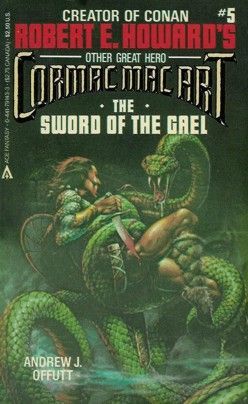

"The Sword of the Gael" - читать интересную книгу автора (Offutt Andrew J)

|

Andrew J Offutt

The Sword of the Gael

Foreword

This novel is the result of a couple of love affairs.

To begin with, I have been a fan of the work of Robert E. Howard for a long time. I don’t expect to “outgrow” that, and Cormac son of Art of Connacht is a Howard character.

Next, while reading over a million words in research and taking thousands of words of notes, I fell hopelessly in love with the Emerald Isle, whether it be called Eirrin or Erin or Eire or Ireland. That me grandmither was an O’Driscoll has nothing to do with it-I think. Nor even-I think-that I once married a woman whose name strings out as Mary Josephine McCarney McCabe Offutt. Or maybe that’s O’ffutt…

It is astonishing how little we know of history or “history,” other than Roman, before AD 800 or so. Open your encyclopedia to Scotland or Ireland or any part of Britain and see when they seem to think history began. Even at that I was unable to get hold of all the material I needed (whether I knew of its existence or not), and shall as a consequence probably catch it from some of the Eirrin-born.

Consider this: Stirrups had not been invented at the time of this novel (about AD 490). Stirrups made possible chivalry (from

Some will note that the history shown here is accurate-but that the history books show different royal names in the late fifth century. This is

But I think that belongs in an article I will probably write, some day. Meanwhile: Things are not always as they seem, even when we have “historical records.” (Tell me about a contemporary-?-of Cormac, King Arthur, and then go look him up. The Mayaguez incident of modern piracy is history, and we can lay it all out neatly from start to finish-or can we?)

Finally there is this.

I have avowed being a fan of Robert E. Howard; we even collect

Nevertheless, I have not attempted to copy Howard. Where is the worthiness in that?

Howard was like Burroughs in that people can and do make themselves feel superior by making fun of his cardboard characters and purple prose. (Building oneself up by tearing others down is a favorite game-because it is so easy.) Yet, like that of Burroughs, Howard’s work lives and has grown increasingly more popular. Simply put, REH, like ERB, had the Magic. Whether we are fans or imitators-there are lots of those-or emulators or choke-gasp critics, we all sort of wish we had that Magic, too. If I’ve got hold of some of it, wonderful! You can pat my back if you’re of a mind to and my hand will be right there with yours.

In addition, though, I was completely charmed by the language of Augusta Gregory’s 1892 translation of the great Irish folk-cycle,

That’s enough. All I started off to do was tell you about the lack of stirrups, and what a great joy and sheer

Maybe the publisher will let me write another Cormac story. It’s fun.

andrew j offutt

Kentucky, U.S.A.

April, 1975

– from “Cormac the Gael,”

by Ceann Ruadh, the “Minstrel-king”

– Prayer of the poet Amergin for the coming of the Celts to Eire

Like a demon from the darkest Plutonian hell of the fallen Romans, the wind shrieked and howled in its sudden attack.

It was a vicious wild thing bent on the destruction of sailcloth and timber and human flesh, and men of the

The deckless little ship spun and careened. Its single mast was cracked and had fallen, to carry with it two good men amid striped squaresail of Nordic weave. Down went

The hugest of those desperate seafarers held fast the jagged stump of the ruined mast. To his great broad swordbelt clung one of his men; to his knotty calf in its soaked leggings hung another, fearful of being swept off the ridge of the world. The huge man gripped the mast as though it was his beloved. He it was who bellowed out to Father Odin and his son The Thunderer, for they had escaped the dread whirlpool off these nameless little isles of unpredictable elements only to fall prey to this demon-shrieking gale.

One-eyed Odin and his son heard not-or if they did, were steadfast in their resolve to punish their sometime servant for his many sins. Nor durst he relinquish his grip even so long as to draw steel, that he might die as befit his people, with sword in ruddy fist.

The little ship spun, swung, tipped, and spun again. It hurtled headlong. Islands flew by, shod and crowned with jagged rock. Cordage creaked and wood groaned as if in mortal agony. Men moaned, or prayed, or shouted-or screamed and went to their fathers.

One among their number was silent, and him alone.

He was a man apart in other ways, his armour different and his hair a swatch of the midnight sky. Grim, stolid with the insouciance of a fighting man who expects neither reward nor punishment but takes what may come from gods and men, his mouth was tightpressed and his scarred face almost impassive. He had nailed himself to the dying craft with his own great sword.

Full two inches into the ship’s wood just aft of the dragon headed prow he had driven that oft-gored blade. Around its hilt he had secured his swordbelt, and to belt and gunwale he clung, with hands like the vises in a smith’s smoky domain.

This man’s slitted eyes were grey as the steel of the blade by which he bound himself aboard. In those eyes there was no fear, no horror-nor yet acceptance, either. Only a certain sadness as his Danish companions died for nought but god-whim, and a waiting. He remained alert and ready to release his iron handed grips and hurl himself into those waves like walls, should the craft break or be driven down into airless realms.

Between two craggy little isles no bigger than the dun-keeps of rich men the frail craft was swept.

Rocky walls rushed by. Instantly the force of the dread gale was quartered by intervening granite. Ten men, left of nineteen, heaved sighs of relief-

But

“Ah, NO!” a man cried out, and his nails dug into the ship’s seasoned timber so that the fingers bled. “Pray to your people’s sea-god, Gael! It’s in his domain we’re wind-captured, sure, not the All-father’s!”

The grey-eyed man regarded him without change in his set features. He recalled the seagod of the blue-hilled land he’d long since left, a fugitive. His lips formed that ancient name, though not in prayer, for this descendant of Milesian Celts begged of neither human nor immortal.

And then his teeth clamped, hard, for the ship was dashed against the offshore rocks of another isle and wind-rammed up an unknown beach, and

Strong men flew like dolls clad in glittering steel onto that nameless shore, and were still.

The wind relented and returned to whatever dark lair housed it between the times it drove howling forth to express contempt and hatred for the sons of men.

Like new gold a summer sun burst its cloud-bonds. Sand sparkled on the strand of an unknown island well off the southwestern coast of abandoned Britain. Wind-driven water vanished in vapourous shimmers and the sand paled as it dried. The airy shimmer hovered, too, above the forms of nine prostrate men. Prone or supine or pitifully curled, they lay strewn along the shore where they’d been flung.

The scales and links of battle-scarred armour dried, and heated in the sun. Prostrate men sent back a steely scintillance.

Nine men, lying still.

All were flaxen or red of hair, save the one whose dark mane tumbled from beneath his scarred helmet. All wore armour of good scale mail, save only that one, whose chainmail was forged and linked in the way of Eirrin and Alba to the northeast. All were believers in and followers of One-eyed Odin and his hammer-wielding son Thor or Thunor-save only that one, whose superstitions lay with those of the Druids: The Sidhe of green-cloaked Eirrin, and Agron and Scathach, Grannus and Morrigu the Battle Crow and cu Roi mac Dairi, and Behl of the sun for whom burned the Behl-fires… and great Crom, god of an Eirrin older even that Behl’s power.

All, too, were of the cold land of the Danes, save only that one, and he of Eirrin-and an exile.

It was he who first awoke.

The Gael wakened to the familiar salt scent of the sea. A gull screeked. Lying still, the black-haired man twitched his nostrils in the manner of a wary wolf. He scented nothing of that which was all too familiar-raw, blood. Blinking against the flaming sun and the lingering grogginess of unconsciousness, he squinted open his eyes.

“Blood of the gods,” he muttered. “This be no afterworld, surely-I live!”

Slowly, alert to the flashing pain of broken limb or back or neck, he sat up. There was no flash, but only twinges from a body badly used by the wind. He was whole. Those twinges might have brought moans and lamentations and supine confinement to other men. To him, they were but the boon companions of weapon-men. He was whole; it was enough.

He looked about.

Strewn around him were his companions, lying as they had fallen along a stretch of beach that would have enclosed the house of one of those self-proclaimed “kings” of Britain since the Romans left. A tiny smile tugged at his mouth when he saw the rise and fall of the great barrel that was the chest of Wulfhere Skull-splitter. The giant lived also. Slitted eyes roved; assured their owner that so did all breathe-though there were but seven others.

Before the gale, they had been one and twenty.

He swallowed. There was thirst on him. With a grunt he rose, saw the gleam of his sword, and retrieved it. He wiped it again and again on his sun-hot trews before returning it to the sand; a watery sheath was no more trustworthy than a crowned man.

As he unbuckled belt with pendent sheaths, he looked around himself the more.

Of their ship there was no sign.

The sweet sandy shore was a lie. This was a barren and inhospitable speck on the waters, and it would offer little comfort to man or beast. Only the fowls could come and go at will, for aye there were ugly-voiced gulls, and he heard the honk of wild ducks or geese.

And all around: stone. Granite and basalt, igneous rock like petrified sponge, and the sand to which some of it had been worn, by wind and sea with the aid of uncaring time.

He saw how the beach ran up bare and desolate, strewn with drifts and gravel and fragments of rock. Then rose, towering, steep and gloomy ramparts of natural rock, deep-hued basalt. Its somberness was cut here and there with veins of paler lipartite and studded with twinkling quartz, set like jewels against the dark and brooding background.

The Gael compressed his lips. The island was like a great rock wall or giant’s castle, surrounded by shore and a coast that was mostly rocky and precipitous, and then by an enormous protective moat: the domain of Manannan MacLir, the unending sea.

Then a voice rumbled up from a massy chest. “There’s a great drouth in my throat. If this be Valhalla, where be the cup-bearers?”

The Gael was forced to chuckle. He turned to look at the big man, Wulfhere Hausakliufr, who was in the act of sitting up. Already he scratched in his beard:

“I see no cup-bearers, and a Valkyrie I am not, bush-face.”

Wulfhere looked at him. “Cormac! We live!”

The Gael nodded. “We do. And all others breathe.”

Even as he spoke, another stirred. Like Wulfhere, he scratched at the salt encrusting his chin deep within his vermilion beard. “Where are we?”

Wulfhere’s reply was a snort. “Ask the gulls, Ivarr.”

The Gael named Cormac said, “Where are we? Here.”

Ivarr sighed, twisted, shoved himself erect with a palm against the sand. He gazed around himself.

“Ugh and och!

“Ahh… methinks my arm be broke.”

“You are lying on it, Guthrum,” Cormac told that waking Dane. “Stir yourself. It’s a nice sleep we’ve had: the little death. An we find not water, and that soon, it will be the big sleep on us all.”

Another man moved, with first a grunt and then a curse. “Water! Hmp-it’s

Cormac was removing his sleeveless tunic of linked chain. “Food!

“Arrgh,” Halfdan Half-a-man growled, and he made a face.

“-and wild geese or ducks,” the man of Eirrin went on. “And it’s their blood we’ll be drinking, Wulfhere, and proclaiming it the fairest quencher of thirst on the ridge of the world!”

On his feet, Wulfhere poked a finger into his scarlet beard to scratch. He nodded, a giant with breast muscles that bulged like a brace of shields beneath his corselet of scalemail. He grunted when he stooped for his horned helmet. With that on his head he was even more formidable and giant-like.

“Ummm,” he agreed in a rumbling grumble. “We shall not die of thirst or starvation, then. And meanwhile-what do we

“Care for our armour,” Cormac advised. With his removed, he folded his legs and lowered himself to the sand. He commenced a meticulous wiping of each of the many links of good small chain, to rid it of salt and rust-bringing water.

Thirst and rumbling bellies were ignored as one, then three, and at last eight others followed his example. A man could stand his hunger and his dry throat. Arms and armour, though-on those his life depended. Despite the fact that this island was surely abandoned by the gods, and unpeopled by the sons of man so that it might be home now in both life and death, the nine survivors of

As he had begun first and had no scales to lift, it was Cormac who first finished and rose. As though he might at any instant meet an army of attackers, he doggedly fastened armour and arms about his lean, rangy form. Wulfhere glanced up.

“Whither?”

“You’ve more armour to see to,” Cormac said, with that small sardonic smile of his. “I think I’ll take a walk.”

“Aye, with care. Halfdan will follow you, Cormac mac Art-he has less steel to see to.”

Halfdan-called-halfman said nothing. He was built low to the ground, too, but like an ox. Thus the name jestingly given him meant naught to the short man, who could lift and hurl the likes of Cormac and who had sent many taller men to their fathers, and them longer of arm.

Cormac mac Art set off walking, along the shore to the eastward. He angled his steps inland to the rocky wall that stood between him and-whatever dark secrets this grim land housed, back of its lifeless shore.

Halfdan-and Knud the Swift as well-were just on their feet and clad in well-inspected armour when their Gaelic comrade called.

“Ho! A divide splits the rock here, and winds inland.”

Then he walked on past it, rounding a granitic spur that ran down to the very water. Around it Cormac peered, and shook his head, for there was only more rock, and the sea, which ran out and out to turn dark and melt against the farther sky.

They straggled up the sand, huge Wulfhere still buckling on a swordbelt like an ox-harness. Knud limped a bit on a turned ankle, and Hakon Snorri’s son had wiped face and left arm clear of patches of skin on the sand in his violent sliding along it. Hrothgar swung his right arm, wincing, whilst he constantly worked the fingers of his left.

Twelve men had died, and nine had been blessed of their gods. All could walk, nor was there break or sprain among them. Cormac’s lower back nagged; he gave it no more heed than had it been a hangnail.

In horned helmets and steely-rustling mail over leg-hugging trews that bulged over the winding of their footgear, the little band entered the narrow declivity Cormac had found. Natural walls loomed high on either side, no further apart here than the length of two men, as though in some time long gone a giant had carved out this entry to the interior with two swift wedging strokes of an ax the size of the father of all oak trees.

They walked.

And they walked the more, while barren cliffs brooded over them and chilled them in grim shadow. The declivity widened, then narrowed. It widened again, and still again drew snug, while it turned a half-score times like a road that followed a cow’s meandering path. Nor did the nine men see aught of man or animal, not even the wild fowls they had heard.

Then they rounded another turn in that winding corridor roofed with sky and walled with somber basalt, and they came to a halt, and every man stared.

“Odin’s eye!”

“By Odin and the beard of Odin!”

“It-it be a jest of Loki, surely!”

“It’s to Valhalla we’ve come for all that, and still no cup-bearer in sight!”

Thus did those stout weapon-men make exclamation, while they stared.

Before them the slash in the rock widened into a canyon. The canyon became a valley, dotted with fallen rock ranging in size from pebbles to great deep-set chunks large as houses. The expanse of the valley itself was such that they could discern no details in the great dark wall of glowering basalt at its far end. But it was not that natural wall that gave them pause and filled them with awe.

Here were man-made walls.

Between the lofty natural fortress and the stranded sea-rovers, incredibly, stood no less than a castle, a towered and columned palace of spectacular porportion.

– D’Arcy McGee,

“Not in all my years of wandering have I seen the like of this,” Wulfhere said, and not without awe. “Cormac?”

The Gael shook his head. “I have seen the palace of Connacht’s king, and served a king in Leinster and another in Dalriada, and it’s the halls of their keeps these feet have trod. But that man-raised mountain would hold all Leinster’s palace… aye, and a tenth of the kingdom of King Gol of Dalriada in Alba as well!”

There was nervousness in the voice of Knud. “Who… raised this mighty keep-and why here?”

“No man alive,” Cormac mac Art said, very quietly.

Slitted of eye, the Gael was studying the lofty and massive pile of carved stone blocks with its weathered carvings and bronze trim. Broad was its entry and finely arched, the product of science and skill. Arched windows were impudently wide, in scorn of possible attackers.

“Nor was this set here,” Cormac mac Art said into their awed silence, “by those Romans who thought they were the chosen of the earth. Those carved decorations… it’s from the Celts we Gaels sprang, and from the men of long-vanished Cimmeria the Celts sprang, and from the rulers of the world time out of mind that the Cimmerians came-the world-spanning Atlanteans. Aye. Atlantis…”

The Danes looked at him curiously.

He was staring, as though seeing the throngs of golden men in their other-land garb, the stalwart folk of that long-ago land now gone forever.

This was not the first time the scarred, sinister-faced Gael had seemed to slip away from them in this wise, as though he saw what they saw not, as though he spoke of a dream composed of pictures painted on the walls of his mind, and none other’s. His glacial eyes were invisible within their deep, slitted sockets as he stared at the visions of high civilization and artifice before them, and spoke on, quietly, in a droning voice.

“Kull,” he murmured. “Kull… An this great keep was not devised by the men of Atlantis and their slaves that were taken from the men and women of all the world, I am… not the son of Art na Morna, of Connacht, and him not the son of Conla Dair, son of Conal Crimthanni of the Briton wife of that Niall who was High-king over all Eirrin and gnawed at the heels of the Romans even so far as the land of the Gauls…”

“Cormac.”

“…and him the descendant of those worldspanning giants of old who sailed their high-prowed craft over all the seas of the world and came even here to…”

“Cormac,” Wulfhere repeated.

The murmuring Gael twitched, then jerked as though aroused from sleep. His hand dropped automatically to sword-pommel. He looked at the big Dane, and Cormac blinked.

“Why stand we here, when someone time out of mind has put this nice little house here for the cooling of our heels?”

The nervous men about him over-reacted by laughing uproariously.

They started forward, with Cormac suggesting, in a mutter that hardly disturbed the compression of his lips, that they stay not bunched. In that he was right, for when they were within fifty paces of the towering pair of columns flanking the door of that ancient keep, the arrows came.

Bow-loosed shafts came singing like angry wasps, but it was from the roundshields and surrounding stone they rattled, all save one. Wulfhere stared down at the slender stave that stood from his chest.

Then he laughed, and yanked it free of his mail, nor did blood come with it.

“Odin’s good eye,” he grunted, “the man who sped this feathered toy has the strength of a child of the Briton weaklings!”

More arrows whirred, but the little band was well scattered and ready now. They took what cover the terrain afforded, for after the long-dead men had erected the castle, boulders and stones and flattish shards of rock had come slithering and bounding down the cliffs to dot the plain.

Guthrum and Ivarr Ivarr’s son had their bows, and what few arrows they had saved from the greedy sea. They unlimbered bows, nocked feathered shafts, and glanced at Wulfhere. Each man squatted behind a tumbled boulder partially embedded in the earth, and held his bow sidewise. With a confident grin, Wulfhere muttered that he would rise to draw arrows-and reveal thus the positions of their speeders. Ivarr had picked up an enemy arrow; Wulfhere tossed his to Guthrum.

“Wulfhere.”

The voice was Cormac’s. Wulfhere turned questioning eyes on the Gael, who squatted behind a pile of shaly rock that had once been clay.

“Knud,” Cormac said, and when that man and, the giant leader were looking at him: “When the arrows come, Guthrum and Ivarr will both give them back a few. And Knud-you and I are the fleetest of foot. Shall we pretend demons are on our heels and run straight to the door of that keep, you to the leftward pillar?”

Knud grinned. “Aye,” he said, and inspected his buskins’ straps.

All were ready, and after a moment Wulfhere rose confidently to his feet, his legs protected by the massy boulder behind which he’d ducked. He waved his great ax so that the sun caught its silvery head and splashed dazzle-fire from it.

“HO-O-OH!” the Skull-splitter bellowed, and back rolled his voice from the canyon’s walls. “We’ve seen how your CHILDREN loose arrows-be there MEN among ye too?”

Aye, and an arrow sounded

All saw now that there was more than one floor within that lofty castle of old, and that it was from two high windows the keening shafts came. Ivarr and Guthrum joined Wulfhere in standing, and strings thunked as they sent arrows into those same windows.

Like runners in one of the races at the Great Fair of Eirrin, Cormac mac Art and Knud the Swift went racing castle-ward. Knud ran straight, trusting to his well-known speed afoot; Cormac wove a bit, for he was none so fleet of foot as the leggy Dane to his left.

Brave or foolhardy, one of the defenders exposed himself to speed an arrow at the Dane and, in a swift movement of hand to waist and back to bow, another at the runner. Cormac felt the arrow strike his belt or the armour there. He grunted and continued running. The castle rushed closer to him, while Wulfhere continued his madman’s bellowing-and from ahead and above came a scream of horror and pain.

Cormac grinned wolfishly. An arrow from Guthrum or Ivarr had paid the defender for his temerity, then, and in steely coin!

Cormac mac Art reached the castle. Despite his efforts to slow his headlong pace, he slammed a shoulder into the pillar. It was strangely white despite its age, and iron hard. No more than a grunt escaped the Gael, who met Knud’s eyes across a distance of several feet. Knud was there first, naturally enough, and himself not winded. Now the two found that the doorway’s width was full the length of a man. Too, it was open. The door itself, massive and ironbound, hung by one huge hinge-strap. It had been chopped well by several axes.

The defenders within did not belong here, Cormac reasoned, but had found this prodigious keep the same as he and his companions, and had hacked and smashed their way inside.

“They’ve left the door open in welcome,” Knud said, showing the other man his drawn steel.

“Shields low and sword ready and in, you to the left.”

They entered thus, in crouching movements that emanated from their toes, both men poised to wheel, run, duck, or drop.

A blank wall of well-cut stone met them. To either side a stone stairway ran up to a landing, turned, and vanished behind a wall. A nice way to greet invaders, Cormac thought;

The two men exchanged a look. With a nod they went each to a separate stairwell. Cormac went up cautiously, close-pressed to the inner wall, step after step with sword out and ready. Knud, who was left-handed as well as fleet as a deer, ascended the other stairway in the same manner.

At the landing, Cormac gathered himself and took a deep breath. He bounded all the way across the platform, into the far corner. By the time he alighted there, his eyes were turned upward and his shield covered his crouching body from collarbones to crotch. He’d had experience with bow-men, and good ones, and knew they seldom drove shaft at the more difficult target of head or throat, but at the midsection or below; a man with an arrow through his leg was more likely than not completely out of any fight.

But he was staring up an empty stairwell, and Knud had not been so clever.

Cormac heard him scream, but could not see the other landing. He soon saw the Dane nevertheless, for he came bumping and rolling back down the stairs. An arrow stood from his guts. He struck the floor face down, and a tent appeared in the back of his mailcoat as the weight of his own limp body against the floor drove the arrow all the way through him.

Without a sound, Cormac mac Art bounded up the second set of narrow stone steps. Passing a corridor to his right, he charged straight ahead. On the floor, in a shaft of sunlight from the broad window, a man lay still, with an arrow through his throat. Ivarr or Guthrum had shot well, at a man who had shown them only head and shoulders!

Another archer, crouched by that same window, was already whipping around and loosing a feathered shaft at the charging invader.

Cormac spun his left arm, trusting to the shield to find the rushing arrow. He was rewarded by the sound of ironshod wood ringing off ironbound buckler. Then his right arm came whipping around in a grey blur. He had a vision of enormous blue eyes beneath a small cap. of a helmet, and then eyes and the face in which they were set leaped high and were gone, as his blade sent the head flying from its shoulders-and out the window.

There was no time for so much as a grim smile at the, sound of an exultant cry from his comrades outside.

“COMMMMMMME!” the son of Art of Eirrin shouted, and then he was slamming his shoulder against a wall. From it dangled dusty tatters of an eons-old tapestry that had once lent beauty to these somber basaltic halls. From the corner of his eye Cormac had seen the appearance of another man, at the top of the steps at the far end of the broad corridor.

He wore a winged helmet, and he held a bow with arrow nocked. The string snapped home and the arrow came too fast for Cormac to see it, at this close range. His shield was angle-held, and the arrow was deflected with a ring and a rap of its tail that was followed instantly by the sound of its glancing off the wall to his left.

Already another arrow was being fitted to string.

Only an idiot charged an archer at such proximity. Had he been a bit closer, only an idiot of a bow-man would have tried to stop attack with an arrow. As it was, the other man had the better of it, and Cormac adopted an uncoventional defense and attack-born of desperation.

With all his might he hurled his sword at the archer.

At the same time, he lunged wildly leftward, toward that gaping window. Even then he was mindful of keeping his buckler betwixt him and the enemy.

It was unnecessary; the disconcerted yeoman sent his shaft on a wild upward angle, in his attempt to dodge the flung sword. He did not succeed, nor did it do him harm. But in the seconds he took to recover from that ridiculous “attack,” his foe covered yards of stone floor.

Cormac’s shield smashed into the other man’s breast and face and the Gael’s dagger drove into his belly, its impact heightened by the speed of his charge and muscles so powerful that mail parted like paper. The dagger’s hilt clanked against steel scales.

With a deliberate twist of his wrist, Cormac jerked the blade back and swung the shield straight up, away from the clawing hand that sought to grasp it.

Nose smashed and belly gutted, the wide-eyed man in the winged helmet staggered back one step, then two. The third time his foot came down not on floor, but on empty air, and then the topmost step.

The man Cormac recognized as of the Norse went tumbling and clattering and clanging down the stone stairwell.

“What’s this?” a great voice came bellowing up. “Cormac sends us a gift of welcome?” And there was a

Knotty-legged Wulfhere rounded the corner of the landing, and then Hakon and Ivarr, and from behind himself Cormac heard others of his Danish companions, who had come by the steps he had chosen. For the space of several seconds, all stood in that ancient corridor and stared at each other, in wondering silence.

A great castle the size of a Roman circus and the height of an oak lofty enough for the highest Druidic rites-and but three men to defend?

Aye, for by the time the sun had moved across the sky the length of two joints of Cormac’s finger, the eight men had assured themselves that the castle was empty of life other than their own. But not of other things…

“It be the hiding-hie and treasure-keep of a band of rievers,” Cormac muttered, as they stood to stare with greed-bright eyes at what they’d found. “And them off a-roving. They came upon this place as we did, and made it theirs, and left three of their number as guards. Against nothing, for we should not be here but for that treacherous wind.”

“And they’ve gone a-raiding again,” Wulfhere murmured.

They gazed at the large room piled and strewn with bales of fine fabric and, cloaks, and arms, and gold and gems that gave off their dull light in the dimness, and they nodded.

“Touch,” Wulfhere said, and stepped past the Gael. His word was a warning and assurance that he meant not to grab for himself.

The bearded Dane scooped up and held aloft a string of shining pearls the colour of milk and the size of large peas. There were full thirty on the strand. He brandished them, shaking his head.

“From far and far came

“Find me the women!” Ivarr called.

“Find me the ship,” Cormac said darkly, and the laughter died.

So too had Knud died, and the three men from Norge, nor could they be sent their way properly into the world of grim shades or high joy. Their laden bodies were removed to the sunlight, each wrapped in rich cloth from the booty. With more of that dear fabric that was surely for the cloaks and robes of kings and their women, the Danes and their Gaelic comrade wiped and mopped up the blood. Wulfhere was unyielding: no disporting of themselves until the dead were away. And so all of them carried those four in their purple and scarlet wrappings back along the valley, and along the narrow defile that opened into it, and far down the beach. And on their return, despite their anxiousness, they obliterated their own tracks.

Then did the eight return to that magickal castle from a time long gone, for they had found other booty there as well: food, and ale. There was even a small quantity of wine. And the fabulous room that might have contained an army of hundreds.

In it, their voices echoing, they ate, and drank. There was many a growled admonition from Wulfhere and Cormac against gluttony in the matter of wine and ale, for those who had first found this unlikely place might return at any time. Nor would their number be so few as eight.

Eeriness struck among them. Seconds after he drank of the ale, Snorri Evil-eye groaned, and his wayward eyes bulged, and he gasped and rattled deep in his throat. Then he fell. He was dead.

Men who had faced death and slain, and that bloodily and often, stared at him and at each other, and their flesh crawled.

“Sorcery,” Halfdan whispered, for his mind was of such a bent more than his companions’.

“It’s the sorcery and the power of the Druids I’ve believed in all these years,” Cormac mac Art said quietly, “but never have I seen its evidence.”

Others looked at him, hopefully. Then Wulfhere spoke.

“Call it then the displeasure of the gods, and the delayed death I have seen afore with these eyes. It was within himself that poor old Evil-eye took some injury, when the sea flung him upon the strand. But he knew it not, and felt nothing of it-until now, when he sought to drink. Any man knows that inward injuries may leave no sign upon the body-and later bring such results.” He gazed down at their dead companion.

“Aye,” a voice said in relief, and a ruddy-haired hand went out for a pothern of ale.

“Mayhap,” Cormac said. “But it’s none of that strong drink I’ll be tasting.”

Widened eyes fixed upon him, and his words did more to protect their sobriety than all Wulfhere’s grousing, though Cormac was as sure as the huge Dane that it was unknown internal injuries had slain Snorri thus.

Striding to the grand old throne of ironwood that sat imperiously on its dais, Guthrum whipped from its base the bale of purple, shot through with cloth-of-silver. Ivarr had placed it there’ as a joke: an offering to the invisible king of this land. With the cloth, Guthrum now covered their dead companion, and wound him about.

They had been one and twenty, and then nine, and then eight, and now they numbered but seven.

Slowly they returned to the business of filling their bellies, but with less noise and jubilation. Cormac would have liked to be in the magnificent dome overhead, and it set with a cyclopean eye that must have been the size of his shield. For he knew how ridiculous they must look, so few in this vast hall.

Into it could have been fitted the house and entire grounds of Gol, King of Dalriada on the coast of Alba, in whose service Cormac had borne sword until the king did treachery on his fellow Gael, for kings must see to their daughters.

Supported by a double row of lofty columns thrice the thickness of Cormac’s body or twice Wulfhere’s the room was; the length of two men separated the pillars of that colonnade, and in each row there were five and twenty. Round about them the walls were etched and carved with decorative swirlings and scrollwork and stylized representations of the sea, and ships on its breast.

In addition the walls told a story in pictures scratched into their surface with fine tools, and Cormac walked to read it.

Men had come here in great ships that could have carried within them three or four such as

The wall pictures showed those mighty serpents, prodigiously large and surely exaggerated-but Cormac mac Art knew without knowing how he knew that this wall was history, and without embellishment. The sons of men met in battle those who had preceded them and were loath to give up the world they had so long ruled. There was a great war, and the golden skinned men of Atlantis prevailed.

Cormac blinked. He jerked his head from side to side, looked up and around.

Again he shook his head, sharply and more than once. And he was again Cormac, son of Art of Connacht in Eirrin, and nothing crowded his head but the present, and his own memories of this short lifetime-memories that were entirely enough, and bad enough.

He studied the wall, biting his lower lip to make sure he was not distracted into some dreamish world he could not explain and thus resisted with all his sanity.

Unless he missed his guess, those islands the engravings showed the ancients exploring were Britain, and beside it Eirrin, narrow to the north, and above it Alba that the Romans called Caledonia. Strange beasts had roamed their soils then, Cormac saw, and serpents too. He smiled a little, for surely this triumphant etching showed why it was that green Eirrin was free of serpents but contained only toads and a few trifling lizards: the ancient sea-roamers and palace-builders had slain the serpents on that soil, every one.

A new feeling came over him, and he liked it no better than the remembering that was surely false. As though sorcerously drawn out, his finger went forth to touch a certain portion of the isle he thought must be Eirrin. Connacht, western home of the Shannon’s source. Green Connacht with its long ragged hills that were blue in the distance, its fens and plains and slopes and its bogs. Connacht of Eirrin; here it was that the son of Art had been born, and raised, until…

Cormac turned away from the wall and the story it told.

No longer was he interested in that tale of ancient triumph, or either in food, or the companionship of his Dane-born fellows. If the wall there past the throne showed what had happened to take away these great seafarers and builders, long long centuries agone, he was not interested. No matter what they had recorded, and builded here, it was exiles they’d been. So too was Cormac mac Art exile, and it came down on him now, in the great hall of what must have been his ancestors of a thousand or ten thousand years ago. What matter how long?

Before his eyes he saw the face of his father. And then again, but changed, for these were the blue eyes Cormac had last seen, and them fixed in death. The son of Eirrin gritted his teeth, for it was no natural death his father had got, and his dangerously-named son just at the age of manhood at the time, fourteen winters and thirteen summers old…

Cormac swallowed. He flicked his gaze to his fellows. Wulfhere was staring at him.

“Has it come upon you again, old friend?”

Cormac stared at him.

“The remembering?”

Cormac’s face was expressionless. “We be vulnerable as sea-dogs in their mating season,” he said gruffly. “I’m for scaling one of the cliffs outside-the westward looked to have handholds enow-and keeping a seaward watch. It’s a bow and two arrows I’ll be taking, for a warning if need be.”

“Cormac-”

But the Gael, his eyes bleak and his shoulders seeming somehow less broad and confidently set, was leaving them. He said no more, nor did he look back…

“There be an enchantment on that man,” Wulfhere said, and he heaved a sigh. “Some say we have trod this world before, all of us. Cormac knows it.”

“Aye.” Ivarr nodded. “Know you what he dreams of, when he goes away thus, and him still with us?”

“A yesterday he cannot possibly know.”

“And-”

“Eirrin.”

“We shall lose his sword and companionship some day,” Hakon said, staring fixedly as he ruminated, for it came not easily upon him, the thinking.

“Aye, and his counsel, that crafty calculating warrior’s brain of his!”

“And it’s not to sword, or arrow or spear we’ll lose Cormac mac Art.”

Again Wulfhere nodded, and again he uttered the single word: “Eirrin.”

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |