"The Winter Ghosts" - читать интересную книгу автора (Mosse Kate)

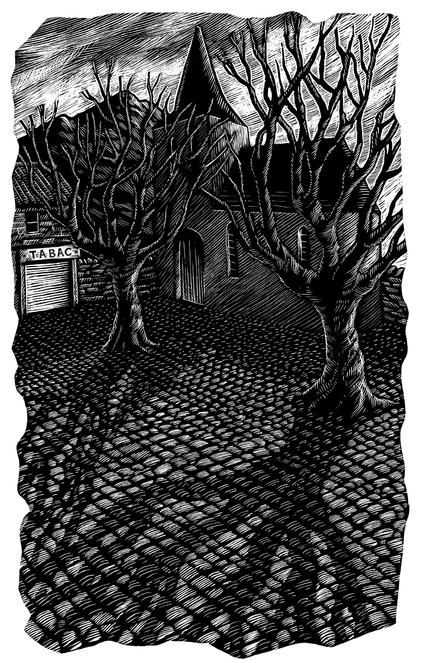

The Village of Nulle

|

The storm had clearly passed over the valley, leaving it untouched, for there was no snow at all on the road or the roof tiles.

I walked slowly, trying to get the measure of the place. I passed a handful of low buildings which looked like stores or animal pens. Drips of water had frozen along the guttering in rows of icy daggers pointing sharply down at the hard ground below. Notwithstanding the fearsome cold, the village seemed oddly deserted. No boys with delivery carts selling milk and butter. No post office vans. In the houses, I saw an occasional shadow move in and out of the slivers of light that slipped out between partially open shutters, but no one out and about. Once I thought I heard footsteps behind me, but when I turned, the street was empty. Other sounds were rare – a dog barking and a strange, repetitive noise, like the rattling of wood against the cobbles – and vanished into the mist as quickly as they had come. After a while, I began to wonder if I had imagined them.

I walked further. Then my ears picked out what sounded like the bleating of sheep, though I knew that was unlikely in December. I’d been told of the twice-yearly fête de la transhumance, the festival in September to mark the departure of the men and flocks to winter pastures in Spain, then again in May, to celebrate their safe return. Throughout the upper river valleys of the Pyrenees, this was a fixture on the annual calendar, a time-honoured tradition of which they were proud. More than once I’d heard the Spanish slopes described as the ‘

The houses grew more substantial and the condition of the road improved, though still I saw no one. On the end walls of the buildings were tattered advertising boards promoting soap or own-brand cigarettes or aperitifs, and ugly telephone wires stretched between the buildings. Everything in Nulle seemed drab and half-hearted. The colours on the posters were bleached and dull, the paper peeling at the corners. Rust flaked from the metal fixings on the wall that held the wires in place. But there was something about the stillness of the afternoon light, the ambience of being down-at-heel, that I liked, like a photograph of a once-fashionable destination that had now grown old and tired. I felt oddly at home in this forgotten village, with its air of having been left behind.

By now I had arrived at the heart of the village, the place de l’Église. I tipped my cap back on my head – the snow had seeped through to the headband and was making my forehead itch in any case – and took stock. In the centre of the square was a stone well, a pail dangling from a black wrought-iron rail that arched across it. From where I stood, I could see a

My eye was drawn by a narrow building, larger than the rest, with a wooden sign hanging on the wall. A boarding house or hotel, perhaps? I walked quickly across the square towards it. Three wide stone steps led up to a low wooden door, beside which hung a brass bell. Its thick rope twisted in the currents of cold air, round and round. A hand-painted board above the door announced the name of the proprietors: M amp; MME GALY.

|

I hesitated, conscious of the fact that I looked pretty disreputable. The cut on my cheek was no longer bleeding, but I had specks of dried blood on my collar, my clothes were wet and I had no luggage to recommend me. I looked wretched. I straightened my scarf, pushed my stained handkerchief and gloves down into the pockets of my overcoat and adjusted my cap.

I tugged on the bell and heard it ring deep inside the house. At first, nothing happened. Then I heard footsteps inside, coming closer, and the sound of a bolt being drawn back.

A snaggle-toothed old man, in a flat-collared shirt, a waistcoat and heavy brown country trousers peered out. White hair framed a lined, weather-beaten face.

‘

I asked if there might be a room for the night. Monsieur Galy, or so I assumed, looked me up and down, but did not speak. Assuming my French was at fault, I pointed down at my wet clothes, the wound on my cheek, and began to explain about the accident on the mountain road.

‘

Without taking his eyes from my face, he shouted over his shoulder into the silence of the corridor behind him.

‘

From the gloom of the passageway, a stout middle-aged woman appeared, her wooden

Galy waved his hand to indicate I should explain once more. Again, I began to recite the litany of mishaps that had led me to Nulle. I did not mention the hunters.

To my relief, Madame Galy seemed to understand. After a brief and rattling conversation with her husband in a heavy dialect too thick for me to follow, she said of course they could provide a room for the night. She would also, she added, arrange for someone to accompany me into the mountains tomorrow to retrieve the automobile.

‘There is no one who could help now?’ I asked.

She gave an apologetic shrug and gestured over my shoulder. ‘It is too late.’

I turned and was astonished to see that, in the few minutes we’d been talking, dusk had stolen the remains of the day. I was on the point of remarking upon it, when Madame Galy continued to explain that, in any case, this particular day in December was the most important annual celebration of the year,

‘

I smiled. ‘In which case, tomorrow it is.’

And I was reassured. No doubt, here was the reason for the strange, hushed silence of the village, for all the shops being closed, for the queer burning

Beckoning for me to follow, Madame Galy clattered down the corridor. Monsieur Galy shut the front door and bolted it behind us. When I glanced back over my shoulder, he was still standing there frowning, his arms hanging loose by his sides. He seemed unhappy about the appearance of an unexpected guest, but I wasn’t going to let it bother me. I was here. Here I would stay.

There was a round switch for an electric light on the wall, but no bulbs in the ceiling fittings. Instead, the passage was lit by oil lamps, their small flames magnified by curved glass shades.

‘You have no power?’

‘The supply is not reliable, especially in winter. It comes and goes.’

‘But there is hot water?’ I asked. Now I was out of the cold, I was able to admit how utterly done in I was. My thighs and calves ached from my trek down into the village and I was chilled right through. More than anything, I wanted a long, warm bath.

‘Of course. We have an oil heater for that.’

We continued down the long corridor. I glanced into rooms where the doors stood open. All were empty. There were no sounds of conversation, of servants going about their duties.

‘Do you have many other guests?’

‘Not at present.’

I waited for her to elaborate, but she did not, and despite my curiosity, I did not press the point.

Madame Galy stopped in front of a high wooden desk at the foot of the stairs. I caught the smell of beeswax polish, a sharp reminder of the back stairs leading up to my childhood attic nursery that were so dangerous for boys in stockinged feet.

‘

She pushed an ancient register towards me. Leather binding, heavy cream paper with narrow blue feint lines. I glanced at the names above mine and saw that the last entries were in September. Had there been no one since then? I signed my name all the same. Formalities accomplished, Madame Galy chose a large, old-fashioned brass key from a row of six hooks on the wall, then took a lighted candle from the counter.

‘

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |