"The Winter Ghosts" - читать интересную книгу автора (Mosse Kate)

The Man in the Mirror

|

When I got back to my room after a long, hot soak in the bath, a fire was burning in the grate, releasing an aroma of pine resin into the room. The smell snapped at my heart strings, taking me back to Sussex winters when I was a boy, with George home from school for the holidays.

Madame Galy had brought a brass-handled oil lamp with a round wick burner and bulging glass chimney, and set it on the table. A tray with a glass and heavy-bottomed bottle had also appeared on the chest of drawers.

It was all very congenial, snug.

My trousers were draped over a wooden clothes horse set at an angle in front of the fire. I rubbed the heavy tweed between my fingers. Still damp, but well on the way to being wearable. My slipover was on a lower rung, the arms dangling down, and my socks were drying on the hearth, the toes, where the wool was thickest, pointing towards the flames. Of my overcoat, cap and boots there was no sign, nor of my shirt. It occurred to me that Madame Galy was soaking it to try to shift the blood on the collar.

She had been as good as her word and found clothes for me to borrow. Rather, a costume. I picked up the tunic of rough cotton from the bed, and smiled. The sleeves only reached the elbow, there was no collar and there were ties at the neck in place of buttons. It was much like the sort of thing I’d once worn for a particularly dreadful school production of

I’d been to a couple of costume parties in London in the days after the War had ended and before my nerves got the better of me. I had enjoyed them. I liked the anonymity of disguise, for a few hours pretending to be a man of action from history or the pages of a novel. A Shackleton or a Quatermain.

I was still stiff from the accident, so eased the tunic carefully over my shoulders, then stepped back to take a look at myself in the mirror. Dressed as a peasant with my hair sticking up as nature intended, I was hardly Mr Rider Haggard’s hero. But I was pleased enough.

I looked closer and felt something shift inside me, for, despite the cracks and breaks on the bevelled surface, staring back at me from the mirror was a reflection I had not thought to see again. Myself. Or, rather, the person I might have been had not grief marked me. The lines of loss, of illness, were still there. I was too pale and thin, that was undeniable, and my green eyes were perhaps a little too bright. But the features were familiar. My old self was making its way to the surface. Freddie Watson, younger son of George and Anne Watson, Crossways Lodge, Lavant, Sussex.

I looked a while longer, happy in my own company, until my bare feet started to ache with cold. I hurried to finish dressing. Madame Galy had left no trousers to match the tunic, so I presumed she intended me to wear my own. The turn-ups were still a little damp, but they’d do. I slipped them on, buttoned the fly, then thumped down on the bumpy mattress to investigate the footwear that had been left in place of my boots.

I examined them in the light cast by the oil lamp. They, too, had a theatrical look. Soft leather boots with no heels or fastenings. They set my memories racing once more. A family outing one Christmas when Mother took George and me to see

I looked down at the boots in my hand. They were precisely the kind of things the boy playing Peter had worn. I could hear George in my ear, joshing me for even contemplating putting on such footwear.

‘A step too far, old chap, a step too far,’ he’d have said. I could hear the dry humour, the inflection of his voice. His words poking me in the ribs.

‘A step too far, not bad,’ I said. ‘Not bad at all.’

I felt the smile slip. The truth of it was that these words belonged to me, not George. I so wanted to hear him talking to me in that low, wry way of his, the distinctive fall at the end of every sentence, that charming, cracked tone partway between boredom and brilliance. But however hard I tried to keep my end of the bargain, the conversation was always one-sided.

Was it in that little room in Nulle that the realisation struck me? How I’d fallen into the habit of ascribing every witty, clever aphorism to George? How I’d stepped out of my own life and into the wings, yielding centre-stage to him? Or was it something I already knew but had not wanted to acknowledge?

But I do know that, as I let the leather costume boots drop from my hand to the floor, I was aware of something slipping away from me. Of something being lost.

‘An awfully big adventure,’ I muttered.

I sat for a moment longer, then strode over to the chest of drawers and poured myself two fingers from the bottle. It was a thick, red liqueur, and I swallowed it down in one gulp. A little sweet for my taste, it nonetheless hit the back of my throat with a kick. Heat flooded my chest. I poured another double measure. Again, I downed it in one. The alcohol knocked the edge off things. I was reluctant now to leave the warm cocoon of the room. Taking a cigarette from my case, I tapped the tobacco tight and paced the room as I smoked, this time enjoying the texture of the cold wood beneath my bare feet. Thinking about the day, thinking about things.

I flicked the end of the cigarette into the fire, then crouched down to see how my socks were doing. The movement set the room spinning.

‘Food,’ I muttered. ‘I need food.’

They were dry, though stiff as a board, and I rubbed and stretched at the wool before pulling them on. The boots were tight, and looked rather peculiar matched with tweed trousers, but not otherwise too bad a fit.

I was ready. I gathered up my bits and pieces from the chest of drawers, and took the hand-drawn map Madame Galy had left as promised. Then, with a last look around the room, I picked up the letter and went out into the cold corridor.

There was no one downstairs, though the oil lamps were burning. I put the letter in plain view on the high reception counter then, leaning across it, I called into the gloom of the back rooms beyond.

‘

There was no answer. As I drew back, I saw I had left the imprint of my hands on the polished wood. The problem was I had not thought to ask how I should get back in to the boarding house later. Would I need a latchkey? Should I ring the bell or would the door be unlocked?

‘Monsieur Galy, I’m off now,’ I called again.

There was still no response. I hesitated, then slipped round behind the desk and replaced the room key on its hook so he would see that I had gone.

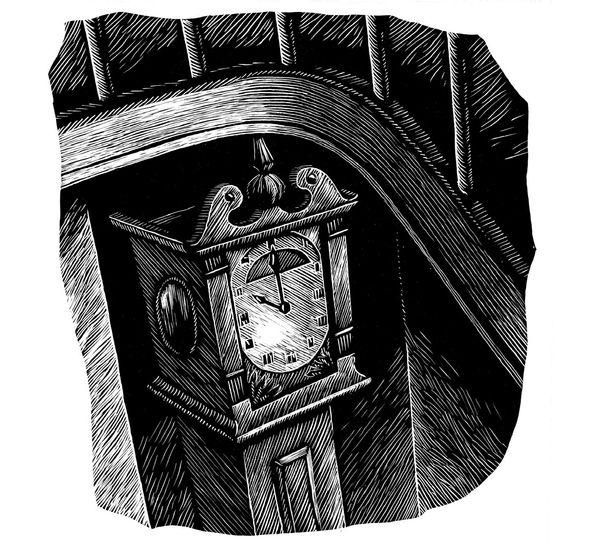

An antique tall case-clock with a mahogany surround stood in the alcove beneath the sweep of the stairs. I looked up at the mottled, ivory-coloured face, at the slim Roman numerals and delicate black hands. There was a whirring of the mechanism inside the case, then a high-pitched carillon started to chime.

|

I knew I’d taken my time but, even so, I was surprised that it was ten o’clock already. In the sanatorium, sedated by my physicians, whole days had passed in the blinking of an eye. On other occasions, blunted by the medicines they force-fed me morning and night, the world seemed to limp to a standstill. Even so, had seven whole hours really gone by since first I’d arrived at the boarding house? No wonder I was hungry.

My overcoat was hanging on a hook on the wall beside the front entrance. I shrugged myself into it, put on my cap, then I pulled open the heavy door and stepped out into the night.

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |