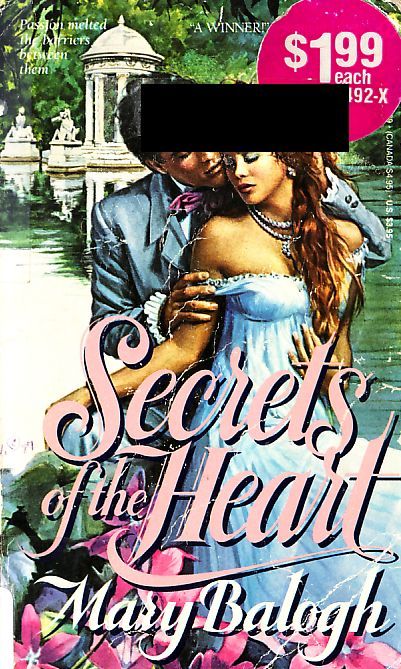

"Secrets of the Heart" - читать интересную книгу автора (Balogh Mary)

|

Mary Balogh

Secrets of the Heart

Chapter 1

The CITY of Bath during late summer was crowded with visitors from the fashionable world. At nine o'clock in the morning it was already alive with activity. The focal point of it all was the Pump Room, close to the imposing Abbey and next to the baths, the only hot springs in all England. The Pump Room itself was a long, high, elegant room with tall, arched windows stretching down its length, those on one side looking down on the King's Bath, in which many bathers sat immersed to the neck for the sake of their health. Also on that side of the room were vendors selling glasses of the sulfur water, also for the health of the drinkers.

Yet crowded as the room was, it was not full of invalids. This was the fashionable place to be before breakfast, a place where one might promenade and show off one's attire and admire or criticize that of others, where one might see or be seen, gossip or be gossiped about. An orchestra played from an upper gallery, but it is unlikely that many of the strollers paid it much attention.

Two ladies were not walking with the rest. Lady Adelaide Murdoch, an elderly widow, was seated at one end of the room, a glass of water in one hand, a lace handkerchief clutched in the other. The expression of distaste on her face suggested that she was finding her morning drink somewhat disagreeable.

"Bah!" she said to the young lady who stood at her shoulder. "If the Reverend Peabody had not told me himself that the waters would work miracles for my rheumaticks and my digestion, I should say that this was all a clever hoax. Water sellers, bath attendants, subscription collectors: everyone"-the hand that held the linen swept in an arc to encompass the whole of Bath around them-"making their fortunes at the expense of poor unfortunates like me."

"Perhaps when you have finished drinking, ma'am," her companion suggested calmly, "you would like to lean on me and take a turn about the room. I see Colonel Smythe and his lady farther along, and Mrs. Marchmont and her daughter said they would be here this morning. I expect they will arrive soon. You know you enjoy some lively conversation. It will take your mind off the ghastly taste of the water. Really, ma'am, I think you are downright heroic to take two glasses each day."

"Much good it does me, too," Lady Murdoch grumbled, "except to make my pockets lighter and to fill the purses of these thieves." She glared accusingly into her glass, wrinkled her nose in disgust, and sipped grimly at the contents again.

Miss Sarah Fifield gazed around her with some interest. The room was become familiar to her after a week of daily visits, and the people in it were also taking on names and characters. With several she was acquainted. It was easy to make acquaintances in Bath, she found. It was a policy of the masters of ceremony to promote an intermingling of the visitors. Private parties were discouraged, as was a cliquish clinging together of people of high

Sarah was beginning to feel relaxed; she was almost enjoying herself. And that was certainly an unexpected development. She had not wanted to come to Bath, had shrunk from the prospect in some horror, in fact. She could not remember feeling enjoyment in four years. But she was beginning to feel that after all, her secret would not be found out, that perhaps she could accept the pleasure of these few weeks before retiring to obscurity again. Obscurity was really the only safe way of life for her, the only possible one.

She had lived in obscurity for four years, alone, with the exception of Dorothy, her servant since before she had been orphaned. And she had learned contentment, if not happiness there in that little cottage. There she had recovered some of her self-respect, some of her confidence. And she would have been contented to stay there, occupying herself with her needlework, her books, and her garden, consoling herself with her close friendship with the Reverend Clarence and his wife. And she would be living there still if it were not for that fiend Winston Bowen. Thanks to him she had suddenly found herself without money, and she had been forced to seek employment.

She had sent an advertisement to the London papers in an effort to obtain a situation as a governess. She had had a totally unexpected reply from Lady Murdoch, childless widow of a baronet, claiming that she believed herself to be a relative and asking if Sarah was the daughter of David Fifield. A few days after Sarah had written to confirm this fact, Lady Murdoch had arrived on her doorstep, leaning her considerable weight on the shoulder of a liveried footman. She was delighted, she had said, to discover the daughter of her favorite cousin's son.

It had seemed a very distant relationship to Sarah, but Lady Murdoch had insisted on making much of it. She had no one of her own. Not that she was lonely, she had hastened to explain. But sometimes it was provoking to hear her acquaintances boast of their children and grandchildren when she had no one. She realized that Sarah must be in desperate straits if she was prepared to hire herself out as a governess. She wanted Sarah to come and live with her.

"I need a companion, you see, dear cousin," she had said in her strident voice, "and it will be all the better if she is a young relative. Will you come?"

Sarah had hesitated. "Perhaps you would care to employ me, ma'am?" she had suggested at last. "I really could not be so beholden to you as to do nothing in return for your kindness."

"Employ a relative!" Lady Murdoch had exclaimed, appalled. "Nonsense, cousin. I would prefer to consider you the daughter I never had. Granddaughter would probably be the more appropriate relationship, for I am sure I am old enough to be your grandmama. But forgive an old woman's vanity. It seems such a short time since I was of an age with you. How old are you, cousin?"

"Three-and-twenty, ma'am," Sarah had replied.

"Three-and-twenty!" Lady Murdoch had repeated. "What is your aunt Bowen thinking of to allow you to live alone at that tender age? I understand that you were under your uncle's guardianship after your dear papa passed away?"

Sarah had nodded and held her breath. Had Lady Murdoch also heard of the great scandal? But she had concluded almost immediately that she could not have. She surely would not have come if she had.

The outcome of the visit was that Sarah had packed up her belongings and moved away to Devonshire with Lady Murdoch. She was amazed to think that this distant cousin was prepared to take her in with so little knowledge of what she was like. She judged that Lady Murdoch was far more lonely a person than she would admit.

And Sarah had found herself treated like a daughter from the start. She took her position as companion seriously and would have far preferred to be paid for doing that job, to have been merely an employee. As it was, she had had a new wardrobe and numerous trinkets showered on her, as well as pin money, which she found impossible to refuse.

When Lady Murdoch had announced that they were to go to Bath Spa in late summer, when a large portion of the fashionable world would be present, she was horrified and thought of all sorts of excuses to be left behind. She could not go into society. Her secret would be found out in a day. It was true that she had changed her name, or at least resumed her real name rather than her uncle's name of Bowen, which she had taken on to please him when she moved into his house on the death of her father. But she had done nothing else to cover her tracks. It needed only one person to discover the truth and all of Bath would know in no time at all.

She had agonized over whether to tell Lady Murdoch the whole truth or not. She should have done so at the start. But finally she had decided to take the risk. She had heard that Bath was not quite as fashionable as it had used to be. Most of the late-summer visitors were reputed to be older people. Going to Bath, then, would not be quite like going to London. She would not have dared go there.

But for the first few days she had been terrified. She had expected everyone she passed to turn and point an accusing finger at her, and she had cringed from introductions to acquaintances of Lady Murdoch or to new acquaintances presented by the master of ceremonies of one of the assembly rooms. And miraculously no one seemed to realize that she was different from everyone else. No one had come to order her to leave Bath and all respectable society.

She-had been timid, almost ashamed at first, about meeting new people, knowing that she had no right to be in their company. But soon enough she had discovered some exhilaration in being accepted as any normal human being and in being admired. She knew she was beautiful; she knew that her generous figure and masses of red hair were unusually attractive. She had never been proud of these attributes. In fact, they had been directly responsible for her downfall. But suddenly she found it a heady experience to be sought out by the few young and attractive people who were in the city, and to be smiled at indulgently by the older friends her cousin was making.

It was all wrong, of course; she knew that. But she was not intending to make any permanent connections. After a few weeks she would leave behind all these people and never see them again. Surely it could not be wrong to enjoy those few weeks. There had been so little of joy in her life. Her youth had been cut very short. She had been barely nineteen…

Thus Sarah looked around the Pump Room with interest.

"Yoo-hoo!" Lady Murdoch called suddenly, making Sarah start with surprise. She winced as she watched her cousin wave her handkerchief in the direction of a gentleman who had just entered the Pump Room.

Several eyes turned in the direction of the two ladies, including those of the gentleman who had been hailed. He smiled, crossed the room, and bowed elegantly before them. He took Lady Murdoch's hand, handkerchief and all, into his own kid-gloved one, and raised it to his lips.

"My dear Lady Murdoch," he said, "you are becoming hardly recognizable. The waters are reputed only to heal infirmities, not to rejuvenate. But I swear you look years younger than when I saw you two days ago."

Lady Murdoch threw back her head and barked with laughter. She appeared quite oblivious of the eyes and quizzing glasses that again turned in her direction.

"Famous!" she said. "You should have been on the stage, Mr. Phelps. I have been telling you so these twenty years, since my dear departed husband first bought those horses from you in London. Both lame! And if I really had lost all the years you always claim, I should be an infant in my mother's arms again."

Mr. Phelps smiled and twirled in his hands the top hat that he had removed from his head. He looked at Sarah. "Ah, the divine Miss Fifield," he said, bowing again. "Still breaking hearts by the score, I do not doubt. Or am I the only one whose invitations to walk and drive you consistently refuse, cruel one?"

Sarah made him a half-curtsy. "Milsom Street is strewn with them, sir," she said. "With broken hearts, I mean. I am afraid there is little I can do about it. My time and attention are all devoted to the care of Lady Murdoch."

The lady in question crowed with laughter again. "A hit!" she said. "Come, you must admit it, sir. Now, do tell me, is it true that Lord Barton lost three thousand at cards last night? That is what Mrs. Watkins told us as we came in, is it not, cousin? But one never knows with that woman. Three days ago she told us that the Regent himself was planning to come here for a week, and it turned out that there was not a word of truth in the rumor."

"Well, of course, ma'am," Mr. Phelps began, bending his head close to that of his questioner, "I do not gamble myself, you know, but it is said…"

Sarah's attention wandered. She found Mr. Phelps amusing. He was a fashionable dandy in his forties, a man who delighted in gossip and in light flirtation. His attentions to her would stop very fast, she guessed, if she once began to take them seriously. She had found that answering his flattery in a flippant manner kept him hovering in her vicinity, pretending to languish after her.

She smiled at the approach of Colonel and Mrs. Smythe, a couple also in early middle age, with whom she and Lady Murdoch had sat at a concert in Sydney Gardens a few days before. With them were the Misses Seymour, two sisters who lived permanently in Bath with their mother, widow of a clergyman. They all stopped and talked with her for a few minutes, but she declined joining them in a stroll about the room, choosing rather to stay with Lady Murdoch. She similarly refused Mr. Gregory Evans, a young and earnest landowner who had been presented to her the day after her arrival and who had singled her out each day since.

Lady Murdoch and Mr. Phelps were still deep in conversation. Sarah looked around her again. It was becoming almost a rarity to see new faces in the Pump Room. The group of people who had just entered looked unfamiliar, though she could not see their faces to be sure. They stood with their backs to the room, looking at the baths below. One of them was an elderly lady, though very different from Lady Murdoch and many of the others of her generation in the room. She was slim and held herself ramrod straight and moved without assistance of cane or human arm. She was fashionably dressed in lavender walking dress and dove-gray bonnet. She was in company with a gentleman and two young ladies, one of whom had an arm resting in the crook of his, though she stood as far from him as her arm would allow. Both girls looked very young, judging from the back view Sarah had of.them. The man was of medium height, slender, graceful, and elegant in green coat, biscuit-colored pantaloons, and black Hessians. Obviously they were people of fashion.

"Bertha!" Lady Murdoch released the name into the middle of a confidence that Mr. Phelps was sharing with her. "Bertha Lane. Yoo-hoo! Bertha!"

Sarah cringed and wished for one moment that she were anywhere but where she was. The handkerchief was again waving in the air, and Lady Murdoch was looking directly at the new arrivals who had been attracting her own attention.

The next moment Sarah was beyond even wishing she were elsewhere. She was paralyzed, mesmerized, lifted totally beyond time and place. The whole group had turned, as indeed had many other promenaders. But Sarah saw none of them except the man. No one except George Montagu, Duke of Cranwell. The man whom, of all others, she had dreaded to see again this side of the grave.

The Duke of Cranwell had agreed with some reluctance to travel to Bath. His idea of pleasure did not include the assemblies in the Upper and Lower Rooms, gatherings in the Pump Room, concerts in the park, and shopping and gossip expeditions in the crowded streets. In the summertime, particularly, the prospect was far from appealing.

His idea of comfortable living was to reside at Montagu Hall, his Wiltshire home. The large park offered everything in the way of quiet exercise: lawns and hills and woods stretching in every direction far out of sight of the house. His farms gave ample challenge to his mind and his physical energies. And the house was his pride and joy, the possession that gave his life its chief purpose. In the ten years since he had inherited the title and the estate from his father, he had filled it with art treasures and elegant furnishings. He had remodeled parts of it for more comfortable living. He, would have been well content to rusticate there for the rest of his life.

Unfortunately, he reflected, when one had decided to give up one's single status for the advantages of matrimony, one had also to give up one's freedom to do just what one wished with one's life. He was nine and-twenty and it was high time that he gave up his strong aversion to marriage, well-founded though that aversion might have been. He had no brothers, and his closest male relative was a stranger to him and did not even bear the family name. The title had been in the Montagu family for five generations, and he hated the thought that it might pass to a family of another name if he failed to do something about the matter.

He had not taken great pains to find himself a prospective bride. He could have gone to London for the Season and looked over the crop of young girls newly "out." There he might have looked at his leisure for a lady of beauty and breeding and wit and intelligence and any other qualities that he supposed might be desirable if he gave the matter sufficient thought. But he had decided against such a step. He knew what would happen if he went. Almost every marriageable girl in town would set her cap at him, and it would be very difficult to know the true character of someone chosen under such circumstances.

Cranwell had winced at the thought. It had happened to him once. He had been deceived by a woman, and he had no wish to repeat that experience. He had been four years younger at that time, young and naive enough to believe that when a lady showed interest in him Ind avowed love for him, it was really him her attention was focused on. It had taken a bitter and painful experience to learn that his dukedom and his wealth and property could be far more attractive inducements than either his person or his character.

When he chose, therefore, he looked for nothing in a bride beyond youth and the apparent ability to breed. And purity, of course. That last was very important and the most difficult of all to be sure of in a stranger. Thus he did not choose a stranger. He chose Lady Hannah Lane, daughter of the Earl of Cavendish. The family lived in neighboring Gloucestershire, and a fast friendship had existed between the earl and the late duke. Cranwell had known Hannah from her infancy and could be reasonably sure of several things about her.

She was seventeen years old and not yet "out." All her life had been spent in the country, either at her father's home or at that of her grandmother. She had been out of the schoolroom for only a few months. She had had a strict and sheltered upbringing. These facts had merely emphasized a natural shyness and timidity of character. Cranwell had discovered during a visit to her father's home that she seemed well-bred and sensible, though she did not have a great deal of conversation. She had some beauty, being small and fragile in build, with honey-colored hair and skin that was almost translucent.

He had offered for her and had been accepted before his return home. The whole transaction had been made between him and Lord Cavendish. He had had only one short interview with Hannah, during which he had made a formal proposal and been accepted by a tongue-tied girl who had not once looked at him.

Cranwell would have been quite content to spend the summer quietly at Montagu Hall until it was time to claim his bride at Christmastime. Not that life at home was as peaceful as it had used to be. His young sister had returned home from school a couple of months before. Fanny had always been a girl of ebullient spirits, but now she seemed positively to)ounce with energy. Her schooling was over and she was bursting to taste all that life had to offer. Already she was pestering him for a come-out Season in London the following spring. It gave him quite a jolt to realize suddenly that she and Hannah were of an age. Fanny seemed the merest child. He realized guiltily that he was almost robbing the cradle to have engaged himself to Hannah.

If the presence of Fanny was not enough to rob him of his peace, Cranwell had discovered that the dowager Countess of Cavendish certainly was. She was delighted with the news that her granddaughter was betrothed to the duke, of whom she had always been fond. But she was loudly disturbed by the fact that Hannah had had no come-out. Her son would not hear of postponing the nuptials until the following summer so that his daughter might be taken to London and duly presented at St. James's. There was only one solution, albeit an unsatisfactory one. Hannah must be taken to Bath, where she could at least mingle with society for a few weeks. And if Hannah and the dowager were to go to Bath, Cranwell discovered ruefully, he was to go there too as their escort. And if he was going, then Fanny could not be left behind, even had she wanted to be.

Hence the Duke of Cranwell, who liked nothing better than a quiet life in the country with his farms and his art and his books, found himself by late summer amidst all the bustle and glare of a health spa.

He left the White Hart Inn, where he was staying, at eight o'clock on the morning after their arrival and walked through the Pump Yard, already filling with fashionable men and women on their way to take the waters or seek out gossip. It was no strange matter for him to be up so early. Indeed, he had been sitting in his room reading for upwards of an hour before leaving. But he wondered with inner amusement how the ladies would take to such early rising. Fanny, he knew, rarely put in a public appearance at home until close to noon, and even then she was frequently as cross as a bear until she had breakfasted. Unfortunately, the days at Bath progressed quite strictly to timetable, and the hours of seven to ten in the morning were the fashionable time to take the waters and promenade in the Pump Room.

All three ladies were ready when he arrived in Laura Place, where they had taken lodgings. Lady Cavendish was sitting straight-backed in a chair, looking for all the world as if she had been sitting there for an hour or more already, and Hannah was sitting quietly at her side. Fanny was in a temper, Cranwell could see at a glance, standing at the window of the sitting room glaring out at the sun-bright street.

"I really don't see why we have to be up in the middle of the night, George," she said, rounding on him as he was shown into the room. "Surely no one will be out at this ungodly hour."

"On the contrary," he said. "The Pump Yard was full of people as I passed through it ten minutes ago. I would imagine there is quite a squeeze in the Pump Room already." He bowed to Lady Cavendish and Hannah. "Good morning, ma'am," he said to the former. "Are you still determined to walk this morning? It is not too late for me to go for a carriage. My dear?" He took Hannah's hand and raised it to his lips.

"Take a carriage?" Lady Cavendish said, rising to her feet. "And miss seeing who is who on the street? My dear boy, you will find that I am not yet quite decrepit with age."

"Well," Fanny said, taking her bonnet from the window seat and tying the bow beneath her chin, "what are we waiting for? If we do not leave at once, we may miss all the morning's entertainment."

When they left the narrow three-storied building on Laura Place, Cranwell took Lady Cavendish on one arm and his betrothed on the other. The latter, he noticed, walked as far distant from him as her arm would allow and proceeded along the pavement with lowered eyes. She had not said a word to him that morning beyond a polite greeting. He wondered suddenly if she were not somewhat in awe of him. The idea irritated him a little, but he supposed that if it were true the fault must lie with him. He must make the effort to find some topic about which they could converse. They must surely have some interest in common.

Fanny tripped along ahead of the others, her parasol twirling about her head. She gazed with animation — it the scene around her, apparently having forgotten that humanity was not intended to function at such an ungodly hour of the day. As they passed the Abbey, at which she stared with some awe, having lowered her parasol so that she could look up with more ease, Lady Cavendish joined her, declaring that it was impossible to walk through such a crush three abreast.

Cranwell was not cheered by the sight that met his eyes when they entered the Pump Room. Despite the earliness of the hour, the room was crowded. Some people were clustered around the water vendors; most were strolling or standing in small groups, talking. He sighed inwardly. It was unlikely that he knew many of the room's occupants. He had not ventured far from his home in the previous few years. But undoubtedly Lady Cavendish would know many people; she spent several weeks of each year in both London and Bath. And, of course, they would all be expected to make new acquaintances and to socialize almost constantly. It was an unwritten rule of Bath, he had heard, that one be part of the social life and participate in the many and varied activities that the city offered.

Fanny was exclaiming with enthusiasm as she gazed down at the King's Bath below the window. Lady Cavendish was explaining something to her. Cranwell too stopped and turned to his companion.

"Did you expect such a squeeze, my dear?" he asked. "I must confess that this all takes me somewhat by surprise."

"Grandmama has told me that we would meet many people here, your grace," she said. Her voice was toneless. She did not look up at him but directed her eyes through the window.

He opened his mouth to continue this unpromising line of conversation.

"Yoo-hoo! Bertha!" a voice called from behind them.

Cranwell had turned before he could stop himself. But then he noticed that many other people had done the same thing. It was not difficult to locate the source of the greeting. A very plump elderly lady sat on a chair not far away, waving a handkerchief in the air. Cranwell was about to turn away and draw his party farther down the room away from such a vulgar display when he realized with some dismay that the handkerchief was waving exactly in their direction. And Lady Cavendish was Bertha, was she not?

He drew Hannah's arm a little more firmly through his own and glanced quickly around to make sure that Fanny was close by. Then he looked back at the elderly person in the chair, who was now smiling and still waving the handkerchief. A gentleman approaching his middle years stood to one side of her and a young lady at her shoulder. Both looked perfectly respectable.

His eyes passed carefully over each of them. But if he had felt dismay at having his party so singled out for public attention, he was struck by a paralyzing horror when his eyes came fully to rest on the face of the young lady. It could not be! was his first reaction. His eyes and his mind were playing tricks on him. But it was. It surely was. There could be no mistaking that golden-red hair, half-hidden though it was beneath her bonnet. No mistaking those arched eyebrows, which always gave her face a look of surprise, and that full, curvaceous figure. It was Sarah, right enough. The one woman in this world whom he had hoped never to set eyes upon again.

"Well, Adelaide Murdoch, I declare," said Lady Cavendish. "I might have known it without even looking. No one else of my acquaintance could hail a person in such an improper manner and get away with it."

She swept across the floor in the direction of Lady Murdoch, her face beaming, her hands outstretched. "Adelaide, my dear friend," she said, "what a delight it is to see you again. It must be all of five years."

Lady Murdoch reached for Sarah's outstretched arm as a support on which to raise her considerable bulk to her feet. "Bertha," she said, "I knew as soon as I saw you standing over there that there could be no other female of your age who has kept her figure and her health so well. How do you do it?"

Lady Cavendish acknowledged the compliment with a nod. "What are you doing in Bath, Adelaide?" she asked. "Taking the waters? Allow me to present my granddaughter to you. Hannah, my love, meet one of the dearest friends of my youth, Lady Adelaide Murdoch."

Lady Murdoch clasped the hand of the girl who curtsied before her, having handed her empty glass to Mr. Phelps. "Yes," she said, "your grandmama and I have been friends since we were your age, my dear. Ah, and in those days we were both as slim as you, too."

"May I also present Lady Fanny Montagu and her brother, the Duke of Cranwell?" Lady Cavendish continued. "Hannah and his grace are to be wed before Christmas."

Fanny curtsied and Cranwell made his bow.

"The Duke of Cranwell!" Lady Murdoch exclaimed, clasping her hands over her ample bosom and gawking at him. "Well, I declare. Oh, pardon me, your grace. It is not every day one meets someone of such superior rank. I have heard about you, you know. My dear friends the Withersmiths were given a tour of your home last summer when they passed through Wiltshire, and talked of nothing else for weeks afterward. You were from home at the time. Your housekeeper did the honors, I understand."

Cranwell bowed again and murmured some platitude about being sorry that he had missed making the acquaintance of the Withersmiths.

"And my manners have certainly gone begging!" Lady Murdoch exclaimed, gripping more tightly the arm on which she leaned and turning sharp eyes on Sarah. "May I present my cousin and dear companion, Miss Sarah Fifield? And Mr. Marcus Phelps, who was a dear friend of poor Dicky's, Bertha."

Somehow Sarah lived through the introductions and the ten-minute conversation that ensued. But she did not know afterward how she had done it. He looked so familiar standing there, though she had not set eyes on him for four years. The same slight, graceful figure that somehow escaped being either puny or effeminate. The same dark, shining hair and thin, ascetic face with the straight nose and sensitive mouth and deep blue eyes. And that same elusive aura of attractiveness, which owed its existence to no nameable physical feature.

She looked directly at him when her name was mentioned and found that he was looking back with raised eyebrows. He inclined his head in a stiff half-bow and did not look at her again. She could not move. She hardly dared breathe. What would he do now? Lead his party away from her contaminating presence as soon as he decently could and stay as far from her as possible for the remainder of his visit in Bath? It seemed unlikely. Lady Cavendish and Lady Murdoch seemed mutually eager to renew their friendship. Would he expose her publicly as the fraud she was? Perhaps not publicly. George had much to lose himself by doing that. But privately, maybe, when he had his little group of ladies alone? Her acquaintance and doubtless that of Lady Murdoch would be cut quietly. Rumors would begin to circulate in Bath and the nightmare she had dreaded for four years would he reality.

Lady Cavendish was assuring her friend that, yes, indeed, his grace had paid their subscriptions the night before, immediately after their arrival, and yes, they would most certainly be at the Upper Assembly Rooms that night to take tea. Sarah looked at Lady Hannah. She was very young, very pretty. Very innocent. Yes, those qualities would appeal to him. She would be a very suitable bride for the Duke of Cranwell. Sarah lelt sick. Four years, after all, did not seem such a long time. Could he really be considering marriage already? Why had she not worked harder during those years to stop loving him? He looked so familiar, yet was so totally unapproachable.

The Duke of Cranwell had often wondered in the years since he saw Sarah last why he had fallen so headlong in love with her. He must have been merely ripe for an infatuation, he had persuaded himself. No female could be as beautiful, as fascinating, and as physically appealing as he had thought her. He had convinced himself that he had never really loved her and that therefore his loss had not been so great. But lie had to admit to himself now, having permitted himself one searching look into those green eyes, that tic had certainly not underestimated her beauty and physical appeal. She looked appallingly familiar to him, as if it had all happened but yesterday, although it he had tried to recall her face and figure the day before, he could not have done so with any exactness.

As shock receded, anger took its place. How had she dared to come to this place of fashion and decency? And under a different name! How could she stand there calmly supporting the weight of her elderly cousin, who must herself be a respectable person if Hannah's grandmother deigned to recognize a friendship with her? Did Lady Murdoch know? he wondered. Of course, Sarah would contrive some way of avoiding future contact with him and the ladies for whose welfare he was responsible. He must at all costs protect Hannah and Fanny from contamination. He felt the old hatred and was as little able to cope with the emotion as he had ever been.

Finally, to the infinite relief of both Sarah and Cranwell, Mr. Phelps made his bow and announced that he was expected back at his lodgings for breakfast, and his departure set everyone to remembering that they had not yet eaten and that it was high time they did. Lady Cavendish and her party set out to walk back to Laura Place, and Sarah helped Lady Murdoch outside, where the carriage they had ordered for half-past nine waited to return them to their lodgings on Brock Street.

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |