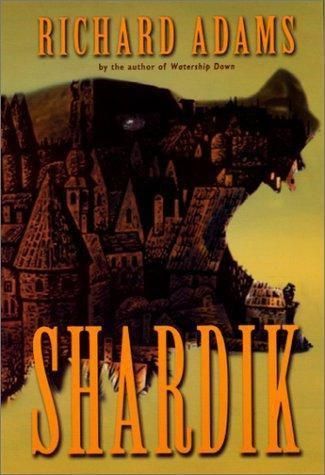

"Shardik" - читать интересную книгу автора (Adams Richard)

|

Richard Adams

Shardik

Lest any should suppose that I set my wits to work to invent the cruelties of Genshed, I say here that all lie within my knowledge and some – would they did not – within my experience. Behold, I will send my messenger… But who may abide the day of his coming? And who shall stand when he appeareth? For he is like a refiner's fire. Malachi. Chapter III

Superstition and accident manifest the will of God. C. G.Jung Book I

1 The Fire

Even in the dry heat of summer's end, the great forest was never silent. Along the ground – soft, bare soil, twigs and fallen branches, decaying leaves black as ashes – there ran a continuous flow of sound. As a fire burns with a murmur of flames, with the intermittent crack of exploding knots in the logs and the falling and settling of coal, so on the forest floor the hours of dusky light consumed away with rustlings, patterings, sighing and dying of breeze, scuttlings of rodents, snakes, lizards and now and then the padding of some larger animal on the move. Above, the green dusk of creepers and branches formed another realm, inhabited by the monkeys and sloths, by hunting spiders and birds innumerable -creatures passing all their lives high above the ground. Here the noises were louder and harsher – chatterings, sudden cacklings and screams, hollow knockings, bell-like calls and the swish of disturbed leaves and branches. Higher still, in the topmost tiers, where the sunlight fell upon the outer surface of the forest as upon the upper side of an expanse of green clouds, the raucous gloom gave place to a silent brightness, the province of great butterflies flitting across the sprays in a solitude where no eye admired nor any ear caught the minute sounds made by those marvellous wings.

The creatures of the forest floor – like the blind, grotesque fish that dwell in the ocean depths – inhabited, all unaware, the lowest tier of a world extending vertically from shadowless twilight to shadcless, dazzling brilliance. Creeping or scampering upon their furtive ways, they seldom went far and saw little of sun and moon. A thicket of thorn, a maze of burrows among tree-trunks, a slope littered with rocks and stones – such places were almost all that their inhabitants ever knew of the earth where they lived and died. Born there, they survived for a while, coming to know every inch within their narrow bounds. From time to time a few might stray further – when prey or forage failed, or more rarely, through the irruption of some uncomprehended force from beyond their daily lives.

Between the trees the air seemed scarcely to move. The heat had thickened it, so that the winged insects sat torpid on the very leaves beneath which crouched the mantis and spider, too drowsy to strike. Along the foot of a tilted, red rock a porcupine came nosing and grubbing. It broke open a tiny shelter of sticks and some meagre, round-cared little creature, all eyes and bony limbs, fled across the stones. The porcupine, ignoring it, was about to devour the beetles scurrying among the sticks when suddenly it paused, raised its head and listened. As it remained motionless a brown, mongoose-like creature broke quickly through the bushes and disappeared down its hole. From further away came a sound of scolding birds.

A moment later the porcupine too had vanished. It had felt not only the fear of other creatures near by, but also something of the cause – a disturbance, a vibration along the forest floor. A little distance away, something unimaginably heavy was moving and this movement was beating the ground like a drum. The vibration grew until even a human ear could have heard the irregular sounds of ponderous movement in the gloom. A stone rolled downhill through fallen leaves and was followed by a crashing of undergrowth. Then, at the top of the slope beyond the red rock, the thick mass of branches and creepers began to shake. A young tree tilted outwards, snapped, splintered and pitched its length to the ground, springing up and down in diminishing bounds on its pliant branches, as though not only the sound but also the movement of the fall had set up echoes in the solitude.

In the gap, half-concealed by a confused tangle of creepers, leaves and broken flowers, appeared a figure of terror, monstrous beyond the nature even of that dark, savage place. Huge it was – gigantic -standing on its hind legs more than twice as high as a man. Its shaggy feet carried great, curved claws as thick as a man's fingers, from which were hanging fragments of torn fern and strips of bark. The mouth gaped open, a steaming pit set with white stakes. The muzzle was thrust forward, sniffing, while the blood-shot eyes peered short-sightedly over the unfamiliar ground below. For long moments it remained erect, breathing heavily and growling. Then it sank clumsily upon all fours, pushed into the undergrowth, the round claws scraping against the stones – for they could not be retracted -and smashed its way down the slope towards the red rock. It was a bear – such a bear as is not seen in a thousand years – more powerful than a rhinoceros and heavy as eight strong men. It reached the open ground by the rock and paused, throwing its head uneasily to one side and the other. Then once more it reared up on its hind legs, sniffed the air and on the instant gave a deep, coughing bark. It was afraid.

Afraid – this breaker of trees, whose tread shook the ground – of what could it be afraid? The porcupine, cowering in its shallow burrow beneath the rock, sensed its fear with bewilderment. What had driven it wandering through strange country, through deep forest not its own? Behind it there followed a strange smell; an acrid, powdery smell, a drifting fear.

A band of yellow gibbons swung overhead, hand over hand, whooping and ululating as they disappeared down their tree-roads. Then a pair of genets came trotting from the undergrowth, passed close to the bear without a glance and were gone as quickly as they had come. A strange, unnatural wind was moving, stirring the dense mass of foliage at the top of the slope, and out of it the birds came flying – parrots, barbets and coloured finches, brilliant blue and green honeycreepers and purple jackdaws, gentuas and forest kingfishers -all screaming and chattering down the wind. The forest began to be filled with the sounds of hasty, pattering movement An armadillo, apparently injured, dragged itself past; a peccary and the flash of a long, green snake. The porcupine broke from its hole, almost under the bear's feet, and vanished. Still the bear stood upright, towering over the flat rock, sniffing and hesitating. Then the wind strengthened, bringing a sound that seemed to stretch across the forest from end to end – a sound like a dry waterfall or the breathing of a giant – the sound of the smell of the fear. The bear turned and shambled away between the tree-trunks.

The sound grew to a roaring and the creatures flying before it became innumerable. Many were almost spent, yet still stumbled forward with open mouths set in snarls and staring eyes that saw nothing. Some tripped and were trampled down. Drifts of green smoke appeared through gaps in the undergrowth. Soon the glaucous leaves, big as human hands, began to shine here and there with the reflection of an intermittent, leaping light, brighter than any that had penetrated that forest twilight. The heat increased until no living thing – not a lizard, not a fly – remained in the glade about the rock. And then at last appeared a visitant yet more terrible than the giant bear. A single flame darted through the curtain of creepers, disappeared, returned and flickered in and out like a snake's tongue. A spray of dry, sharp-toothed leaves on a zeltazla bush caught fire and flared brightly, throwing a dismal shine on the smoke that was now filling the glade like fog. Immediately after, the whole wall of foliage at the top of the slope was ripped from the bottom as though by a knife of flame and at once the fire ran forward down the length of the tree that the bear had felled. Within moments the place, with all its features, all that had made a locality of smell, touch and sight, was destroyed for ever. A dead tree, which had leaned supported by the undergrowth for half a year, fell burning across the red rock, splintering its cusps and outcrops, barring it with black like a tiger's skin. The glade burned in its turn, as miles of forest had burned to bring the fire so far. And when it had done burning, the foremost flames were already a mile downwind as the fire pursued its way. 2 The River The enormous bear wandered irresolutely on through the forest, now stopping to glare about at its unknown surroundings, now breaking once more into a shambling trot as it found itself still pursued by the hiss and stench of burning creepers and the approach of the fire. It was sullen with fear and bewilderment. Since nightfall of the previous day it had been driven, always reluctant yet always unable to find any escape from danger. Never before had it been forced to flight. For years past no living creature had stood against it. Now, with a kind of angry shame, it slunk on and on, stumbling over half-seen roots, tormented with thirst and desperate for a chance to turn and fight against this flickering enemy that nothing could dismay. Once it stood its ground at the far end of a patch of marsh, deceived by what seemed a faltering at last in the enemy's advance; and fled just in time to save itself from being encircled as the fire ran forward on either side. Once, in a kind of madness, it rushed back on its tracks and actually struck and beat at the flames, until its pads were scorched and black, singed streaks showed along its pelt. Yet still it paused and paced about, looking for an opportunity to fight; and as often as it turned and went on, slashed the tree-trunks and tore up the bushes with heavy blows of its claws.

Slower and slower it went, panting now, tongue protruding and eyes half-shut against the smoke that followed closer and closer. It struck one scorched foot against a sharpened boulder, fell, and rolled on its side, and when it got up became confused, made a half-turn and began to wander up and down, parallel to the line of the on-coming flames. It was exhausted and had lost the sense of direction. Choking in the enveloping smoke, it could no longer tell even from which side the fire was coming. The nearest flames caught a dry tangle of quian roots and raced along them, licking across one fore-paw. Then from all sides there sounded a roaring, as though at last the enemy were coming to grips. But louder still rose the frenzied, angry roaring of the bear itself as it turned at last to fight. Swinging its head from side to side and dealing tremendous, spark-showering blows upon the blaze around it, it reared up to its full height, trampling back and forth until the soft earth was flattened under its feet and it seemed to be actually sinking into the ground beneath its own weight. A long flame crackled up the thick pelt and in a moment the creature blazed, all covered with fire, rocking and nodding in a grotesque and horrible rhythm. In its rage and pain it had staggered to the edge of a steep bank. Swaying forward, it suddenly saw below, in a lurid flash, another bear, shimmering and grimacing, raising burning paws towards itself. Then it plunged forward and was gone. A moment later there rose the sound of a heavy splash and a hissing, quenching after-surge of deep water.

In one place and another, along the bank, the fire checked, diminished and died, until only patches of thicker scrub were left burning or smouldering in isolation. Through the miles of dry forest the fire had burned its way to the northern shore of the Telthearna river and now, at last, it could burn no further.

Struggling for a foothold but finding none, the bear rose to the surface. The dazzling light was gone and it found itself in shadow, the shadow of the steep bank and the foliage above, which arched over, forming a long tunnel down the river's marge. The bear splashed and rolled against the bank but could get no purchase, partly for the steepness and the crumbling of the soft earth under its claws, and partly for the current which continually dislodged it and carried it further downstream. Then, as it clutched and panted, the canopy above began to fill with the jumping light of the fire as it caught the last branches, the roof of the tunnel. Sparks, burning fragments and cinders dropped hissing into the river. Assailed by this dreadful rain, the bear thrust itself away from the bank and began to swim clumsily out from under the burning trees towards the open water.

The sun had begun to set and was shining straight down the river, tingeing to a dull red the clouds of smoke that rolled over the surface. Blackened tree-trunks were floating down, heavy as battering-rams, driving their way through the lesser flotsam, the clotted masses of ash and floating creeper. Everywhere was plunging, grinding and the thump and check of heavy masses striking one another. Out into this foggy chaos swam the bear, labouring, submerging, choking, heaving up again and struggling across and down the stream. A log struck its side with a blow that would have stove in the ribs of a horse and it turned and brought both fore-paws down upon it, half clutching in desperation, half striking in anger. The log dipped under the weight and then rolled over, entangling the bear in a still-smouldering branch that came slowly down like a hand with fingers. Below the surface, something unseen caught its hind-paws and the log drifted away as it kicked downwards and broke free. It fought for breath, swallowing water, ashy foam and swirling leaves. Dead animals were sweeping by – a striped makati with bared teeth and closed eyes, a terrian floating belly uppermost, an ant-eater whose long tail washed to and fro in the current. The bear had formed some cloudy purpose of swimming to the further shore – a far-off glimpse of trees visible across the water. But in the bubbling, tumbling midstream this, like all else, was swept away and once more it became, as in the forest, a creature merely driven on, in fear of its life.

Time passed and its efforts grew weaker. Fatigue, hunger, the shock of its burns, the weight of its thick, sodden pelt and the continual buffeting of the driftwood were at last breaking it down, as the weather wears out mountains. Night was falling and the smoke clouds were dispersing from the miles of lonely, turbid water. At first the bear's great back had risen clear above the surface and it had looked about it as it swam. Now only its head protruded, the neck bent sharply backwards to lift the muzzle high enough to breathe. It was drifting, almost unconscious and unaware of anything around it. It did not see the dark line of land looming out of the twilight ahead. The current parted, sweeping strongly away in one direction and more gently in the other. The bear's hind feet touched ground but it made no response, only drifting and tripping forward like a derelict until at length it came to rest against a tall, narrow rock sticking out of the water; and this it embraced clumsily, grotesquely, as an insect might grasp a stick.

Here it remained a long time in the darkness, upright like some tilted monolith, until at last, slowly relaxing its hold and slipping down upon all fours in the water, it splashed through the shallows, stumbled into the forest beyond and sank unconscious among the dry, fibrous roots of a grove of quian trees. 3 The Hunter The island, some twenty-five miles long, divided the river into two channels, its upstream point breaking the central current, while that 20 downstream lay close to the unburned shore which the bear had failed to reach. Tapering to this narrow, eastern end, the strait flowed out through the remains of a causeway – a rippling shallow, dangerously interspersed with deep holes – built by long-vanished people in days gone by. Belts of reeds surrounded most of the island, so that in wind or storm tie waves, instead of breaking directly upon the stones, would diminish landwards, spending their force invisibly among the shaking reed-beds. A little way inland from the upstream point a rocky ridge rose clear of the jungle, running half the length of the island like a spine.

At the foot of this ridge, among the green-flowering quian, the bear slept as though it would never wake. Below it and above, the reed-beds and lower slopes were crowded with fugitive creatures that had come down upon the current Some were dead – burned or drowned – but many, especially those accustomed to swim – otters, frogs and snakes – had survived and were already recovering and beginning to search for food. The trees were full of birds which had flown across from the burning shore and these, disturbed from their natural rhythms, kept up a continual movement and chatter in the dark. Despite fatigue and hunger, every creature that knew what it was to be preyed upon, to fear a hunting enemy, was on the alert. The surroundings were strange. None knew where to look for a place of safety: and as a cold surface gives off mist, so this lostness gave off everywhere a palpable tension – sharp cries of fear, sounds of blundering movement and sudden flight – much unlike the normal, stealthy night-rhythms of the forest. Only the bear slept on, unmoved as a rock in the sea, hearing nothing, scenting nothing, not feeling even the burns which had destroyed great patches of its pelt and shrivelled the flesh beneath.

With dawn the light wind returned, and brought with it from across the river the smell of mile upon mile of ashes and smouldering jungle. The sun, rising behind the ridge, left in shadow the forest below the western slope. Here the fugitive animals remained, skulking and confused, afraid to venture into the brilliant light now glittering along the shores of the island.

It was this sunshine, and the all-pervading smell of the charred trees, which covered the approach of the man. He came wading knee-deep through the shallows, ducking his head to remain concealed below the feathery plumes of the reeds. He was dressed in breeches of coarse cloth and a skin jerkin roughly stitched together down the sides and across the shoulders. His feet were laced round the ankles into bags of skin resembling ill-shaped boots. He wore a necklace of curved, pointed teeth, and from his belt hung a long knife and a quiver of arrows. His bow, bent and strung, was carried round his neck to keep the butt from trailing in the water. In one hand he was holding a stick on which three dead birds – a crane and two pheasants – were threaded by the legs.

As he reached the shadowed, western end of the island he paused, raised his head cautiously and peered over the reeds into the woods beyond. Then he began to make his way to shore, the reeds parting before him with a hissing sound like that of a scythe in long grass. A pair of duck flew up but he ignored them, for he seldom or never risked the loss of an arrow by shooting at birds on the wing. Reaching dry ground, he at once crouched down in a tall clump of hemlock.

Here he remained for two hours, motionless and watchful, while the sun rose higher and began to move round the shoulder of the hill. Twice he shot, and both arrows found their mark – the one a goose, the other a ketlana, or small forest-deer. Each time he left the quarry lying where it fell and remained in his hiding-place. Sensing the disturbance all around him and himself smelling the ashes on the wind, he judged it best to keep still and wait for other lost and uprooted creatures to come wandering near. So he crouched and watched, vigilant as an Eskimo at a seal-hole, moving only now and then to brush away the flies.

When he saw the leopard, his first movements were no more than a quick biting of the lip and a tightening of his grasp on his bow. It was coming straight towards him through the trees, pacing slowly and looking from side to side. Plainly it was not only uneasy, but also hungry and alert – as dangerous a creature as any solitary hunter might pray to avoid. It came nearer, stopped, stared for some moments straight towards his hiding-place and then turned and padded across to where the kedana lay with the feathered arrow in its neck. As it thrust its head forward, sniffing at the blood, the man, without a sound, crept out of concealment and made his way round it in a half-circle, stopping behind each tree to observe whether it had moved. He turned his head away to breathe and carefully placed each footstep clear of twigs and loose pebbles.

He was already half a bowshot away from the leopard when suddenly a wild pig trotted out of the scrub, blundered against him and ran squealing back into the shadows. The leopard turned, gazed intently and began to pace towards him.

He turned and walked steadily away, fighting against the panic impulse to go faster. Looking round, he saw that the leopard had broken into a padding trot and was overtaking him. At this he began to run, flinging down his birds and making towards the ridge in the hope of losing his terrible pursuer in the undergrowth on the lower slopes. At the foot of the ridge, on the edge of a grove of quian, he turned and raised his bow. Although he knew well what was likely to come of wounding the leopard, it seemed to him now that his only, desperate chance was to try, among the bushes and creepers, to evade it long enough to succeed in shooting it several times and thus either disable it or drive it away. He aimed and loosed, but his hand was unsteady with fear. The arrow grazed the leopard's flank, hung there for a moment and fell out. The leopard bared its teeth and charged, snarling, and the hunter fled blindly along the hillside. A stone turned beneath his foot and he pitched downwards, rolling over and over. He felt a sharp pain as a branch pierced his left shoulder and then the breath was knocked out of him. His body struck heavily against some great, shaggy mass and he lay on the ground, gasping and witless with terror, looking back in the direction from which he had fallen. His bow was gone and as he struggled to his knees he saw that his left arm and hand were red with blood.

The leopard appeared at the top of the steep bank from which he had fallen. He tried to keep silent, but a gasp came from his spent lungs and quick as a bird its head turned towards him. Ears flat, tail lashing, it crouched above him, preparing to spring. He could see its eye-teeth curving downward, and for long moments hung over his death as though over some frightful drop, at the foot of which his life would be broken to nothing.

Suddenly he felt himself pushed to one side and found that he was lying on his back, looking upwards. Standing over him like a cypress tree, one haunch so close to his face that he could smell the shaggy pelt, was a creature; a creature so enormous that in his distracted state of mind he could not comprehend it. As a man carried unconscious from a battlefield might wake bemused and, glimpsing first a heap of refuse, then a cooking-fire, then two women carrying bundles, might tell that he was in a village: so the hunter saw a clawed foot bigger than his own head; a wall of coarse hair, burned and half-stripped to the raw flesh, as it seemed; a great, wedge-shaped muzzle outlined against the sky; and knew that he must be in the presence of an animal. The leopard was still at the top of the bank, cringing now, looking upwards into a face that must be glaring terribly down upon it. Then the giant animal, with a single blow, struck it bodily from the bank, so that it was borne altogether clear, turning over in the air and crashing down among the quian. With a growling roar that sent up a cloud of birds, the animal turned to attack again. It dropped on all fours and as it did so its left side scraped against a tree. At this it snarled and shrank away, wincing with pain. Then, hearing the leopard struggling in the undergrowth, it made towards the sound and was gone.

The hunter rose slowly to his feet, clutching his wounded shoulder. However terrible the transport of fear, the return can be swift, just as one may awaken instantly from deep sleep. He found his bow and crept up the bank. Though he knew what he had seen, yet his mind still whirled incredulously round the centre of certainty, like a boat in a maelstrom. He had seen a bear. But in God's name, what kind of bear? Whence had it come? Had it in truth been already on the island when he had come wading through the shallows that morning; or had it sprung into existence out of his own terror, in answer to prayer? Had he himself perhaps, as he crouched almost senseless at the foot of the bank, made some desperate, phantom journey to summon it from the world beyond? Whether or not, one thing was sure. Whencesoever it had come, this beast, that had knocked a full-grown leopard flying through the air, was now of this world, was flesh and blood. It would no more vanish than the sparrow on the branch.

He limped slowly back towards the river. The goose was gone and his arrow with it, but the kedana was still lying where it had fallen and he pulled out the arrow, heaved it under his good arm and made for the reeds. It was here that the delayed shock overtook him. He sank down, trembling and silently weeping by the water's edge. For a long time he lay prone, oblivious of his own safety. And slowly there came to him – not all at once, but brightening and burning up, littl by little, like a new-lit fire – the realization of what – of who – it must truly be that he had seen.

As a traveller in some far wilderness might by chance pick up a handful of stones from the ground, examine them idly and then, with mounting excitement, first surmise, next think it probable and finally feel certain that they must be diamonds; or as a sea-captain, voyaging in distant waters, might round an unknown cape, busy himself for an hour with the handling of the ship and only then, and gradually, realize that he – he himself – must have sailed into none other than that undiscovered, fabled ocean known to his forbears by nothing but legend and rumour; so now, little by little, there stole upon this hunter the stupefying, all-but-incredible knowledge of what it must be that he had seen. He became calm then, got up and fell to pacing back and forth among the trees by the shore. At last he stood still, faced the sun across the strait and, raising his unwounded arm, prayed for a long time: a wordless prayer of silence and trembling awe. Then, still dazed, he once more took up the ketlana and waded through the reeds. Making his way back along the shallows, he found the raft which he had moored that morning, loosed it and drifted away downstream. 4 The High Baron It was late in the afternoon when the hunter, Kelderek, came at last in sight of the landmark he was seeking, a tall zoan tree some distance above the downstream point of the island. The boughs, with their silver-backed, fern-like leaves, hung down over the river, forming an enclosed, watery arbour inshore. In front of this the reeds had been cut to afford to one seated within a clear view across the strait. Kelderek, with some difficulty, steered his raft to the mouth of the channel, looked towards the zoan and raised his paddle as though in greeting. There was no response, but he expected none. Guiding the raft up to a stout post in the water, he felt down its length, found the rope running shorewards below the surface and drew himself towards land.

Reaching the tree, he pulled the raft through the curtain of pendent branches. Inside, a short, wooden pier projected from the bank and on this a man was seated, staring out between the leaves at the river beyond. Behind him a second man sat mending a net. Four or five other rafts were moored to the hidden quay. The look-out's glance, having taken in the single kedana and the few fish lying beside Kelderek, came to rest upon the weary, blood-smeared hunter himself.

'So. Kelderek Play-with-the-Children. You have little to show and less than usual. Where are you hurt?' 'The shoulder, shendron: and the arm is stiff and painful.' 'You look like a man in a stupor. Are you feverish?' The hunter made no reply. 'I asked, "Are you feverish?" ' He shook his head. 'What caused the wound?'

Kelderek hesitated, then shook his head once more and remained silent,

'You simpleton, do you suppose I am asking you for the sake of gossip? I have to learn everything – you know that. Was it a man or an animal that gave you that wound?' 'I fell and injured myself.' The shendron waited. 'A leopard pursued me,' added Kelderek.

The shendron burst out impatiently. 'Do you think you are telling tales now to children on the shore? Am I to keep asking "And what came next?" Tell me what happened. Or would you prefer to be sent to the High Baron, to say that you refused to tell?'

Kelderek sat on the edge of the wooden pier, looking down and stirring a stick in the dark-green water below. At last the shendron said, 'Kelderek, I know you are considered a simple fellow, with your "Cat Catch a Fish" and all the rest of it. Whether you are indeed so simple I cannot tell. But whether or not, you know well enough that every hunter who goes out has to tell all he knows upon return. Those are Bel-ka-Trazet's orders. Has the fire driven a leopard to Ortelga? Did you meet with strangers? What is the state of the western end of the island? These are the things I have to learn.' Kelderek trembled where he sat but still said nothing.

'Why,' said the net-mender, speaking for the first time, 'you know he's a simpleton – Kelderek Zenzuata – Kelderek Play-with-the-Children. He went hunting – he hurt himself – he's returned with littl to show. Can't we leave it at that? Who wants the bother of taking him up to the High Baron?'

The shendron, an older man, frowned. 'I am not here to be trifled with. The island may be full of all manner of savage beasts; of men, too, perhaps. Why not? And this man you believe to be a simpleton – he may be deceiving us. With whom has he spoken today? And did they pay him to keep silent?'

'But if he were deceiving us,' said the net-mender, 'would he not come with a tale prepared? Depend upon it, he -' The hunter stood up, looking tensely from one to the other.

'I am deceiving no one: but I cannot tell you what I have seen today.'

The shendron and his companion exchanged glances. In the evening quiet, a light breeze set the water clop-clopping under the platform and from somewhere inland sounded a faint call, 'Yasta! The firewood!'

'What is this?' said the shendron. 'You are making difficulties for me, Kelderek, but worse – far worse – for yourself.'

'I cannot tell you what I have seen,' repeated the hunter, with a kind of desperation.

The shendron shrugged his shoulders. 'Well, Taphro, since it seems there's no curing this foolishness, you'd better take him up to the Sindrad. But you are a great fool. Kelderek. The High Baron's anger is a storm that many men have failed to survive before now.' 'This I know. God's will must be done.'

The shendron shook his head. Kelderek, as though in an attempt to be reconciled to him, laid a hand on his shoulder; but the other shook it off impatiently and returned in silence to his watch over the river. Taphro, scowling now, motioned the hunter to follow him up the bank.

The town that covered the narrow, eastern end of the island was fortified on the landward side by an intricate defensive system, part natural and part artificial, that ran from shore to shore. West of the zoan tree, on the further side from the town, four lines of pointed stakes extended from the water-side into the woods. Inland, the patches of diicker jungle formed obstacles capable of little improvement, though even here the living creepers had been pruned and trained into almost impenetrable screens, one behind another. In the more open parts thorn-bushes had been planted – trazada, curlspike and the terrible ancottlia, whose poison burns and irritates until men tear their own flesh with their nails. Steep places had been made steeper and at one point the outfall of a marsh had been damned to form a shallow lake – shrunk at this time of year – in which small alligators, caught on the mainland, had been set free to grow and become dangerous. Along the outer edge of the line lay the so-called 'Dead Belt', about eighty yards broad, which was never entered except by those whose task it was to maintain it. Here were hidden trip-ropes fastened to props holding up great logs; concealed pits filled with pointed stakes – one contained snakes; spikes in the grass; and one or two open, smooth-looking paths leading to enclosed places, into which arrows and other missiles-could be poured from platforms constructed among the trees above. The Belt was divided by rough palisades, so that advancing enemies would find lateral movement difficult and discover themselves committed to emerge at points where they could be awaited. The entire line and its features blended so naturally with the surrounding jungle that a stranger, though he might, here and there, perceive that men had been at work, could form little idea of its full extent. This remarkable closure of an open flank, devised and carried out during several years by the High Baron, Bel-ka-Trazet, had never yet been put to the proof. But, as Bel-ka-Trazet himself had perhaps foreseen, the labour of making it and the knowledge that it was there had created among the Ortelgans a sense of confidence and security that was probably worth as much as the works themselves. The line not only protected the town but made it a great deal harder for anyone to leave it without the High Baron's knowledge.

Kelderek and Taphro, turning their backs on the Belt, made their way towards the town along a narrow path between the hemp fields. Here and there women were carrying up water from among the reeds, or manuring ground already harvested and gleaned. At this hour there were few workers, however, for it was nearly supper time. Not far away, beyond the trees, threads of smoke were curling into the evening sky and with them, from somewhere on the edge of the huts, rose the song of a woman: 'He came, he came by night. I wore red flowers in my hair. I have left my lamp alight, my lamp is burning. Senandril na kora, senandril na ro.'

There was an undisguised warmth and satisfaction in the voice. Kelderek glanced at Taphro, jerked his head in the direction of the song, and smiled. 'Aren't you afraid?' asked Taphro in a surly tone. The grave, preoccupied look returned to Kelderek's eyes.

'To go before the High Baron and say that you persisted in refusing to tell the shendron what you know? You must be mad I Why be such a fool?'

'Because this is no matter for concealment or lying. God -' he broke off.

Taphro made no reply, but merely held out his hand for Kelderek's weapons – knife and bow. The hunter handed them to him without a word.

They came to the first huts, with their cooking, smoke and refuse smells. Men were returning from the day's work and women, standing at their doors, were calling to children or gossiping with neighbours. Though one or two looked curiously at Kelderek trudging acquiescently beside the shendron's messenger, none spoke to him or called out to ask where they were going. Suddenly a child, a boy perhaps seven or eight years old, ran up and took his hand. The hunter stopped. 'Kelderek,' asked the child, 'are you coming to play this evening?'

Kelderek hesitated. 'Why – I can't say. No, Sarin, I don't think I shall be able to come this evening.'

'Why not?' said the child, plainly disappointed. 'You've hurt your shoulder – is that it?'

'There's something I've got to go and tell the High Baron,' replied Kelderek simply. Another, older boy, who had joined them, burst out laughing. 'And I have to see the Lord of Belda before dawn – a matter of life and death. Kelderek, don't tease us. Don't you want to play tonight?'

'Come on, can't you?' said Taphro impatiently, shuffling his feet in the dust.

'No, it's the truth,' said Kelderek, ignoring him. 'I'm on my way to see the High Baron. But I'll be back: either tonight or – well, another night, I suppose.' He turned away, but the boys trotted beside him as he walked on.

'We were playing this afternoon,' said the little boy. 'We were playing "Cat Catch a Fish". I got the fish home twice.' 'Well done' said the hunter, smiling down at him.

'Be off with you!' cried Taphro, making as though to strike at them. 'Come on – get out!' You great dunder-headed fool,' he added to Kelderek, as the boys ran off. 'Playing games with children at your age!'

'Good night!' called Kelderek after them. 'The good night you pray for – who knows?'

They waved to him and were gone among the smoky huts. A man passing by spoke to Kelderek but he made no reply, only walking on abstractedly, his eyes on the ground.

At length, after crossing a wide area of rope-walks, the two approached a group of larger huts standing in a rough semi-circle not far from the eastern point and its broken causeway. Between these, trees had been planted, and the sound of the river mingled with the evening breeze and the movement of the leaves to give a sense of refreshing coolness after the hot, dry day. Here, not only women were at work. A number of men, who seemed by their appearance and occupations to be both servants and craftsmen, were trimming arrows, sharpening stakes and repairing bows, spears and axes. A burly smith, who had just finished for the day, was climbing out of his forge in a shallow, open pit, while his two boys quenched the fire and tidied up after him. Kelderek stopped and turned once more to Taphro.

'Badly-aimed arrows can wound innocent men. There's no need for you to be hinting and gossiping about me to these fellows.' 'Why should you care?' 'I don't want them to know I'm keeping a secret,' said Kelderek.

Taphro nodded curdy and went up to a man who was cleaning a grindstone, the water flying off in a spiral as he spun the wheel. 'Shendron's messenger. Where is Bel-ka-Trazet?'

'He? Eating.' The man jerked his thumb towards the largest of the huts. 'I have to speak to him.'

'If it'll wait,' replied the man, 'you'd do better to wait Ask Numiss – the red-haired fellow – when he comes out. He'll let you know when Bel-ka-Trazet's ready.'

Neolithic man, the bearded Assyrian, the wise Greeks, the howling Vikings, the Tartars, the Aztecs, the samurai, the cavaliers, the anthropophagi and men whose heads do grow beneath their shoulders: there is one thing at least that all have known in common – waiting until someone of importance has been ready to see them. Numiss, chewing a piece of fat as he listened to Taphro, cut him short, pointing him and Kelderek to a bench against the wall. There they sat. The sun sank until its rim touched the horizon upstream. The flies buzzed. Most of the craftsmen went away. Taphro dozed. The place became almost deserted, until the only sound above that of the water was the murmur of voices from inside the big hut. At last Numiss came out and shook Taphro by the shoulder. The two rose and followed the sen-ant through the door, on which was painted Bel-ka-Trazet's emblem, a golden snake.

The hut was divided into two parts. At the back were Bel-ka-Trazet's private quarters. The larger part, known as the Sindrad, served as both council-chamber and mess-hall for the barons. Except when a full council was summoned it was seldom that all the barons were assembled at once. There were continual journeys to the mainland for hunting expeditions and trade, for the island had no iron or other metal except what could be imported from the Gelt mountains in exchange for skins, feathers, semi-precious stones and such artifacts as arrows and rope; whatever, in fact, had any exchange value. Apart from the barons and those who attended upon them, all hunters and traders had to obtain leave to come and go. The barons, as often as they returned, were required to report their news like anyone else and while living on the island usually ate the evening meal with Bel-ka-Trazet in the Sindrad.

Some five or six faces turned towards Taphro and Kelderek as they entered. The meal was over and a debris of bones, rinds and skins littered the floor. A boy was collecting this refuse into a basket, while another sprinkled fresh sand. Four of the barons were still sitting on the benches, holding their drinking-horns and leaning their elbows on the table. Two, however, stood apart near the doorway – evidently to get the last of the daylight, for they were talking in low tones over an abacus of beads and a piece of smooth bark covered with writing. This seemed to be some kind of list or inventory, for as Kelderek passed, one of the two barons, looking at it, said, 'No, twenty-five ropes, no more,' whereupon the other moved back a bead with his fore-finger and replied, 'And you have twenty-five ropes fit to go, have you?'

Kelderek and Taphro came to a stop before a young, very tall man, with a silver torque on his left arm. When they entered he had had his back to the door, but now he turned to look at them, holding his horn in one hand and sitting somewhat unsteadily on the table with his feet on the bench below. He looked Kelderek up and down with a bland smile, but said nothing. Confused, Kelderek lowered his eyes. The young baron's silence continued and the hunter, by way of keeping himself in countenance, tried to fix his attention on the great table, which he had heard described but never before seen. It was old, carved with a craftsmanship beyond the skill of any carpenter or woodworker now alive on Ortelga. Each of the eight legs was pyramidal in shape, its steeply-tapering sides forming a series of steps or ledges, one above another to the apex. The two corners of the board that he could sec had the likeness of bears' heads, snarling, with open jaws and muzzles thrust forward. They were most life-like. Kelderek trembled and looked quickly up again.

'And what ekshtra work you come give us?' asked the young baron cheerfully. 'Want fellows repair causeway, zattit?'

'No, my lord,' said Numiss in a low voice. 'This is the man who refused to tell his news to the shendron.'

'Eh?' asked the young baron, emptying his horn and beckoning to a boy to re-fill it. 'Man with shensh, then. No ushe talking shendrons. Shtupid fellowsh. All shendrons shtupid fellowsh, eh?' he said to Kelderek.

'My lord,' replied Kelderek, 'believe me, I have nothing against the shendron, but – but the matter 'Can you read?' interrupted the young baron. 'Read? No, my lord.'

'Neither c'n I. Look at old Fassel-Hasta there. What's he reading? Who knows? You watch out; he'll bewitch you.'

The baron with the piece of bark turned with a frown and stared at the young man, as much as to say that he at any rate was not one to act the fool in his cups.

'I'll tell you,' said the young baron, sliding forward from the table and landing with a jolt on the bench, 'all 'bout writing – one word -'

'Ta-Kominion,' called a harsh voice from the further room, 'I want to speak with those men. Zelda, bring them.'

Another baron rose from the bench opposite, beckoning to Kelderek and Taphro. They followed him out of the Sindrad and into the room beyond, where the High Baron was sitting alone. Both, in token of submission and respect, bent their heads, raised the palms of their hands to their brows, lowered their eyes and waited.

Kelderek, who had never previously come before Bel-ka-Trazet, had been trying to prepare himself for the moment when he would have to do so. To confront him was in itself an ordeal, for the High Baron was sickeningly disfigured. His face – if face it could still be called – looked as though it had once been melted and left to set again. Below the white-seamed forehead the left eye, askew and fallen horribly down the cheek, was half buried under a great, humped ridge of flesh running from the bridge of the nose to the neck. The jaw was twisted to the right, so that the lips closed crookedly; while across the chin stretched a livid scar, in shape roughly resembling a hammer. Such expression as there was upon this terrible mask was sardonic, penetrating, proud and detached -that of a man indestructible, a man to survive treachery, siege, desert and flood.

The High Baron, seated on a round stool like a drum, stared up at the hunter. In spite of the heat he was wearing a heavy fur cloak, fastened at the neck with a brass chain, so that his ghastly head resembled that of an enemy severed and fixed on top of a black tent. For some moments there was silence – a silence like a drawn bow-string. Then Bel-ka-Trazet said, 'What is your name?'

His voice, too, was distorted; harsh and low, with an odd ring, like the sound of a stone bounding over a sheet of ice. 'Kelderek, my lord.' 'Why are you here?' 'The shendron at the zoan sent me.' 'That I know. Why did he send you?' 'Because I did not think it right to tell him what befell me today.'

'Why does your shendron waste my time?' said Bel-ka-Trazet to Taphro. 'Could he not make this man speak? Are you telling me he defied you both? '

'He – the hunter – this man, my lord,' stammered Taphro. 'He told us – that is, he would not tell us. The shendron – he asked him about – about his injury. He replied that a leopard pursued him, but he would tell us no more. When we demanded to know, he said he could tell us nothing.' There was a pause. 'He refused us, my lord,' persisted Taphro. 'We said to him -' 'Be silent.'

Bel-ka-Trazet paused, frowning abstractedly and pressing two fingers against the ridge beneath his eye. At length he looked up.

'You are a clumsy liar, Kelderek, it seems. Why trouble to speak of a leopard? Why not say you fell out of a tree?' 'I told the truth, my lord. There was a leopard.'

'And this injury,' went on Bel-ka-Trazet, reaching out his hand to grasp Kelderek's left wrist, and gently moving his arm in a way that suggested that he might pull it a good deal harder if he chose, 'this trifling injury. You had it, perhaps, from someone who was disappointed that you had not brought him better news? Perhaps you told him, "The shendrons are alert, surprise would be difficult," and he was displeased?' 'No, my lord.'

'Well, we shall see. There was a leopard, then, and you fell. What happened then?' Kelderek said nothing. 'Is this man a half-wit?' asked Bel-ka-Trazet, turning to Zelda.

'Why, my lord,' replied Zelda, 'I know little of him, but I believe he is known for something of a simple fellow. They laugh at him – he plays with the children -' 'He does what?' 'He plays with children, my lord, on the shore.' 'What else?'

'Otherwise he is solitary, as hunters often are. He lives alone and harms no one, as far as I know. His father had hunter's rights to come and go and he has been allowed to inherit them. If you wish, we can send to find out more.' 'Do so,' said Bel-ka-Trazet: and then to Taphro, 'You may go.'

Taphro snatched his palm to his forehead and was gone like a candle-flame in the wind. Zelda followed him with more dignity.

'Now, Kelderek,' said the twisted mouth, slowly, 'you are an honest man, you say, and we are alone, so there is nothing to hinder you from telling your story.'

Sweat broke out on Kelderek's face. He tried to speak, but no words came.

'Why did you tell the shendron a few words and then refuse to tell more?' said the High Baron. 'What foolishness was that? A rogue should know how to cover his tracks. If there was something you wished to conceal, why did you not invent some tale that would satisfy the shendron?'

'Because – because the truth – ' The hunter hesitated. 'Because I was afraid and I am still afraid.' He stopped, but then burst out suddenly, 'Who can lie to God? – ' Bel-ka-Trazet watched him as a lizard watches a fly. ' Zelda P he called suddenly. The baron returned.

'Take this man out, put his arm in a sling and let him eat Bring him back in half an hour – and then, by this knife, Kelderek -' and he drove the point of his dagger into the golden snake painted on the lid of the chest beside him – 'you shall tell me what you know.'

The unpredictable nature of dealings with Bel-ka-Trazet were the subject of many a tale. With Zelda's hand under his shoulder, Kelderek stumbled out into the Sindrad and sat huddled on a bench while the boys brought him food and a leather sling.

When next he faced Bel-ka-Trazet night had fallen. The Sindrad outside was quiet, for all but two of the barons had gone to their own quarters. Zelda sat in the firelight, looking over some arrows which the fletcher had brought Fassel-Hasta was hunched on another bench at the table, slowly writing, with an inked brush on bark, by the light of a smoky earthenware lamp. A lamp was burning also on the lid of Bel-ka-Trazet's chest. In the shadows beyond, two fire-flies went winking about the room. A curtain of wooden beads had been let fall over the doorway and from time to time these clicked quietly in the night breeze.

The distortion of Bel-ka-Trazet's face seemed like a trick of the lamplight, the features monstrous as a devil-mask in a play, the nose appearing to extend to the neck in a single, unbroken line, the shadows under the jaw pulsing slightly and rhythmically, like the throat of a toad. And indeed it was a play they were now to act^ thought Kelderek, for it accorded with nothing in life as he had known it A plain man, seeking only his living and neither wealth nor power, had been mysteriously singled out and made an instrument to cross the will of Bel-ka-Trazet

'Well, Kelderek,' said the High Baron, pronouncing his name with a slight emphasis that somehow conveyed contempt, 'while you have been filling your belly, I have learned as much as there is to be known about a man like you – all, that is, but what you are going to tell me now, Kelderek Zenzuata. Do you know they call you that?* 'Yes, my lord.'

'Kelderek Play-with-the-Children. A solitary young man, with no taste for taverns, it seems, and an unnatural indifference towards girls: but known nevertheless for a skilful hunter, who often brings in game and rarities for the factors trading with Gelt and Bekla.' 'If you have heard so much, my lord -'

'So that he is allowed to come and go alone, much as he pleases, with no questions asked. Sometimes he is gone for several days at a time, is he not?' 'It is necessary, my lord, if the game – 'Why do you play with the children? A young man unmarried – what sort of nonsense is that?' Kelderek considered.

'Children often need friends,' he said. 'Some of the children I play with are unhappy. Some have been left with no parents – their parents have deserted them -'

He broke off in confusion, meeting the gaze of Bel-ka-Trazet's distorted eye over the ridge. After some minutes he muttered uncertainly, 'The flames of God -' 'What? What did you say?'

'The flames of God, my lord. Children – their eyes and ears are still open – they speak the truth -'

'And so shall you, Kelderek, before you are done. You'd be thought a simple fellow, then, soft in the head perhaps, a stranger to drink and wenches, playing with children and given to talk of God; for no one would suspect such a man, would he, of spying, of treachery, of carrying messages or treating with enemies on his lonely hunting expeditions -' 'My lord -'

'Until one day he returns injured and almost empty-handed from a place believed to be full of game, too much confused to have been able to invent a tale -' 'My lord!' The hunter fell on his knees.

'Did you displease the man, Kelderek, was that it? Some brigand from Deelguy, perhaps, or slimy slave-trader from Terekenalt out to make a little extra money by carrying messages during his dirty travels? Your information was displeasing, perhaps, or the pay was not enough?' 'No, my lord, no!' 'Stand up!'

The beads clicked in a gust that flattened the lamp-flame and made the shadows dart on the wall like fish startled in a deep pool. The High Baron was silent, collecting himself with the air of a man repulsed by an obstacle but still determined to overcome it by one means or another. When he spoke again it was in a quieter tone.

'Well, so far as I am any judge, Kelderek, you may be an honest man, though you are a great fool with your talk of children and God. Could you not have asked for one single friend to come here, to testify to your honesty?' 'My lord -'

'No, you could not, it seems, or else it never occurred to you. But let us assume that you are honest, and that something took place today which for some reason you have neither concealed nor revealed. If you had gone about with ginning to conceal it altogether, I suppose you would not have been compelled to come here – you would not be standing here now. No doubt, then, you know very well that it is something that is bound to come to light sooner or later, so that it would have been foolish for you to try to hide it.'

'Yes, I am sure enough of that, my lord,' replied Kelderek without hesitation.

Bel-ka-Trazet drew his knife and, like a man idly passing the time while waiting for supper or a friend, began to heat the point in the lamp-flame.

'My lord,' said Kelderek suddenly, 'if a man were to return from hunting and say to the shendron, or to his friends, "I have found a star, fallen from the sky to the earth," who would believe him?'

Bel-ka-Trazet made no reply, but went on turning the point of the knife in the flame.

'But if that man had indeed found a star, my lord, what then? What should he do and to whom should he bring it?'

'You question me, and in riddles, Kelderek, do you? I have no love for visionaries or their talk, so be careful.'

The High Baron clenched his fist but then, like a man determined to exercise patience, let it fall open and remained staring at Kelderek with a sceptical look. 'Well?' he said at length.

'I fear you, my lord. I fear your power and your anger. But the star that I found – it is from God, and this, too, I fear. I fear it more. I know to whom it must be revealed -' his voice came in a strangled gasp – 'I can reveal it – only to the Tuginda!'

In an instant Bel-ka-Trazet had seized him by the throat and forced him to the floor. The hunter's head bent sharply backwards, away from the hot knife-point thrust close to his face.

'I will do this -1 can do only that! By the Bear, you will no longer choose what you will do when your bow-eye is out! You'll end in Zeray, my child!'

Kelderek's hands stretched upwards, clutching at the black cloak bending over him and pressing him backwards from knee to wounded shoulder. His eyes were closed against the heat of the knife and he seemed about to faint in the High Baron's grasp. Yet when at length he spoke – Bel-ka-Trazet stooping close to catch the words – he whispered, 'It can be only as God wills, my lord. The matter is great -greater, even, than your hot knife.' The beads clashed in the doorway. Without relinquishing his hold the Baron peered over his shoulder into the gloom beyond the lamp. Zelda's voice said,

'My lord, there are messengers from the Tuginda. She would speak with you urgently, she says. She requests that you go to Quiso tonight.'

Bel-ka-Trazet drew in his breath with a hiss and stood straight, shaking off Kelderek, who fell his length and lay without moving. The knife slipped from the High Baron's hand and stuck in the floor, transfixing a fragment of some greasy rubbish, which began to smoulder with an evil smell. He stooped quickly, recovered the knife and trod out the fragment. Then he said quietly,

'To Quiso, tonight? What can this mean? God protect us! Are you sure?'

'Yes, my lord. Would you speak yourself with the girls who brought the message?'

'Yes – no, let it be. She would not send such a message unless -Go and tell Ankray and Faron to get a canoe ready. And see that this man is put aboard.' 'This man, my lord?' 'Put aboard.'

The bead curtain clashed once more as the High Baron passed through it, across the Sindrad and out among the trees beyond. Zelda, hurrying across to the servants' quarters, could sec in the light of the quarter moon the conical shape of the great fur cloak striding impatiently up and down the shore. 5 To Quiso by Night Kelderek knelt in the bow, now peering into the speckled gloom ahead, now shutting his eyes and dropping his chin on his chest in a fresh spasm of fear. At his back the enormous Ankray, Bel-ka-Trazet's servant and bodyguard, sat silent as the canoe drifted with the current along the south bank of the Telthearna. From time to time Ankray's paddle would drop to arrest or change their course, and at the sound Kelderek started as though the loud stir of the water were about to reveal them to enemies in the dark. Since giving the order to set out Bel-ka-Trazet had said not a word, sitting hunched in the narrow stern, hands clasped about his knees. More than once, as the paddles fell, the swirl and seethe of bubbles alarmed some nearby creature, and Kelderek jerked his head towards the clatter of wings, the splash of a dive or the crackle of undergrowth on the bank. Biting his lip and clutching at the side of the canoe, he tried to recall that these were nothing but birds and animals with which he was familiar – that by day he would recognize each one. Yet beyond these noises of flight he was listening always for another, more terrible sound and dreading the second appearance of that animal to whom, as he believed, the miles of jungle and river presented no obstacle. And again, shrinking from this, his mind confronted dismally another life-long fear – the fear of the island for which they were bound. Why had the Baron been summoned thither and what had that summons to do with the news which he himself had refused to tell?

They had already travelled a long way beneath the trees overhanging the water, when the servants evidently recognized some landmark. The left paddle dropped once more and the canoe checked, turning towards the centre of the river. Upstream, a few faint lights on Ortelga were just visible, while to their right, far out in the darkness, there now appeared another light, high up; a flickering, red glow that vanished and re-emerged as they moved on. The servants were working now, driving the canoe across the stream while the current, flowing more strongly at this distance from the bank, carried them down. Kelderek could sense in those behind him a growing uneasiness. The paddlers' rhythm became short and broken. The bow struck against something floating in the dark, and at the jolt Bel-ka-Trazet grunted sharply, like a man on edge. 'My lord -' said Ankray. 'Be silent!' replied Bel-ka-Trazet instantly.

Like children in a dark room, like wayfarers passing a graveyard at night, the four men in the canoe filled the surrounding darkness with the fear from their own hearts. They were approaching the island of Quiso, domain of the Tuginda and the cult over which she ruled, a place where men retained no names – or so it was believed – weapons had no effect and the greatest strength could spend itself in vain against incomprehensible power. On each fell a mounting sense of solitude and exposure. To Kelderek it seemed that he lay upon the black water helpless as the diaphanous gylon fly, whose fragile myriads clotted the surface of the river each spring; inert as a felled tree in the forest, as a log in the timber-yard. All about them, in the night, stood the malignant, invisible woodmen, disintegrators armed with axe and fire. Now the log was burning, breaking up into sparks and ashes, drifting away beyond the familiar world of day and night, of hunger, work and rest. The red light seemed close now, and as it drew nearer still and higher above them he fell forward, striking his forehead against the bow.

He felt no pain from the blow; and to himself he seemed to have become deaf, for he could no longer hear the lapping of the water. Bereft of perceptions, of will and identity, he knew himself to have become no more than the fragments of a man. He was no one; and yet he remained conscious. As though in obedience to a command, he closed his eyes. At the same moment the paddlers ceased their stroke, bowing their heads upon their arms, and the canoe, losing way entirely, drifted with the current towards the unseen island.

Now into the remnants of Kelderek's mind began to return all that, since childhood, he had seen and.learned of the Tuginda. Twice a year she came to Ortelga by water, the far-off gongs sounding through the mists of early morning, the people waiting silent on the shore. The men lay flat on their faces as she and her women were met and escorted to a new hut built for her coming. There were dances and a ceremony of flowers: but her real business was first, to confer with the barons and secondly, in a session secret to the women, to speak of their mysteries and to select, from among those put forward, one or two to return with her to perpetual service on Quiso. At the end of the day, when she left in torchlight and darkness, the hut was burned and the ashes scattered on the water.

When she stepped ashore she was veiled, but in speaking with the barons she wore the mask of a bear. None knew the face of the Tuginda, or who she might once have been. The women chosen to go to her island never returned. It was believed that there they received new names; at all events their old names were never spoken again in Ortelga. It was not known whether the Tuginda died or abdicated, who succeeded her, how her successor was chosen, or even, on each occasion of her visit, whether she was, in fact, the same woman as before. Once, when a boy, Kelderek had questioned his father with impatience, such as the young often feel for matters which they perceive that their elders regard seriously and discuss little. For reply his father had moistened a lump of bread, moulded it to the rough shape of a man and put it to stand on the edge of the fire. 'Keep away from the women's mysteries, lad,' he said, 'and fear them in your heart, for they can consume you. Look the bread dried, browned, blackened and shrivelled to a cinder – 'do you understand?' Kelderek, silenced by his father's gravity, had nodded and said no more. But he had remembered.

What had possessed him, tonight, in the room behind the Sindrad? What had prompted him to defy the High Baron? How had those words passed his lips and why had not Bel-ka-Trazet killed him instantly? One thing he knew – since he had seen the bear, he had not been his own master. At first he had thought himself driven by the power of God, but now chaos was his master. His mind and body were unseamed like an old garment and whatever was left of himself lay in the power of the numinous, night-covered island.

His head was still resting on the bow and one arm trailed overside in the water. Behind him, the paddle dropped from Ankray's hands and drifted away, as the canoe grounded on the upstream shore, its occupants slumped where they sat, tranced and spell-stopped, not a will, not a mind intact. And thus they stayed, driftwood, flotsam and foam, while the quarter moon set far upstream and darkness fell, broken only by the gleam of the fire still burning inland, high among the trees.

Time passed – a time marked only by the turning of the stars. Small, choppy river-waves chattered along the sides of the canoe and once or twice, with a rising susurration, the night wind tossed the branches of the nearest trees: but never the least stir made the four men in the canoe, huddled in the dark like birds on a perch.

At length a nearer, smaller light appeared, green and swaying, descending towards the water. As it readied the pebbly shore there sounded a crunching of footsteps and a low murmur of voices. Two cloaked women were approaching, carrying between them, on a pole, a round, flat lantern as big as a grindstone. The frame was of iron and the spaces between the bars were panelled with plaited rushes, translucent yet stout enough to shield and protect the candles fixed within.

The two women reached the edge of the water and stood listening. After a little they perceived in the dark the knock of the water against the canoe – a sound distinguishable only by ears familiar with every cadence of wind and wave along the shore. They set down the lantern then, and one, drawing out the pole from the ring and splashing it back and forth in the shallows, called in a harsh voice, 'Wake!'

The sound came to Kelderek sharp as the cry of a moorhen. Looking up, he saw the wavering, green light reflected in the splashed water inshore. He was no longer afraid. As the weaker of two dogs presses itself to the wall and remains motionless, knowing that in this lies its safety, so Kelderek, through total subjection to the power of the island, had lost his fear.

He could hear the High Baron stirring behind him. Bel-ka-Trazet muttered some inaudible words and dashed a handful of water across his face, yet made no move to wade ashore. Turning his head for a

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |