"Icehenge" - читать интересную книгу автора (Robinson Kim Stanley)

Part Three EDMOND DOYA 2610 A.D.

SOMETIMES I dreamed about Icehenge, and walked in awe across the old crater bed, among those tall white towers. Quite often in the dreams I had become a crew member of the

“I’m landing at the geographical pole — you’d better send a party up here fast… there’s a… a

Then I would dream I was in the LV that sped north to the pole, crowded in with Ehrung and the other officers, sharing in the tense silence. Underneath us the surface of Pluto flashed by, black and obscure, ringed by crater upon crater. I remember thinking in the dreams that the constant radio hiss was the sound of the planet. Then — just like in the films the

Then we were all outside, in suits, stumbling toward the structure. The sun was a bright dot just above the towers, casting a clear pale light over the plain. Shadows of the towers stretched over the ground we crossed; members of the group stepped into the shadow of a beam, disappeared, reappeared in the next slot of sunlight. The regolith we walked over was a dusty black gravel. Everyone left big footprints.

We walked between two of the beams — they dwarfed us — and were in the huge irregular circle that the beams made. It looked as if there were a hundred of them, each a different size. “Ice,” said a voice on the intercom. “They look like ice.” No one replied. And here the dreams would always become confused. Everything happened out of order, or more or less at once; voices chattered in the earphones, and my vision bumped and jiggled, just as the film from that first hand-held camera had done. They found poor Seth Cereson, who had pressed himself against one of the largest beams, faceplate directly on the ice, in a shadow so that he was barely visible. He was in shock as they led him back to the LVs, and kept repeating in a small voice that there was something moving inside the beam. That frightened everyone a bit. Several people walked over and inspected a fallen beam, which had shattered into hundreds of pieces when it hit the ground. Others looked at the edges of the three triangular towers, which were nearly transparent. From a vantage point on top of one of the beams I looked down and saw the tiny silver figures scurrying from beam to beam, standing in the center of the circle looking about, clambering onto the fallen one…

Then there was a shout that cut through the other voices. “Look here! Look here!”

“Quietly, quietly,” said Ehrung. “Who’s speaking?”

“Over here.” One of the figures waved his arms and pointed at the beam before him. Ehrung walked swiftly toward him, and the rest of us followed. We grouped behind her and stared up at the tower of ice. In the smooth, slightly translucent white surface there were marks engraved:

|

For a long time Ehrung stood and stared at them, and the crew behind her stared too. And in the dream, I knew that they were two Sanskrit words, carved in the Narangi alphabet:

Another time, caught in that half sleep just before waking, when you know you want to get up but something keeps you from it, I dreamed I was on another expedition to Icehenge, a later one determined to clear up once and for all the controversy surrounding its origins. And then I woke up. Usually it is one of the few moments of grace in our lives, to wake up apprehensive or depressed about something, and then realize that the something was part of a dream, and nothing to worry about. But not this time. The dream was true. The year was 2610, and we were on our way to Pluto.

There were seventy-nine people on board

My refrigerator was empty, so after I splashed water on my face, I went out into the corridor, it had rough wood walls, set at slightly irregular angles; the floor was a lumpy moss that did surprisingly well underfoot.

As I passed by Jones’s chamber the door opened and Jones walked out. “Doya!” he said, looking down at me. “You’re out! I’ve missed you in the lounge.”

“Yes,” I said, “I’ve been working too much, I’m ready for a party.”

“I understand Dr. Brinston wants to talk to you,” he said, brushing down his tangled auburn hair with his fingers. “You going to breakfast?”

I nodded and we started down the corridor together. “Why does Brinston want to talk to me?”

“He wants to organize a series of colloquia on Icehenge, one given by each of us.”

“Oh, man. And he wants me to join it?” Brinston was the chief archaeologist, and as such probably the most important member of our expedition, even though Dr. Lhotse of the Institute was our nominal leader. It was a fact Brinston was all too aware of. He was a pain in the ass — a gregarious Terran (if that isn’t being redundant), and an overbearing academic hack. Although not truly a hack — he did good work.

We turned a corner, onto the main passageway to the dining commons. Jones was grinning at me. “Apparently he believes that it would be essential to have your participation in the series, you know, given your historical importance and all.”

“Give me a break.”

In the white hallway just outside the commons there was a large blue bulletin screen in one of the walls. We stopped before it. There was a console under it for typing messages onto the board. The new question, put up just recently, was the big one, the one that was sending us out here: “Who put up Icehenge?” in bold orange letters.

But the answers, naturally, were jokes. In red script near the center of the board, was “GOD.” In yellow type, “Remnants of a Crystallized Ice Meteorite.” In a corner, in long green letters: “Nederland.” Under that someone had typed, “No, Some Other Alien.” I laughed at that. There were several more solutions (I liked especially “Pluto Is a Message Planet From Another Galaxy”), most of which had first been put forth in the year after the discovery, before Nederland published the results of his work on Mars.

Jones stepped up to the console. “Here’s my new one,” he said. “Let’s see, yellow Gothic should be right: ‘Icehenge put there by prehistoric civilization’ ” — this was Jones’s basic contention, that humans were of extraterrestrial origin, and had had a space technology in their earliest days — “’But the inscription carved on it by the Davydov starship.’”

“Jones,” I scolded him. “You’re at it again. How many of these solutions have you put up?”

“No more than half,” he said, and seeing my expression of dismay he cackled. He made me laugh too, but we straightened up and put on serious frowns before we entered the dining commons.

Inside, Bachan Nimit and his micrometeorite people were seated at a table together, eating with Dr. Brinston. I cringed when I saw him, and went to the kitchen.

Jones and I sat at a table on the other side of the room and began to eat. Jones, system- famous heretic scholar of evolution and prehistory, had nothing but a pile of apples on his plate. He adhered to the dietary laws of his home, the asteroid Icarus, which decreed that nothing eaten should be the result of the death of any living system. Jones’s particular affinity was for apples, and he finished them off rapidly.

I was nearly done with my omelet when Brinston approached our table. “Mr. Doya, it’s good to see you out of your cabin!” he said loudly. “You shouldn’t be such a hermit!”

Now I left my cabin pretty regularly to party, but when I did I was careful to avoid Brinston. Here I was reminded why. “I’m working,” I said.

“Oh, I see.” He smiled. “I hope that won’t keep you from joining our little lecture series.”

“Your what?”

“We’re organizing a series of talks, and hope everyone will give one.” The micrometeor crew had turned to watch us.

“Everyone?”

“Well — everyone who represents a different aspect of the problem.”

“What’s the point?”

“What?”

“What’s the point?” I repeated. “Everyone on board this ship already knows what everyone else has written and said about Icehenge.”

“But in a colloquium we could discuss these opinions.”

The academic mind. “In a colloquium there would be nothing but a lot of arguing and bitching and rehashing the same old points. We’ve wrangled for years without anyone changing his mind, and now we’re going to Pluto to look at Icehenge and find out who really put it there. Why stage a reiteration of what we’ve already said?”

Brinston was flushing red. “We hoped there would be new things to be said.”

I shrugged. “Maybe so. Look, just go ahead and have your talks without me.”

Brinston paused. “That wouldn’t be so bad,” he said reflectively, “if Nederland were here. But now the two principal theorists will be missing.”

I felt my distaste for him turn to dislike. He knew of the relationship between Nederland and me, and this was a jab. “Yes, well, Nederland’s been there before.” He had, too, and it was too bad he hadn’t made better use of the visit. They had done nothing but dedicate a plaque commemorating the expedition of asteroid miners that he had discovered; at the time, his explanation was so widely believed that the megalith hadn’t even been excavated.

“Even so, you’d think he’d want to be along on the expedition that will either confirm or contradict his theory.” His voice grew louder as he sensed my discomfort. “Tell me, Mr. Doya, what did Professor Nederland say was his reason for not joining us?”

I stared at him for a long time. “He was afraid there would be too many colloquia,” I said, and stood up. “Now excuse me while I return to my work.” I went to the kitchen and got some supplies, and walked back to my room, feeling that I had made an enemy, but not caring much.

Yes, Hjalmar Nederland, the famous historian of Icehenge, was my great-grandfather. It was a fact I remember always knowing, though my father never encouraged my pleasure in knowing it. (Father wasn’t his grandchild; my mother was.)

I had read all of Nederland’s books — the works on Icehenge, the five-volume Martian history, the earlier books on terran archaeology — by the time I was ten. At that time Father and I lived on Ganymede. Father had gotten lucky and was crewing on a sunsailer entered in the InandOut, a race that takes the sailers into the top layer of Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Usually he wasn’t that lucky. Sunsailing was for the rich, and they didn’t need crews often. So most of the time Father was a laborer: street sweeper, carrier at construction sites, whatever was on the list at the laborer’s guild. As I understood later, he was poor, and shiftless, and played the edges to get by. Maybe I’ve modelled my life on his.

He was a small man, my father, short and spare-framed; he dressed in worker’s clothes, and had a droopy moustache, and grinned a lot. People were always surprised to see him with a kid — he didn’t look important enough. But when he lived on Mars, and then Phobos, he had been part of a foursome. The other man was a well-known sculptor, with a lot of pull in artistic circles. And my mom, being Nederland’s granddaughter, had connections with the University of Mars. Between them they managed to get that rare thing (especially on Mars), the permission to have a child. Then when the foursome broke up, Father was the only one interested in taking care of me; he had grown up with me, in a sense, in that my presence as an infant was what brought him out of a funk. So he told me. Into his custody I went (I was six, and had never set foot on Mars), and we took off for Jupiter.

After that Father never discussed my mother, or the other members of the foursome, or my famous great-grandfather (when he could keep me from bringing up the topic), or even Mars. He was, among other things, a sensitive man — a poet who wrote poems for himself, and never paid a fee to put them in the general file. He loved landscapes and skyscapes, and after we moved to Ganymede we spent a lot of time hiking in suits over Ganymede’s stark hills, to watch Jupiter or one of the other moons rise, or to watch a sunrise, still the brightest dawn of them all. We were a comfortable pair. Ours was a quiet pastime, and the source of most of Father’s poetry. The poems of his that exerted the most pull on me, however, were those about Mars. Like this one:

Even though Father disliked Nederland (they had met, I gathered, only once) he still indulged my fascination with Icehenge. For some reason I loved that megalith; it was the greatest story I knew. On my eleventh birthday Father took me down to the local post office (at this time we were on bright Europa, and took long hikes together across its snowy plains). After a whispered conference with one of the attendants, we went into a holo room. He wouldn’t tell me what we were going to see, and I was frightened, thinking it might be my mother.

The room holo came on, and we were in darkness. Stars overhead. Suddenly a very bright one flared, defining a horizon, and pale light flooded over what now appeared as a dark, rocky plain.

Then I saw it off in the distance: the megalith. The sun (I recognized it now, the bright star that had risen) had only struck the top of the liths, and they gleamed white. Below the sunlight they were square black cutouts, blocking stars. The line quickly dropped (the holo was speeded up) and it stood revealed, tall and white. Because of the model of it that I owned at the time, it seemed immense.

“Oh,

“Bring it here, you mean.”

He laughed, “Where’s your imagination, kid?” He dialed it over — I went straight through a lith — and we were standing at its center, near the plaque commemorating the Davydov Expedition. We circled slowly, necks craned back to look up. We inspected the broken column and its scattered pieces, then looked closely at the brief inscription.

“It’s a wonder they didn’t all sign their names,” said Father.

Then the whole scene disappeared and we were standing in the bare holo room. Father caught my forlorn expression, and laughed. “You’ll see it again before you’re through. Come on, let’s go get some ice cream.”

Soon after that, when I was just fourteen, he got a chance to go to Terra. Friends of his were buying and taking a small boat all the way back, and they needed one more crew member. Or perhaps they didn’t absolutely need one, but they wanted him to come.

At that time we had just moved back to Ganymede, and I had a job at the atmosphere station. We had lived there nearly a year, off and on, and I didn’t want to move again. I had written a book describing the deep space adventures of the Davydov expedition, and with the money I was saving I planned to publish it. (For a fee anyone can put their work in the data banks, and have it listed in the general catalogue; whether anyone will ever read it is another matter, but I had hopes, at the time, that one of the book clubs would buy the rights to list it in their index.)

“See, Dad, you’ve lived on Terra and Mars, so you want to go back there so you can be outside and all. Me, I don’t care about that stuff. I’d rather stay here.”

Father stared at me carefully, suspicious of such a sentiment, as well he might be — for as I understood much later, my disinclination to go to Terra stemmed mainly from the fact that Hjalmar Nederland had said in an interview (and implied in many articles) that he didn’t like it.

“You’ve never been there,” my father said, “else you might not say that. And it’s something you should see, take my word for it. The chance doesn’t come that often.”

“I know, Dad. But the chance has come for you, not me.”

He scowled at me. In a world with so few children, everyone is treated as an adult; and my father had always treated me as an equal, to a degree that would be difficult to describe. Now he didn’t know what to say to me. “There’s room for you too.”

“But only if you make it. Look, you’ll be back out here sailing in a couple of years. And I’ll get down there someday. Meanwhile I want to stay here. I got a job and friends.”

“Okay,” he said, and looked away. “You’re your own man, you do what you want.”

I felt bad then, but not nearly so much as I did later, when I remembered the scene and understood what I had done. Father was tired, he was going through a hard time, he needed his friends. He was about seventy then, and he had nothing to show for his efforts, and he was tired. In the old days he’d have been near the end, and I suppose he felt that way — he hadn’t yet gotten that second wind that comes when you realize that, far from being over, the story has just begun. But that second wind didn’t come from me, or with my help. And yet that, it seems to me, is what sons are for.

So he left for Terra, and I was on my own. About two years later I got a letter from him. He was in Micronesia, on an island in the Pacific Ocean somewhere. He had met some Marquesan sailors. There were fleets of the old Micronesian sailing ships, called

And that’s what he has been doing, from that day to this: forty-five years. Forty-five years of learning to gauge how fast the ship is moving by watching coconuts pass by; memorizing the distances between islands; reading the stars, and the weather; lying at the bottom of the ship during cloudy nights, and feeling the pattern of the swells to determine the ship’s direction… I think back to the hand to mouth times of our brief partnership, and I see that he has, perhaps, found what he wants to do. Occasionally I get a note from Fiji, Samoa, Oahu. Once I got one from Easter Island, with a picture of one of the statues included. The note said, “And this one’s not a fake!”

That’s the only clue I’ve gotten that he knows what I’m doing.

So I stayed on Ganymede and lived in dormitories, and worked at the atmosphere station. My way of life had been learned in the years with my father; it was all I knew, and I kept to the pattern. Dorm mates were my family, and that was never a problem. After my name came up on the hitchhiker’s list I moved out to Titan, and while waiting for a job with the weather company I joined the laborer’s guild, and swept streets, and pushed wheelbarrows, and unloaded spaceships. I liked the work, and quickly became quite strong.

I got a room in a boarding house that had advertised at the guild, and found that most of my housemates were also laborers. It was a congenial crowd: the meals were rowdy affairs, and the parties sometimes lasted through the night — our landlady loved them. One of the older boarders, a woman named Angela, liked to argue philosophy — to “discuss ideas,” as she called it. On cold nights she would call a few of us on the intercom and invite us down to the kitchen, where she would brew endless pots of tea, and badger me and three or four other regulars with questions and provocations. “Don’t you think it is well established that all of the assassinated American presidents were killed by the Rosicrucians?” she would demand, and then tell us how John Wilkes Booth had escaped the burning barn to live on, take on another identity, and shoot both Garfield and McKinley…

“And Kennedy too?” John Ashley asked. “Are you sure this isn’t Ahasuerus the Assassin you’re discussing here?” John was a Rosicrucian, you see, and was naturally incensed.

“Ahasuerus?” Angela inquired.

“The Wandering Jew.”

“Did you know that originally he wasn’t a Jew at all?” George asked. “His name was Cartaphilus, and he was Pontius Pilate’s janitor.”

“Wait a second,” I said. “Let’s get back to the point. Booth was identified by his dental records, so the body they found in the barn was definitely his. Dental records are pretty conclusive. So your whole idea falls apart right at the start, Angela.”

She would contest it every time, and we would move on to the nature of evidence, and then the nature of reality, while pot after pot of tea was brewed and consumed. I would argue Aristotle against Plato, Hume against Berkeley, Peirce against the metaphysicals, Allenton against Dolpa, and the warm kitchen echoed with our fierce talk. Many was the time when I vanquished the rest with my mishmash of empiricism, pragmatism, logical positivism, and essentialist humanism — or I thought I did, until late in the night when I went up to my tiny book-walled room on the fourth floor, and lay on my bed and stared at the books and wondered what it was all about. Could it really be true that all we knew was what our senses told us?

Once John Ashley brought down to our kitchen group a volume called

“Yes, but look at all he says about how

“No no no, none of those are serious dating methods. Calculating the chances of a lith getting hit by a meteorite? Why, it doesn’t matter

And John would argue right back that it wasn’t, and Angela and George and the others would usually support him. “How can you be so sure, Edmond? How can you be

Not that I was always so positive in my feelings toward my great-grandfather. Once I was walking home after a hard day of loading pipe. I had had some beers after work with the rest of the loading gang, and I was feeling low. Passing a holo sales shop I noticed a panel discussion in the window holo and stopped to watch, recognizing one of the doll- like figures to be Nederland. Curiously I contemplated him. He was discussing something or other — on the street it was hard to hear the store’s speaker — with a group of well- dressed professor types, who looked much like him; he was authoritative, impeccably groomed, and on his tiny face was an expert’s frown — he was getting ready to correct the speaker,

I remembered that once I had badgered my father: “Why don’t you like you like Great- grandpa, Dad? Why? He’s famous!” It took a lot of that to get Father even to admit he disliked Nederland, much less explain it. Finally he had said, “Well, I only met him once, but he was rude to your mother. She said it was because we had bothered him, but I still thought he could have been polite. She was his own granddaughter, and he acted like she was some beggar dunning for change. I didn’t like that.”

I left the holo shop window and continued home thinking about it, and when I came to my shabby old boarding house, and looked at its stained walls and etched windows, and remembered the sight of Nederland on that expensive Martian stage in his fine clothes, I felt a little bitter.

But most of the time I was pleased to have such a historian for an ancestor; I was fascinated by his work, and made myself an expert in it. One wall of my book-lined room was covered with shelves of books by Nederland, or about Nederland, or about Oleg Davydov and Emma Weil, and the Mars Starship Association, and the Martian Civil War, and the rest of early Martian history. I became a scholar of that whole era, and my first publications were letters of comment in

So years passed, and Icehenge, and Nederland’s explanation for it, the astonishing story of the Davydov mutiny, remained a central part of my life. The turning point in my history — the end of my innocence, so to speak — came on New Year’s Eve, when the year 2589 became 2590. By that time I was working for the Titan Weather Company. Early in the evening I was on the job, helping to create a lightning storm that crackled and boomed over the raucous new town of Simonides. Just after the big blast at midnight — two huge balls of St. Elmo’s fire, colliding just above the dome — we were let off, and we hit town ready for a good time. The whole crew, all sixteen of us, went first to our regular bar, Jacque’s. Jacque was dressed up as the Old Year, and his pet chimpanzee was in diapers and ribbons, representing the New. I drank several beers and allowed a variety of capsules to be popped under my nose, and soon like most of the people there I was very drunk. My boss, Mark Starr, was rolling on the floor, wrestling the chimp. It looked like he was losing. An impromptu chorus was bellowing out an old standard, “I Met Her in a Phobos Restaurant,” and inspired by the mentioning of my native satellite, I started singing a complicated harmony part. Apparently I was the only one who perceived its beauties. There were shouts of protest, and the woman seated next to me objected by pushing me off the bench. As I recovered my footing she stood up, and I shoved her into the table behind us. People there were upset by her arrival and began pounding on her. Feeling magnanimous, I grabbed her arm and pulled her away. The moment she was clear of them she punched me hard in the shoulder, and swung again angrily. I parried the blow with a forearm and jabbed her on the sternum, but she had a longer reach and was much angrier, and I had to retreat quickly, warding off her blows. Despite a couple of good jabs I saw that I was outmatched, and I slipped through the throng at the bar and escaped out the door and into the street.

I sat down at the curb and relaxed. I felt good. There were lots of people on the street, many of them quite drunk. One of them failed to notice me, and tripped over my legs. “Hey!” he shouted, kneeling before me and grabbing my collar. “What d’you mean tripping me like that?” He was a big barrel-chested man, with thin arms that nevertheless were very strong; he shook me a little and it seemed to me his biceps looked like wire under the skin. He had long tangled hair, a small head, and he reeked of whiskey.

“Sorry,” I said, and tried to knock his hands away from my collar. I failed. “I was just sitting here when you ran over me.”

“Sure!” he shouted, and shook me again. Then he let go of me, and his eyes rolled a little; he crumpled back onto his butt, took stock of his situation dizzily, and slid himself over so that he was seated in the trash in the gutter, out of people’s way. I shifted away from him a foot or two, and he waved at me to stop. He took a vial from his shirt pocket, opened it with awkward care, waved it under his nose.

“You shouldn’t use that stuff,” I advised him.

“And why not?”

“It’ll give you high blood pressure.”

He peered up at me with bloodshot eyes. “High blood pressure is better than no blood pressure at all.”

“There is that.”

“So you’d better try some of this, hadn’t you.”

I didn’t know if he was serious or not, but I decided not to test it. “I guess I’d better.”

Slowly he levered himself up onto the curb next to me. Seated he looked like a spider. “You got to have blood pressure, that’s my motto,” he said.

“I see.”

He waved the vial under my nose, and immediately I felt the rush of the flyer. He left it there until I almost fainted with euphoria and lack of oxygen. “Man,” he said, “on New Year’s Eve everybody just goes

Then Mark and Ivinny and several more of the weather crew crashed out of Jacque’s. “Come on, Edmond, the chimp has got hold of a fire extinguisher and any minute it’ll be blasting us.”

I stood up, much too quickly, and when the colored lights went away I motioned to my new companion. He started to stand, we helped him the rest of the way. He stood a score of centimeters taller than the rest of us. We trailed my group of friends, talking continuously and barely listening to each other, we were so high. Then a forty-person free-for-all swirled out of a side street and caught us up in it; Simonides was filled with Caroline Holmes’s shipworkers, and it was nearing dawn, and from the roar bouncing down on us from the dome it appeared that there were brawls going on all over town. My new companion’s arms were only thin in relation to his giant torso, and with their length and power he was able to clear an area around him. I stayed close on his heels, and was hit on the side of the head by his elbow. When I regained consciousness a few seconds later he was dragging me by the heels after Mark and the rest. “What are you doing attacking me from behind, eh?” he shouted. “Don’t you know that’s dangerous?”

“Uh.” A vial shoved up one of my nostrils and I was clearheaded again. I staggered free of my companion and followed him and the weather crew through the clogged streets.

At dawn we were on the east edge of town, sitting on the wide concrete strip just inside the dome. There were seven or eight of the weather crew left, laughing and drinking from a tall white bottle. My new friend arranged pieces of gravel into patterns on the concrete. On the horizon a white point appeared, and lengthened into a knife-edge line dividing the night: the rings. Saturn would soon be rising.

My friend had grown a little melancholy. “Sports,” he scoffed in reply to a comment I had made on the night’s brawling. “Sports, it’s always the same story. The wise old man or men against the young turk or turks, and the young turk, if he’s worth his salt which he is by definition, always seems to win it, every time. Even in chess. You heard of that guy Goodman. Guy studies chess religiously for a mere twenty-five years, comes out at age thirty-five and wins three hundred and sixty tournament games in a row, trounces five- hundred-and-fifteen-year-old Gunnar Knorrson twelve-four-two, Knorrson who held the system championship for a hundred and sixty-some years! It’s damn depressing.”

“You play chess.”

“Yeah. And I’m five hundred and fifteen years old.”

“Wow, that’s old. You’re not Knorrson?”

“No, just old.”

“I’ll say.”

“Yes, I’ve seen a lot of these New Year’s Eves. I can’t say I remember very many of them…”

“Long time.”

“Yeah. Besides I doubt I’ll even remember this one tomorrow, so you can see how they might slip away.”

“You must have seen a lot of changes.”

“Oh yeah. Not as many, though, these last couple of centuries. It appears to me things don’t change as fast as they used to. Not as fast as in the twentieth, twenty-first, twenty- second, you know. Inertia, I guess.”

“Slower turnover in the population, you mean.”

“Yeah, that’s right. Everyone takes their time. I suppose it’s a commonly observed phenomenon.”

“Is it?”

“I don’t know. But damn it, why doesn’t the wise old man beat the young turk? Why don’t you keep getting better? Where does your creativity go?”

“Same place as memory,” I said.

“I guess. Well, what the hell. Winning ain’t essential. I’m doing fine without it. I wouldn’t have it over.” He shook his head. “Wouldn’t do like those Phoenixes. You heard of them? Folks banded together way back when in a secret society, and now they’re knocking themselves off on their five-hundredth birthdays?”

I nodded. “The Phoenix Club.”

“Phoenixes. Can you believe such stupidity? I never will understand those folks. Never understand those daredevils, either. Seems like the more you have to lose the bigger thrill you get from risking your life for no reason. Those damn fools dueling with sharp blades, trying to stand on Jupiter, having picnics on some iceberg in the rings — get themselves killed!”

“You really think people have more to lose by dying now than they did when they lived their three score and ten?”

“Sure.”

“I don’t.”

He shoved me onto my side, roughly. “You’re just a kid, you don’t know anything. You don’t know how strange it’s going to get.” Angrily he swept his pattern of gravel aside. “There’s only a couple hundred people in the whole system older than me. And they’re dying off fast. One of these days I’ll go too. My body’ll toss off all this medical manipulation and

“You done everything you wanted to?”

He shook his head, irritated with me.

“Me neither.”

He laughed scornfully. “I should hope not.”

I was still drunk; my head throbbed, and my whole life seemed to swirl before me, over the concrete outside the dome. “I’d like to see Icehenge.”

He jerked around, stared at me with an odd look in his eye. He pulled tangled hair back to see me better. “You’d like to see

“Ha!” he cried. Several sharp laughs exploded from him. “Ha! Ha! Ha!” He rolled to his knees, got to his feet. “Davydov, you say!”

“He headed the expedition that put the monument there.”

In his agitation he circled me, and again sharp barks burst from him. He stood before me, leaned down to hold a tightly bunched fist before my face. “He — did —

“What makes you think this Davydov had anything to do with it?”

“Um.” I gathered my thoughts. “A historian named Nederland tracked down the story on Mars, he found this journal—”

“Well he was wrong!”

I was taken aback. “I don’t think so, I mean, he has it all well documented—”

“Idiot! He does not. What does he say — some asteroid miners put together a half- baked starship and take off, what’s that got to do with Pluto? Think about that for a while.” He stalked over to the dome, slapped it hard with an open palm.

I stood up and followed him, confused but instinctively curious. “But they were the only ones out there, see — process of elimination—”

“No!” He almost spoke — hesitated — turned on his heel and walked away from me. I followed him, and when he stopped I circled him. His hands were clenched tightly before him.

“What’s wrong?” I said. “Why are you so sure Davydov’s expedition didn’t—”

And he swung around, grabbed me by the upper arm and yanked me toward him. “Because I know,” he said, voice thick. “I know who put it there.”

He let go of me, took a deep breath. At that moment Saturn broke over the horizon, and everyone on the dome strip started to cheer. All over Simonides voices and sirens and whistles and horns and bells marked the dawn of the new year with their ragged chorus. My companion tilted his head back and hooted harshly, then began to move through the crowd away from me.

“Wait!” I cried, and struggled after him. “Wait! Hey!” I caught up with him, grabbed his sleeve, pulled him around. “What do you mean? Who put it there? How do you know?”

“I

Not that that satisfied me. “How?” I asked.

He must have read my lips. He pointed a gnarled forefinger at his own face. “I helped build it! Ha!” In all the noise it was hard to hear him, and he seemed in part to be talking only to himself, which made it even harder to hear him, but he said something like, “I helped build it, and now I’m the last one. She only” — the blast of a horn — “old men and women out there, and now they’re all dead but me!” He said more, but the shouting crowd drowned his words.

“But who, why?” I shouted. “Wh—”

He cut me off with a jab in the sternum. “You find that. I give you that.” He turned and shoved his way toward the streets again, leaving people angry enough to make it hard for me to follow. I slipped around groups and barged through others, however, desperate to catch him. I saw his wild tangle of hair beyond a small knot of people, and I crashed through them — “Wait!” I shouted. “Wait!”

He heard me, and turned and charged me, knocking me down with a hard shove. I scrambled up swiftly, and saw his head sticking above the crowd, but as I hurried after him my pace slowed: what was the use? If he didn’t want to talk I couldn’t force anything from him.

So I stopped chasing him, and stood there in smoggy dawn sunlight completely disoriented, as if this new year had brought with it a new world. Around me strangers stared, pointed me out to others. I realized that I was filthy, disheveled — not that that made me stand out particularly in that crowd, but I was suddenly conscious of myself as I had not been for several minutes, at least. I shook my head. “Happy New Year’s!” I called out to my circle of observers — to my stranger with his strange news — and tried to retrace my steps, to find what remained of the weather crew.

That man had known something about Icehenge, I was certain of it. And that certainty changed my life.

My food had run out, and my memory was exhausted, so I decided to get away from the keyboard and my memoirs for a day or two, and hang around in the commons. Maybe I would run into Jones, or I could seek him out. Some people aboard, I had heard, were affronted because Jones had been invited along (by me). Theophilus Jones was an outcast, he was one of those strange scientists who defied the basic tenets of his field and others’. But I found the huge red-haired man to be one of the most intelligent people on the

In the kitchen I got a large bowl of ice cream, and went to a table to eat and read. The commons was empty — perhaps this was the sleep shift? I wasn’t sure.

I opened my crisp new book, pages still stiff around the ring binding, and began to read:

…We must suspect alien presence in the unsolved problem of human origins, for science has significantly failed to discover the beginnings of human evolution, the point at which human beings and a terrestrial species might meet; and the recent finds in the Urals and in southern India, in which fossilized human skeletons one hundred million years old have been found, show that the scientific description of human evolution held up to this time was wrong. Alien interference, in the form of genetic engineering, crossbreeding, or most likely, colonization, is almost a certainty.

So it is not impossible that a human civilization of high technology existed in prehistoric times — an earlier wave of history, now lost to us. That such a civilization would be lost to us is inevitable. Continents and seas have come and gone since it existed, and humanity itself must have come close to extinction more than once. If there had been a great and ageless city on the wide triangle of India, when it was a splinter of Gondwanaland inching north, what would we know of it now, crushed as it must have been in the collision between Asia and India, thrust deep beneath the Himalayas by the earth itself? Perhaps this is why Tibet is a place where humans have always possessed an ancient and intricate wisdom, and what we now know to be the oldest of written languages, Sanskrit. Perhaps some few of that ancient race survived the millennial thrust skyward; or perhaps there are caves the Tibetans have found, with deep fissures winding down through the mountain’s basalt to chambers in that crushed city…

My ice cream bowl was empty, so I got up and went to the kitchen to refill it, shaking my head over the passage in Jones’s book. When I returned, Jones himself was in the room, deep in conversation with Arthur Grosjean. They were at the long blackboard, and Grosjean was picking up a writing stick. He had been the chief planetologist on the

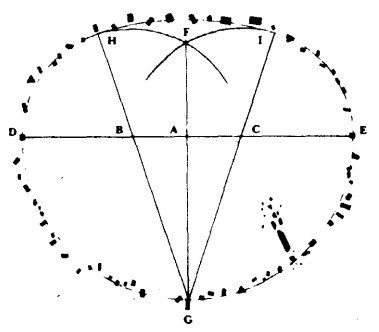

“First you draw a regular semicircle,” said Grosjean. “That’s the south half. Then the north half — the half closest to the pole, that is — is flattened.” He drew a horizontal diameter, and a semicircle below it. “We figured out the construction that will flatten the north half correctly. Divide the diameter into three parts. Use the two dividing points

|

“The construction,” Jones said. He took the writing stick and began making little rectangles around the circle.

“All the sixty-six liths are within three meters of this construction,” Grosjean said.

“And this is a prehistoric Celtic pattern, you say?” asked Jones.

“Yes, we discovered later that it was used in Britain in the second millennium B.C. But I don’t see how that supports your theory, Mr. Jones. It would be just as easy for later builders of Icehenge to copy the Celts as it would be for the Celts to copy earlier builders of Icehenge — easier, if you ask me.”

“Well, but you never can be sure,” Jones said. “It looks awfully suspicious to me.”

Then Brinston and Dr. Nimit walked in. Jones looked over and saw them. “So what does Dr. Brinston think of this?” he said to Grosjean. Brinston heard the question and looked over at them.

“Well,” Grosjean said uncomfortably, “I’m afraid that he believes our measurements of the monument were inaccurate.”

“What?”

Brinston left Nimit and approached the blackboard. “Examination of the holograms made of Icehenge show that the on-site measurements — which were not made by Dr. Grosjean, by the way — were off badly.”

“They’d have to be pretty inaccurate,” Jones said, turning back to the board, “to make this construction bad speculation.”

“Well, they were,” Brinston said easily. “Especially on the north side.”

“To tell you the truth,” Grosjean informed Jones, “I still believe the construction was the one used by the builders.”

“I’m not sure that’s a good attitude,” Brinston said, his voice smooth with condescension. “I think the fewer preconceived notions we have before we actually see it, the better.”

“I have seen it,” Grosjean snapped.

“Yes,” said Brinston, voice still cheerful, “but the problem isn’t in your field.”

Jones slammed down the writing stick, “You’re a fool, Brinston!” There was a shocked silence. “Icehenge is not exclusively your problem because you are

Jones’s lip curled and Brinston stepped back, jaw suddenly tensed. “Come on, Arthur,” said Jones. “Let’s continue our conversation elsewhere.” He stalked out of the room, and Grosjean followed.

I remembered Nederland saying to me, It will become a circus. Brinston approached us, his face still tense. He noticed Nimit and me staring, and looked embarrassed. “A touchy pair,” he said.

“They’re not touchy,” I said. “You were harassing them, being a disruption.”

“Not wanting to play with

“Working,” he sneered. “Your work is done.” He walked into the kitchen, leaving Nimit and me to stare silently at each other.

Waystation — where I lived for fifteen years, not twenty — is the freight train, the passenger express, the permanent highspeed rocket of the Outer Satellites. It uses the sun and the gas giants as buoys, or gravity handles to swing around. It travels about the same distance as Saturn’s orbit in a year — a fast rock. It began as an idea of Caroline Holmes, the shipping magnate who built most of the Jupiter colonies; and she profited from it most, as she did from all the rest of her ideas. Her company Jupiter Metals took a roughly cylindrical asteroid, twelve kilometers long and around five across. The inside was hollowed out, one end was honeycombed by the huge propulsion station, and off it went, careening around the sun, constantly shifting orbit to make its next rendezvous.

I boarded it on a shuttle from Titan, in 2594. My name had finally come up on the hitchhiker’s list — the Outer Satellites Council provides free travel between the satellites, which otherwise would be too expensive for most individuals, and all you have to do is put your name on the list and wait for it to come to the top. I had waited four years.

Jumping on Waystation is like running in a relay race, and handing the baton to a runner five times faster than you — for getting a transfer craft up to Waystation’s velocity would defeat the purpose of having Waystation at all. Our shuttle craft was moving at top speed, and we passengers were each in anti-G chambers (called the Jelly) within tiny transfer craft. As Waystation flashed by the transfer vessels were fired after it, at tremendous acceleration, and the transfer crews on Waystation then snagged them and they accelerated some more, while the crews reeled us in.

Even in the Jelly the sudden accelerations were a strain. At the moment we were snagged, the breath was knocked out of me and I blacked out for a second. While I was unconscious I had a brief vision, intense and clear. I could see only black, except for the middle distance, directly before me: there stood a block of ice, cut in the shape of a coffin. And frozen in this glittering bier was me, myself — eyes wide and staring back at me.

The vision passed, I came to, shook my head, blinked. Waystation people helped me out of the Jelly, and I joined the other passengers in a receiving room. Several of them looked distinctly ill.

A Waystation official greeted us, and without further ceremony we were escorted through the Port and into the city itself. It was crowded at that time — drop-offs to Jupiter were just about to be made, and there were a lot of merchants in town, moving goods. I found a job washing dishes first thing, and then went out to the front end of Waystation, rented a suit and took the elevator to the surface near the methane lake. I sat there for a long time. I was on Waystation, the next step outward.

For I was still chasing Icehenge, yes, I was. My dreams, my acceleration-induced visions, my studies, my physical movement, all centered around the idea of the megalith. And after the chance meeting with the stranger on Titan — after my most cherished story had been shattered — I returned to my studies with an obsessive purpose, fueled by a vague sense of betrayal: I was going to find out who put that damn thing there.

And I took my time about it, too. None of Nederland’s hasty rushing about. In his need for precedence — his drive to be the one who

Some years after my move to Waystation I woke up one morning in the park, arms wrapped around a very young girl. The Sunlight had just come on and was still at half strength, giving its comforting illusion of morning. I stood up, went through a quick salute-to-the-sun exercise to alleviate the stiffness in my legs. The girl woke up. In the light she looked about fifteen or sixteen. She stretched like a cat. Her coat was wrinkled. She had joined me the previous night, waking me up to do so, because it was cold, and I had a blanket. It had felt good to sleep with someone, to spoon together for warmth, to feel human contact even through coats.

She got up and brushed off her pants. She looked at me and smiled.

“Hey,” I said. “You want to go over to the Red Cafe and get some breakfast?”

“No,” she said. “I have to go to work. Thanks for taking me in.” She turned and walked off through the park. I watched her until a stand of walnut blocked my sight of her. Rare to see someone so young on Waystation.

I went and ate — said good morning to Dolores the cashier as she typed my money from me to them, but she just shrugged. I went out and strolled aimlessly up the curved streets. Sometimes the real world seems just like the inside of a holo, where nothing you say or do will have any effect on what is happening around you. I hate mornings like that.

For something to do I went down to the post office and checked my mail. And there, in my March 2606 issue

Davydov and Icehenge: A Re-examination by Edmond Doya

There are many reasons for supposing that the megalith on Pluto called “Icehenge” was constructed within the last one hundred and fifty years, by a group that has not yet been identified.

1) 2443, when the Ferrando Corporation’s Ferrando-X spaceships were first made available to the public, is the earliest date at which ships capable of making the round trip from the outermost spaceship ports to Pluto and back existed. Before that date, because Pluto was at its aphelion, and on the opposite side of the solar system from Jupiter and Saturn, and because of the limited capabilities of all existing spaceships before the Ferrando-Xs, Pluto was simply out of human reach. So a

2) The Davydov Theory, which is the only theory that pushes back this necessary time limit, asserts that the megalith was built by asteroid miners who were leaving the solar system in a modified pair of spaceships of the PR Deimos class. But a close examination of the evidence supporting this theory has revealed the following discrepancies:

a) The

This fact becomes more disturbing with the introduction of new evidence concerning these sole supports for the Davydov Theory:

b) Jorge Balder, professor of history at the University of Mars, Hellas, searched the Physical Records Annex in Alexandria in 2536, as part of his research on a related incident in early Martian history. His records show that he searched Cabinet 14A23546 (all six drawers) at that time, and he catalogued its contents. In his catalogue there is no mention of the file found in 2548 by Professor Hjalmar Nederland, on Oleg Davydov and the Mars Starship Association. The implication is that the file was placed in the cabinet at a later date.

c) The records of the New Houston excavation show that William Strickland and Xhosa Ti, working under Professor Nederland, did a seismic scan of precisely the area in which the abandoned field car was found, two weeks before it was discovered. Their scan showed no sign of such an object. During the intervening two weeks a storm kept all workers out of the area, and the car was found because of a landslide that could have easily been triggered by explosives.

The article went on to list exactly what was documented about Davydov and the rest, and to show where information about them and the MSA should have been located but wasn’t. After that were suggestions for further inquiry, including a physical examination and dating, if possible, of the abandoned field car, Emma Weil’s notebook, and the file from Alexandria. My conclusion was tentative, as was only proper at that point, but still it was a shocker: “…Thus we are inclined to believe that these artifacts, and the Davydov theory that depends upon them, have been manufactured, apparently by the same agents who are responsible for the construction of Icehenge, and that they constitute a ‘false explanation’ for the megalith, linking it to the Martian Civil War when it apparently was erected at least two centuries later.”

Yes, that would open their eyes all right! It threw the whole issue into question again. And

Quitting time at the restaurant. I went over to see Fist Matthews, one of the cooks. “Fist, can you lend me ten till payday?”

“Why do you want money, wild man? The way you eat here you ain’t hungry.”

“No, I need to pay off the post office before they’ll let me see my mail.”

“What’s a dishwasher like you doing with mail? Never mess with it myself. Keep your friends where you can see them, that’s what I say.”

“Yeah, I do. It’s my foes I want to hear from! Listen, I’ll pay you back payday, that’s the day after tomorrow.”

“You can’t wait till then? Oh all right, what’s your number…”

He went to the restaurant’s register and made the exchange. “Okay, you got it. Remember payday.”

“I will. Thanks, Fist.”

“Don’t mention it. Hey, me and the girls are going body-surfing when we get off — want to come along?”

“I’ve got to check my mail first, but then I’ll think about it.”

I threw a few more dishes on the washer belt — grabbed a piece of lobster tail the size of my finger, tossed it in my mouth, fuel for the fire, waste not want not — until my replacement arrived, looking sleepy.

The streets of Waystation were as empty as they ever get. In the green square of the park, up above me on the other side of the cylinder, a group was playing cricket. I hurried past one of my sidewalk sleeping spots, stepping over prone figures. As I neared the post office I skipped. I hadn’t been able to afford to see my mail for several days — it happened like that at the end of every month. Post office has mail freaks over a barrel, and they know it.

When I got there it was crowded, and I had to hunt for a console. More and more people were going to general delivery, it seemed, especially on Waystation where almost everyone was transient.

I sat down before one of the gray screens and began typing, paying off the post office and identifying myself, calling up my correspondence from the depths of the computer. I sat back to read.

Nothing! “Damn it!” I shouted, startling a young man in the booth next to me. Junk mail, nothing but junk. Why had no one written? “No one writes to Edmond,” I muttered, in the singsong I had given the phrase over the years. There was an issue of

I blanked the screen and left. Keep your friends where you can see them. Well, it was good advice. There were more people in the streets, on the trams, going to work, getting off work. I didn’t know any of them. I knew almost all the locals on Waystation, and they were good people, but suddenly I missed my old friends from Titan. I wanted something… something I had thought the mail could give me; but that wasn’t quite right either.

I hated mornings like this. I decided to take up Fist’s invitation, and got on a tram going to the front of the town. At the last stop I got off and took the short elevator through the wall of the asteroid to the surface. Leaving the elevator I went to the big window overlooking Emerald Lake. We were somewhere near Uranus, so the lake was full. The changing room, however, was nearly empty. I went to the ticket window, and they took more of Fist’s ten. The suit attendant helping me looked sleepy, so I checked my helmet seam in the mirror. The black, aquatic creature — like a cross between a frog and a seal — stared back at me out of its facemask, and I smiled. In the reflection the humorless fish grin appeared. The slug-broad head, webbed and finned handscoops, long finny feet, torso fins, and the cyclopslike facemask transformed me (appropriately, I thought) into an alien monster. I walked slowly into the lock, lifting my knees high to swing my feet forward.

The outer lock door opened, I felt the tiny rush of air, and I was outside, on my own. It felt the same, but I breathed quicker for a time, as always; I’d not spent very much time in the open recently. A ramp extended out into the lake, and I waddled to the end of it.

Around the lake, flat blue-gray plains rose up to the close horizon of an ancient worn- down crater wall. It looked like the surface of any asteroid. Waystation’s existence — the hollowed interior, the buildings and people, the complicated spaceport, the huge propulsion station on the other end, the rock’s extraordinary speed — all could seem the work of an excited fancy, here by this lake of liquid methane, trapped in an old crater.

Below me the stars were reflected, green as — yes, emeralds — in the glassy surface of the methane. I could see the bottom, three or four meters below. A series of ripples washed by, making the green stars dance for a moment.

Out on the lake the wave machine was a black wall, hard to distinguish in the pale sunlight. Its sudden shift toward me (which looked like a visual mistake caused by blinking) marked the creation of another tall green swell. The swells could hardly be seen until they crossed the submerged crater wall near the center of the lake; then they rose up, pitched out and fell, breaking in both directions around the submerged crater, throwing sheets of methane like mercury drops into space, where they floated slowly down.

I dove in. Under the surface I was effectively weightless, and swimming took little effort. Over the sound of my breath was the steady

A few other swimmers were out, and I guessed some of my fellow restaurant workers were among them. I swam around the break, out beyond the crater, where the swells first hit the shelf and started to rise to their full height, which today was nearly ten meters. Three of my friends were out there, Wendy, Laura, and Fist; I waved to them, then floated on my back and waited for them to take their turns. Rising and falling on those smooth swells I felt quite inhuman; all that I saw, felt, and heard — even the sound of my own breath — was strange, alien, too sublime for human sensibility.

Then I was alone at the point break. A swell approached and I backstroked away from it, toward the point where it would first break, adjusting my speed so I would be just outside that point when the wave picked me up.

The wave reached me and I felt its strong lift. I turned luxuriously onto my stomach, skimmed down the steepening face until I felt that the swell was pitching out over me. From my thighs up I was clear of the methane, skating on my hand — fins — I turned them left, and swerved across the wave, just ahead of the break, flying, flying… I moved my feet to retard my speed a fraction, and the roof of the breaking wave moved ahead of me. It got dark. I was in the tube. My hands were below me, jammed into the methane to keep me from falling down the face. I was motionless yet flying, propelled through the blackness at tremendous speed by the liquid which rushed up past my left shoulder, arched over my head, and fell out beyond my right shoulder. Before me there was a huge tunnel, and at the end of this swirling obsidian tube a small ellipse of velvet black, packed with stars.

The opening got smaller, indicating that the wave was past the submerged crater, and receding. I dropped to gain speed, turned back up and shot through the hole, over the swell and back onto the smooth glassy surface, under the night.

Swimming slowly back to the point break, I watched another swimmer spin silently across the next rushing wall. She rose too high and was thrown over with the lip of the wave. If she hit the crater reef and broke the seal of her suit, she would freeze instantly — but she knew that, and would be careful to avoid being forced too deep.

I radioed the shore and had them pipe Gregorian chants into my headphones; and I swam, and rode waves, and hummed with the chants when I could catch my breath, and thought not at all. And later I switched over to the common band, and talked at great length with Fist and Wendy and Laura, as we analyzed every wave and every ride. I swam till there was too much sweat in my suit, and not enough oxygen.

Back on the tram into town, I felt good: free and self-sufficient, cosmopolitan, ready to work. It was time to attack the next facet of the Icehenge problem: the identity of its builder. My research had given me a good idea of who it might be, but the problem would be to prove it — or even to make a convincing case. And the next day I checked my mail again, and there was a long rambling letter from Mark Starr. PRINT, I typed, and out of the slot in the side of the console it appeared, blue ink on gray paper, just as always.

One day I went down to Waystation’s News and Information Center in search of the latest Nederland press conference. The lobby of the center was nearly empty, and I went directly into a booth. The index I called up listed only Nederland’s regularly scheduled lectures, and I had to search through the new entries to find the press conference I wanted. Finally I discovered it and typed the code to run it, then sat back in the center chair of the booth to watch.

The room darkened. There was a click and I was in a large conference room, fully lit, filled with the holo images of upper-class Martians: reporters, students, officials (as in any Martian holo there were a lot of these), and some scientists I recognized. And there was Nederland, moving down an aisle next to me, toward a podium at the front. I moved through people and chairs to the aisle, and stood in front of Nederland. He walked right through me. Smiling at my little joke, and at my quick moment of involuntary fright at the unfelt collision, I said, “You’ll see me yet,” and kicked about until I relocated my chair.

Nederland reached the podium and the irregular percussion of voices died. He was a small man, and only his head showed over the podium’s top. Underneath his wild black hair was a look of triumph; his bright red cheeks were blazing with excitement. “You hopeless old romantic,” I said. “You’ve got something up your sleeve, you can’t fool me.”

He cleared his throat, his usual sign that he was taking over. “I think my statement will answer most of the questions you have today, so why don’t I start with that, and then we’ll answer any questions you might have.”

“Since when has it been any different?” I asked, but it was the only response. Nederland looked at his notes, looked up — his eyes crossed mine — and he extended a benedictory hand.

“The recent critics of the Davydov explanation claim that the Pluto monument is a modern hoax, and that in my work on the subject I have ignored the physical evidence. The absence of any disturbance in the regolith around the site, and our inability to find any signs of construction, are cited as facts which contradict or do not fit my explanation.

“I submit that it is the critics who are ignoring the physical evidence. If the Davydov expedition did not build Icehenge, why did Davydov himself study the megalithic cultures of Terra?”

“What?” I cried.

“What are we to make of his stated intention to leave some sort of mark on the world? Can we label it coincidence that Davydov’s ship disappeared just three years before the date found on Icehenge? I think not…”

He went on, outlining the same arguments he had been espousing for the last fifty years. “Come on,” I groaned, “get down to it.” He droned on, ignoring the fact that his critics had shown the whole Davydov story to be part of the hoax. “I know you’ve got something new up your sleeve, let’s see it.” Then he flipped over a notecard, and an involuntary smile creased his face. I sat forward.

“My critics,” he said in his high voice, “are simply attacking in a purely destructive way. Aside from the vague claim that the monument is a modern hoax — perpetrated by whom, they cannot say — there is no theory to replace mine, and nothing to explain away the evidence found in the archives on Mars—”

“Oh, my God, exactly wrong!”

“-Which are constantly being re-ordered and refiled.”

“Oh. You hope.”

“The general claim of people like Doya, Satarwal, and Jordan, is that there is nothing at the site which will prove Icehenge’s age. On the other hand, there is nothing there that shows the monument to be modern, either, which given the sophistication of dating methods there almost certainly would be, if it were indeed modern.

“In fact, there is now evidence conclusively proving that Icehenge

“Thus there is nothing that factually disproves the Davydov theory — there are only the doubts and fanciful speculations of detractors, some of whom have clear political motivations. And there

Pandemonium broke loose among the previously attentive figures around me. Questions were shouted out, incomprehensible under the noise of cheers and applause. “Oh, shut up,” I said to the image of the woman next to me, who was clapping. As questions became audible — some of them were good ones — order was re-established, but apparently the news service people had considered the question and answer period unimportant. With another click the scene disappeared, and I was again in the dark, silent holo room. Lights came on. I sat.

Had Nederland proved his theory at last? Was the stranger on Titan wrong after all? (and I as well?) “Hmm,” I said. Apparently I was going to have to start looking into dating methods.

I woke up in the alley behind one of Waystation’s main boulevards. I had been sleeping on my side, and my neck and hip were sore. I took off my coat and shook the dust off it. Pushed my fingers through my hair and made it all lie down flat, brushed my teeth with a fingernail, looked around for something to drink. Put my coat back on. Flapped my arms.

Around me prone figures were still slumbering. Waking up is the worst part of living on the streets of Waystation; they drop the temperature down to ten degrees during the nights, to encourage travelers to take rooms. Helping out the hotel trade. A lot of people stay on the streets anyway, since most of them are transients. They aren’t bothered in any way aside from the cold, so they save their money for things more important than a room for the night. We all have the necessary shelter, inside this rock.

Low on money again, but I needed something to eat. Onto the tram.

Down at the spaceport I spent my last ten in Waystation’s cheapest restaurant. With the change I bought myself a bath, and sat in a corner of the public pool resting and thinking nothing.

When I was done I felt refreshed, but I was also broke. I went to my restaurant and hit Fist for another ten, then I walked around to the post office. Not much mail; but there at the end, to my great surprise, was a letter from a Professor Rotenberg, head of the Fine Arts Lecture Series at the Waystation Institute for Higher Learning (which, like many of the institutions on Waystation, had been founded by Caroline Holmes). Professor Rotenberg, who had enjoyed my “interesting revisionist articles” on Icehenge, wondered if I would consider accepting a semester’s employment as lecturer and head of a seminar studying the Pluto megalithic monument literature — “My my my,” I said, and typed out instructions to print the letter with my mouth hanging wide open.

I went out of my cabin for the first time in a while, to restock my supply of crackers and orange juice. The wood and moss hallways of

Yesterday was my birthday. I was sixty-two years old. One tenth of my life done and gone, the endless childhood over.

Those years feel like eternity in my head, and the thing is hardly begun. Hard to believe. I thought of the ancient stranger I had met on Titan, and wondered what it meant to live so unnaturally long, and then die anyway. What have we become?

When I am as old as that stranger, I will have forgotten these first sixty-two years and more. Or they will recede into depths of memory beyond the reach of recollection — the same as forgotten — recollection being a power inadequate to our new time scale. And how many other powers are like it?

Autobiography is now the necessary extension of memory. Five centuries from now I may live, but the

My father sent me a birthday poem that arrived just last night. He’s given me one every birthday now for fifty-four years; they’re beginning to make quite a volume. I’ve encouraged him to put them and the rest of his poems into the general file, but he still refuses. Here is the latest:

Walking back to my room with my food, saying his poem to myself in my mind, I realized that I miss him.

I met with the Institute seminar I was to teach about a month after I got the invitation from Professor Rotenberg. At my urging we decided to meet at the back table of a pub across the street from the Institute, and we moved there forthwith.

It quickly became clear that they had read the literature on the subject. What more could I tell them?

“Who put it there?” said a man named Andrew.

“Wait a minute, start at the beginning.” That was Elaine, a good-looking hundredish woman on my left. “Give us your background, how you got into this.”

I told them my story as briefly as possible, feeling sheepish as I described the random meeting that had triggered my whole search. “…So you see, essentially, I believe I met someone who had a hand in constructing Icehenge, which necessarily eliminates the Davydov party from consideration.”

“You must have been astonished,” Elaine said.

“For a while. Astonished, shocked — betrayed… but soon the idea that the monument was put there by someone other than Davydov obsessed me. It made the whole problem unsolved again, you see.”

“Part of you welcomed it.” That was April, a very attentive woman sitting across from me.

“Yeah.”

“But what about Davydov?”

“What about Nederland?” asked April. She had a rather sharp and scornful way of speaking.

“I wasn’t sure. It didn’t seem possible that Nederland could be wrong — there were all those volumes, the whole edifice of his case. And I had believed it for so long. Everyone had. If he was wrong, what then of Davydov? Or Emma? Many times when I thought about it the certainty I had felt that night — that that stranger

“How did you start?”

“With a premise. Induction, same as Nederland. I started with the theory that Icehenge was not built until humans were capable of getting to Pluto, which struck me as very reasonable. And there were no spaceships that could have taken us there and back until 2443. So Icehenge was a relatively modern construct, made anonymous in the deliberate attempt to obscure its origins.”

“A hoax,” April said.

“Well, yes, in a way, although it’s not the structure that’s a hoax, I mean it is definitely there no matter who set it up—”

“The Davydov expedition, then.”

“Right. Suddenly I had to wonder whether Davydov and Emma — whether any of them had existed at all.”

“So you checked Nederland’s early work.” This from Sean, a very big, bearded man.

“I did. I found that both Davydov and Emma had actually existed — Emma held some Martian middle-distance running records for several years, and some records of their careers were extant. And they both disappeared with a lot of other people in the Martian Civil War. But the only things connecting them with Icehenge were a file in the Alexandrian archives that apparently was planted, and Emma Weil’s journal, which was excavated outside New Houston. Now I got a chemist named Jordan interested in the case, and he has been investigating the aging of the field car that the journal was found in. You know metal oxidizes to an extent when buried in Martian soil, and the rate is measureable — and Jordan’s analysis of the field car seems to indicate that it was

“So what did you do, then?” Sean asked.

“I made a list of qualities and attributes that the builder of Icehenge

“But you could make assumptions forever,” April said. “What did you do?”

“Uh. I did research. I sat in front of a screen and punched out codes, read the results, found new indexes, punched out more codes. I looked through shipping records, equipment manufacturing records, sales records — I investigated various rich people. That sort of thing. It was boring work in some ways, but I enjoyed doing it. At first I thought of myself as working my way through a maze. Then that seemed the wrong image. In front of a library screen I could go anywhere. Because of the access-to-information laws I could look in every file and record that existed, except for the illegal secret ones — there are a lot of those — but if they had code call-ups, you know, were hidden somewhere in larger data banks — then I could probably get into those too. I bumped into file freaks and learned new codes, and learning them took me into data banks that taught me even more. Trying to visualize it, I could see myself as a tiny component in a single communications network, a multibank computer complex that spanned the solar system — a dish-shaped, invisible, seemingly telepathic web, a wave pattern that added one more complication to the quark dance swirling in the sun’s gravity well. So I was not in a maze, I was above it, and I could see all of it at once — and its walls formed a pattern, had a meaning, if I could learn how to read it…”

I stopped and looked around. Blank faces, neutral, tolerant nods. “You know what I mean?” I asked.

No answers. “Sort of,” said Elaine. “But our time’s up.”

“Okay,” I said. “More next time.”

One night after a party in the restaurant’s kitchen I wandered the streets, my mind in a ferment. The Sunlight was off and the other side of the cylinder was a web of streetlights and colored neon points. It was the day after payday, so I stopped at the News and Information Center and waited until I could get a booth. When I got one I sat down and aimlessly called up indexes. Something was bothering me, but I didn’t know exactly what it was; and now I only wanted to be distracted. Eventually I selected Recreation News, which played continuously.

The room darkened and then revealed a platform in space. The scene moved to one side and I could see we were on the extension of a small satellite, in a low orbit around an asteroid.

The lilting voice of one of the sports commentators spoke. “The ancient game of golf has undergone yet another transformation out here on Hebe,” he said. We moved farther out onto the platform, and two golfers appeared at the edge of it, in thin hoursuits. “Yes, Philip John and Arafura Aloesi have added a new dimension to their golfing on and around Hebe. Let’s hear them describe it for themselves. Arafura?”

“Well, Connie, we tee off from up here, that’s about it in a nutshell. The pin is back down there near the horizon, see the light? It’s two meters wide, we figured we deserved that much from up here. Mostly we play hole-in-one.”

“What do you have to think about when you’re hitting a shot from up here, Phil?”

“Well, Connie, we’re in a Clarke orbit, so we don’t have to worry about orbital velocity. It’s a lot like every other drive, actually, except you’re higher up than usual—”

“You have to watch out for hitting it too hard; gravity’s not much around a small rock like this, if you drive with a one wood you’re liable to put the ball in orbit, or out in space even—”

“Yeah, Connie, I generally use a three iron and shoot down at it, that works best. Sometimes we play where we have to put the ball through one orbit before it can hit the ground, but it’s hard enough as it is, and—”

“All right, let’s see you guys put one down there.”

They swung and the balls disappeared.

“Now how do you see where it’s hit, guys?”

“Well, Connie, we got this radar screen following them down to the horizon — see, mine’s right on track — then the green has a hundred-meter diameter, and if we land on that it shows on this screen here. Here, they’re about to hit—”

Nothing appeared on the green screen beside them. Phil and Arafura looked crestfallen.

“Well, guys, any future plans for this new twist?”

Phil brightened. “Well, I was thinking if we were to set up just off Io, we could use the Red Spot as the hole and shoot for that. No problem with gravity there—”

“Yes, that’d be one hell of a fairway. And that’s all from Hebe for now, this is Connie McDowell—”

My time ran out and the room was dark, then bright with roomlight. Eventually the attendant came in and roused me. Again my mouth was hanging open: the astonishment of inspiration. I jumped up laughing. “That’s it!” I said, “golf balls!” Still laughing wildly: “I got the old fool this time!” The attendant stared at me and shook his head.

Only a month later (I had written it in a week) a long letter of mine appeared in the Commentary section of

There is no good evidence concerning the age of Icehenge. This is because most dating methods that have been developed by archaeologists are applicable to substances or processes found only on Terra. Some of these have been adapted for use on Mars, but on planetary bodies without atmospheres, most of the processes that are measured simply do not occur.

The ice of Icehenge, it has been determined, is about two billion years old. But when that ice was cut into beams and placed on Pluto has proven more difficult to determine. Two changes in the ice beams offer possible dating methods. First, a certain amount of the ice has sublimed spontaneously, but at seventy degrees Kelvin this process is extremely slow, and its effects at Icehenge are too small to measure. (This argues against any very great age for the megalith — those ages proposed by all of the “prehistoric” theories — but is no help in determining the date of construction more precisely.)

An attempt has been made to measure the second change occurring in the ice, which is the pitting that results from the fall of micrometeorites. Professor Mund Stallworth, with the help of Professor Hjalmar Nederland and the Holmes Foundation, has developed a micro-meteorite count method by which he claims to have dated the monument. This method is the equivalent of the terrestrial dating method of patination, and like patination it relies on an intimate knowledge of local conditions if it is to achieve any accuracy. Stallworth has assumed, and assumed only, that micrometeor fall is a constant both temporally and spatially. After making this assumption he has been fairly rigorous, and has taken counts on artificial surfaces on Luna and in the asteroids to establish a reliable short-term time chart. According to his calculations, micrometeors have fallen on Icehenge for a thousand years plus or minus five hundred. This makes Icehenge at least a hundred and fifty years older than the 2248 dating, but is considered close enough by Nederland, who has used Stallworth’s results to support his theory.

But the main problem with this dating (aside from the fact that the method is based on an assumption) is that the micrometeor fall on Icehenge could be part of the manufactured evidence. Micrometeorites are, for the most part, carbon dust. A handful of carbon dust sprinkled from a few hundred meters over the monument would create exactly the same effect as a thousand years of natural micrometeor fall. There would be no way of telling the difference.

Also, this is a precaution that would occur very quickly to the builders of Icehenge if they were attempting to make the monument appear older than it really is, for micrometeorites would be the only force acting on the structure over the short term. Though a method for measuring this action did not exist at the time of the monument’s construction (and still does not, in my opinion), the existence of micrometeor fall was known, and so the dating method could be both foreseen and dealt with, by an artificial fall. Given the elaborate nature of this hoax it is a possibility more likely than not—”

At the next seminar meeting, in the same pub, after we had had a few drinks, Andrew waved a finger at me. “So give, Edmond,” he said. “We want to know who put it there.”

I put down my glass. I had never written this down; never said it to anybody. All their eyes were on me.

“Caroline Holmes,” I said.

“What?”

“No!”

“What?”

“No, nooooo…”

They quieted down. Sean said, “Why?”

“Start from the beginning,” Elaine said.

I nodded. “It started with shipping records. You remember the list of criteria I gave you last time? Well, it seemed to me that access to a spaceship would be the best point on the list for narrowing down the group of potential suspects. The Outer Satellites Council licenses all spaceships, and keeps flight logs for all flights made. The same is true for Mars and Terra. So the flight to Pluto would have to be made, um, off the books, you know. So I started checking the records of all the spaceships capable of making the round trip to Pluto—”

“My God!” Sean said. “What a chore.”

“Yes. But there are a finite number of those ships, and I had a lot of time. I wasn’t in any hurry. And eventually I found that Caroline Holmes’s shipyards had tucked away a couple of Ferrando-X spaceships for five years in the 2530s, for unspecified repairs. So I started investigating Holmes herself. She fulfills all the criteria: she’s rich enough, she has the equipment, the spaceships, the employees that depend on her for everything and wouldn’t be likely to talk. Her foundation financed the development of Stallworth’s micrometeorite dating method, by giving him a grant. And there was something about her — she wasn’t obviously secretive, I mean we all know something about her — but it was curious how little I could find out about her once I tried. Especially about her earlier years.”