find a bunch of slines bowing down to Orolo then. I don’t know how it works. Maybe there’s a tourist industry.”

“Are you joking?” Arsibalt asked.

“Look at this wide spot in the road where we are stopped,” I said.

“What of it?”

“Why do you suppose it’s here?”

“I haven’t the faintest idea, I’m not a praxic,” Arsibalt said.

“So that vehicles can pass each other more easily?” Lio guessed.

I held out my arm, drawing their attention to the view. “It’s here because of that.”

“What? Because it’s beautiful?”

“Yeah.” And then I turned away from Arsibalt and looked at Lio, who started to walk away. I fell in alongside him. Arsibalt stayed behind to examine the view, as if he could discover some flaw in my logic by staring at it long enough.

“Did you get a chance to look at the icosahedron?” Lio asked me. “Yeah. And I saw the proof—the geometry.”

“You think these people are like us. That they will be sympathetic to our point of view as followers of Our Mother Hylaea,” he said, trying these phrases on me for size.

I was already defensive—sensing a flank maneuver. “Well, I think that they are clearly trying to get at

“The ship is heavily armed,” he said.

“Obviously!”

He was already shaking his head. “I’m not talking about the propulsion charges. They’d be almost useless as weapons. I’m talking about other things on that ship—things that become obvious when you look for them.”

“I didn’t see anything that looked remotely like a weapon.”

“You can hide a lot of equipment on a mile-long shock absorber,” he pointed out, “and who knows what’s concealed under all that gravel.”

“Can you give me an example?”

“The faces have regularly spaced features on them. I think that they are antennas.”

“So? Obviously they’re going to have antennas.”

“They are phased arrays,” he said. “Military stuff. Just what you’d want to aim an X-ray laser, or a high-velocity impactor. I’ll need to consult books to know more. Also, I don’t like the planets lined up on the nose.”

“What do you mean?”

“There’s a row of four disks painted on a forward shock. I think that they are depictions of planets. Like on a military aerocraft of the Praxic Age.”

It took me a few moments to sort out the reference. “Wait a minute, you think that they are

Lio shrugged.

“Well, now, hold on a second!” I said. “Couldn’t it be that it’s something more benign? Maybe those are the home planets of the Cousins.”

“I just think that everyone is too eager to look for happy, comforting interpretations—”

“And your role as a Warden Fendant-in-the-making is to be way more vigilant than that,” I said, “and you’re doing a great job.”

“Thanks.”

We walked along silently for a little while, strolling up and down the length of this wide place, occasionally passing others who were taking the opportunity to get a little bit of exercise. We happened upon Fraa Jad, who was walking alone. I decided that now was the moment.

“Fraa Lio,” I said, “Fraa Jad has informed me that the Millenarian math at Saunt Edhar is one of three places where the S#230;cular Power put all of its nuclear waste around the time of the Reconstitution. The other two are Rambalf and Tredegarh. Both of them were illuminated last night by a laser from the Cousins’ ship.”

Lio wasn’t as surprised by this as I’d hoped. “Among Fendant types there is a suspicion that the Three Inviolates were allowed to remain unsacked for a reason. One hypothesis is that they are dumps for Everything Killers and other dangerous leftovers of the Praxic Age.”