"Talk About Sex: An Orientation" - читать интересную книгу автора (Callan Jamie)

|

Jamie Callan

Talk About Sex: An Orientation

All I'm going to do is talk. That's right-you're going to pay me to sit here and talk to you. Let me explain-I come to your hotel room, I always wear something nice, maybe a jacket and matching skirt, or a simple dress, pearls, always stockings, always heels, always tasteful. I sit on your bed, cross my legs, smile, and then I talk about sex. You're not allowed to touch me. That would be breaking the rules. I talk for exactly forty-five minutes. I always finish on time. I charge three hundred and fifty dollars. I accept all major credit cards and I am completely discreet. If, for example, I bump into you on 58th Street, and you are going into the Paris Cinema, I will not acknowledge you and I will not talk to you. That would be breaking the rules. Yes. The rules.

There are seventeen rules altogether.

The most important one is that you do not touch me. I know I already said that, but it's worth repeating, don't you think? The second most important one is that you do not touch yourself. And the third most important rule is that you appear and remain completely dressed. You don't have to wear a suit or tie, but a nice sports coat and a pair of khakis or well-pressed chinos are appreciated. You may not eat during the session. This isn't actually on the list of rules, but it's common sense. Obviously it's hard to talk about sex when a man is chomping on a pastrami sandwich. And there's the smell to consider as well. It gets distracting. So no eating. However, you may drink. Cola, orange juice, bottled water, and beer or wine-in moderation-are all acceptable. No hard alcohol. It dulls the senses, and you just won't get your money's worth-not that I care, but you might. I provide none of these refreshments. It's up to you to keep them in the fridge, and if your hotel doesn't supply you with a fridge… Actually, if you're not staying in the kind of hotel that supplies you with a completely stocked fridge, then I probably won't be visiting you.

I will not accept any beverages, so please don't offer me any. However, if my throat becomes dry after talking for a time and I need a glass of water, I will get up and fetch it myself. You don't need to bother yourself; I will take care of getting it and work the interruption seamlessly into my conversation. You will not even notice a change in tone, so don't imagine that you can get an extra five minutes at the end for lost time. There will be no lost time.

Now, the "menu," as I call it, is extensive, updated weekly, and includes not only the classic favorites such as the man who gets caught in a rainstorm and must seek shelter at the home of three nubile teenaged girls who have been abandoned by their parents and are living in a woodshed on the side of a deserted highway in Minnesota but also five or six daily specials. For instance, on Fridays I might offer Catholic schoolgirls in plaid jumpers and knee socks who forgot to put on their underpants that day, playing hopscotch on the sidewalk in front of your enormous split-level house in Mamaroneck, eating pork chops on a Friday, when Father O'Leary comes along and must find a way to teach them a lesson and punish them. This one takes place in 1967 and it's a favorite with fifty-three-year-old Jewish men from Westchester County.

Of course the list is computerized, alphabetized, and on the Internet. I do have a website, and you can access me at www.hoteltalk.org. This does not mean I will respond to inquiries, and I seldom answer e-mail. But please feel free to send a message. Just don't expect an answer.

Rule number four. After I leave, you must never pretend you are very preoccupied and get on the phone as I've closed the door, only to jump up, stand by the door, and spy on me while I punch the elevator button for the lobby, and then quickly run out of your hotel room the moment the elevator doors close, race down the stairs, follow me out of the lobby, and then dart and dodge through traffic, almost getting run over, trailing close behind me until I get in a cab, and then grab a cab yourself and tell the driver to follow my cab, giving your driver a hundred-dollar bill to do so, all the while trying to restrain the enormous erection that has been forming in your trousers as you descend the streets, 51st, 50th, 49th, 48th, 47th, wondering where the hell I am going to get out, nervous it might be 42nd, relieved in Chelsea, then sweating again through Tribeca and Chinatown, getting stimulated, too, imagining that I live in a loft apartment on Walker and Lisbernard with a poet boyfriend who beats me, and that I am not at all the hardened businesswoman that I appear to be but instead a victim, bringing home my ill-gotten gains and handing them over to a drunken poet named Raoul who hasn't written a decent line of verse in the last twenty-five years and hasn't shaved since Friday. Whatever you do, do not get out of the cab and follow me up the five flights of stairs and stand in the doorway, watching as he grabs at the cash still hot from your own hands, presented to me only minutes before, having nestled in your pocket for an entire afternoon. And do not feel tenderness for me when Raoul screams at me that I am a whore, a bitch, and knocks me about the filthy kitchen, throwing pots and pans, as he continues to get drunker and rail against the New York literary scene, harping on the difference between the experimental poets and the language poets, and how the hell John Ashbery got to be so darn famous, when he suddenly lifts up my skirt, kisses my thighs, begs me for forgiveness as he pulls at my garter belt, brings me closer to him-me standing, while he sits at the kitchen table, wearing only boxers and a T-shirt with tomato sauce stains-rubbing my legs, pushing them apart, poking his fingers inside, deeper and deeper, while he talks about going to Tuscany to live for a year, renting a villa and maybe even having a baby and changing citizenship, while you stand there just outside the open door, and suddenly our eyes meet and you believe in that moment that you can rescue me. Then you watch as I close my eyes, and you are not sure whether I saw you or not, or whether I am thinking about Raoul. About how, despite the fact that he is a dreamer and we will always be stuck together in this godforsaken heat, with him pressing his dirty, unshaven face up against my soft chin, taking me there on the kitchen table, and me moaning as he forces his way in, as I concentrate on the knife on the counter and the beer bottle in the sink, while you stand outside the door, witness to all this, wondering if there are any sublets available in this roach-infested building and how you might leave your wife in Cincinnati for me.

Rule number five. You must never leave your wife for me. I know. This is a difficult one. More difficult than remaining dressed or not touching me. Right now you don't think it will be a problem, but you're wrong. This problem always crops up, primarily because you don't see it as a problem so you don't prepare for it, and then one day you find yourself cleaning out the attic, packing away photo albums, deleting names and addresses on your Rolodex and opening up a mailbox number at the Canal Street Post Office.

You're probably wondering how I got started doing what I do, and you're probably wondering exactly why I do it, and if there's any possibility that I do anything more-perhaps for a bit more money-than simply sit on your bed and talk. The answer is no. I do nothing more than sit on your bed and talk, and I am not going to tell you why I do what I do or if I have any plans to do more. But of course you might not care one iota whether I tell you what I do when I'm not here sitting on your bed. You may be the type who wants to tell me about what you do when I'm not sitting on your bed, you may be the type who wants to sit there for forty-five minutes and tell me all about your fantasies, how you really like the idea of you and two women together and how you like to imagine that I have a sister named Candy, who's still in high school even though she's nineteen and a half because she's been held back two years in a row as a result of an undiagnosed learning disability and a penchant for playing hooky. You may want to tell me how Candy's morals are skewed because she hasn't had much parental guidance and her father abused her, and that at fourteen she fell in love with Mr. Swann, her geometry teacher, and he began to explain an especially difficult proof one afternoon in the back of his eighth-grade classroom, and as it got to be about four o'clock and the room grew dimmer and dimmer, he noticed how Candy's delicate white ankles led up to a shapely calf, which led to a girlish knobby knee with a little flesh-colored Band-Aid pointing upward to Candy's supple thigh, which she crossed and uncrossed, and crossed and uncrossed, pressing her wool plaid skirt, the green and blue and yellow lines crisscrossing over and over again, creating a kind of geometrical pattern that rises and falls according to her breathing and the movement of her hands across her lap, and her hands across her lap, yes, resting right there, on top of her pubis, so soft and furry, you imagine that you-because you are now Mr. Swann, the geometry teacher, don't deny it-cannot help but lean forward and put your hand on top of Candy's and press it down, comforting her, saying, "There, there, now the Pythagorean theorem is not so very hard to grasp." And in that moment, your eyes meet and she leans forward, slowly closing her eyes, almost as if she has fallen asleep-suddenly decided to take a nap in the middle of your classroom, in the middle of the afternoon, because geometry is just so wearisome, and she falls into your arms, kissing you full on the mouth, and you, supporting her slender frame, kiss her back, and back, and back, and then her father walks into the room and says, "What the hell are you doing to my daughter?"

Hah! You didn't expect that, did you? I apologize, but I just couldn't help myself. Rule number seven-I have every right to start off telling a story about a menage a trois and then suddenly switch gears and tell a story about a geometry teacher getting brought up on sexual harassment charges and losing his job and being sent to prison, where all sorts of dreadful things happen, and if you'd like I'd be glad to tell you all about them in lurid detail. No extra charge for that.

Did I mention what rule number six is?

No? Oh, that's too bad.

Rule number six, then-you must never criticize anything I say or do. I think this bears repeating. You must never criticize anything I say or do. I know what I'm doing, and even if it seems like I've lost all control and I really should not be out talking about sex to strange men in hotel rooms, rather that I should be home in bed watching soap operas with all the doors and windows locked and a thick blanket wrapped around my body, and my psychotherapist's telephone number poised on redial, you must not say a word about it. You must behave as if everything is as it should be. Even if I were to suddenly begin sobbing in the middle of a story and tell you that someone in my family died this morning, someone quite close to me-my mother for instance. Even if I were to suddenly begin discussing how much I loved her and how I am completely lost without her, and how I am really psychopathically sad, and this whole sex-talk business is simply a reaction to a repressed childhood and an overbearing mother, and now that my mother has died I no longer feel the urgent need to rebel and I don't know why the hell I'm in your hotel room because it all seems so futile and idiotic, and just plain bad.

The main reason you are not allowed to criticize me is because I am extremely sensitive. I know I might not seem it, but the truth is, I am. It might seem unlikely to you that I go home and think about you and all my other clients, the millions of men I've seen in my many years of business, but in fact I do. I think about each and every one of you. I keep a file on you. I carry this file wherever I go. You probably want to know what I have in this file, but I'm not going to tell you. That would be breaking the rules. That's rule number nine, perhaps. I'm not sure. I'm losing track. But I will tell you a few of the things I keep on file about you. For instance, if you prefer domineering women, if you loved your mother too much, if you think all women are whores and that only your mother is truly good and pure and clean, and that if you keep yourself pure for her she will finally see your goodness and kiss you on your lips, take you to her bedroom-the one with all those pink woolen blankets and lace, and pictures of the children, the one with your father's ties hanging limply in the closet, smelling of the 9:07 p.m. train from Grand Central Station, the vanilla-scented bedroom where the secret of procreation is kept, the origins of your very own DNA, and there, there, finally knowing that you have been good, that you have saved that little corner of your brain, your heart, your soul for her alone, she will take you back to whence you came.

You see, I keep track of these things. Plus what's your favorite color, ice cream flavor. What your pet peeves are, whether you prefer blondes over brunettes, if you take cream in your coffee, if you've ever had a fantasy involving the laundromat and a millionaire businessman who walks in because he's lost, busy on his cell phone when he sees a young girl wearing only her underwear because that's all she's got and the rest of her clothes are in the dryer, and she lives in Santa Cruz, and you, movie mogul from Hollywood, think, wouldn't she be good in your next picture? So you eye her there, in the middle of the laundromat, sitting there on top of the vibrating Westinghouse Superspin in nothing but a pair of slightly tattered thong bikini underpants and a white lace bra that barely covers ample brown breasts straining to burst out of the thin latticework of fabric, and she smiles at you, whispering, "Hi, my name is Cherise. Would you like to know the ins and outs of doing your laundry here at the Suds and Gossip? Believe me, I know the ins and outs because I've been doing my laundry here since I was a little girl about seven years old, with my mom. She used to be this exotic dancer in San Francisco until she moved me and my three brothers and two sisters here to Santa Cruz. She said we'd have a healthier lifestyle, but now she's cut her hair, dyed it green, pierced her navel, and joined some weird religious cult."

You, movie mogul that you are, all the way from Hollywood, are not thinking about the Westinghouse or the spin cycles or the Fab with Fresh Lemon-Scented Borax, but instead you are concentrating on her thighs, so brown and firm, and her ass, perched there-just

You feel a little excited about that. The dog part. Don't be embarrassed. I know these things. It's my job. I'm a professional. I'm absolutely attuned to all the nuances and subtleties of my work. I'm completely intuitive and psychic. I read minds. I analyze handwriting. I know the zodiac. I know your sun sign, your moon sign, your rising sign. I know when Mercury is going retrograde, and when Jupiter is entering your sun sign, and how you become so sensitive whenever Uranus gets anywhere near Pisces.

I know what you had for breakfast this morning. I know when you've had too much sodium, when you should cut down on the caffeine. I know what you did in the bathroom of the lobby. I know what you called your mother's sister when you were twelve years old and didn't know better. I know you feel guilty about the day you called your father a big fat jerk. I know when your moon is out of phase. I know about the lie you told when you wanted to get out of that engagement. I know when you last saw your psychotherapist. I know about the thing you did on the side of the garage when you were eight and you thought no one could see. I saw you.

And I know when you haven't called for your weekly appointment because you're sitting in the corner of your kitchen, crouched between the refrigerator and the stove, wearing nothing but your Calvins, shivering and shaking. And I know about that week you did nothing but watch Hitchcock's

Rule number ten. You are not allowed to buy clothes exactly like mine and then go out and get a wig and walk around New York City as if you were me, buying flowers in Chelsea, a latte in the Village, and a coffee-table art book at Rizzoli's in Soho. You are not allowed to pretend you are me and you are having a nervous breakdown, a kind of

Rule number seventeen-I will not murder for you. I will not commit a crime for you. I will not die for you. I will not pay your bills, get you out of debt, steal a brand-new car for you, talk to your mother, get your twenty-three-year-old daughter to move out of your house, and I will not, absolutely not, poison your wife for you. So don't even ask me.

Now, you're probably growing a little discouraged, thinking, all these rules-where's the fun? What's the point? Why am I paying these kinds of prices to be with a woman-and not even a movie-star type, but an ordinary woman-if there are going to be all these rules?

Here is my answer to that: these are the rules. And there is no fun. So get the hell out if that's what you're after. Get out! Hello? I said get the hell out! Why are you still here? I know why. I know exactly why. Yes, I do. Come closer. I'll tell you why you're still here. It's because you've been bad.

And you know it. And I know it. Remember? I know everything about you. I even know you like to make a squeaky grunting sound when you're in the throes of orgasm. That only the thought of a small mouse nestled inside a chunk of Swiss cheese and the cat, Sylvester, poised atop the refrigerator with a cartoon anvil, waiting to drop it on the unsuspecting Tom and Jerry, will get you in the mood. That when you are rubbing yourself up against a woman, you are thinking about Chips Ahoy chocolate chip cookies and Bosco-flavored milk on a TV tray, about that afternoon in February when you stayed home from school sick as a dog and your mother leaned down to kiss your steaming forehead and you inhaled the fragrance of day-old Chanel No. 5 as your eyes were glued to

By the way, I've talked to your mother.

In fact, your mother is waiting outside the door for you, and she's got a big paddleboard and bottle of castor oil.

Just kidding. I mean, about the paddleboard and the castor oil. Not about talking to your mother because I did talk to your mother. Would you like to know what she said? Of course you would. She said: get on with it. Get over it. Grow up. She told me she's gone to Tahiti to live out the rest of her life among the natives, like Gauguin.

Now don't go and imagine your mother prancing naked among the palm fronds. That's called regression. No, instead imagine this-she's gone. She's happy. She's dancing among the orchids and lilies, wearing a nice little modest floral muumuu. She's drinking a daiquiri with a little paper parasol stuck in it. She's writing a novel. She's taking up singing. She's painting pictures. She's scuba diving. Collecting sea shells. Making pottery. Writing a screenplay. She's bought a video camera. Become a lounge singer. She's taken up with a hotel manager named Maurice. She's happy, laughing. And she's not thinking of you. She's forgotten all about you.

She's not watching you. Therefore, you are free. Free. Yes, free. You don't have to make love to a clone of yourself. You don't have to have sex with a rubber doll, a pinup girl, a cyberspace babe, a voice on the telephone, an Internet surfer girl, a dominatrix in leather lederhosen, a girl in a fancy apartment on East 92nd Street who only wants you for your money because that's all you have to give since your heart belongs to Mommy. You don't have to look for a woman who is so different from Mommy-a different race or religion or height or hair color- that looking into her eyes at night will not send you into Oedipal Shock Syndrome. You don't have to run the moment someone mentions marriage because marriage means Mommy and Mommy means death.

I know, you panic as soon as a woman is nice, as soon as she kisses your steaming forehead, as soon as she coos in your ear. You think of mice and cats with an anvil poised above their heads. You want to kill. You don't want to kill. Or you want to watch the Super Bowl for twenty-four hours or read a 1,500-page science fiction novel, or take your weed whacker out and mow down innocent dandelions, their little yellow heads severed and lying lifeless on the edge of your driveway waiting to be flushed down the sewer with one burst from your big, long garden hose.

I never orgasm. Don't ask me why because I'm not going to tell you. But it's good for business, don't you think? If I were in the middle of a story, talking about sex, and I suddenly found myself aroused (I do occasionally get excited, but I can control myself), but suppose I was overcome by excitement and threw myself down on the floor, ripped off my panties, spread my legs and began fingering myself, frantically searching, groping, trying to locate the button that releases all this pent-up emotion and passion, and I were to scream as the rivers crash through the barriers of my psyche and pour down through my head and breasts and legs and the center of my being as I writhe and moan for a full twenty minutes about how

My mother died this morning.

Did I mention that?

I said I wasn't going to reveal anything personal, but I thought you might like to know, since we're on the subject of mothers anyway. Everybody said to me, "Go to work-it'll take your mind off of it." So here I am. I loved my mother. I can imagine her in Tahiti right now. She taught me about sex. I probably have my professional life to thank her for.

I wish you had known her. I wish she had taught you about sex instead of me.

Kiss me.

Now.

Please. Kiss me.

I know it's against the rules. I know I said

That's right. Sing to me, and get me a drink. Make it hard- vodka on the rocks. And then, come here. And kiss me.

Oh, I'm sorry. Time's up.

Jamie Callan's work has been published in

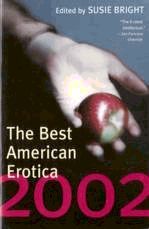

"Talk About Sex: An Orientation," by Jamie Callan, © 2000 by Jamie Callan, first appeared in

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |