"A Quiet Vendetta" - читать интересную книгу автора (Ellory R. J.)

ONE

Through mean streets, through smoky alleyways where the pungent smell of raw liquor hangs like the ghost of some long-gone summer; on past these battered frontages where plaster chips and twists of dirty paint in Mardi Gras colors lean out like broken teeth and fall leaves; passing the dregs of humanity who gather here and there amongst brown-papered bottles and steel-drum fires, serving to tap the vein of meager human prosperity where it spills, through good humor or diesel wine, onto the sidewalks of this district…

Chalmette, here within the boundaries of New Orleans.

The sound of this place: the jangled switching of interference, the hurried voices, the lilting piano, the radios, the street-walking, hip-dipping youths playing mesmeric rap.

If you listen, you can hear from porch or stoop the quarreling voices, innocence already bruised, challenged, insulted.

The clustered tenements and apartment blocks, pressed between streets and sidewalks like some secondary consideration, the unwanted reprise of an earlier discarded theme, and running like a strung-together, slipshod archipelago, hopping a block at a time out through Arabi, over the Chef Menteur Highway to Lake Pontchartrain where people seem to stop merely because the earth does.

Visitors perhaps wonder what makes this ripe, malodorous blend of smells and sounds and human rhythms as they pass over the Lake Borgne canal, over the Vieux Carre business district, over Ursuline’s and Tortorici’s Italian to Gravier Street. For here the sound of voices is strong, rich, vibrant, and there is motion spilling randomly, a pocket of curiosity gathered along the edge of a one-way street, a corridor of downward-sloping entries into parking lots beneath a tenement.

But for the squad car flashes, the alleyway is hot and thick with darkness. The tail-ends of cars – chrome fenders and liquid silk paintwork – catch the kaleidoscope flickers, and wide eyes flash cherry red to sapphire blue as police cars drive a wedge across the street and halt all passage.

To the left and right are hospitals, the Veterans’ and LSU Medical Center, and up ahead the South Claiborne Avenue Overpass, but here there is a splinter of activity through the network of arteries and veins that ordinarily flows uninhibited, and what is happening is unknown.

Patrolmen back the sensation-seekers away, herding them behind a hastily erected barrier, and once an arc lamp is hooked to the roof of a car, its beam wide enough to identify each and every vehicle pigeonholed in the alley, they begin to understand the source of this sudden police presence.

Somewhere a dog barks and, as if in echo, three or four more start up somewhere to the right. They holler in unison for reasons known only to themselves.

Third entrance from the Claiborne end a car is parked at an angle, its fender running a misplaced parallel to the others. Its positioning indicates speed, the rapid arrival and departure of its driver, or perhaps a driver who had not cared to harmonize with perspective and linear conformity, and though the carboy who walked this alleyway – minding automobiles, polishing brights and hoods for a quarter’s tip – has seen this car for three days consecutive, he hadn’t called the police until he’d looked inside. He’d taken a flashlight, a good one, and, pressing his face against the left rear quarterlight, he’d scanned the luxurious interior, minding he didn’t touch the white walls with his dirty, toe-peeping kickers. This wasn’t no ordinary car. There was something about it that had drawn him inside.

More people had gathered by then, and down a half a block or so some folks had opened up the doors and windows on a house party and the music was coming down with the smell of fried chicken and baked pecans, and when a plain Buick showed up and someone from the Medical Examiner’s office stepped out and walked towards the alleyway there were quite a few people down there: maybe twenty-five, maybe thirty.

And there was music – our human syncopations – as good tonight as any other.

The smell of chicken reminded the ME’s man of some place, some time he couldn’t remember now, and then it started raining in that lazy, tail-end-of-summer way that seemed to wet nothing down, the kind of way no-one had a mind to complain about.

It’d been a hot summer, a quiet kind of brutality, and everyone could remember how bad the smell got when the storm drains backed up in the last week of July, and how they spilled God-only-knew-what out into the gutters. It steamed, the flies came, and the kids got sick when they played down there. Heat blistered at ninety, tortured through ninety-five, and when a hundred sucked the air from parched lungs they called it a nightmare and stayed home from work to shower, to wrap split ice in a wet towel and lie on the floor with their cool hats pulled down over their eyes.

The Examiner man walked down. Early forties, name was Jim Emerson; he liked to collect baseball cards and watch Marx Brothers movies, but the rest of the time he crouched near dead bodies and tried to put two and two together. He looked as lazy as the rain, and you could sense in the way he moved that he knew he was unwelcome. He knew nothing about cars, but they’d run a sheet through come morning and they’d find – just like the carboy had figured – that this wasn’t no ordinary automobile.

Mercury Turnpike Cruiser, built by Ford as the XM in ’56, released commercially in ’57. V8, 290 horsepower at 4600 revs per minute, Merc-O-Matic transmission, 122-inch wheelbase, 4240 pounds in weight. This one was a hardtop, one of only sixteen thousand ever built, but the plates were Louisiana plates – and should have been on a ’69 Chrysler Valiant, last booked for a minor traffic violation in Brookhaven, Mississippi seven years before.

The carboy, released without charge within an hour and a half of his report, had stated emphatically that he’d seen blood on the back seat, a real mess of it all dried up on the leatherwork, clotted in the seams, spilled over the edge of the seats and down on the floor. Looked like a sucking pig had been gutted in there. The Cruiser wore a lot of glass, its retractable rear window, quarter-lights and sides designed to permit full enjoyment of the wide new vistas open to turnpike travellers. Gave the boy a good look at the innards of this thing, because that’s what he’d figured was in there, and he wasn’t so far from right.

These were the Chalmette and Arabi districts, edge of the French business quarter, New Orleans City, state of Louisiana.

This was a humid August Saturday night, and only later did they clear the sidewalks, haul out that car and lever the trunk.

Assistant Medical Examiner Emerson was there to see a can of worms opened right up, and even the cop who stood beside him – hard-bitten and weatherworn though he was – even he took a raincheck on dinner.

So they levered the trunk, and inside they found some guy, couldn’t have been much more than fifty years of age, and Emerson told anyone who’d listen that he’d been there for three, perhaps four days. Car had been there for three if the boy’s observation was correct, and there were sections of the trunk’s interior, bare metal strips, where the man’s skin had adhered in the heat. Emerson had one hell of a job; eventually he decided to freeze the metal strips with some kind of spray and then peeled the skin away with a paint scraper. The trunk vic looked like mystery meat, smelled worse, and the autopsy report would read like an auto smash.

Severe cerebral hemorrhaging; puncture of temporal, sphenoid and mastoid; rupture of pineal gland, thalamus, pituitary gland and pons by standard dimension claw hammer (generic branding, available at any good hardware outlet for between $9.99 and $12.99 depending on which side of town you shopped); heart severed at inferior vena cava through right and left ventricle at base; severed at subclavian veins and arteries, jugular, carotid and pulmonary. Seventy percent minimum blood loss. Bruising to abdomen and coeliac plexus. Lesions to arms, legs, face, hands, shoulders. Rope burns and adhesive marks from duct tape to wrists, left and right. Rope fibers attached to adhesive identified beneath an infrared spectraphotometer as standard nylon type, again available from any good hardware outlet. Estimated time of death Wednesday 20 August, somewhere between ten p.m. and midnight, courtesy of New Orleans District 14 County Coroner’s Office, signed this day… witness… etc, etc.

The vic had been beaten six ways to Christmas. Tied at the wrists and ankles with regular mercantile and hardware nylon rope, beaten about the head and neck with a regular mercantile and hardware claw hammer, eviscerated, his heart cut away but left inside the chest cavity, wrapped in a regular sixty percent polyester, thirty-five percent cotton, five percent viscose bed-sheet, dumped in the back seat of a ’57 Mercury Turnpike Cruiser, driven to Gravier Street, moved to the trunk and then left for approximately three days prior to discovery.

There were interns to see to the arrival of the body at the Medical Examiner’s office, to watch over it for the couple of hours before it was moved to the County Coroner for full autopsy. Fresh-faced they were, young, and yet already beginning to get that world-weary edge of madness in their eyes, the kind of look that came from spending your life moving the dead from the scene of their misfortunes. They kept thinking

The Crime Scene Security Officer was the man who stood sentinel over the dead to ensure this mortality was not violated further, that no-one would walk through the spilled blood, no-one would move the torn clothing, the fibers, the fragments, that no-one would touch the weapon, the footprint, the microscopic smudge of vari-colored mud that could isolate the one thread that would unravel everything; selfishly, with some sense of internal hunger, he would clutch these images and visions to his chest. Like a child protecting a cookie jar, or candies, or threatened innocence, he sought to make permanent the very impermanent, and in such a way lose sight of the real truth of the matter.

But that would be tomorrow, and tomorrow would be another day altogether.

And by the time darkness edged its cautious way towards morning the people who had crowded the sidewalks had forgotten the story, forgotten perhaps why they went down there in the first place, because here – here, of all places in the world – there were better things to think of: jazz festivals in Louis Armstrong Park, the procession from Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, St Jude Shrine, a fire out on Crozat by Hawthorne Hall above the Saenger Theater that took the lives of six, orphaned some little kids, and killed a fireman called Robert DeAndre who once kissed a girl with a spider tattooed on her breast. New Orleans, home of the Mardi Gras, of little lives, unknown names. Stand. Close your eyes now and inhale this mighty sweating city in one breath. Smell the ammoniac taint of the Medical Center; smell the heat of rare ribs scorching in oiled flames, the flowers, the clam chowder, the pecan pie, the bay leaf and oregano and court bouillon and carbonara from Tortorici’s, the gasoline, the moonshine, the diesel wine: the collected perfumes of a thousand million intersecting lives, and then each life intersecting yet another like six degrees of separation, a thousand million beating hearts, all here, beneath the roof of the same sky where the stars are like dark eyes that see everything. See and remember…

The image evaporates, as transient as steam through subway grilles or from blackened copper funnels projecting from the back walls of Creole restaurants, steam rising from the floor of the city as it sweltered through the night.

Like steam from the brow of a killer as he’d worked his heart out…

Sunday. A hard, bright day. The heat had lifted as if to make room to breathe. Children were stripped to the waist, gathered at the corner of Carroll and Perdido and spraying each other with water from rubber snaking hoses that traipsed from the porches of clapboard houses set back from the street, behind low banks of hickory and water oaks. Their squeals, perhaps more from relief than excitement, scattered like streamers through the low, heady atmosphere. These sounds, of life in its infancy, were there as John Verlaine was woken by the incessant shrilling of the phone; and such a call at that time in the morning meant, more often than not, that someone somewhere was dead.

New Orleans Police Department for eleven years, somewhere in amongst that three and a half years in Vice, the last two years in Homicide; single, mentally sound but emotionally unstable; most often tired, less often smiling.

Dressed quickly. Didn’t shave, didn’t shower. More than likely there’d be a mess of shit to wade through. You got used to it. Perhaps you

Heat had been angry the past few days. Closed you up inside it like a fist. Hard to breathe. Sunday morning was cooler; the air lightened a little, the feeling that pressured storm clouds could break through everything now dissipated.

Verlaine drove slowly. Whoever had died was already dead. No point in rushing.

He felt it would rain again, that lazy, tail-end-of-summer rain that no-one took a mind to complain about, but it would come later, perhaps during the night. Perhaps while he slept. If he slept…

Away from his apartment on Carroll, heading a straight north towards South Loyola Avenue. The streets seemed vacant but for a thin scattering of humanity’s lost, and he watched them, their tentative advances, their laughing faces, their hungover redness that spread from the doorways of bars out onto the sidewalk and into the street.

He drove without thought, and somewhere near the De Montluzin Building he hung a right, and then past Loew’s State Theater. Twenty minutes, and he stood at the Loyola end of Gravier. Down here there were mimosas and hickory trees, the branches chased of bark, the remnants of their pecan yield stolen weeks before by grimy thieving hands.

Verlaine looked away leftwards, away from Gravier, through the wisteria that had clung to the walls along this street since he could remember, their pendent racemes like clusters of grape hanging purple and delicate and sweet with perfume; past the grove of mimosas, their cylindrical heads like little spikes of color through the burgeoning light, out towards Dumaine and North Claiborne, the hum of traffic just another voice in this start-of-day humidity. Down among the water oaks and honey locusts, you could hear the cicadas challenging the distant sound of children who ran and played their catch-as-catch-can games on the sidewalks through air that sat tight like a drum, like it was waiting to be breathed.

He knew where the car had been, it was evident by its absence, and strung around the missing-tooth gap were crime scene tapes fluttering in the breeze. The body was found here, some guy beaten to death with a hammer. Ops told him as much as they knew on the phone, said he should go down there and see what he could see, and once he was done he should drive over to the ME’s office and speak to Emerson, check the scene report, and then on to the County Coroner to attend the autopsy. So he looked, and he saw what he could see, and he took some shots with his camera, and he walked around the edges of the thing until he felt he’d had enough and returned to his car. He sat in the passenger side with the door open and he smoked a cigarette.

Forty minutes later, the Medical Examiner’s office on South Liberty and Cleveland, back of the Medical Center. The day had grown in stature, promised a clear azure sky before lunch was over, promised a mid-afternoon in the late eighties.

Verlaine felt his head stretching as he walked from the car, trying to stay close to the store frontages beneath the awnings and out of the sun. His shirt was glued to his back beneath a too-heavy cotton suit, his feet sweated inside his shoes, his ankles itched.

Jim Emerson, youthful despite entering his early forties, Assistant Medical Examiner and very good at it. Emerson added a certain flair and insight to what would ordinarily have been a dry and factual task. He was sensitive to people, sensitive even when they were rigored and bloated and shattered and dead.

Verlaine stood in the corridor outside Emerson’s office for a moment.

Emerson rose from his desk and reached out his hand. ‘Short time, plenty see,’ he said, and smiled. ‘You up for the trunk job?’

Verlaine nodded. ‘Seems that way.’

‘Nasty shit,’ Emerson said, and glanced to the desk. Ahead of him were three or four pages of detailed notations on a yellow legal pad.

‘A surgeon we have here,’ he went on. ‘A real surgeon.’ He looked back at Verlaine, smiled again, nodded his head back and forth in a manner that was neither a yes nor a no. He reached into his coat pocket, took out a packet of bad-smelling Mexican cigarettes and lit one.

‘You looked at the body yet?’ he asked Verlaine. ‘We sent it over to the coroner a couple of hours ago.’

Verlaine shook his head. ‘I’m going there in a little while.’

Emerson nodded matter-of-factly. ‘Well, sure as shit it’ll spoil your Sunday lunch.’ He returned to sit at his desk and looked over his own notes. ‘It’s interesting.’

‘How so?’

Emerson shrugged. ‘The car maybe. The thing with the heart.’

‘The car?’

‘A ’57 Mercury Turnpike Cruiser. That’s over at one of the lock-ups. Helluva car.’

‘And the vic was in the trunk, right?’

‘What was left of him, yes.’

‘They got an ID?’ Verlaine asked.

Emerson shook his head. ‘That’s your territory.’

‘So what can you tell me?’ Verlaine reached for a chair against the wall, dragged it close to the desk and sat down.

‘Guy got the living hell knocked out of him. Smashed him up with a hammer and cut his freakin’ heart out… like the betrayal thing, right?’

‘That’s just rumor. That’s a rumor based on one case back in ’68.’

‘One case?’

‘Ricki Dvore. You know about that one?’

Emerson shook his head.

‘Ricki Dvore was a hustler, a druggist, a pimp, everything. He shipped liquor back and forth out of Orleans with his own trucks, stuff that was stilled someplace out beyond St Bernard… place has grown since then though. You know Evangeline, down south along Lake Borgne?’

Emerson nodded.

‘Stilled the stuff down there and brought it in in trucks, regular-looking artics with tanks inside the bodies. He gypped some dealer, someone from one of those crazy families down there, and one by one his wife, his kids, his cousins, they were all beaten on somehow. Three-year-old daughter lost a finger. They sent it to Dvore and he just kept on screwing up. Eventually they dragged him from his truck one night, cut his heart out and sent it to his wife. Cops had Christ knows how many people answering up for that, more crank calls, more confessions than anything I’ve ever heard of. They didn’t have a hope; case folded within a fortnight and stayed that way. They never found Dvore’s body – weighted down and sunk in a bayou someplace I’m sure. They just had his heart. That’s where the whole thing about betrayal and cutting out people’s hearts came from. It’s just a story.’

‘Well, whoever the hell did this, he left the heart inside the chest.’

‘Seems to me we go with the car,’ Verlaine said. ‘The car is good, strong. Maybe it’s a red herring, something so out of character it’s designed to throw the whole pitch of the invest, but it’s such a big part I somehow doubt it. Someone wants to throw the course they do something small, something at the scene, some minor fact that’s so minor only an expert would recognize it. The guys who do that kind of thing are smart enough to realize that the people after them are just as smart as they are.’

Emerson nodded. ‘You go down to the coroner’s office and take a look yourself. I’ll get this typed up and file it.’

Verlaine rose from the chair. He set it back against the wall.

He shook Emerson’s hand and turned to leave.

‘Keep me posted on this,’ Emerson said as an afterthought.

Verlaine turned back, nodded. ‘I’ll send you an e-mail.’

‘Wiseass.’

Verlaine pushed through the door and made his way down the corridor.

Heat had risen outside. Sweated on the way to his car, maybe a pint a yard.

County Coroner Michael Cipliano, fifty-three years old, an irascible and weatherworn veteran. Now only Italian by name, his father from the north, Piacenze, Cremona perhaps – even he’d forgotten. Cipliano’s eyes were like small black coals burning out of the smooth surface of his face. Gave no shit, expected none in return.

The humid, tight atmosphere that clung to the walls of the coroner’s theater defied the air-conditioning and pressed relentlessly in from all sides. Verlaine stepped through the rubber swing doors and nodded silently at Cipliano. Cipliano nodded back. He was hosing down slabs, the sound of the water hitting the metal surface of the autopsy tables almost deafening within the confines of the theater.

Cipliano finished the last table nearest the wall and shut off the hose.

‘You here for the heartless one?’

Verlaine nodded again.

‘Printed him for you I did, like the blessed patron saint that I am. Paper’s over there.’ He nodded at a stainless steel desk towards the back of the room. ‘Gopher’s sick. Took off day before yesterday, figured he picked something up from one of those John Does over there.’ Cipliano nodded over his shoulder to a pair of cadavers, floaters from all visible indications, the grey-blue tinge of the flesh, the swollen fingers and toes.

‘Found ’em Thursday face down in Bayou Bienvenue. Users both of them, tracks like pepper up and down their arms, in the groin, between the toes, backs of the knees. Gopher figures there’s cholera or somesuch in the Bayou. These cats roll in here with it and he contracts. Full of shit, really so full of shit.’

Cipliano laughed hoarsely and shook his head.

‘So what we got?’ Verlaine asked as he walked towards the nearest table. The smell was strong, rank and fetid, and even though he breathed through his mouth he could almost taste it. God only knew what he was inhaling.

‘What we got is a fucking mess and then some,’ Cipliano said. ‘If my mother only knew where I was on a Sunday morning she’d roll over Beethoven right there in her grave.’ The lack of reciprocal love between Cipliano and his five-years-dead mother was legend to anyone who knew him. Rumor had it that Cipliano had performed her autopsy himself, just to make sure, to make

‘Aperitifs and hors d’oeuvres are done, but at least you arrived in time for the main course,’ Cipliano stated. ‘Whoever did your John Doe here knew a little something about surgery. It ain’t easy to do that, take the heart right out clean like that. It wasn’t no pro job, but there’s one helluva lot of veins and arteries connecting that organ, and some of them are the thickness of your thumb. Messy shit, and really quite unusual if I say so myself.’

The skin of the corpse was gray, the face distorted and swollen with the heat it must have suffered locked in the trunk of the car. The chest revealed the incisions Cipliano had already made, the hollowness within that had once held the heart. The stomach was bloated, the heap of clothes bloodstained, hair like clumps of matted grass.

‘A clean-edged knife,’ Cipliano stated. ‘Something like a straight razor but without the flat end, here and here through the left and right ventricles at the base, and here… here across the carotid we have a little chafing, a little friction burn where the blade did not immediately pass through the tissue. Subclavian incisions and dissections are clean and straight, swift cuts, quite precise. Perhaps a scalpel was used, or something fashioned to the accuracy of a scalpel.’

‘Was the whole thing done in one go, or was there time between opening up the chest and severing the heart?’ Verlaine asked.

‘All in one go. Tied him up, beat his head in, opened him up like a jiffy bag, severed some of the organs to get to the heart. The heart was cut out, replaced inside the chest. The vic was already lying on the sheet, it was wrapped over him, dumped in the car, driven from wherever, and transferred to the trunk, abandoned.’

‘Lickety-split,’ Verlaine said.

‘Like the proverbial hare,’ Cipliano replied.

‘How long would something like that take, the whole operation thing?’

‘Depends. From his accuracy, the fact it was obvious he had some idea of what he was doing, maybe twenty minutes, thirty at best.’

Verlaine nodded.

‘Seems the body was moved, tilted upwards a couple of times, maybe even propped against something. Blood has laked in different places. Struck with the hammer maybe thirty or forty times, some of the blows direct, others glancing towards the front of the head. Tied initially, and once he was dead he was untied.’

‘Fingerprints on the body?’ Verlaine asked.

‘Need to do an iodine gun and silver transfers to be sure, but from what I can tell there seem to be plenty of rubber smudges. He wore surgical gloves, I’m pretty sure of that.’

‘Can we do helium-cadmium?’

Cipliano nodded. ‘Sure we can.’

Verlaine helped prepare. They scanned the limbs, pressure points, around each incision, the gray-purple flesh a dull black beneath the ambient light. The smears from the gloves showed up as glowing smudges similar to perspiration stains. Where the knife had scratched the surface of the skin there were fine black needle-point streaks. Verlaine helped to roll the body onto its front, a folded body bag tucked into the chest cavity to limit spillage. The back showed nothing of significance, but Verlaine – bringing his line of vision down horizontally with the surface of the skin – noticed some fine and slightly lustrous smears on the skin.

‘Ultra-violet?’ he asked.

Cipliano wheeled a standard across the linoleum floor, plugged it in and switched it on.

The coal black eyes squinted hard. ‘Shee-it and Jesus Christ in a gunny sack,’ he hissed.

Verlaine reached towards the skin, perhaps to touch, to sense what was there. Cipliano’s hand closed firmly around his wrist and restrained the motion.

A pattern, a series of joined lines glowing whitish-blue against the colorless skin, drawn carefully from shoulder to shoulder, down the spine, beneath the neck and over the shoulders. It glowed, really glowed, like something alive, something that possessed an energy all its own.

‘What the fuck is that for Christ’s sake?’ Verlaine asked.

‘Get the camera,’ Cipliano said quietly, as if here he had found something that he did not wish to disturb with the sound of his voice.

Verlaine nodded, fetched the camera from the rack of shelves at the back of the room. Cipliano took a chair, placed it beside the table and stood on it. He angled the camera horizontally as best he could and took several photographs of the body. He came down from the chair and took several more shots across the shoulders and the spine.

‘Can we test it?’ Verlaine asked once he was done.

‘It’s fading,’ Cipliano said quietly, and with that he took several items from a field kit, swabs and analysis strips, and then with a scalpel he removed a hair’s-width layer of skin from the upper right shoulder and placed it between two microscope slides.

Less than fifteen minutes, Cipliano turning with a half-smile tugging at the corners of his mouth. ‘Formula C2H24N2O2. Quinine, or quinine sulphate to be precise. Fluoresces under ultraviolet, glows whitish-blue. Only other things I know of that do that are petroleum jelly smeared on paper and some kinds of detergent powder. But this, this is most definitely quinine.’

‘Like for malaria, right?’ Verlaine asked.

‘That’s the shit. Much of it’s been replaced with chloroquinine, other synthetics. Take too much and it gives you something called cinchoism, makes your ears ring, blurs your vision, stuff like that. Lot of guys from out of Korea and ’Nam took the stuff. Most times comes in bright yellow tablets, can come in a solution of quinine sulphate which is what we have here. Used sometimes as a febrifuge-’

‘A what?’

‘Febrifuge, something to knock out a fever.’ Verlaine shook his head. His eyes were fixed on the faint lines drawn across the dead man’s back. Glowed like St Elmo’s fire, the

‘I’ll get the pictures processed. We’ll have more of an idea of what the configuration means.’

That word – configuration – stuck in Verlaine’s thoughts for as long as he remained at the County Coroner’s office, sometime beyond that if truth be known.

Verlaine watched as Cipliano picked the body to pieces, searching for grains, threads, hairs, taking samples of dried blood from each injured area. There were two types, the vic’s A positive, the other presumably the killer’s, AB negative.

The hairs belonged to the dead guy, no others present, and scraping beneath the fingernails Cipliano found the same two types of blood, a skin sample that proved too decayed to be tested effectively, and a grain of burgundy paint that matched the car.

Verlaine left then, took with him the print transfers Cipliano had made, asked him to call when the pictures were processed. Cipliano bade him farewell and Verlaine passed out through the swing doors into the brightly-lit corridor.

Outside the air was thick and tainted with the promise of storm, the sun hunkered down behind brooding clouds. The heat breathed through everything, turned the surface of the hot top to molasses, and Verlaine stopped to buy a bottle of mineral water from a store on the way back to his car.

There was something present today, something in the atmosphere, and breathing it he felt invaded, even perhaps abused. He sat in his car for a while and smoked a cigarette. He decided to drive back to the Precinct House and wait there for Cipliano’s call.

The call came within an hour of his arrival. He left quickly, as inconspicuously as he could, and drove back across town to the coroner’s office.

‘Have a make on the pattern,’ Cipliano stated as Verlaine once again entered the autopsy theater.

‘It appears to be a solar configuration, a constellation, a little crude but it’s the only thing the computer can get a fix on. It matches well enough, and from the angle it was drawn it would be very close to what you’d see during the winter months from this end of the country. Maybe that holds some significance for you…’

Cipliano indicated the computer screen to his right and Verlaine walked towards it.

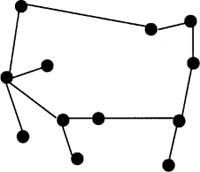

‘The constellation is called Gemini, but this pattern contains all twelve major and minor stars. Gemini is the two-faced sign, the twins. Mean anything to you?’

Verlaine shook his head. He stared at the pattern presented on the screen.

|

‘So, you get anything on the prints?’ Cipliano asked.

‘Haven’t put them through the system yet.’

‘You can do that today?’

‘Sure I can.’

‘You got me all interested in this one,’ Cipliano said. ‘Let me know what you find, okay?’

Verlaine nodded, walked back the way he’d come, drove across once more to the crime scene at the end of Gravier.

The alleyway was silent and thick with shadows, somehow cool. As he moved, those self-same shadows appeared to move with him, turning their shadow-faces, their shadow-eyes towards him. He felt isolated, and yet somehow not alone.

He stood where the Mercury had been parked, where the killer had pulled into the bay, turned the engine off, heard the cooling clicks of the motor; where he’d perhaps smiled, exhaled, maybe paused to smoke a cigarette before he left. Job done.

Verlaine shuddered and, stepping away from the sidewalk, he moved slowly to the wall that only days before had guarded the side of the Cruiser from view.

He left quickly. It was close to noon. Sunday, the best day perhaps to find a space in the schedule to get the prints checked against the database. Verlaine figured to leave the transfers with Criminalistics and go check out the Cruiser at the pound. He logged the request, left the transfers in an envelope at the desk, scribbled a note for the duty sergeant and left it pinned to his office door just in case they came looking for him.

It was gone lunchtime and Verlaine hadn’t yet eaten a thing. He stopped at a deli en route, bought a sandwich and a bottle of root beer. He ate while he drove, more out of necessity than any other consideration.

Twenty minutes later: New Orleans Police Department Vehicle Requisition Compound, corner of Treme and Iberville.

John Verlaine stood with the criss-crossed shadows of the wire mesh fence sectioning his face into squares, and waited patiently. The officer within, name of Jorge D’Addario, had stated emphatically that until he received something official, something

He walked between the rows of symmetrically parked cars, took a wide berth on a boiler-suited black-faced man chasing a fine blue line through the chassis of a Trans Am with an oxyacetylene torch. Copper-colored sparks jetted like Independence Day fireworks from the needle-point flame. Down a half dozen, right, and through another alleyway of vehicles – a Camaro S/Six, a Berlinetta, a Mustang 351 Cleveland backed up against a Ford F250 XLT, and to his left before the Cruiser a GMC Jimmy with half the roof torn away, giving the impression of a can of peas opened up with a pneumatic drill.

Verlaine paused, stood there ahead of the Mercury Turnpike, the yards of burnished chrome, the mirrored wheel shell standing out from the trunk, the indents and dual fresh-air vents, the double tail fins and burgundy paintwork. Sure as shit wasn’t no ordinary car. He stepped forward, touched the edged concave runners that swept from the tail to the quarterlights, leaned to look along the base of the vehicle, its white-wall tires muddied a little beneath the chrome underslung chassis and overlapping arches. Requisition Compound wasn’t the place for such a car as this.

Moving to the rear of the vehicle, Verlaine took a pair of surgical gloves from his pockets. He snapped them on and lifted the trunk. The night before, a dead guy had been found in there; now it smelled like formaldehyde, like something antiseptic tainted with decay. The image of the body he’d stood over in the autopsy theater crammed into this space was as clear as ever. His stomach turned. He felt the root beer repeating on him like cheap aniseed mouthwash.

He went back and fetched his camera from his car. Took some snaps. Looked inside the back of the Cruiser, saw the thick lake of dried blood across the leatherwork and down onto the carpet. Took some shots of that. Finished the film and rewound it.

Fifteen minutes and he was walking his way out of the compound; paused to sign the visitation docket in D’Addario’s kiosk at the gate, turned his car off Iberville and headed back to the Precinct House to check the status of the fingerprint search.

Verlaine, perhaps for no other reason than to kill a little time, took the long route. Back of the French business quarter, along North Claiborne on St Louis and Basin. Here was Faubourg Treme, city of the dead. There were two cemeteries, both of them called St Louis, but the one in the French Quarter was the oldest, the first and original burial ground dating back to 1796. Here were the dead of New Orleans – the whites, the blacks, the Creoles, the French, the Spanish, the free – because they all wound up here, every sad and sorry one of them. Death held no prejudice, it seemed. The graves did not reveal their color, their dreams, their fears, their hopes; gave merely their names, when they arrived and when they departed. Crosses of St Augustine, St Jude, St Francis of Assisi, patron saint of travelers who loved nature, who founded the Franciscans, who begged for his meals and died a pauper. And on the other side were the believers, the gris-gris crosses marking their passage into the underworld. Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau, R.I.P. Haitian cathedrals of the soul.

He reached Barrera at Canal by the Trade Mart Observation Tower, asked himself why he was driving so far out of his way, shrugged the question away. He was now ahead of the French Market beyond Vieux Carre Riverview. A good couple of miles of warehouses interspersed with clam joints, jazz clubs, bars, restaurants, diners, sex shops, a movie theater and the landing jetties for the many harbor tours. Despite the heat the streets down there were busy. Groups of Creoles and blacks stood aimlessly at corners and intersections, hurling arrogant and playful remarks at passing women, flying the finger at compadres and amigos, drinking, laughing, talking big, oh so very big, in this smallness of life. Daily you could find them, nothing better to do, persuading themselves that this was the good life, the life to live, where things were easy come easy go, where everyone who wasn’t there was a jerkoff, a dumbjohn, a turkey; where the duchesses sailed by, their hands on the arms of trade, making their way to some seedy Maison Joie down the street and back of the next block, and these corner-hugging, street-smart hopefuls were wise to their act and knew not to say anything whatever the trade looked like, for a duchess with a stiletto heel to your throat was no cool scene. Here, the air was haunted forever with the smell of fish, of sweat, of cheap cigar smoke passing itself off as hand-rolled Partageses; here existence seemed to roll itself out endlessly from one dark and humid dream to the next, with no change to spare but daylight in between. Daylight was for scoring, for counting money, for sleeping some, for drinking a little to prep the tongue for the onslaught that would come later. Daylight was something God made so life was not one endless party; something, perhaps, to give the neon tube signs a rest. Places such as this they held cock fights; places such as this the police let them. In the guidebooks it suggested you visit these parts only in groups, directed by an official, never alone.

Verlaine crossed the junction of Jackson and Tchoupitoulas where the bridge spanned the river and joined 23, where 23 crossed the West Bank Expressway, where the world seemed to end and yet somehow begin again with different colors, different sounds, different senses.

He arrived unnoticed at the Precinct House – the place was almost deserted – and checked status on the prints. They had nothing yet, perhaps wouldn’t until someone pulled their finger out Monday morning and got the hell on with what they were paid to do.

It was gone five, the afternoon tailing away into a cooler early evening, and for a little while Verlaine sat at the desk in his office looking out southwards to the Federal Courts and Office complex back of Lafayette Square. Beneath him the street slowly emptied of traffic, and then filled once more with the hubbub of pedestrians making their slow-motion way to Maylies Restaurant, over to Le Pavilion, life traveling onwards in its own curious and inimitable way. A man had been butchered, a brutal and sadistic termination, his savaged corpse parked in a beautiful car in an alleyway down off of Gravier. They were all fascinated, horrified, disgusted, and yet each of them could turn and walk away, take dinner, see the theater, meet their friends and talk of small inconsequentialities that possessed their attention to a far greater degree. And then there were others, among whom Verlaine counted himself and Emerson and Cipliano, perhaps themselves as crazy as the perpetrators, given that their involvement in life was limited to tracing and finding and sharing their breath with these people – the sick, the demented, the sociopathic, the disturbed. Someone somewhere had taken a man, hammered in his head, bound his hands behind his back, opened his chest, cut away his heart, driven him into town and left him. Alone. That someone was somewhere, perhaps avoiding eyes, avoiding confrontations; perhaps hiding somewhere in the bayous and everglades, out past the limits of Chalmette and the Gulf Outlet Canal where the law walked carefully, if at all.

Verlaine, already weary, took a legal pad, balanced it across his knee and jotted down what he knew. The time of death, a few facts regarding the condition of the vic, the name of the car. He drew the constellation of Gemini as best as he could recall, and then stared at it for some time, thinking nothing very much at all. He left the pad there on the desk and called it a day. He drove home. He watched TV for a little while. Then he rose and showered, and when he was done he sat in a chair by the window of his bedroom dressed in a robe.

The warmth of the day, the way his mind had been stretched by its events, took its toll. A little after ten Verlaine lay on his bed. He drifted for a while, the window wide, the sounds and smells of New Orleans drifting back into the room with the faintest of breezes.

You had to live here to understand, you had to stand there in Lafayette, out in Toulouse Wharf, there in the French Market as you were jostled and shoved aside, as the ripe odor of humanity and the rich sounds of its brutal rhythms swarmed right through you…

You had to do these things to understand. This was the Big Easy, the Big Heartacher. New Orleans, where they buried the dead overground, where the guidebooks recommended you walk in groups, where everything slid over-easy, sunny-side down, where the Big George fell on eagles nine times out of ten.

This was the heart of it, the American Dream, and dreams never really changed, they just became faded and forgotten in the manic slow-motion slide of time.

Sometimes, out there, it was easier to choke than to breathe.

| © 2025 Библиотека RealLib.org (support [a t] reallib.org) |