"The Whispering Land" - читать интересную книгу автора (Durrell Gerald)

Chapter Seven

VAMPIRES* AND WINE

On my return from Oran the garage almost overflowed with animals. One could scarcely make oneself heard above the shrill, incomprehensible conversations of the parrots, the harsh rattling cries of the guans, the incredibly loud trumpeting of the seriemas, the chattering of the coatimundis, and an occasional dull rumble, as of distant thunder, from the puma, whom I had christened Luna in the human Luna's honour. As a background to this there was a steady scrunching noise that came from the agouti cage, for it was always engaged in trying to do alterations to its living quarters with its chisel-like teeth.

As soon as I had got back I had begun constructing cages for all our various creatures, leaving the caging of Luna until last, for she had travelled in a large packing-case that gave her more than enough room to move about in. However, when all the other animals were housed, I set about building a cage worthy of the puma, which, I hoped, would show off her beauty and grace. I had just finished it when Luna's godfather* arrived, singing lustily as usual, and offered to help me in the tricky job of getting Luna to pass from her present quarters into the new cage. We carefully closed the garage doors so that, if anything untoward happened, the cat would not go rampaging off across the countryside and be lost. It also had the advantage, as the human Luna pointed out, that we would be locked in with her, a prospect he viewed with alarm and despondency. I soothed his fears by telling him that the puma would be far more frightened than we were, and at that moment she uttered a rumbling growl of such malignance and fearlessness that Luna paled visibly. My attempt to persuade him that this growl was really an indication of how afraid the animal was of us was greeted with a look of complete disbelief.

The plan of campaign was that the crate in which the puma now reposed would be dragged opposite the door of the new cage, a few slats removed from the side, and the cat would then walk from the crate into the cage without fuss. Unfortunately owing to the somewhat eccentric construction of the cage I had built, we could not wedge the crate close up to the door: there was a gap of some eight inches between crate and cage. Undeterred, I placed planks so that they formed a sort of short tunnel between the two boxes, and then proceeded to remove the end of the crate so that the puma could get out. During this process a golden paw, that appeared to be the size of a ham, suddenly appeared in the gap and a nice, deep slash appeared across the back of my hand.

"Ah!" said Luna gloomily, "you see, Gerry?"

"It's only because she's scared of the hammering," I said with feigned cheerfulness sucking my hand. "Now, I think I've removed enough boards for her to get through. All we have to do is wait."

We waited. After ten minutes I peered through a knot hole and saw the wretched puma lying quietly in her crate, drowsing peacefully, and showing not the slightest interest in passing down our rickety tunnel and into her new and more spacious quarters. There was obviously only one thing to do, and that was to frighten her into passing from crate to cage. I lifted the hammer and brought it down on the back of the crate with a crash. Perhaps I should have warned Luna. Two things happened at once. The puma, startled out of her half-sleep, leapt up and rushed to the gap in the crate, and the force of my blow with the hammer knocked down the piece of board which was forming Luna's side of the tunnel. In consequence he looked down just in time to see an extremely irritable-looking puma sniffing meditatively at his legs. He uttered a tenor screech, which I have rarely heard equalled, and leapt vertically into the air. It was the screech that saved the situation. It so unnerved the puma that she fled into the new cage as fast as she could, and I dropped the sliding door, locking her safely inside. Luna leant against the garage door wiping his face with a handkerchief.

"There you are," I said cheerfully, "I told you it would be easy."

Luna gave me a withering look. "You have collected animals in South America and Africa?" he inquired at length. "That is correct?" "Yes."

"You have been doing this work for fourteen years?" "Yes."

"You are now thirty-three?" "Yes."

Luna shook his head, like a person faced with one of the great enigmas of life.

"How you have lived so long only the good God knows," he said.

"I lead a charmed* life," I said. "Anyway, why did you come to see me this morning, apart from wanting to wrestle with your namesake?"

"Outside," said Luna, still mopping his face, "is an Indian with a

"I think it is a pig," said Luna, "but it's in a box and I can't see it very clearly."

The Indian was squatting on the lawn, and in front of him was a box from which issued a series of falsetto squeaks and muffled grunts. Only a member of the pig family could produce such extraordinary sound. The Indian grinned, removed his big straw hat, ducked his head, and then, removing the lid of the box, drew forth the most adorable little creature. It was a very young collared peccary,* the common species of wild pig that inhabits the tropical portions of South America.

"This is Juanita," said the Indian, smiling as he placed the diminutive creature on the lawn, where it uttered a shrill squeak of delight and started to snuffle about hopefully.

Now, I have always had a soft spot for the pig family,* and baby pigs I cannot resist, so within five minutes Juanita was mine at a price that was double what she was worth, speaking financially, but only a hundredth part of what she was worth in charm and personality. She was about eighteen inches long and about twelve inches high, clad in long, rather coarse greyish fur, and a neat white band that ran from the angle of her jaw up round her neck, so that she looked as though she was wearing an Eton collar.* She had a slim body, with a delicately tapered snout ending in a delicious retrousse* nose (somewhat like a plunger), and slender, fragile legs tipped with neatly polished hooves the circumference of a sixpence. She had a dainty, lady-like walk, moving her legs very rapidly, her hooves making a gentle pattering like rain.

She was ridiculously tame, and had the most endearing habit of greeting you – even after only five minutes' absence – as if you had been away for years, and that, for her, these years had been grey and empty. She would utter strangled squeaks of delight, and rush towards you, to rub her nose and behind against your legs in an orgy of delighted reunion, giving seductive grunts and sighs. Her idea of Heaven was to be picked up and held on her back in your arms, as you would nurse a baby, and then have her tummy scratched. She would lie there, her eyes closed, gnashing her baby teeth together, like miniature castanets, in an ecstasy of delight. I still had all the very tame and less destructive creatures funning loose in the garage, and as Juanita behaved in such a lady-like fashion I allowed her the run of the place* as well, only shutting her in a cage at night.

|

At feeding time it was a weird sight to see Juanita, her nose buried in a large dish of food, surrounded by an assortment of creatures – seriemas parrots, pigmy rabbits, guans – all trying to feed out of the same dish. She always behaved impeccably, allowing the others plenty of room to feed, and never showing any animosity, even when a wily seriema pinched titbits from under her pink nose. The only time I ever saw her lose her temper was when one of the more weak-minded of the parrots, who had worked himself into a highly excitable state at the sight of the food plate, flew down squawking joyously, and landed on Juanita's snout. She shook him off with a grunt of indignation and chased him, squawking and fluttering, into a corner, where she stood over him for a moment, champing her teeth in warning, before returning to her interrupted meal.

When I had got all my new specimens nicely settled, I paid a visit to Edna to thank her for the care and attention she had lavished on my animals in my absence. I found her and, Helmuth busy with a huge pile of tiny scarlet peppers, with which they were concocting a sauce of Helmuth's invention, an ambrosial* substance which, when added to soup, removed the roof of your mouth with the first swallow, but added a flavour that was out of this world.* An old boot, I am sure, boiled and then covered with Helmuth's sauce, would have been greeted with shouts of joy by any gourmet.*

"Ah, Gerry," said Helmuth, rushing to the drink cupboard. "I have got good news for you."

"You mean you've bought a new bottle of gin?" I inquired hopefully.

"Well, that of course," he said grinning. "We knew you were coming hack. But apart from that do you know that next week-end is a holiday?"

"Yes, what about it?"

"It means," said Helmuth, sloshing gin into glasses with gay abandon, "that I can take you up the mountains of Calilegua for three days. You like that, eh?"

I turned to Edna.

"Edna,"I began, "I love you…"

"All right," she said resignedly, "but you must make sure* the puma can't get out, that is all I insist upon." So, the following Saturday morning, I was awoken, just as dawn was lightening the sky, by Luna, leaning through my window and singing a somewhat bawdy love-song. I crawled out of bed, humped my equipment on to my back, and we made our way through the cool, aquarium light of dawn to Helmuth's flat. Outside it was a group of rather battered-looking horses, each clad in the extraordinary saddle that they use in the north of Argentina. The saddle itself had a deep, curved seat with a very high pommel in front, so that it was almost like an armchair to sit in. Attached to the front of the saddle were two huge pieces of leather, shaped somewhat like angel's wings which acted as wonderful protection for your legs and knees when you rode through thorn scrub. In the dim dawn light the horses, clad in their weird saddles, looked like some group of mythical beasts, Pegasus* for example, grazing forlornly on the dewy grass. Nearby lounged a group of four guides and hunters who were to accompany us, delightfully wild and unshaven-looking, wearing dirty

At first we rode along the rough tracks that ran through the sugar-cane fields, where the canes whispered and clacked in the slight breeze. Our hunters and guides had cantered on ahead, and Luna and I and Helmuth rode in a row, keeping our horses at a gentle walk, Helmuth was telling me the story of his life, how at the age of seventeen (as an Austrian) he had been press-ganged* into the German Army, and had fought through the entire war, first in North Africa, then Italy and finally in Germany, without losing anything except the top joint of one finger, which was removed by a land-mine that blew up under him and should have killed him. Luna merely slouched in his great saddle, like a fallen puppet, singing softly to himself. When Helmuth and I had settled world affairs generally, and come to the earth-shaking* conclusion that war was futile we fell silent and listened to Luna's soft voice, the chorus of canes, and the steady clop of our horses' hooves, like gentle untroubled heart-beats in the fine dust.

Presently the path left the cane fields and started to climb up the lower slopes of the mountain, passing into real forest. The massive trees stood, decorated with trailing epiphytes* and orchids,* each one bound to its fellow by tangled and twisted lianas,* like a chain of slaves. The path had now taken on the appearance of an old watercourse (and in the rainy season I think this is what it must have been) strewn with uneven boulders of various sizes, many of them loose. The horses, though used to the country and sure-footed,* frequently stumbled and nearly pitched you over their heads, so you had to concentrate on holding them up unless you suddenly wanted to find yourself with a split skull. The path had now narrowed, and twisted and turned through the thick undergrowth so tortuously that, although the three of us were riding almost nose to tail, we frequently lost sight of each other, and if it had not been for Luna's voice raised in song behind me, and the occasional oaths from Helmuth when his horse stumbled, I could have been riding alone. We had been riding this way for an hour or so, occasionally shouting Comments or questions to each other, when I heard a roar of rage from Helmuth, who was a fair distance ahead. Rounding the corner I saw what was causing his rage.

The path at this point had widened, and along one side of it ran a rock-lined ravine, some six feet deep. Into this one of our pack horses had managed to fall, by some extraordinary means known only to itself, for the path at this point was more than wide enough to avoid such a catastrophe. The horse was standing, looking rattier smug I thought, in the bottom of the ravine, while our wild-looking hunters had dismounted and were trying to make it climb up on to the path again. The whole of one side of the horse was covered with a scarlet substance that dripped macabrely,* and the animal was standing in what appeared to be an ever-widening pool of blood. My first thought was to wonder, incredulously, how the creature had managed to hurt itself so badly with such a simple fall, and then I realised that the pack that the horse was carrying contained, among other things, part of our wine supply. The gooey* mess and Helmuth's rage were explained. We eventually got the horse back up to path, and Helmuth peered into the wine-stained sack, uttering moans of anguish.

"Bloody horse," he said, "why couldn't it fall on the

"Anything left?" I asked. "No," said Helmuth, giving me an anguished look, "every bottle broken. Do you know what that means, eh?"

"No," I said truthfully. "It means we have only twenty-five bottles of wine to last us," said Helmuth. Subdued by this tragedy we proceeded on our way slowly. Even Luna seemed affected by our loss, and sang only the more mournful songs in his extensive repertoire.

We rode on and on and on, the path getting steeper and steeper. At noon we dismounted by a small, tumbling stream, our shirts black with sweat, bathed our-selves and had a light meal of raw garlic, bread and wine. This, to the fastidious, may sound revolting, but when you are hungry there is no finer combination of tastes. We rested for an hour, to let our sweat-striped horses dry off, and then mounted again and rode on throughout the afternoon; At last, when the evening shadows were lengthening and we could see glimmers of a golden sunset through tiny gaps in the trees above, the path suddenly flattened out, and we rode into a flat, fairly clear area of forest. Here we found that our hunters had already dismounted and unsaddled the horses, while one of them had gathered dry brushwood and lighted a fire. We dismounted stiffly, unsaddled our horses and then, using our saddles and woolly sheepskin saddle-cloth, called a

Presently, feeling a bit less stiff, and as there was still enough light left, I decided to have a walk round the forest in the immediate area of our camp. Very soon the gruff voices of the hunters were lost among the leaves as I ducked and twisted my way* through the tangled, sunset-lit undergrowth. Overhead an occasional humming-bird flipped and purred in front of a flower for a last-night drink, and small groups of toukans* flapped from tree to tree, yapping like puppies, or contemplating me with heads on one side; wheezing like rusty hinges. But it was not the birds that interested me so much as the extraordinary variety of fungi* that I saw around me. I have never, in any part of the world, seen such a variety of mushrooms and toadstools littering the forest floor, the fallen tree-trunks, and the trees themselves. They were in all colours, from wine-red to black, from yellow to grey, and in a fantastic variety of shapes. I walked slowly for about fifteen minutes in the forest, and in that time I must have covered an area of about an acre. Yet in that short time, and in such a limited space, I filled my hat with twenty-five different species of fungi. Some were scarlet, shaped like goblets of Venetian glass* on delicate stems; others were filigreed with holes, so that they were like little carved ivory tables in yellow and white; others were like great, smooth blobs of tar or lava, black and hard, spreading over the rotting logs, and others appeared to have been carved out of polished chocolate, branched and twisted like clumps of miniature stag's antlers. Others stood in rows, like red or yellow or brown buttons on the shirt-fronts of the fallen trees, and others, like old yellow sponges, bung from the branches, dripping evil yellow liquid. It was a

Soon, it became too dark to see properly between the trees, and I made my way back to camp, spread out my fungi in rows, and examined them by the firelight. The unsavoury-looking meat had by now turned into the most delicious steaks, brown and bubbling, and we each with our own knife kept leaning forward cutting any delicate slivers away from the steaks, dunking them in Helmuth's sauce (a bottle of which he had thoughtfully brought with him) and popping the fragrant result into our mouths. Except for an occasional belch the silence was complete. The wine was passed silently, and occasionally someone would lean forward and softly rearrange the logs on the fire, so that the flames flapped upwards more brightly, and the remains of the steaks sizzled briefly, like a nest of sleepy wasps. At last, surfeited with food, we lay back against the comfortable hummocks of our saddles, and Luna, after taking a deep pull at the wine bottle, picked up his guitar and started to strum softly. Presently, very gently, he started to sing, his voice scarcely travelling beyond the circle of firelight, and the hunters joined him in a deep, rich chorus. I put on my poncho (that invaluable garment like a blanket with a hole in the middle), wrapped myself tightly in it – with one hand free to accept the wine bottle as it drifted round the circle – rolled my sheepskin

I awoke, still staring up into the sky, which was now a pale blue, suffused with gold. Turning on my side I saw the hunters already up, the fire lit, and more strips of meat hung to cook. Helmuth was crouching by the fire drinking a huge mug of steaming coffee, and he grinned at me as I yawned.

"Look at Luna," he said., gesturing with his cup, "snoring like a pig."

Luna lay near me, completely invisible under his poncho. I extricated my leg from my own poncho and licked vigorously at what I thought was probably Luna's rear end. It was, and a yelp greeted my cruelty. This was followed by a giggle and a burst of song as Luna's head appeared through the hole in his poncho, making him look ridiculously like a singing tortoise emerging from its shell. Presently, warmed by coffee and steaks, we saddled up and rode off into the forest, damp and fragrant with dew, and alive with ringing bird-calls.

As we rode my mind was occupied with the subject of vampire bats. I realised that, in the short time at our disposal up the mountains, we had little chance of catching any really spectacular beasts, but I knew that our destination was infested with these bats. At one time an attempt had been made to start a coffee plantation up where we were going, but no horses could be kept because of the vampires, and so the project had been abandoned. Now, I was extremely keen to meet a vampire on its home ground, so to speak, and, if possible, to catch some and take them back to Europe with me, feeding them on chicken's blood, or, if necessary, my own or that of any volunteers I could raise. As far as I knew they had never been taken back to any European zoo, though some had been kept successfully in the United States. I only hoped that, after being so long neglected, all the vampires at the coffee farm had not moved on to more lucrative pastures.

Our destination, when we reached it an hour or so later, proved to be a dilapidated one-roomed hut, with a small covered verandah running along one side. I gave it approximately another six months before it quietly disintegrated and became part of the forest: we had obviously only just arrived in time. All the hunters, Helmuth and Luna, treated this hut as though it was some luxury hotel, and eagerly dragged their saddles inside and argued amicably over who should sleep in which corner of the worm-eaten floor. I chose to sleep out on the verandah, not only because I felt it would be a trifle more hygienic, but from there I could keep an eye on the tree to which the horses were tethered, for it was on them that I expected the bats to make their first attack.

After a meal we set off on foot into the forest, but, although we saw numerous tracks of tapir arid jaguar and lesser beasts, the creatures themselves remained invisible. I did manage, however, by turning over every rotten log we came across, to capture two nice little toads, a tree-frog and a baby coral snake, the latter much to everyone's horror. These I stowed away carefully in the linen bags brought for the purpose when we returned to our hut for the evening meal. When we had finished we sat round the glowing remains of the fire, and Luna, as usual, sang to us. Then the rest of them retired into the hut, carefully closing the window and the door so that not a breath of deadly night air should creep in and kill them (though they had slept out in it quite happily the night before), and I made up my bed on the verandah, propped up so that i could get a good view of the horses, silvered with moonlight, tethered some twenty feet away. I settled myself comfortably, lit a cigarette, and then sat there straining my eyes into the moonlight for the very first sign of a bat anywhere near our horses. I sat like this for two hours before, against my will, dropping off to sleep.

I awoke at dawn, and furious with myself for having slept, I struggled out of my poncho and went to inspect the horses: I discovered, to my intense irritation, that two of them had been attacked by vampires while I lay snoring twenty feet away. They had both been bitten in exactly the same place, on the neck about a hand's length from the withers. The bites themselves consisted of two slits, each about half an inch long and quite shallow. But the effect of these small bites was quite gruesome, for the blood (as in all vampire bites) had not clotted after the bat had finished licking up its grisly meal and flown off, for the vampire's saliva contains an anticoagulant.* So, when the bloated bat had left its perch on the horses' necks, the wounds had continued to bleed, and now the horses' necks were striped with great bands of clotted blood, out of all proportion to the size of the bites. Again I noticed that the bites, as well as being in identical positions on each horse, were also on the same side of the body, the right side of the animal if you were sitting on it, and there was no sign of a bite or an attempted bite on the left side of either horse. Both animals seemed quite unaffected by the interest I was taking in them.

After breakfast; determined that the vampire bats must be lurking somewhere nearby, I organised the rest of the party in a search. We spread out and hunted through the forest in a circle round the hut, going about a quarter of a mile deep into the forest, looking for hollow trees or small caves where the vampires might be lurking. We continued in this fruitless task until lunch-time, and when we reassembled at the hut the only living specimens we could really be said to have acquired were some three hundred and forty black ticks* of varying ages and sizes, who, out of all of us, seemed to have preferred the smell of Luna and Helmuth, and so had converged on them. They had to go down to the stream nearby and strip; then, having washed the more tenacious ticks off their bodies, they set about the task of removing the others from the folds and crannies of their clothing, both of them perched naked on the rocks picking at their clothes like a couple of baboons.

"Curious things, ticks," I said conversationally, when I went down to the stream to tell them that food was ready, "parasites of great perception. It's a well-known natural history fact that they always attack the more unpleasant people of the party… usually the drunks, or the ones of very low mentality or morals."

Luna and Helmuth glared at me.

"Would you," inquired Helmuth interestedly, "like Luna and me to throw you over that waterfall? "

"You must admit it's a bit peculiar. None of our hunters got ticks, and they are all fairly good parasite-bait, I would have thought. I didn't get ticks. You two were the only ones. You know the old English proverb about parasites?"

"What old English proverb?" asked Helmuth suspiciously.

"Birds of a feather flock together "* I said, and hurried back to camp before they could get their shoes on and follow me.

The sun was so blindingly hot in the clearing when we had finished eating that everyone stretched out on the minute verandah and had a siesta. While the others were all snoring like a covey of pigs, I found I could not sleep. My head was still full of vampires. I was annoyed that we had not found their hideout, which I felt sure must be somewhere fairly near. Of course, as I realised, there may have been only one or two bats, in which case looking for their hideout in the local forest was three times as difficult as the usual imbecile occupation of looking for needles in haystacks. It was not until the others had woken, with grunts and yawns, that an idea suddenly occurred to me. I jumped to my feet and went inside the hut. Looking up I saw, to my delight, that the single room had a wooden ceiling, which meant that there must be some sort of loft between the apex of the roof and the ceiling. I hurried outside and there, sure enough, was a square opening which obviously led into the space between roof and ceiling. I was now convinced that I should find the loft simply stuffed with vampire bats, and so I waited impatiently while the hunters fashioned a rough ladder out of saplings and hoisted it up to the hole. Then I sped up it, armed with a bag to put my captures in and a cloth to catch them with without being bitten. I was followed by Helmuth who was going to guard the opening with an old shirt of mine. Eagerly, holding a torch in my mouth, I wriggled into the loft. The first discovery I made was that the wooden ceiling on which I was perched was insecure in the extreme, and so I had to spread myself out like a starfish to distribute my weight, unless I wanted the whole thing to crash into the room below, with me on it. So, progressing on my stomach in the manner of a stalking Red Indian,* I set out to explore the loft.

The first sign of life was a long, slender tree-snake,* which shot past me towards the hole that Helmuth was guarding. When I informed him of this and asked him to try and catch it he greeted this request in the most unfriendly manner, interspersed with a number of rich Austrian oaths. Luckily for him, the snake found a crack in the ceiling and disappeared through that, and we did not see him again. I crawled on doggedly, disturbing three small scorpions, who immediately rushed into the nearest holes, and eight large and revolting spiders of the more hirsute variety, who merely shifted slightly when the torch beam hit them, and crouched there meditatively. But there was not the faintest sign of a bat, not even so much as a bat dropping* to encourage me. I was just beginning to feel very bitter about bats in general and vampire bats in particular, when my torch-beam picked out something sitting sedately on a cross-beam, glaring at me ferociously, and I immediately forgot all about vampires.

|

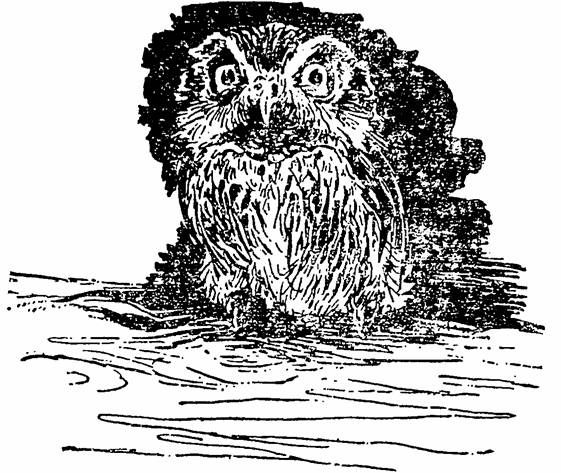

Squatting there in the puddle of torchlight was a pigmy owl, a bird little bigger than a sparrow, with round yellow eyes that glared at me with all the silent indignation of a vicar who, in the middle of the service, has discovered that the organist is drunk. Now, I have a passion for owls of all sorts, but these pigmy owls are probably my favourites. I think it is their diminutive size combined with their utter fearlessness that attracts me; at any rate I determined to add the one perching above me to my collection, or die in the attempt. Keeping the torch beam firmly fixed on his eyes, so that he could not see what I was doing, I gently brought up my other hand and then, with a quick movement, I threw the cloth I

To my surprise the hunters were excited and delighted with my capture of the pigmy owl. I was puzzled by this, until they explained that it was a common belief in Argentina that if you possessed one of these little birds you would be lucky in love. This answered a question that had been puzzling me for some time. When I had been in Buenos Aires I had found one of these owls in a cage in the local bird market. The owner had asked a price that was so fantastic that I had treated it with ridicule, until I realised that he meant it. He refused to bargain, and was quite unmoved when I left without buying the bird. Three days later I had returned, thinking that by now the man would be more amenable to bargaining, only to find that he had sold the owl at the price he had asked for. This had seemed to me incredible, and I could not for the life of me think of a satisfactory explanation. But now I realised I had been outbid by some lovesick swain;* I could only hope that the owl brought him luck.

That night was to be our last spent in the mountains, and I was grimly determined that I was going to catch a vampire bat if one showed so much as a wing-tip that night. I had even decided that I would use myself as bait. Not only would it bring the bats within catching range, but I was interested to see if the bite was really as painless as it was reputed to be. So, when the others had retired to their airless boudoir,* I made up my bed as near to the horses as I felt I could get without frightening off the bats, wrapped myself up in my poncho but left one of my feet sticking out, for vampires, I had read, were particularly fond of human extremities, especially the big toe. Anyway, it was the only extremity* I was prepared to sacrifice for the sake of Science.

I lay there in the moonlight, glaring at the horses, while my foot got colder and colder. I wondered if vampires like frozen human big toe.* Faintly from the dark forest around came the night sounds, a million crickets doing endless carpentry work in the undergrowth, hammering and sawing, forging miniature horseshoes, practising the trombone, tuning harps, and learning how to use tiny pneumatic drills. From the tree-tops frogs cleared their throats huskily, like a male chorus getting ready for a concert. Everything was brilliantly lit by moonlight, including my big toe, but there was not a bat to be seen.

Eventually, my left foot began to feel like something that had gone with Scott* to the Pole, and had been left there, so I drew it into the warmth of the poncho and extended my right foot as a sacrifice. The horses, with drooping heads, stood quite still in the moonlight, very occasionally shifting their weight from one pair of legs to another. Presently, in order to get some feeling back into my feet, I went and hobbled round the horses, inspecting them with the aid of a torch. None of them had been attacked. I went back and continued my self-imposed torture. I did a variety of things to keep myself awake: I smoked endless cigarettes under cover of the poncho, I made mental lists of all the South American animals I could think of, working through the alphabet, and, when these failed and I started to feel sleepy, I thought about my overdraft.* This last is the most successful sleep eradicator I know. By the time dawn had started to drain the blackness out of the sky, I was wide awake and feeling as though I was solely responsible for the National Debt.* As soon as it became light enough to see without a torch I hobbled over to inspect the horses, more as a matter of form than anything. I could hardly believe my eyes for two of them were painted with gory ribbons of blood down their necks. Now, I had been watching those horses – in brilliant moonlight – throughout the night, and I would have staked my life that not a bat of any description had come within a hundred yards of them. Yet two of them had been feasted upon, as it were, before my very eyes. To say that I was chagrined is putting it mildly. I had feet that felt as if they would fall off at a touch, a splitting headache, and felt generally rather like a dormouse that had been pulled out of its nest in mid-October.

Luna and Helmuth, of course, when I woke them up, were very amused, and thought this was sufficient revenge for my rude remarks the previous day about parasites. It was not until I had finished my breakfast in a moody and semi-somnambulistic state, and was starting on my third mug of coffee, that I remembered something that startled me considerably. In my enthusiasm to catch a vampire bat, and to be bitten by one to see what it felt like, I had completely forgotten the rather unpleasant fact that they can be rabies* carriers, so being bitten by one might have had some interesting repercussions, to say the least. I remembered that the rabies vaccine (which, with the usual ghoulish medical relish, they inject into your stomach) is extremely painful, and you have to have a vast quantity of the stuff pumped into you before you are out of danger. Whether this is necessary, or simply because the doctors get a rake-off* from the vaccine manufacturers, I don't know, but I do know – from people that have had it – that it is not an experience to be welcomed. The chances of getting rabies from a bat in that particular area would be extremely slight, I should have thought, but even so, had I been bitten, I would have had to undergo the injections as a precautionary measure; anyone who has ever read a description of the last stages of a person suffering from rabies would be only too happy to rush to the nearest hospital.

So, without bats or bites, and with my precious pigmy owl slung round my neck in a tiny bamboo cage, we set off down the mountains back to Calilegua. By the time we reached the cane fields it was green twilight, and we were all tired and aching. Even Luna, riding ahead, was singing more and more softly. At length we saw the glow of lights from Helmuth's flat, and when we dismounted, stiff, sweaty and dirty, and made our way inside, there was Edna, fresh and lovely, and by her side a table on which stood three very large ice-cold gin-and-tonics.

|

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |