"Teasing Secrets from the Dead: My Investigations at America's Most Infamous Crime Scenes" - читать интересную книгу автора (Craig Emily)

2. Death and Decay

THE FIRST THING I noticed was the smell-a sweet, almost musty odor, such a subtle part of the light spring breeze ruffling our hair that I couldn't quite tell where it came from.

I was following closely in the footsteps of Murray Marks, the guide on my first trip to the infamous Body Farm. This was always the first rite of passage for any grad student in the forensic anthropology program-a trip out to the small field and hardwood forest behind the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Knoxville.

Suddenly, Murray stopped and nodded toward the ground at my feet. Murray was tall and handsome, with dark-brown hair and soulful brown eyes, and I was happy to follow his gaze, but I could see only a black stain hidden in the tall grass. No, wait, there was more. If I looked closely at the mucky matrix of soil, dead foliage, and thousands of small brown pellets, I could see something else-the barely discernable bones of a human forearm.

I did everything I could to keep my face composed, though I'm sure I didn't fool Murray for a second. This skeleton was different from any I had seen in my medical career. The bones seemed to have soaked up the wetness and color of the soil, with bits of dark gray-brown sinew clinging to their ends in a futile attempt to hold them together at the joints. Where the larger joints had not yet come apart it looked as though someone had frozen a Halloween skeleton marionette in the middle of a wild dance: the legs splayed at the knees, one foot turned in as the other stuck straight up with curled toes, one arm folded awkwardly behind the neck while the other reached for something far off in the grass. The skull was there, but it appeared to be on backwards-the face was hidden in the dirt, while the jawbone rested at a strange angle within the chest cavity.

“How long do you think that body's been here?” Murray asked.

I looked again. Until today, I had only known bones as part of a whole, linked by the wires that keep a laboratory teaching skeleton intact, or as a dynamic living framework connected by ligaments. After death, though, those tissues begin to decay, and soon there is quite literally nothing to hold the bones together. Now I could see that when a corpse is laid out on the ground, gravity sucks the bones downward so that the skeleton eventually collapses, settling into earth made soft and soggy from the decaying tissues. What once was a rib cage becomes a flat row of rib bones, while the spine turns into a collection of disarticulated vertebrae. Of course, the skull and jawbone-mandible, to use the technical term-are easy to spot, but the tiny ligaments that hold our teeth in place also go the way of all flesh. Unless the root's shape keeps it stuck inside the socket, the teeth fall out, too.

“How long has it been here?” Murray repeated.

I took a closer look. The two forearm bones-the radius and ulna-had come completely detached from each other, and there wasn't a single bit of flesh on either the hand bones or the skull. “Six months?” I guessed.

Murray laughed.

“Nine months?” I ventured. “A year?”

He laughed again. “Two weeks,” he told me.

“Two weeks?”

“Because of the maggots.”

“The

Later I would learn that these little creatures have helped solved many murders. Now, though, I was blissfully unaware that those maggots were a huge part of what lay in store for me as a forensic anthropologist. Murray watched with amusement as I tried to lean closer to see the skull without letting the toes of my brand-new running shoes actually touch anything that seemed even faintly maggot-related.

As Murray and I left the decaying human remains, he explained to me a little of the Body Farm's history. In the early 1970s, the program's chair, Dr. William Bass, ran into a roadblock as he tried to solve a case involving a decomposed body. His interest in the process of human decay was piqued when he realized that, amazingly, no one had ever studied this process before, despite its obvious usefulness in forensic investigation. He also knew that U.T. Knoxville didn't have a modern skeletal collection for him to teach osteology or to use as a forensic anthropology database. The school did have a good collection of bones from Native American archaeological sites, but these were too different in size and shape to be of much use in current forensic research.

So Bass asked the University of Tennessee to give him a small section of land where he could leave human bodies to decompose under natural conditions and then gather the bones for his collection. After all, nature's method of stripping a carcass is fast and efficient, and it doesn't cost a cent. People who had donated their bodies to science found their way onto the Body Farm; so did unidentified and unclaimed corpses from the local medical examiner. Nature did its work-and Dr. Bass and his graduate students were able to document the processes by which bodies decay.

Until Dr. Bass came along, forensic scientists who were asked to establish time since death of a badly decomposed or skeletonized body had to rely upon guesswork and experience, laboriously comparing each new case with earlier solved cases. Now, thanks to Dr. Bass's pioneering work, we have documented scientific studies to back up our hunches. Despite the obvious advantages to this method of study, the University of Tennessee at Knoxville is still the only place in the world where scientists can observe and document the day-to-day journey from death to skeletonization.

Now, as Murray and I walked out from the woods full of corpses into the open field, I saw his look of approval. I hadn't fainted or gasped in horror-on the contrary, I'd been fascinated, drawing nearer for a closer look, even asking an intelligent question or two. All things considered, I'd approached the dead body like a scientist rather than a voyeur-and I realized that I had passed a test. True, I'd seen Murray 's slides and heard his descriptions at his lecture the summer before. But I had to admit, seeing the real thing was something else.

As Murray steered me over to two white cars and opened the trunks to see how the newest body-decay project was going, I couldn't help feeling just a bit triumphant. I knew that Dr. Bass had insisted that I-like all other incoming grad students-be taken out to the decay facility as soon as possible. If I wasn't prepared to deal with decomposing bodies-and with all other aspects of death and decay-it was best to find out now. Well, so far so good. But what other tests were in store for me?

|

I soon found out. Within only a few weeks, I was told to design and carry out a short-term research project of my own. Since I'd come to the university with an avid interest in facial reconstruction, I thought it would be interesting to document the changes in a person's face as he or she decayed. While still in Georgia, I'd been asked to “restore” faces that were in various stages of decomposition and I'd had some success, both with traditional drawing techniques and with experimental computer enhancement. In my naïveté, I thought that once I established some predictable baseline parameters for facial decomposition, all I'd have to do was take a photo of a dead person's face and perform a simple computer maneuver to make him or her look alive again.

I was wrong. Okay, I was right in theory-but only if I got to the body within the first day and a half. After that, if it was warm and humid enough, the maggots would have done their work and the face would be irrevocably altered, making any photos totally useless for identification purposes.

However, I was still interested in documenting what happened as maggots destroyed a face and, as luck would have it, I got my chance the very next day, when a newly donated body arrived at our lab just hours after the man had died. I positioned the man carefully on his back out in the open field, not too far from the wooded area. Securing his head with a rock on either side, I spread the camera tripod right over his shoulders and pointed the lens down toward his face at a ninety-degree angle. To my satisfaction, I was able to get a shot in before the first fly had landed.

For the next four days and nights, I returned to the body, remounted the camera, and took a new picture-every four hours. I scaled back to every six hours for the next ten days after that. May in Tennessee is indeed hot and humid, so the flies had laid their eggs the same day I put the body there, and by the next afternoon, the man's nose and mouth were bulging with baby maggots and fly eggs. In the middle of the following night, under the stark beam of my flashlight, his lips seemed to move as if he were trying to speak-I even thought I heard him moaning. No, those sounds were mine, involuntary responses to the sight of what had once been a human face being devoured from the inside out.

It took everything I had to focus the camera and zoom in on the maggot masses that were churning inside this man's mouth and nose and under his eyelids, creating this roiling, seething motion as they fed. Lines of ants were streaming up from the ground, ready to devour any maggots unlucky enough to be pushed out toward the edge of the teeming mass. It was a little unnerving to realize that however much we like to think we're at the top of the food chain while we're alive, once we're dead, we're just part of it.

After I left the facility that night, I went home and quickly poured a therapeutic dose of bourbon over a few ice cubes. As I sat on my back porch, drinking slowly and trying to regain some composure, I seriously doubted if I was cut out for this kind of work.

I managed to sleep for a few hours, but my dreams were filled with crawling maggots and voracious ants. At dawn, back at the facility, two startled vultures who had been trying to disembowel a nearby body flew to the trees directly over my head. As they took off slowly and clumsily from their breakfast, they followed their usual practice of spewing vomit on rapid takeoff-vomit that fell at my feet and over my corpse's torso. Meanwhile, slimy trails of the snails who had visited the carcass during the predawn hours now crisscrossed my subject's face, and his cheeks spewed adolescent maggots who seemed to be growing bigger right before my eyes. Maggots were pouring from his nostrils, too, and they had almost finished snacking on the last traces of his eyeballs, leaving empty sockets in his skull. Stifling a sigh, I forced myself to step over this man's body and set up my tripod.

|

Entomologists analyze maggots, adult flies, other insects, and similar small scavengers to estimate when and where a person died, and to help determine the types of injuries a victim has suffered. Adult flies-the very same houseflies that buzz around your picnic dinner-can sense death immediately. They are drawn to a body within a few minutes of when death occurs and, if they have access to the carcass, they land and start surveying the territory. Appearances to the contrary, when they crawl around on the body, they aren't eating much-just looking for the ideal place to lay their eggs. The tiny eggs, which resemble little clumps of sawdust, hatch into maggots within a day or two. The maggots immediately start to devour the carcass, growing visibly bigger with each passing day.

At first they don't even resemble the fat, stubby little legless larvae with soft white skin that most people visualize when they hear the word. Maggots have to go through three developmental stages, or “instars.” Their pale, white, papery skin splits and they shed it each time, until finally these mobile, voracious little eating machines have passed from infancy through their teenage days to reach their full growth potential.

Then, when they just can't eat any more, they crawl away from the dead body to find a place to hide. Their soft white skin becomes a dark-brown pupa casing, or shell, shaped something like a miniature football about one-fourth to one-half inch long, within which they metamorphose into adult flies-much as a caterpillar changes into a butterfly within a cocoon. If the weather stays warm and humid, the adult fly breaks open the end of its shell after a week or two, and the cycle is complete. At that point, if by any chance there's anything left of the body, the cycle begins again-and then again. If the entomologist can calculate the cycle, he or she can help you estimate when the dead body was first exposed to the elements.

Time of death is just one of the factors an entomologist helps to determine. Since the insects and other arthropods (spiders, mites, centipedes) commonly found on bodies have preferred habitats, sometimes an entomologist can tell if a person was moved after he or she was killed. If a corpse found in Florida is colonized by a species found only in New Jersey and parts north, the authorities are likely to include the possibility that the body was brought in from someplace else.

Sometimes maggots can even help you figure out whether a person sustained any injuries at the time of death. When the adult flies lay their eggs, they seek out the sites that provide the best environment for their young. In the human body, that would be the mouth, nose, ears, eyes, and genitals-warm, moist, and dark. The flies burrow as far as they can into those tempting, secret places and lay their eggs. In a decaying corpse, therefore, you would expect to see early maggot concentrations there-and if they've congregated anywhere else, perhaps another body part was broken or bloody at the time of death.

What still amazes me is how quickly maggots can reduce a fleshy corpse to bone. That childhood rhyme of “The worms crawl in, the worms crawl out” is not far wrong. There's a saying among forensic entomologists: Three flies and their offspring can consume a carcass as quickly as can a full-grown lion. Not bad for tiny creatures less than an inch long.

By the time I finished my time-lapse portrayal of decay, I was no longer fazed by sights-and smells-that two weeks ago had left me nauseated and trembling. Somehow, the shocking had become commonplace, and the human remains I saw rotting in the sun had begun to look more like three-dimensional puzzles and less like once-living beings. As I would later learn, this kind of detachment had its price-but it was also the necessary precondition for doing this work. If I was ever to learn to estimate the postmortem interval-how long it had been since someone had died-or to read the story of a person's last hours in a few broken bones, I would have to look at human remains as though I were a disembodied representative of science, not as a woman whose own body would one day end up rotting in the ground like everybody else's.

I still don't like maggots, though. Never have. Never will.

|

“I have a new challenge for you, class,” said Dr. Bass. On his desk he placed a metal cafeteria-style tray filled with a collection of human bones.

“I must confess,” he went on, “I don't have high hopes. In twenty years, no one has ever gotten this one right.”

I'd just finished a semester of Bill Bass's osteology class, where he'd done his best to initiate me and a dozen other grad students into the science of bone. Now we were taking the next giant step into the mysteries of forensic anthropology.

Forensic anthropologists take what we as physical anthropologists have learned about bone and apply it to criminal investigations. In the ideal world, physical anthropologists can look at a skeleton and tell you several basic pieces of information: age, race, sex, and stature. They can probably also tell you something about bone diseases and trauma-broken bones, healed injuries, and other evidence of how the person may have lived or died.

Of course, most anthropologists are usually working with centuries-old skeletons. We forensic anthropologists do the same kind of work-but on people who may have died only a few years, months, or even days ago. Our work may also involve fresh but unassociated body parts-the kind normally encountered in high-impact plane crashes or explosions-as well as corpses partially destroyed by fire.

As part of our academic training, my classmates and I were required to study cultural anthropology and theory of archaeology, and I'd struggled mightily through those classes. But I got my reward when it was finally time to learn about bone. No two ways about it, bone fascinated me.

True, Dr. Bass was an incredibly demanding professor, which I must admit I resented at first, particularly since, at Dr. Hughston's clinic, I'd been considered something of a bone expert myself. I soon came to find out, though, that it wasn't the same at all. The bones at the clinic might be broken or even crushed-but they were always safely encased within a recognizable portion of the human anatomy, always connected to their neighboring bones just as nature intended. As a forensic anthropologist, I would not always have the luxury of whole bones. A murderer might deliberately shatter his victims' bones, or a dog, bear, or coyote might crunch the bones between its teeth. And fire could reduce a human skeleton to mere fragments with devastating efficiency.

As a result, Dr. Bass insisted that we be able to instantly identify small fragments of bone, as well as the whole bones that are standard fare in most anatomy and anthropology classes. This seemed like a daunting challenge at first, but we soon learned that all bones have identifying features that make them unique, distinguishing each bone from every other and even separating right from left. For example, the metacarpals-the bones extending from the palm of the hand-all look alike at first glance, but if you look at the end that joins the wrist bones, you can see that each has a slightly different shape.

Once we'd learned the secrets of each individual bone, we had to be able to look at a fragment and pick out the one feature that would help us identify it. The mandibular condyle, for instance, is a tiny part of the jawbone that fits into the corresponding groove of the skull-no bigger than a plump raisin. It has a shape that is unlike any other piece of the human skeleton, and once its image is firmly anchored in your mind, you can not only recognize it, you can tell which side of the jaw it comes from, even if the rest of the jaw is missing.

As soon as we started to feel the first glimmer of confidence in our ability to identify adult skeletal material, we had to step back in time and learn how these bones looked while they were still growing. The bones of newborns and infants were a wonder to behold, but the differences in shape and size from adult bones added yet another element of confusion. Soon I learned, though, that even the tiniest bones had a distinctive shape that resembled at least a portion of their adult counterparts.

The skull is incredibly difficult to understand in its infant form, and even adult skulls are tough to deal with when they're fragmented. Almost everyone can recognize the familiar shape of a complete human skull, but together the cranium and the face contain over two dozen separate components. Big, relatively flat bones form the back, top, and sides of the skull, with smaller, more complex bones surrounding the eyes and face. In decomposed or skeletonized infants, these bones are thin, incompletely formed, and not connected at all, looking more like big, irregular restaurant-style corn chips than human bones. Again, Dr. Bass insisted that we know skull fragments backward and forward. He knew, and we were soon to learn, that the skull is a favorite target of murderers.

I must admit, it took me a while to hit my stride in osteology class-the way an anthropologist looks at bones is simply so different from the way an orthopedic surgeon views them. I was used to seeing bones live and whole, within a huge organic structure of which they were only a small though vital part-not as isolated elements that might be found scattered in a field or piled in the corner of a basement.

But once we moved from whole-bone identification to the analysis of fragments, my competitive spirit came through. My friend and fellow student, Tyler O'Brien, would sneak into the osteology lab with me each night, and we spent hours quizzing each other on every fragment in the collection. First we learned by sight-“Half of a right patella.” “Portion of a lumbar vertebra.” Then we shut our eyes and set ourselves to learning by touch alone the unique characteristics of each bone.

That process had taken months-but it had served us well. Both of us, as well as most of the class, could now take the merest glance at a whole bone and tell you what it was and which side of the body it came from. We could pick up the smallest fragment and find the key to its identity. Solving these intricate three-dimensional puzzles became a new and thrilling game.

Soon we were ready for an even more fascinating task-applying this knowledge to forensic anthropology analyses. Now, though, it was no longer a game. We were being taught to practice on real cases-albeit cases that had been solved years before. But our subjects were real people who had died violent deaths. It was up to us to figure out who they were and what had happened to them.

The routine was always the same. Dr. Bass would bring a collection of bones into the classroom on Tuesday morning, along with any pertinent case information, and leave everything there for a week. A skull, mandible, two thigh bones, and a section of pelvis might be piled on top of a tray along with the preliminary notes taken on the day the bones were found-for example, “Human skeletal remains found in a ditch along Alcoa Highway on July 7, 1987. No clothing was recovered.” Then we had to analyze the remains, explaining what they told us about the victim's age, race, sex, stature, and any other clues we could come up with.

There were only about fifteen students in our class, so we split into teams of three or four and took turns examining the bones during the week and in our Thursday class. By the following Tuesday, we were each expected to produce a report-just like the ones we might turn in to a police investigation-telling the investigators everything we'd gleaned from our anthropologic examination. In fact, the class was as much about preparing the report as it was about analyzing the remains-no forensic anthropologist will last very long if he or she can't document evidence and share information with investigators-and it was made crystal clear from the beginning that we were to choose our words carefully and back up our opinions with good, hard science.

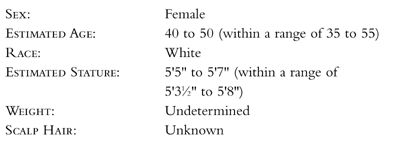

I was used to writing reports, of course, but only in the style of the medical records I had worked with at the clinic, in which a typical entry might state confidently, “This is a forty-five-year-old White female, 5'6'' tall weighing 145 pounds.” Of course, you could describe a whole body-living or dead-in that kind of detail. When all you've got is a skeleton, you can never be that specific, though you can usually come up with a more basic biological profile. For example:

BIOLOGICAL PROFILE: Case # 02-17

|

Every biological profile, Dr. Bass told us, would ideally include the anthropologist's “Big Four”: sex, age, race, and stature. If you're lucky, and you've got the evidence to go further, you can put in ancillary information such as weight and maybe hair color. Often, human remains

Sometimes the associated evidence-evidence found with a body or remains-can give you a clue. Clothing, for example, can help you determine a person's weight and size, though, of course, it too tends to decompose. In the end, though, the bones last longest-and they hold many secrets if you know what to look for.

|

One of the most basic ways we identify each other is by sex, so when I'm looking at newly discovered bones, I often start by asking myself whether they belonged to a man or a woman. Under these circumstances, I hope I've got at least part of the skull or the pelvis, because these bones possess the best morphological features to reveal the differences between male and female. (“Morphology” means the logic of shapes, the characteristics of a structure that can be seen but are difficult to measure.) Males, for instance, usually have a line of bone that juts out to form the “brow ridge,” a horizontal ridge between their forehead and the tops of their eye sockets. This ridge is smaller, or absent entirely, in females. Males also have distinctive areas-much bigger than women's-for their large muscles to attach behind each ear and in the back of the head, near the hairline.

But it's the pelvis that really tells you about someone's sex. The pelvis is made up of three separate bones. At the bottom of the spine sits the sacrum, a wide, thick bone, shaped like a slice of pie and full of holes. On either side sits the “innominate” or “no-name” bones, two relatively flat, softly curved slabs, each with a socket for one of the hip joints and a notch that allows the sciatic nerve to pass from the spine down into the leg. In females this sciatic notch begins to spread widely as a girl matures, while the front and back of a girl's pelvis becomes wider to accommodate the possible birth of a child. In men, the sciatic notch is narrower, as is the entire pelvis.

Overall, male skeletons tend to be larger and more robust than those of females, but there are exceptions to every rule. We've all met plenty of robust females and small, gracile males.

If sex is tricky to determine, age is really tough. After all, there are only two sexes-but a skeleton might be any age from 0 to 100. I personally have enough trouble telling the age of a living person, even when I can look at indicators like posture, hair color, and wrinkles.

Because exact age is so hard to figure, a forensic report usually gives age as an estimated range-say, thirty to forty in an adult; twelve to fifteen in a teenager or “subadult.” Subadults' ages are easier to estimate, since their bones and teeth mature at a pretty steady and well-documented rate for the first fifteen or sixteen years. Then their bones undergo changes that are a little less predictable as they enter their early twenties. The bones usually don't get any bigger after that, but they do continue to mature until the middle to late twenties.

Age-related changes continue until the day we die, showing up in our ribs, pelvis, and weight-bearing joints-knees, hips, ankles, and spine. The ends of our ribs are stressed every time we take a breath, while the bones of our pelvis grate together throughout our entire lives. The amount of movement is usually so minuscule that we don't even notice it-yet over time that movement is enough to wear down the underlying bone in ways that an anthropologist can use to read a person's age.

Likewise, although the joining, or articulating, bones in the ankles, knees, hips, and spine are covered with a generous cushion of cartilage, sooner or later the cartilage wears down, leaving a record of every day we've stood upright and all the thousands of miles we've walked. And as the cartilage wears down, like the rubber on a tire, the underlying bone begins to show changes: first some irregularities around the edge of the joint, then some roughening of the gliding surfaces. With extreme age-related changes, the whole joint can appear to bubble and boil with bony convolutions, and the weight-bearing surfaces might even collapse.

Age-related changes aren't limited to the legs or spine. The arms, hands, and shoulders are also susceptible to disease and can also show lifelong signs of wear and tear. And then there are the teeth: Are they rugged and unstained? Well worn? Missing, with subsequent absorption of bone?

You'd think estimating a person's stature, or height, would be easiest of all, and you'd be right-if you had a complete body or the right bones. If all you've got is, say, a rib, you're out of luck. Stature can best be calculated from the leg bones, though the arm bones come in a good close second. The length of any of these bones can be entered into a mathematical formula which can then be used to calculate the stature of an individual within a limited range.

Finally, we come to race, a subject that can quickly become touchy and politically charged. For forensic anthropologists, though, race is less of a political topic than a matter of procedure: What can we find out about a mass of bones or body parts that will help police figure out who the person was? In our society, people tend to identify themselves by race, and their friends, family, and coworkers usually know them that way, too. So Dr. Bass made sure we knew the latest thinking on how skeletal structure might vary, depending on a person's racial background.

The bones of a person's mid-face-eye sockets, cheeks, nose, and mouth-reveal our ethnic heritage. For example, Negroid heritage is displayed in a skull with a wide, flattened opening for the nose, wide-set eye sockets, and a forward projecting set of upper and lower jaws. Likewise, a long, narrow nose with a high-pitched nasal bridge and oval-shaped eye orbits tells me that the skull probably belonged to a Caucasian, while in someone of Asian parentage, I would expect to see relatively flat cheekbones and a nose whose characteristics fall somewhere between Negroids and Caucasians-neither flat nor high-bridged.

To learn all of this had taken us months-but by the time Dr. Bass threw his latest challenge at us, we'd all gotten pretty good and he knew it. Yet as he'd given us this week's collection of bones, his words had had the ring of triumph: “In twenty years, no one has ever gotten this one right.” Why not? It seemed to me that every one of us could have measured the bones on the tray, identified the morphological traits, and then told him that we were looking at a tall, well-muscled White man in his sixties. Why would such a simple problem have stumped students for the past two decades?

It was Friday night before I found my way back to the lab where Tyler and I worked together, measuring each bone and documenting our findings. We'd learned through the grapevine that our conclusions didn't differ from anyone else's. Yet I just couldn't shake the feeling that I was missing something.

The night before my report was due, I returned yet again to the lab. I ran my fingers over the contours of the bones and stared at them for hours in the semi-trancelike stillness that was often where I got my best ideas.

And then, suddenly, I

|

The next day, Dr. Bass collected our reports and began his usual oral questioning. “How many think this skeleton was male?”

Every hand in the room went up.

“Middle-aged?”

Unanimous again.

“About six feet tall, plus or minus an inch or two?”

Yes again.

“White?”

Every hand in the room rose-except mine.

“Miss Craig?” said Dr. Bass. He was always so courteous and formal, I couldn't tell whether he was surprised or not.

“I think the man was Black,” I said into the sudden silence.

Could it be that Dr. Bass was actually at a loss for words? For a moment, he just stared at me. Then he laughed, the way he usually did when one of us got it wrong, and my heart sank. Finally, he sighed.

“Well,” he said, drawing out his words for emphasis. “I never thought I'd see the day.” He shook his head and picked up a photo from his desk-a picture of the person whose bones these were. He was indeed male, middle-aged, tall-and Black. My classmates looked at each other and then at me.

Dr. Bass interrogated me further when we met in his office. “Miss Craig,” he asked me, “how did you know the man was Black?”

I tried to recall exactly what I had seen last night in the lab, which specific detail had triggered my flash of insight.

“It was his knees,” I said finally. “The joint just

Dr. Bass ran his hand across his buzz-cut, looking for all the world like the frazzled D.A. on

|

All right. How could I prove what I knew? Lucky for me, I found this an interesting problem, because it was a challenge that would recur again and again throughout my career: I'd have a flash of insight that would seem to descend mysteriously from nowhere, something I'd just

The general scientific basis for my discovery, of course, was something we'd all learned together in class. Once Dr. Bass had taught us the rules for determining race from bone, he'd gone on to explain that skeletal evidence doesn't always correlate with the color of a person's skin, or the texture of their hair, or even the continent they call home. The Caucasian bones in any given face might belong to a person of coffee-colored skin who identifies as Cuban or Latino or even African American. The owner of a skull with Negroid characteristics might have pale creamy skin and come from a family that considers itself Puerto Rican. Bones tell some of the story-but not all of it.

In this case, though, all I'd had to look at was the bones-and somehow I'd gotten it right. So what had tipped me off? The first clue I'd had to this man's race was when I'd looked at his femur, or thigh bone. Earlier that year, I'd learned that among Caucasoids-the scientific term for Whites-the femur demonstrates a forward bowing of the shaft, known to anthropologists as “anterior [forward] curvature.” In Black people-Negroids-the femur is relatively straight. The femur in Dr. Bass's assignment had been curved-and yet I had known the man was Black. How?

I decided to take a closer look at some femurs. Off I went to Bass's collection of bones, where I lined up twenty male right femurs-ten White males, ten Black-spacing them apart like railroad ties on the shiny black lab table. Slowly an idea began to grow. Maybe it wasn't the femur's shaft I'd been responding to, but the bone's distal end, the end that fits into the knee.

Was this one of those times when I had to rely on touch as well as sight? Closing my eyes, I ran my fingers slowly down to the notch at the distal end. First the White femurs. Then the Black ones…

Wait a minute-here was something! I opened my eyes. Now I could see it. The difference was in the intercondylar notch, the place at the center of the knee joint where the thigh fits into the knee. There was a marked racial difference in the angle of the notch-and somehow, without even realizing it, that was what I'd noticed.

By the time I was ready to graduate in the summer of 1994, I was able to prove that, on the average, the angle of the intercondylar notch differs by about 10 degrees between Blacks and Whites. And I'd come to understand why a generation of Dr. Bass's students had failed at the case I'd finally solved. Because of racial mixing in this country, many African Americans (and probably lots of Whites, too) have a variety of racial characteristics. Our test case's White heritage could be read in the bones of his skull and the curve of his thigh bones-clues to which we had all responded. But the angle of his intercondylar notch revealed his Black ancestry as well.

I was coming to see for myself that skin color doesn't necessarily line up with bone evidence. Our test case might have been light-skinned, dark-skinned, or anything in between, with bones that said one thing and hair and skin that hinted at another. This wasn't the last time I was almost fooled. In 1997, for instance, when I was working as the Commonwealth of Kentucky 's forensic anthropologist, I helped to recover a decomposed body from a cistern in Campbell County. Visually, it seemed that these remains had once belonged to a female with straight, reddish-brown hair and skin the color of dirty snow, so we gave local newspapers and TV stations a description of this missing White female, hoping that someone who knew her would come forward.

After weeks of no response, I agreed to do a three-dimensional facial reconstruction on this woman's skull-and as soon as I removed all of the flesh and saw her facial bones, I realized that our ID had gone awry. This woman's skull demonstrated evidence of racial admixture-that combination of White and Black parentage that leaves nature a lot of choices as to skin color, hair texture, and facial features. When we changed our description to “mixed race,” we were finally able to find someone who knew this person-a dark-skinned woman whose friends considered her “mixed race.” It seemed the six months she spent in the cistern had been enough to destroy her dark epidermal (outer) layer of skin, leaving only the pigment-free endodermal (inner) layer, a creamy white covering dotted with gray patches from the decomposition. Without the skeletal evidence, we would never have found out who she was.

|

Once we students had some training under our belts, we were sent out into the field as part of a forensic team that worked on actual Tennessee cases under Dr. Bass's supervision. This arrangement had been carefully worked out between the school and law enforcement agencies throughout the state, and it was an invaluable part of our training. Just as in class, all of our case findings had to be written in a concise report that could be read and understood by the wide range of local, state, and federal investigators who might be interested. We also knew that we might have to testify in court, explaining what we'd found in language that a jury could follow and defending our opinions against a defense attorney's challenges.

No longer were we doing this work for academic credit alone. Now it was for real, and the demands on us were high. We couldn't just state that a young woman had sustained a high-velocity gunshot wound to the side of her head-we had to describe the gross and microscopic appearance of the wound: How had her skull bone been damaged? At what point had the bullet entered? What did the hole look like? How did we know it was an entrance wound (where the bullet went in) and not an exit wound (where the bullet went out)? Then we had to back up our findings by citing documented studies of similar wounds.

Despite the simplified, positive statements that fictional detectives tend to make, we learned to pepper our reports with such cautious phrases as “most likely,” “consistent with,” and “appears to be.” And we made sure to back up every opinion we offered with citations from peer-reviewed scientific articles. Slowly but surely, we learned to avoid speculation about the actual murder scenario, limiting ourselves to strictly clinical terms and standard anatomical nomenclature. Let the TV scientists proclaim that

Although we were learning volumes from this on-the-job training, our professors warned us not to cut classes to work on a case. But by now we only had four or five hours of formal lectures each week, so we were usually able to respond quickly whenever we were called to a crime scene. Our team was loosely organized, drawn from a pool of about ten grad students, with a core group of half a dozen willing to be on call 24-7 to every law enforcement agency in the state of Tennessee.

Dr. Bass often went with us. But even when he wasn't physically present, we knew that the responsibility was ultimately his. As lead investigator, he would review everything we did and his signature would be above ours in every report. If we screwed up, you could bet we'd hear about it-but if we did well, we'd hear about that, too, and that was what kept us going. Once again, I had cause to be grateful for Dr. Bass's demanding standards, because it was this experience that really taught me how to think like a detective, how to use my common sense, instinct, and intuition as well as my book-learning.

Almost every case started with a visit to the crime scene. We never heard about the “fresh” bodies-that was a job for the pathologist. But if they found decomposing remains, unassociated body parts, or bones, they'd call in the anthropologists.

We'd rush to the scene-perhaps a farmhouse with two smoking corpses or maybe a back-alley apartment with a cache of bones hidden under the floorboards. We'd check in with the officer in charge, who would already have secured the scene. Then we'd work with the officers to come up with a plan for gathering and documenting the evidence.

Here is where I learned how crucial is the information gleaned from the scene. Sure, lab analysis was vitally important, but every investigation starts with the crime scene-if only you know how to look.

On one very early case, I, the novice, saw nothing out of the ordinary until fellow student Bill Grant pointed out that the charred body in the car was covered with burned maggots. This was irrefutable evidence that the man, and his car, had been torched well

In another case, the sheriff took me aside and told me that our murder suspect had just confessed to beating the victim to death with a golf club. I realized how close I might have come to disregarding the broken putter we'd just found in our search through a roadside dump for scattered bones.

Yet another time, I was initially led astray when I examined a severely decomposed and partially skeletonized body propped up against a tree with her legs splayed in a provocative pose-a location that could be easily seen from a nearby road. I assumed that the victim had died there-until I found another site, about fifteen feet away, that contained her teeth, a portion of her broken jaw, pieces of her jewelry, and a mat of her scalp hair, which had sloughed off during the early stages of decomposition. Clearly, someone had moved the dead girl and propped her up in a perverse attempt to display her to passersby. I figured this one out after about two hours of careful analysis, but next time I'd know not to make any quick assumptions about where and how someone had died until I had thoroughly investigated the entire crime scene.

Once we'd learned everything we could from the scene, we'd take the evidence back with us to the university lab, covering every piece of evidence with the paper trail known in law enforcement circles as the “chain of custody.” Whenever any piece of evidence changed hands, someone had to sign and date a piece of paper indicating who was taking it and where it was going.

Back at the lab, we'd begin the second phase of the analysis. Our job was most often to help the police identify victims, offering basic information that would enable police to request someone's medical records or talk to a family in search of a positive ID. Police also asked us to help determine time of death-pathologists could do that from intact soft tissue remaining on whole fresh corpses, but we anthropologists were becoming specialists in analyzing decaying flesh, charred tissue, and bone.

We were fortunate to have the decay facility as a reference resource. For example, say we had a case where skeletal remains were found still encased in a flannel shirt and denim jeans. We could turn to documentation from studies of corpses dressed in similar garments, learning how long it had taken for the clothes to rot away to the point where they matched the victim's. If we had a decomposing body, we could turn to Bass's notes on research projects documenting the rate and pattern of postmortem tooth loss; of maggot infestation; and of soft-tissue decomposition, liquefaction, and eventual disappearance.

Every day we were finding answers to new questions, and each answer led to still more questions: How long does it take for the plants surrounding a corpse to discolor, die, and then return with vigor? Do the bloodier corpses affect plants differently than the ones that are relatively intact? How long does it take for a person's hair to fall out-and under what kind of circumstances will it fall out faster? What if an animal uses this hair in its nest-how far away should you look for that and how do you recognize it? Does the hair change color after death? What if it's gotten contaminated with rotting flesh and animal feces-how can you tell and what should you look for? We learned to ask these and a thousand other questions-and, slowly but surely, we learned to answer them, answers that I put to good use working the rest of the cases in this book.

|

What brought it all together for me was what I like to think of as the “Friends and Family Case of 1993.” It all began when the Grainger County rescue squad pulled Richard Carpenter's relatively fresh body out of a cistern. No, amend that: They pulled out

The detectives were already putting a case together against Donald Ferguson, whose arrest warrant alleged that he had “slipped up behind” his longtime friend Richard and “hit him in the head with a hammer.” Donald then reportedly cut off Richard's head and penis with the electric carving knife that hung by the kitchen door in the tiny frame house that Donald shared with his mother. As reported in the

Nannie, who had suffered repeated psychological and physical abuse from her son, was severely beaten by him once more. Instead of cowering in submission as she had done so many times, she fled directly to the Grainger County Sheriff's Department and filed a complaint. “I've got bruises all over my body… and I've been wanting to talk about this,” she said. She also told authorities that Donald had put the body in the cistern.

County D.A. Al Schmutzer thought the murder had occurred on Thursday night, August 19. On Friday morning, when Grainger County deputies arrived at his house, Donald was, as always, out front with a broom, tidying things up. Richard Carpenter's truck was still in the driveway and his mixed-breed dog was still standing guard over it. The bewildered dog wandered off that afternoon, never to be seen again.

Later that day, volunteer members of the local fire and rescue squad pulled the body from the cistern, and Dr. Blake called us. He'd seen the cut marks on the victim's neck bones, and he expected to find matching cut marks on the vertebrae still attached to the head. He wanted anthropologists to document that these marks did indeed match and then to help him further match the cut marks to a specific knife or saw.

Just as my classmates Tom Bodkin, Lee Meadows-Jantz, and I pulled up in our big white truck, volunteers were lifting the plastic bag containing the victim's head out of the water with a grappling hook, while the deputies watched from the farmhouse's back door, smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee. We joined them, expecting to be steered toward the newly discovered head. But after we all exchanged the pleasantries that are a cultural requirement in the South, the deputies escorted us into the suspect's bedroom.

When they arrested Ferguson, they told us, they'd insisted that he empty his pockets and spread the contents on his bed. There among his keys and loose change was a human kneecap. This patella appeared to have acquired a smooth polish, the kind it might have gotten from the skin oils and regular rubbing of a human hand. And indeed, Ferguson told the deputies, he'd been carrying the patella in his pocket for the past year. Then he told us even more-he'd thrown his wife, Shirley, into the cistern after beating her to death two years earlier. He'd made up a story about her running off with another man and, until now, everyone had believed him.

By now Ferguson was at the local jail and was no longer cooperating with the authorities. So Tom, Lee, and I gathered in the yard with Dr. Blake, the men from the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation (TBI), the sheriff's department, and the local rescue workers.

“We already searched the yard and outbuildings when we were looking for Richard,” one burly deputy explained. He added that he and his colleagues had found tiny bits of blood spattered on the kitchen walls and floor despite the obvious lengths to which someone had gone to clean up the crime scene. So, he went on, investigators had kept searching until they found the patella in Ferguson 's pocket. Now, despite his confession, they needed us to confirm that the object was indeed a human bone. Yes, Lee told him. It was. Clearly there were more skeletal remains to be found, so we formed teams to look for them-one for the house, a second for the yard and outbuildings, and a third to drain the cistern.

Cisterns are an integral part of homes throughout Appalachia. The rural areas don't always have sewers or water services, and it's usually too expensive to sink a well. If someone living in the country wants water, he or she pretty much has to collect rainwater or bring in a truckload of water to fill the cistern-a large, concrete-lined hole or a polyvinylchloride (PVC) drum buried in the ground, about three feet wide at the top, six to eight feet wide at the bottom, and up to twelve feet deep.

Detectives hadn't yet had to enter Ferguson 's concrete cistern-they'd used ropes and grappling hooks to retrieve Carpenter's body and then his head. But if there were more bones down there, a grappling hook wouldn't be enough. As we made our plans, Dr. Blake let us see the head, which he'd already photographed. There, in the victim's mouth, was the bloody stump of an amputated penis. As we stood staring at it, the rescue workers continued to drag the cistern with a net, retrieving a few plastic bags, a rotting shirt, and a single bone, which one of the firefighters held high over his head and waved in the air. All of us anthropologists could see right away that it was a radius-a bone from the human forearm.

“Okay,” I heard myself saying. “Now we know Ferguson was telling the truth. We'll have to drain the cistern.” Much to my surprise, the words came out with a tone of authority that sounded confident even to me. I expected the other investigators to cock their heads and smirk at the “uppity new kid,” but they only nodded in agreement and asked my advice on how to retrieve the rest of the bones without damaging any critical evidence.

Suddenly, everyone was looking at me. Lee was actually the most experienced member of the team, with Tom still a newcomer. But by age, I appeared to be the senior member of our team, so folks seemed to assume that I'd be the one to come up with something.

I knew that someday I'd be out of school, and then I really would be in charge of recovery efforts like this one. I felt so ill-equipped-and I knew that the investigative team in Ferguson 's yard had decades of training and experience. Surely the local firefighters knew more about cisterns than I did. And clearly the detectives had amassed years of experience searching for and documenting evidence.

So I came up with an approach that I still rely on today: I gathered the leaders of each team and drew on their strengths. “All right, gentlemen,” I said to the sheriff's chief deputy, the lead man from TBI, the volunteer fire chief, and Dr. Blake, the M.E. “Let's work together to set up a plan. We need to get all the water out of that cistern, but we can't disturb or lose any evidence. What do

To my delight, this method worked. The team members immediately began offering suggestions-for my approval. For the first time I could remember, my relatively advanced age was working for me-at the ripe old age of forty-five, I at least

I started with the team that was going to drain the cistern. The local fire department had figured out how to pump the water out, so I made only one small suggestion: Put a screen over the outflow pipe to catch any small particles or bones that might be sucked out with the water. They improvised, pulling a screen from an outbuilding's window and propping it up on concrete blocks. A few minutes later, we found our first prize: some small human hand bones.

Lee was now busy over at a dump site at the property's edge, where she'd found what looked like another piece of bone in a pile of ashes. She'd found a chunk of parietal bone from the side of a skull-and to everyone's bewilderment, there seemed to be a neat round hole right in the middle of it. Detailed analysis of

Not yet, however, because just then, another detective who had been searching the kitchen called out to me. He had found still more bones-in the kitchen cupboard, propped up on a plastic canister beside a glass that held a toothbrush and a tube of toothpaste. At first he'd thought the items were soup bones, or maybe bones set aside for some dog-but I saw at a glance that he'd found two human heel bones and a piece of a breastbone, or sternum. Like the bone in the trash pile, the sternum had a neat round hole right through the middle. What in the hell was going on here?

No sooner had I identified these bones as being human than another firefighter came rushing in from draining the cistern.

“The water is almost all out, and you won't believe what we've got down there, Doc,” he cried out. “It looks like almost a whole skeleton!”

The discovery didn't surprise me-but being called “Doc” did. I'm sure it happened just because the volunteer didn't know my name. But even though I didn't yet have a right to the title, I didn't correct him. After all, I didn't want to embarrass him, did I?

From that point on, things kept happening faster and faster. When I looked down into the cistern, I saw dozens of human bones, all jumbled up on the bottom. If they had seemed to mirror the victim's position at death-stretched out prone, huddled against a wall, or bound hand and foot-we would have had to document their position. Since they were so clearly in disarray, though, we decided simply to send someone down into the cistern to retrieve them. (Later I wondered what the murderer and his mother did about their drinking water. Maybe they thought the bones gave it an interesting flavor. At any rate, the decomposing body didn't seem to have affected their health-or not so they noticed.)

Of course, getting into the cistern was harder than it sounded. Whoever went down there would be working in a confined underground space where a body had been rotting, producing gases and other toxins. The fire chief insisted that anyone who entered the cistern had to wear a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) tank and respirator, adding to the sense of danger. Finally, Tom agreed to take on the job.

Meanwhile, Lee and I had other work to do. Searchers were finding bones all over the property, and we were being called over to inspect their findings in the yard, behind the barn, in and under the outbuildings. Luckily all of these new discoveries turned out to be animal bones-some from table scraps fed to the dogs, some from rabbits, rats, opossums, and cats that had apparently died some time ago. However, there were still plenty of human bones in the cistern, the stove, and the cupboard.

Eventually, it grew dark, so we secured the scene for the night, stringing crime scene tape around the property and putting a sheriff's deputy on guard to keep civilians out. But the next morning, as we pulled onto the small road that led up to the Ferguson farm, we found it jammed with the cars and pickup trucks of local residents. Word about the murders had traveled quickly and our crime scene had turned into a Saturday-morning picnic, with residents setting up their lawn chairs, opening up their picnic baskets, and playing with their children.

“I don't believe it,” I said under my breath to Lee. But she had grown up in this area and she just shook her head.

“Around here, that's par for the course,” she drawled. “Can't say as I blame them. It's cheaper than a movie.”

So for the rest of the day, we had an audience. They called out encouragement to us when we started sifting an area that Ferguson had used as a dump, and they let out a loud cheer when detectives dismantled the wood-burning stove and brought it out into the yard so that Lee and I could sift the ashes. Lee was about seven months pregnant at the time, and as she bent over the sifting screen, one of the onlookers called out an offer of his folding lawn chair.

“Why not?” Lee called back. “Thanks!” When I offered to walk over and get the chair, a little girl came running over with a chair for me, too. Lee and I went back to work, sifting ashes in relative comfort while the crowd ate their picnic lunches and country music blared from the radio on a nearby pickup.

Later that day, deputies brought Ferguson to the scene and began questioning him about where he'd put the rest of his wife's remains. So far, we'd found her bones mixed in with his pocket change, in the cistern, in the kitchen cupboard, in the stove, and in a trash dump. But some bones were still missing, and the deputy suggested that I question him myself.

I had never knowingly spoken to a murder suspect before, but I was willing to give it a try. I don't know what I expected, but in a million years, I'd never have guessed what Ferguson said when I asked him where the bones were.

“Oh,” he said calmly, “I pulled them out of the cistern and burned them for fuel this winter. It got pretty cold out here.” Amazingly, he knew the name of every bone and gave me a detailed description of which ones he'd hidden in the kitchen, as opposed to those he'd put in his bedroom. Not only that, but he cleared up the mystery of the holes. In apparent fits of loneliness, he would retrieve one of his wife's bones from the cistern and drill a hole in it just big enough to thread with a long leather thong. Then he'd wear it around his neck, giving a whole new meaning to the term “trophy wife.”

Ferguson also assured us that we had scoured all of his hiding places (and he eventually pled guilty to both murders). We had enough evidence to convict him and enough bones to identify the victim, so detectives from the TBI told us to go home.

As Lee and I packed up our gear and made our way back to our truck, the crowd of onlookers started to applaud. To them, we weren't just dirty, tired forensic anthropology students. We were some kind of heroes.

Lee and I looked at each other and laughed. At this point I wasn't worried about an inappropriate reaction. What

But I'd turned over an important page in my professional development there in Bean Station, Tennessee. For the first time, I'd been considered the lead investigator on the forensic anthropology team. Experienced investigators had turned to me for direction and I was forced to make quick decisions that-right or wrong-would affect the investigation's outcome. I felt that I had passed a final, crucial test-a test that I now realized I'd be taking over and over and over again. There would never be a rule book at any crime scene I processed. I'd have to rely on common sense, academic training, and the ability to improvise-just as I had done here.

But next time I'd bring my own lawn chair.

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |